Edward II of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Edward II |

|

|---|---|

Effigy in Gloucester Cathedral

|

|

| King of England (more ...) | |

| Reign | 7 July 1307 – 13/25 January 1327 |

| Coronation | 25 February 1308 |

| Predecessor | Edward I |

| Successor | Edward III |

| Born | 25 April 1284 Caernarfon Castle, Gwynedd, Wales |

| Died | 21 September 1327 (aged 43) Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, England |

| Burial | 20 December 1327 Gloucester Cathedral, Gloucestershire, England |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail |

|

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Edward I, King of England |

| Mother | Eleanor, Countess of Ponthieu |

Edward II (born 25 April 1284 – died 21 September 1327) was the King of England from 1307 until he was removed from power in January 1327. He was also known as Edward of Caernarfon. Edward was the fourth son of King Edward I. He became the heir to the throne after his older brother, Alphonso, passed away.

Edward joined his father on military trips to Scotland starting in 1300. In 1307, he became a knight in a special ceremony at Westminster Abbey. He became king later that year when his father died. In 1308, he married Isabella of France, the daughter of the powerful King Philip IV. This marriage was meant to help solve problems between England and France.

Edward had a very close friendship with Piers Gaveston. Gaveston's power and proud attitude upset many important nobles, called barons, and the French royal family. Edward was forced to send Gaveston away. When Gaveston returned, the barons made the King agree to big changes called the Ordinances of 1311. The barons then sent Gaveston away again. Edward brought him back, which made the barons angry.

In 1312, a group of barons, led by Edward's cousin, the Earl of Lancaster, captured and executed Gaveston. This started many years of fighting. English forces struggled in Scotland. Edward was badly beaten by Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. A huge famine followed, and people started to criticize the King's rule more and more.

The Despenser family, especially Hugh Despenser the Younger, became Edward's close friends and advisors. In 1321, Lancaster and many barons took the Despensers' lands. They forced the King to send them away. Edward then led a military campaign, capturing and executing Lancaster. Edward and the Despensers became very powerful. They undid the 1311 reforms, punished their enemies, and took their lands.

Edward could not win in Scotland, so he signed a truce with Robert the Bruce. Opposition to Edward's rule grew. In 1325, Isabella was sent to France to make a peace treaty. She turned against Edward and refused to come back. Isabella joined forces with Roger Mortimer, a baron who had been exiled. In 1326, they invaded England with a small army. Edward's government fell apart. He fled to Wales, where he was captured in November. Edward was forced to give up his crown in January 1327 to his son, Edward III. He died in Berkeley Castle on 21 September. Many historians believe he was murdered by those who now ruled.

Edward's story has inspired many works, including plays, films, and books. People at the time criticized Edward for his failures in Scotland and his harsh rule later on. However, some later historians noted that parliamentary institutions grew stronger during his reign. This was seen as a good thing for England in the long run. Historians still debate whether Edward was a lazy and bad king, or simply a ruler who struggled and failed.

Contents

Early Life and Family (1284–1307)

Birth and Childhood in Wales

Edward II was born at Caernarfon Castle in north Wales on 25 April 1284. This was less than a year after his father, Edward I, had conquered the area. Because of this, Edward II is sometimes called Edward of Caernarfon. The king likely chose this castle for his son's birth on purpose. It was an important place for the Welsh people. It was also the center of the new royal government in North Wales.

Edward's birth led to predictions of great things. Some people thought he would be like a new King Arthur. They believed he would lead England to glory. A writer in the 1500s said the baby was offered to the Welsh as a prince "that was borne in Wales and could speake never a word of English". But there is no proof this story is true.

Edward's name was English. It connected him to the Anglo-Saxon saint Edward the Confessor. His father chose this name instead of more common French or Spanish names. Edward's older brothers, John, Henry, and Alphonso, had all died before him. Alphonso died in August 1284, making Edward the heir to the throne. Edward was a healthy child. But people worried he might also die, leaving his father without a male heir.

Edward was cared for by a wet nurse named Mariota or Mary Maunsel. Later, Alice de Leygrave became his foster mother. He probably did not know his natural mother, Eleanor, very well. She was in France with his father during his early years. A special household with staff was set up for the new baby. It was led by Giles of Oudenarde.

Growing Up and Personality

More money was spent on Edward's household as he grew up. In 1293, William of Blyborough took over as its manager. Edward likely received a religious education from Dominican friars. His mother invited them into his home in 1290. Guy Ferre, one of his grandmother's followers, was his magister. This person was in charge of his discipline and taught him riding and military skills.

It is not clear how well Edward was educated. There is little proof he could read and write. However, his mother wanted her other children to be well educated. Ferre himself was a learned man for that time. Edward probably spoke mostly Anglo-Norman French every day. He also knew some English and possibly Latin.

Edward had a normal childhood for a royal family member. He loved horses and horsebreeding and became a good rider. He also liked dogs, especially greyhounds. In his letters, he showed a funny side. He joked about sending bad animals to his friends. These included horses that disliked carrying riders or lazy hunting dogs. He was not very interested in hunting or falconry, which were popular at the time. He enjoyed music, including Welsh music and the crwth instrument. He also liked musical organs. He did not take part in jousting. This might have been because he was not good at it or for his safety. But he certainly supported the sport.

Edward grew up to be tall and strong. People at the time thought he was handsome. He was known as a good public speaker. He was also generous to his household staff. Unusually for a noble, he enjoyed rowing. He also liked hedging and ditching. He enjoyed spending time with laborers and other working-class people. This behavior was not common for nobles. It caused some criticism from people at the time.

In 1290, Edward's father agreed to the Treaty of Birgham. This treaty promised to marry six-year-old Edward to Margaret, Maid of Norway. She had a possible claim to the Scottish crown. Margaret died later that year, ending the plan. Edward's mother, Eleanor, died soon after. Then his grandmother, Eleanor of Provence, also passed away. Edward I was very sad about his wife's death and held a huge funeral. His son inherited the County of Ponthieu from Eleanor.

Next, a French marriage was considered for young Edward. This was to help secure peace with France. But war broke out in 1294. The idea was replaced with a marriage proposal to a daughter of Guy, Count of Flanders. But this also failed because King Philip IV of France blocked it.

Early Military Experience in Scotland

Between 1297 and 1298, Edward was left in charge of England as regent. This was while his father was fighting in Flanders. When his father returned, he signed a peace treaty. Under this treaty, he married Philip IV's sister, Margaret. They also agreed that Prince Edward would marry Philip's daughter, Isabella. She was only two years old at the time. This marriage was supposed to help solve problems over the Duchy of Gascony. The young Edward seemed to get along well with his new stepmother. She gave birth to Edward's two half-brothers, Thomas and Edmund. As king, Edward later gave his brothers money and titles.

Edward I went back to Scotland in 1300. This time, he took his son with him. He made Edward the commander of the rearguard at the siege of Caerlaverock Castle. In 1301, the king declared Edward the Prince of Wales. He also gave him the earldom of Chester and lands in North Wales. The king hoped this would help calm the region. It would also give his son some financial independence. Edward received loyalty from his Welsh subjects. Then he joined his father for the 1301 Scottish campaign. He took an army of about 300 soldiers north and captured Turnberry Castle. Prince Edward also took part in the 1303 campaign. He besieged Brechin Castle using his own siege engine. In 1304, Edward talked with the rebel Scottish leaders for the king. When these talks failed, he joined his father at the siege of Stirling Castle.

In 1305, Edward and his father had an argument. It was probably about money. The prince had a disagreement with Bishop Walter Langton, the royal treasurer. This was about how much money Edward received from the Crown. The king supported his treasurer. He banished Prince Edward and his friends from his court. He also cut off their money. After some talks, the two were reconciled.

The Scottish conflict started again in 1306. Robert the Bruce killed his rival and declared himself King of the Scots. Edward I gathered a new army. This time, his son was formally in charge of the trip. Prince Edward was made the duke of Aquitaine. Then, he and many other young men were knighted in a grand ceremony. This event was called the Feast of the Swans. During a huge feast, everyone swore to defeat Bruce. It is not clear what role Prince Edward's forces played in the campaign that summer. Edward I ordered a harsh response against Bruce's group in Scotland. Edward returned to England in September. Talks continued to set a date for his wedding to Isabella.

Early Reign (1307–1311)

Becoming King and Marriage

Edward I gathered another army for Scotland in 1307. Prince Edward was supposed to join that summer. But the old king had been sick and died on 7 July. Edward traveled from London right away. On 20 July, he was announced as king. He went north into Scotland. On 4 August, he received loyalty from his Scottish supporters. Then he stopped the campaign and went back south.

Edward quickly called back Piers Gaveston, who was in exile. He made Gaveston Earl of Cornwall. He also arranged Gaveston's marriage to the rich Margaret de Clare. Edward also arrested his old enemy, Bishop Langton, and removed him from his job. Edward I's body was kept at Waltham Abbey for months. Then it was buried at Westminster, where Edward built a simple tomb for his father.

In 1308, Edward's marriage to Isabella of France went ahead. Edward crossed the English Channel to France in January. He left Gaveston in charge of the kingdom. This was unusual. Gaveston was given a lot of power. Edward probably hoped the marriage would make him stronger in France. He also hoped it would bring him much-needed money. The final talks were hard. Edward and Philip IV did not like each other. The French king made tough demands about Isabella's dower (money/property) and how Edward's lands in France would be run. As part of the deal, Edward showed loyalty to Philip for the Duchy of Aquitaine. He also agreed to finish the 1303 peace treaty.

They were married in Boulogne on 25 January. Edward gave Isabella a psalter (a book of psalms) as a wedding gift. Her father gave her gifts worth over 21,000 French livres. He also gave her a piece of the True Cross. They returned to England in February. Edward had ordered Westminster Palace to be beautifully fixed up for their coronation and wedding feast. It had marble tables, forty ovens, and a fountain that made wine.

The ceremony happened on 25 February at Westminster Abbey. Bishop Henry Woodlock led it. Edward promised to follow "the rightful laws and customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen." It is not clear what this meant. It might have been to make Edward accept future laws. Or it might have been to stop him from breaking promises. Or it might have been a way for the king to get along with the barons. The event was messy. Large crowds rushed into the palace, knocking down a wall. Edward had to escape through a back door.

Isabella was only twelve when she married. This was young even for that time. During their first few years, Edward had an illegitimate son, Adam, born around 1307. Edward and Isabella's first son, the future Edward III, was born in 1312. There were big celebrations. Three more children followed: John in 1316, Eleanor in 1318, and Joan in 1321.

Problems with Gaveston

When Gaveston came back in 1307, the barons first accepted it. But soon, people started to oppose him. He seemed to have too much power over the king. One writer complained that there were "two kings reigning in one kingdom." People accused Gaveston of stealing royal money and Isabella's wedding gifts. These claims were probably not true. Gaveston played a big part in Edward's coronation. This made both English and French groups very angry. They were upset about Gaveston's fancy clothes and high rank. They also noticed Edward seemed to prefer Gaveston's company over Isabella's at the feast.

Parliament met in February 1308. The mood was tense. Edward wanted to talk about government changes. But the barons refused until Gaveston was dealt with. Violence seemed likely. But Henry de Lacy, a moderate leader, helped calm things. He convinced the barons to back down. A new parliament was held in April. The barons again criticized Gaveston and demanded he be sent away. This time, Isabella and the French king supported them. Edward resisted but finally agreed. He sent Gaveston to France. He was threatened with being kicked out of the Church if he returned. At the last minute, Edward changed his mind. He sent Gaveston to Dublin instead, making him the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Edward called for a new military trip to Scotland. But this idea was dropped. Instead, the king and barons met in August 1308 to talk about reforms. Edward secretly started talks to convince the Pope and Philip IV to let Gaveston return. In exchange, he offered to stop the Knights Templar in England. He also offered to free Bishop Langton from prison. Edward called a new meeting of Church members and key barons in January 1309. The leading earls then met in March and April. Another parliament followed. It refused to let Gaveston return. But it offered to give Edward more taxes if he agreed to a reform plan.

Edward told the Pope that the conflict over Gaveston was over. Based on these promises, the Pope allowed Gaveston to return. Gaveston arrived back in England in June. Edward met him there. At parliament the next month, Edward made many promises to calm those against Gaveston. He agreed to limit the powers of royal officials. He also agreed to stop unpopular ways of getting supplies. And he would drop new customs laws. In return, parliament agreed to new taxes for the war in Scotland. For a while, Edward and the barons seemed to have found a good compromise.

The Ordinances of 1311

After Gaveston returned, his relationship with the main barons got worse. He was seen as arrogant. He even gave insulting nicknames to the earls. The Earl of Lancaster and Gaveston's enemies refused to attend parliament in 1310. This was because Gaveston would be there. Edward was facing money problems. He owed £22,000 to his Italian bankers. He also faced protests about how he was getting supplies for the war in Scotland. His attempts to raise an army for Scotland failed. The earls stopped collecting the new taxes.

The king and parliament met again in February 1310. Talks about Scotland were replaced by talks about problems in England. Edward was asked to remove Gaveston as his advisor. Instead, he should take advice from 21 elected barons, called Ordainers. These Ordainers would make big changes to the government and the royal household. Under great pressure, Edward agreed. The Ordainers were chosen. They were split between reformers and conservatives. While the Ordainers planned reforms, Edward and Gaveston took a new army of about 4,700 men to Scotland. The military situation there had gotten worse. Robert the Bruce refused to fight. The campaign did not achieve much over the winter. Supplies and money ran out in 1311. Edward had to return south.

By then, the Ordainers had written their Ordinances for reform. Edward had little choice but to accept them in October. The Ordinances of 1311 had rules limiting the king's right to go to war or give away land without parliament's approval. They gave parliament control over the royal government. They also ended the system of taking supplies. They removed the Italian bankers. And they set up a system to check if the Ordinances were followed. Also, the Ordinances sent Gaveston away again. This time, he was not allowed to live anywhere in Edward's lands. Edward went to his estates at Windsor and Kings Langley. Gaveston left England, possibly for northern France.

Middle Reign (1311–1321)

Gaveston's Death

Tensions between Edward and the barons stayed high. The earls who opposed the king kept their armies ready in late 1311. By now, Edward was estranged from his cousin, the Earl of Lancaster. Lancaster was also the Earl of Leicester, Lincoln, Salisbury, and Derby. He had an income of about £11,000 a year from his lands. This was almost double that of the next richest baron. Lancaster led a powerful group in England. But he was not very interested in running the government. He was also not a very creative or effective politician.

Edward reacted to the barons' threat by canceling the Ordinances. He called Gaveston back to England. They met again at York in January 1312. The barons were furious. They met in London, where the Archbishop of Canterbury kicked Gaveston out of the Church. Plans were made to capture Gaveston. Edward, Isabella, and Gaveston left for Newcastle. Lancaster and his followers chased them. The royal group left many of their things. They fled by ship and landed at Scarborough. Gaveston stayed there while Edward and Isabella returned to York.

After a short siege, Gaveston surrendered to the earls of Pembroke and Surrey. They promised he would not be harmed. He had a huge collection of gold, silver, and jewels with him. This was probably part of the royal treasury. He was later accused of stealing it from Edward.

On the way back from the north, Pembroke stopped in the village of Deddington. He left Gaveston under guard there while he visited his wife. The Earl of Warwick used this chance to seize Gaveston. He took him to Warwick Castle. The Earl of Lancaster and his group met there on 18 June. In a quick trial, Gaveston was found guilty of being a traitor. He was executed on Blacklow Hill the next day. This was done under Lancaster's authority. Gaveston's body was not buried until 1315. His funeral was held in King's Langley Priory.

Problems with Lancaster and France

People reacted differently to Gaveston's death. Edward was furious and very sad. He saw it as murder. He made sure Gaveston's family was provided for. He planned to get revenge on the barons involved. The earls of Pembroke and Surrey were embarrassed and angry about Warwick's actions. They then supported Edward. For Lancaster and his main supporters, the execution was legal and necessary. It was needed to keep the kingdom stable.

Civil war seemed likely again. But in December, the Earl of Pembroke arranged a possible peace treaty. It would pardon the barons for killing Gaveston. In return, they would support a new campaign in Scotland. However, Lancaster and Warwick did not agree right away. More talks continued through most of 1313.

Meanwhile, the Earl of Pembroke had been talking with France. They wanted to solve old disagreements about Gascony. As part of this, Edward and Isabella agreed to go to Paris in June 1313. They would meet with Philip IV. Edward probably hoped to solve problems in France. He also hoped to get Philip's support in his dispute with the barons. For Philip, it was a chance to show his power and wealth to his son-in-law.

It was a spectacular visit. It included a grand ceremony where the two kings knighted Philip's sons and two hundred other men in Notre-Dame de Paris. There were large feasts along the River Seine. They also publicly declared that both kings and queens would join a crusade to the Middle East. Philip gave easy terms for solving the problems in Gascony. The event was only spoiled by a serious fire in Edward's rooms.

When he returned from France, Edward found his political position much stronger. After intense talks, the earls, including Lancaster and Warwick, reached a compromise in October 1313. It was very similar to the earlier agreement. Edward's money situation improved. Parliament agreed to raise taxes. The Pope gave a loan of £25,000. Philip loaned £33,000. Edward's new Italian banker, Antonio Pessagno, arranged more loans. For the first time in his reign, Edward's government had enough money.

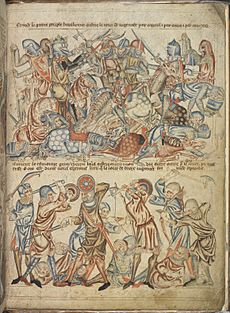

Battle of Bannockburn

By 1314, Robert the Bruce had taken back most of the castles in Scotland that Edward once held. He was also sending raiding parties into northern England. These raids reached as far south as Carlisle. In response, Edward planned a major military campaign. He had the support of Lancaster and the barons. He gathered a large army of 15,000 to 20,000 men.

Meanwhile, Robert had surrounded Stirling Castle, a key fort in Scotland. Its English commander said he would surrender if Edward did not arrive by 24 June. News of this reached the king in late May. He decided to speed up his march north from Berwick-upon-Tweed to help the castle. Robert, with 5,500 to 6,500 troops, mostly spearmen, prepared to stop Edward's forces from reaching Stirling.

The battle started on 23 June. The English army tried to cross the high ground of the Bannock Burn. This area was surrounded by marshland. Small fights broke out between the two sides. Sir Henry de Bohun was killed by Robert in a personal fight. Edward continued his advance the next day. He met the main Scottish army as they came out of the woods. Edward did not seem to expect the Scots to fight here. So, his forces were in marching order, not battle order. The archers, who usually broke up enemy spear groups, were at the back. His cavalry struggled in the tight space and were crushed by Robert's spearmen. The English army was overwhelmed. Its leaders could not regain control.

Edward stayed to fight. But it became clear to the Earl of Pembroke that the battle was lost. He pulled the king away from the battlefield. Scottish forces chased them closely. Edward barely escaped the heavy fighting. He promised to build a Carmelite religious house at Oxford if he survived. Historian Roy Haines calls the defeat a "calamity of stunning proportions" for the English. Their losses in the battle were huge. After the defeat, Edward went to Dunbar. Then he traveled by ship to Berwick, and back to York. In his absence, Stirling Castle quickly fell.

Famine and Growing Criticism

After the disaster at Bannockburn, the earls of Lancaster and Warwick gained more political power. They pressured Edward to bring back the Ordinances of 1311. Lancaster became the head of the royal council in 1316. He promised to push for the Ordinances through a new reform group. But he seemed to give up this role soon after. This was partly due to disagreements with other barons. It might also have been because he was sick. Lancaster refused to meet with Edward in parliament for the next two years. This stopped effective government. It also ended hopes for a new campaign into Scotland. Fears of civil war grew. After many talks, Edward and Lancaster finally agreed to the Treaty of Leake in August 1318. This pardoned Lancaster and his group. It also set up a new royal council, stopping conflict for a while.

Edward's problems got worse because of long-lasting issues in English farming. This was part of a larger problem in northern Europe called the Great Famine. It started with heavy rains in late 1314. A very cold winter followed, then heavy rains the next spring. Many sheep and cattle died. The bad weather continued, almost without stopping, until 1321. This led to many bad harvests. Money from wool exports dropped sharply. The price of food rose, even though Edward's government tried to control prices. Edward asked people hoarding food to release it. He tried to encourage trade and importing grain, but with little success. Taking supplies for the royal court during the famine years only added to the problems.

Meanwhile, Robert the Bruce used his victory at Bannockburn to raid northern England. He first attacked Carlisle and Berwick. Then he went further south into Lancashire and Yorkshire, even threatening York itself. Edward led an expensive but unsuccessful campaign in 1319 to stop the advance. But the famine made it harder to supply his garrisons with food. Meanwhile, a Scottish group led by Robert's brother, Edward Bruce, successfully invaded Ireland in 1315. Edward Bruce declared himself the High King of Ireland. He was finally defeated in 1318 by Edward II's Irish official, Edmund Butler. Revolts also broke out in Lancashire and Bristol in 1315. There was also a revolt in Glamorgan in Wales in 1316. But these were put down.

The famine and the Scottish policy were seen as punishment from God. Complaints about Edward increased. One poem from the time described the "Evil Times of Edward II." Many criticized Edward's "improper" interest in farming activities. In 1318, a mentally ill man named John of Powderham appeared in Oxford. He claimed he was the real Edward II, and that Edward was a changeling (a child secretly swapped at birth). John was executed. But his claims resonated with those who criticized Edward for his lack of kingly behavior and steady leadership. Opposition also grew because of Edward's treatment of his royal favorites.

Edward had managed to keep some of his old advisors. He divided the large de Clare inheritance between two of his new favorites. These were former household knights Hugh Audley and Roger Damory. This instantly made them very rich. Many of the moderate nobles who had helped make peace in 1318 now started to turn against Edward. This made violence even more likely.

Later Reign and Downfall (1321–1327)

The Despenser War

The long-feared civil war finally began in England in 1321. It was caused by tension between many barons and the royal favorites, the Despenser family. Hugh Despenser the Elder had served both Edward and his father. Hugh Despenser the Younger married into the rich de Clare family. He became the King's chamberlain and gained land in Glamorgan in Wales in 1317. Hugh the Younger then expanded his lands and power across Wales. This was mostly at the expense of other powerful lords.

The Earl of Lancaster and the Despensers were strong enemies. Most of the Despensers' neighbors also disliked them. These included the Earl of Hereford, the Mortimer family, and the recently rich Hugh Audley and Roger Damory. Edward, however, relied more and more on the Despensers for advice and support. He was especially close to Hugh the Younger. One writer noted Edward "loved... dearly with all his heart and mind."

In early 1321, Lancaster gathered a group of the Despensers' enemies. Edward and Hugh the Younger learned of these plans in March. They went west, hoping talks would stop the crisis. But this time, Pembroke refused to help. War broke out in May. The Despensers' lands were quickly taken by the Marcher Lords and local gentry. Lancaster held a meeting of barons and clergy in June. They said the Despensers had broken the Ordinances. Edward tried to make peace. But in July, the opposition took over London. They called for the Despensers to be removed permanently. Fearing he might be removed from power, Edward agreed to exile the Despensers. He also pardoned the Marcher Lords for their actions.

Edward began to plan his revenge. With Pembroke's help, he formed a small group. It included his half-brothers, some earls, and senior clergy. He prepared for war. Edward started with Bartholomew de Badlesmere, 1st Baron Badlesmere. Isabella was sent to Bartholomew's castle, Leeds Castle. This was to create a reason for war. Bartholomew's wife, Margaret, fell for the trap. Her men killed some of Isabella's group. This gave Edward an excuse to act. Lancaster refused to help Bartholomew, his enemy. Edward quickly took back control of south-east England.

Alarmed, Lancaster now gathered his own army in the north. Edward gathered his forces in the south-west. The Despensers returned from exile and were pardoned. In December, Edward led his army across the River Severn. He moved into Wales, where the opposition forces had gathered. The Marcher Lords' group fell apart. The Mortimers surrendered to Edward. But Damory, Audley, and the Earl of Hereford marched north in January. They joined Lancaster, who was besieging the king's castle at Tickhill. Edward pursued them. He met Lancaster's army on 10 March at Burton-on-Trent. Lancaster, outnumbered, retreated without a fight. He fled north. Andrew Harclay trapped Lancaster at the Battle of Boroughbridge. He captured the earl. Edward and Hugh the Younger met Lancaster at Pontefract Castle. After a quick trial, the earl was found guilty of treason and beheaded.

Edward and the Despensers' Rule

Edward punished Lancaster's supporters using special courts. Judges were told in advance how to sentence the accused. The accused were not allowed to speak in their own defense. Many of these "Contrariants" were executed. Others were imprisoned or fined. Their lands were taken, and their families were held. The Earl of Pembroke, whom Edward now distrusted, was arrested. He was released only after promising all his possessions as security for his loyalty. Edward rewarded his loyal supporters, especially the Despenser family. He gave them the confiscated lands and new titles.

The fines and land seizures made Edward rich. Almost £15,000 was collected in the first few months. By 1326, Edward's treasury had £62,000. A parliament was held at York in March 1322. The Ordinances were formally canceled. New taxes were agreed for a new campaign against the Scots.

The English campaign against Scotland was planned to be very large. It had about 23,000 men. Edward moved through Lothian towards Edinburgh. But Robert the Bruce refused to fight him. This drew Edward further into Scotland. Plans to resupply the army by sea failed. The large army quickly ran out of food. Edward was forced to retreat south, chased by Scottish raiding parties. Edward's illegitimate son, Adam, died during the campaign. The raiding parties almost captured Isabella, who was staying at Tynemouth. She had to flee by sea. Edward planned a new campaign, with more taxes. But trust in his Scottish policy was decreasing.

Andrew Harclay, who helped Edward win battles the previous year, made a peace treaty with Robert the Bruce. He suggested Edward recognize Robert as King of Scotland. In return, Robert would stop interfering in England. Edward was furious and immediately executed Harclay. But he agreed to a thirteen-year truce with Robert.

Hugh Despenser the Younger lived and ruled in a grand way. He played a main role in Edward's government. He carried out policies through his family and followers. Supported by Chancellor Robert Baldock and Lord Treasurer Walter Stapledon, the Despensers gained land and wealth. They used their government positions to hide their fraud, threats, and abuse of legal rules. Meanwhile, Edward faced growing opposition. Miracles were reported at Lancaster's tomb. Law and order began to break down. This was made worse by the taking of lands. Old enemies tried to free prisoners Edward held. Roger Mortimer, a prominent Marcher Lord, escaped from the Tower of London and fled to France.

War with France

Disagreements between Edward and the French King over Gascony led to the War of Saint-Sardos in 1324. Charles, Edward's brother-in-law, became King of France in 1322. He was more aggressive than past kings. In 1323, he insisted Edward come to Paris to show loyalty for Gascony. He also demanded that Edward's officials in Gascony allow French officials to carry out orders from Paris. In 1324, Edward sent the Earl of Pembroke to Paris to find a solution. But the earl suddenly died on the way. Charles gathered his army and ordered the invasion of Gascony.

Edward's forces in Gascony were about 4,400 strong. But the French army, led by Charles of Valois, had 7,000 men. Valois took the Agenais region. Then he advanced further and cut off the main city of Bordeaux. In response, Edward ordered the arrest of any French people in England. He also seized Isabella's lands because she was French. In November 1324, he met with the earls and the English Church. They suggested Edward lead a force of 11,000 men to Gascony. Edward decided not to go himself. He sent the Earl of Surrey instead.

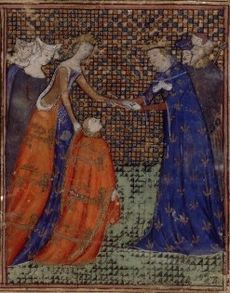

Meanwhile, Edward started new talks with the French king. Charles made various proposals. The most tempting was that if Isabella and Prince Edward went to Paris, and the Prince showed loyalty to Charles for Gascony, the war would end. And the Agenais would be returned. Edward and his advisors worried about sending the prince to France. But they agreed to send Isabella alone as an envoy in March 1325.

Edward's Fall from Power (1326–1327)

Isabella Turns Against Edward

Isabella and Edward's envoys talked with the French in late March. The talks were difficult. They reached an agreement only after Isabella personally spoke with her brother, Charles. The terms favored the French King. Edward would have to show loyalty in person to Charles for Gascony. Edward worried about war starting again. He agreed to the treaty. But he decided to give Gascony to his son, Edward. He sent the prince to show loyalty in Paris. Young Prince Edward crossed the English Channel and completed the deal in September.

Edward now expected Isabella and their son to return to England. But she stayed in France and showed no sign of coming back. Until 1322, Edward and Isabella's marriage seemed fine. But by the time Isabella left for France in 1325, it had gotten worse. Isabella seemed to strongly dislike Hugh Despenser the Younger. Isabella was embarrassed that she had fled from Scottish armies three times during her marriage. She blamed Hugh for the last time in 1322. When Edward made the truce with Robert the Bruce, he badly affected many noble families who owned land in Scotland. These included the Beaumonts, who were close friends of Isabella. She was also angry about her household being arrested and her lands being taken in 1324. Finally, Edward had taken her children and given them to Hugh Despenser's wife.

By February 1326, it was clear that Isabella was in a relationship with an exiled lord, Roger Mortimer. It is not clear when Isabella first met Mortimer or when their relationship began. But they both wanted to remove Edward and the Despensers from power. Edward asked for his son to return. He also asked Charles to help him. But this had no effect.

Edward's opponents started to gather around Isabella and Mortimer in Paris. Edward became more and more worried that Mortimer might invade England. Isabella and Mortimer turned to William I, Count of Hainaut. They suggested a marriage between Prince Edward and William's daughter, Philippa. In return for this good alliance with the English heir, and a large dowry for the bride, William offered 132 ships and eight warships to help invade England. Prince Edward and Philippa were engaged on 27 August. Isabella and Mortimer prepared for their campaign.

The Invasion of England

During August and September 1326, Edward prepared his defenses along the English coasts. This was to protect against a possible invasion by France or Roger Mortimer. Fleets were gathered at ports like Portsmouth and Orwell. A raiding force of 1,600 men was sent across the English Channel to Normandy as a distraction. Edward made a patriotic appeal for his subjects to defend the kingdom. But it had little impact. The government's control at the local level was weak. The Despensers were widely disliked. Many people Edward trusted to defend the kingdom proved unable or quickly turned against him. About 2,000 men were ordered to gather at Orwell to stop any invasion. But only 55 actually arrived.

Roger Mortimer, Isabella, and thirteen-year-old Prince Edward landed in Orwell on 24 September. They had a small force and met no resistance. Instead, enemies of the Despensers quickly joined them. These included Edward's half-brother, Thomas of Brotherton. Also, Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, who had inherited the earldom from his brother Thomas, joined them. Many senior clergy also joined. Edward was safe in the Tower of London. He tried to get support from within the capital. But the city of London rose against his government. On 2 October, he left London, taking the Despensers with him. London fell into chaos. Mobs attacked Edward's remaining officials and friends. They killed his former treasurer Walter Stapledon in St Paul's Cathedral. They also took the Tower and freed the prisoners inside.

Edward continued west up the Thames Valley. He reached Gloucester between 9 and 12 October. He hoped to reach Wales and gather an army there. Mortimer and Isabella were not far behind. Proclamations condemned the Despensers' recent rule. Day by day, they gained new supporters. Edward and the younger Despenser crossed the border. They sailed from Chepstow. They probably aimed for Lundy and then Ireland. The king hoped to find safety there and raise a new army. Bad weather forced them back. They landed at Cardiff. Edward retreated to Caerphilly Castle. He tried to rally his remaining forces.

Edward's power collapsed in England. In his absence, Isabella's group took over the government with the Church's support. Her forces surrounded Bristol, where Hugh Despenser the Elder had taken shelter. He surrendered and was quickly executed. Edward and Hugh the Younger fled their castle around 2 November. They left behind jewels, supplies, and at least £13,000 in cash. They possibly hoped to reach Ireland again. But on 16 November, they were betrayed and captured north of Caerphilly. Edward was taken first to Monmouth Castle. From there, he was taken back into England. He was held at the Earl of Lancaster's castle at Kenilworth. Edward's last remaining forces, besieged in Caerphilly Castle, surrendered after four months in March 1327.

Edward's Abdication

Isabella and Mortimer quickly took revenge on the old government. Hugh Despenser the Younger was put on trial. He was declared a traitor and sentenced to death. He was executed on 24 November 1326. Edward's former chancellor, Robert Baldock, died in Fleet Prison. The Earl of Arundel was beheaded.

Edward's situation was difficult. He was still married to Isabella. In principle, he was still the king. But most of the new government had a lot to lose if he were released. There was no set way to remove an English king. Adam Orleton, the bishop of Hereford, made public accusations about Edward's behavior as king. In January 1327, a parliament met at Westminster. The question of Edward's future was raised. Edward refused to attend. Parliament, at first unsure, responded to the London crowds. The crowds called for the king's son Edward to take the throne.

On 12 January, the leading barons and clergy agreed that Edward II should be removed. His son would replace him. The next day, it was presented to an assembly of barons. They argued that Edward's weak leadership and personal faults had led the kingdom to disaster. They said he was unable to lead the country.

Soon after, a group of barons, clergy, and knights was sent to Kenilworth to speak to the king. On 20 January 1327, the Earl of Lancaster and the bishops of Winchester and Lincoln met privately with Edward in the castle. They told Edward that if he resigned as king, his son Edward would succeed him. But if he refused, his son might also lose his right to the crown. The crown could be given to someone else. In tears, Edward agreed to step down. On 21 January, Sir William Trussell, representing the kingdom, formally ended Edward's reign. A public announcement was sent to London. It said that Edward, now called Edward of Caernarvon, had freely given up his kingdom. His son Edward would succeed him. The coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on 1 February 1327.

Edward's Death and Legacy (1327)

Death and Aftermath

Those against the new government started to plan to free Edward. Roger Mortimer decided to move him to the more secure Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire. Edward arrived there around 5 April 1327. At the castle, he was held by Mortimer's son-in-law, Thomas de Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley, and John Maltravers. They were paid £5 a day to care for Edward. It is unclear how well Edward was cared for. Records show luxury goods were bought for him. But some writers suggest he was often mistreated. A poem, the "Lament of Edward II", has been linked to Edward during his imprisonment by some scholars, but this is debated.

Concerns continued about new plots to free Edward. Some involved the Dominican order and former knights. One attempt even broke into the prison within the castle. Because of these threats, Edward was secretly moved to other places for a time. He returned to permanent custody at the castle in late summer 1327. The political situation remained unstable. New plots seemed to form to free him.

On 23 September, Edward III was told that his father had died at Berkeley Castle during the night of 21 September. Most historians agree Edward II died at Berkeley on that date. However, a few believe he died much later. His death was, as historian Mark Ormrod notes, "suspiciously timely." It greatly simplified Mortimer's political problems. Most historians believe Edward was probably murdered on the orders of the new rulers. But it is impossible to be certain. Several people suspected of being involved in the death later fled. If Edward died naturally, his death may have been sped up by depression after his imprisonment.

The rule of Isabella and Mortimer did not last long after Edward's death was announced. They made peace with the Scots in the Treaty of Northampton. But this was very unpopular. Isabella and Mortimer both gained and spent a lot of wealth. Criticism of them grew. Relations between Mortimer and Edward III became strained. In 1330, the king carried out a coup d'état at Nottingham Castle. He arrested Mortimer and then executed him. He was charged with fourteen counts of treason, including the murder of Edward II. Edward III's government tried to blame Mortimer for all the recent problems. This effectively made Edward II look better politically. Edward III spared Isabella. He gave her a generous allowance, and she soon returned to public life.

Burial and Tomb

Edward's body was prepared at Berkeley Castle. Local leaders from Bristol and Gloucester viewed it. It was then taken to Gloucester Abbey on 21 October. On 20 December, Edward was buried by the high altar. The funeral was probably delayed so Edward III could attend. Gloucester was likely chosen because other abbeys had refused or were forbidden to take the king's body. It was also close to Berkeley. The funeral was a grand event and cost £351. It included gilt lions, flags painted with gold, and barriers to manage the expected crowds. Edward III's government probably hoped to make recent political events seem normal. This would increase the young king's own legitimacy.

A temporary wooden effigy (a statue) with a copper crown was made for the funeral. This is the first known use of a funeral effigy in England. It was probably needed because of the condition of the King's body, as he had been dead for three months. Edward's heart was removed. It was placed in a silver container and later buried with Isabella in London. His tomb includes a very early example of an English alabaster statue. It has a tomb chest and a canopy made of stone. Edward was buried in the shirt, cap, and gloves from his coronation. His statue shows him as king, holding a sceptre and orb, and wearing a crown. The statue has a noticeable lower lip, and may be a good likeness of Edward.

Edward II's tomb quickly became a popular place for visitors. This was probably encouraged by the local monks. They did not have another popular pilgrimage site. Visitors gave a lot of money to the abbey. This allowed the monks to rebuild much of the surrounding church in the 1330s. Miracles were reportedly happening at the tomb. Changes had to be made to allow more visitors to walk around it. The writer Geoffrey le Baker described Edward as a saintly martyr. Richard II supported an unsuccessful attempt to have Edward made a saint in 1395. The tomb was opened by officials in 1855. They found a wooden coffin, still in good condition, and a sealed lead coffin inside it. The tomb remains in what is now Gloucester Cathedral. It was extensively restored in 2007 and 2008 at a cost of over £100,000.

Edward's Rule and Government

How Edward Ruled

Edward was not a successful king. Historian Michael Prestwich says he "was lazy and incompetent." He was prone to getting angry over small things. But he was unsure when it came to big problems. Roy Haines described Edward as "incompetent and vicious." He also called him "no man of business." Edward did not just let his officials handle daily government tasks. He also let them make important decisions. Historian Pierre Chaplais argues that he "was not so much an incompetent king as a reluctant one." Edward preferred to rule through a powerful helper, like Piers Gaveston or Hugh Despenser the Younger. Edward's willingness to promote his favorites caused serious political problems. But he also tried to gain the loyalty of other nobles by giving them money and titles. However, he could be very interested in small details of running the government. Sometimes he got involved in many different issues across England and his other lands.

One of Edward's constant challenges was a lack of money. Of the debts he inherited from his father, about £60,000 was still owed in the 1320s. Edward had many different treasurers and financial officials. Few of them stayed long. He raised money through often unpopular taxes. He also took goods using his right to take supplies. He also took out many loans. First, he borrowed from the Frescobaldi family, then from his banker Antonio Pessagno. Edward became very interested in money matters towards the end of his reign. He distrusted his own officials. He directly cut down on the expenses of his own household.

Edward was responsible for making sure royal justice was carried out. This was done through his judges and officials. It is unclear how much Edward personally cared about giving out justice. But he seemed to be involved somewhat in the first part of his reign. He seemed to get more involved in person after 1322. Edward often used Roman civil law during his reign. He used it when arguing for his causes and favorites. This may have been criticized by those who thought he was abandoning traditional English common law. Edward was also criticized for letting the Despensers use the royal justice system for their own benefit. The Despensers certainly seemed to abuse the system. But how widely they did so is unclear. During the political unrest, armed gangs and violence spread across England under Edward's rule. This made the position of many local landowners unstable. Much of Ireland also fell into chaos.

Under Edward's rule, parliament became more important. It was a way to make political decisions and answer requests. However, as historian Claire Valente notes, the meetings were "still as much an event as an institution." After 1311, parliament started to include representatives of the knights and townspeople. In later years, these would form the "commons." Although parliament often opposed raising new taxes, active opposition to Edward mostly came from the barons. It did not come from parliament itself. But the barons did try to use parliament meetings to make their political demands seem legitimate. After resisting for many years, Edward started to get involved in parliament in the second half of his reign. He did this to achieve his own political goals. It is still unclear if he was removed from power in 1327 by a formal parliament or just a gathering of political leaders.

Royal Court Life

Edward's royal court moved around the country with him. When it was at Westminster Palace, the court used two halls, seven rooms, and three chapels. It also had other smaller rooms. But because of the Scottish conflict, the court spent much of its time in Yorkshire and Northumbria. At the center of the court was Edward's royal household. This was divided into the "hall" and the "chamber." The size of the household changed over time. In 1317, it had about five hundred people. This included household knights, squires, and kitchen staff. The household was surrounded by a larger group of courtiers.

Music and musicians were very popular at Edward's court. But hunting seemed to be much less important. There was little focus on knightly events. Edward was interested in buildings and paintings. But he was less interested in books. These were not widely supported at court. There was a lot of gold and silver plates, jewels, and enamel work at court. These would have been richly decorated. Edward kept a camel as a pet. As a young man, he took a lion with him on a trip to Scotland. The court could be entertained in unusual ways. For example, in 1312, an Italian snake-charmer was invited.

Edward's Religious Views

Edward's approach to religion was normal for his time. Historian Michael Prestwich describes him as "a man of wholly conventional religious attitudes." There were daily chapel services and almsgiving (giving to the poor) at his court. Edward blessed the sick, though less often than kings before him. Edward remained close to the Dominican Order, who had helped educate him. He followed their advice in asking the Pope for permission to be anointed with holy oil in 1319. This request was refused, which caused the king some embarrassment. Edward supported the growth of universities during his reign. He established King's Hall in Cambridge to promote training in religious and civil law. He also founded Oriel College in Oxford and a short-lived university in Dublin.

Edward had a good relationship with Pope Clement V. This was despite the king often getting involved in how the English Church operated. He even punished bishops he disagreed with. With Clement's support, Edward tried to get financial help from the English Church for his military campaigns in Scotland. This included taxes and borrowing money from funds meant for crusades. The Church did little to influence or change Edward's behavior during his reign. This might have been because the bishops were self-interested and wanted to protect themselves.

Pope John XXII, elected in 1316, wanted Edward's support for a new crusade. He also tended to support Edward politically. In 1317, Edward agreed to start paying the annual Papal tribute again. This had first been agreed to by King John in 1213. This was in exchange for papal support in his war with Scotland. However, Edward soon stopped the payments. He never offered his loyalty, which was another part of the 1213 agreement. In 1325, Edward asked Pope John to tell the Irish Church to openly preach in favor of his right to rule Ireland. He also asked him to threaten to kick out anyone who spoke against it.

Edward's Legacy

How Historians See Edward

No writer from this period is completely trustworthy or fair. Their accounts were often written to support a certain cause. But it is clear that most writers at the time were very critical of Edward. Books like the Polychronicon and Vita Edwardi Secundi all criticized the king's personality, habits, and choice of friends. Other records from his reign show criticism from his contemporaries. This included the Church and members of his own household. Political songs were written about him. They complained about his failures in war and his harsh government. Later in the 14th century, some writers, like Geoffrey le Baker, presented Edward in a better light. They showed him as a martyr and a possible saint. But this idea faded in later years.

By the late 1800s, more government records from the period became available. Historians like William Stubbs and Thomas Tout focused on how the English government system developed during Edward's reign. They criticized what they saw as Edward II's weaknesses as a king. But they also highlighted the growth of parliament's role and the reduction in the king's personal power. They saw these as positive developments.

During the 1970s, the way historians viewed Edward's reign changed. New records published later in the 20th century supported this. Historians like Jeffrey Denton and Seymour Phillips focused attention on the role of individual leaders in the conflicts. For many years, major historical studies focused on the powerful nobles rather than Edward himself. This changed when detailed biographies of the king were published by Roy Haines and Seymour Phillips in the early 2000s.

Edward's Children

Edward II had four children with Isabella:

- Edward III of England (born 13 November 1312 – died 21 June 1377). He married Philippa of Hainault on 24 January 1328 and had children.

- John of Eltham (born 15 August 1316 – died 13 September 1336). He never married and had no children.

- Eleanor of Woodstock (born 18 June 1318 – died 22 April 1355). She married Reinoud II of Guelders in May 1332 and had children.

- Joan of the Tower (born 5 July 1321 – died 7 September 1362). She married David II of Scotland on 17 July 1328 and became Queen of Scots, but had no children.

Edward also had an illegitimate son named Adam FitzRoy (born around 1307 – died 1322). Adam went with his father on the Scottish campaigns in 1322 and died soon after.

Images for kids

-

Effigy in Gloucester Cathedral

-

Caernarfon Castle, Edward's birthplace

-

Painting in Westminster Abbey, thought to be of Edward's father, Edward I

-

Isabella of France (third from the left) with her father, Philip IV of France (tallest)

-

Edward (left) and Philip IV at the knighting ceremony of Notre Dame, 1312

-

Depiction of the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 from the Holkham Bible

-

The future Edward III giving homage in 1325 to Charles IV under the guidance of Isabella of France

-

Replica of the Oxwich Brooch, probably owned by Edward and looted during the events of 1326

-

Covered walkway leading to a cell within Berkeley Castle, by tradition associated with Edward's imprisonment

-

Edward II's tomb at Gloucester Cathedral

-

1575 map of Cambridge showing the King's Hall (top left) founded by Edward

-

Oriel College's 1326 charter from Edward

-

Edward's coat of arms as king

See also

In Spanish: Eduardo II de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Eduardo II de Inglaterra para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |