Ordinances of 1311 facts for kids

The Ordinances of 1311 were a set of rules created by important nobles and church leaders in England. These rules were designed to limit the power of King Edward II. The twenty-one people who signed these rules were called the Lords Ordainers.

England was struggling in a war with Scotland, and many people felt the king was spending too much money unfairly. These problems led to the creation of the Ordinances. The new rules took much of the king's power over how the government was run and gave it to a council of nobles. The Ordinances also focused on money, making sure the king's income went to the government treasury (the exchequer) instead of just his personal household.

Another big reason for the Ordinances was the dislike for the king's close friend, Piers Gaveston. The nobles eventually forced Gaveston to leave the country. King Edward II only accepted these rules because he had no choice. A long fight then began to get rid of the Ordinances, which finally ended when Thomas of Lancaster, the leader of the Ordainers, was executed in 1322.

Contents

Why the Rules Were Made

Early Troubles for the King

When Edward II became king on July 7, 1307, most people felt good about him. But problems were already starting. Some issues were left over from his father, King Edward I. Others were due to Edward II's own mistakes.

There were three main problems:

- War Costs: To pay for the war in Scotland, Edward I had often taken supplies like food for his soldiers without paying fairly. People felt this was too much, and they often didn't get paid at all. Edward II continued this practice, even when he wasn't fighting the Scots, which made people even angrier.

- Neglecting Scotland: While his father had fought hard against Scotland, Edward II almost completely stopped the war. This allowed the Scottish king, Robert Bruce, to win back lost land. This left northern England open to attacks and put the English nobles' lands in Scotland at risk.

- Piers Gaveston: The biggest problem was the king's favorite friend, Piers Gaveston. Gaveston was from a humble background, but the king gave him many honors, including the important title of Earl of Cornwall. This title was usually only given to members of the royal family. The nobles disliked Gaveston's special treatment and his arrogant behavior.

The nobles' anger first showed up in a statement made in Boulogne when the king was in France for his wedding. This statement, called the Boulogne agreement, hinted at worries about the king's court. When Edward II was crowned on February 25, 1308, his coronation oath was different. He had to promise to follow laws that the community "shall have chosen." This part of the oath was later used against him in his struggles with the nobles.

Gaveston Sent Away

In April 1308, the parliament decided that Gaveston had to leave England. The king had to agree, and Gaveston left on June 24 to become the Lieutenant of Ireland. But the king immediately started planning to bring his friend back.

In April 1309, the king suggested a deal: he would agree to some of the nobles' requests if Gaveston could return. This plan didn't work. However, Edward got the Pope to cancel the threat of excommunication against Gaveston. At the Stamford parliament in July, the king agreed to a new version of the Articuli super Cartas (a document his father had signed). With this, Gaveston was allowed to come back.

The nobles who agreed hoped Gaveston had learned his lesson. But when he returned, he was even more arrogant. He even gave insulting nicknames to some of the most powerful nobles. When the king called a meeting in October, several nobles refused to come because Gaveston was there.

At the parliament in February 1310, Gaveston was told not to attend. The nobles, ignoring the king's order not to carry weapons, arrived in full military gear. They demanded that the king appoint a group to reform the government. On March 16, 1310, the king agreed to appoint the Ordainers. Their job was to reform the royal household.

The Lords Ordainers

The Ordainers were chosen by a group of powerful nobles, not by common people. They were a mix of people: eight earls, seven bishops, and six barons – twenty-one in total. Some were loyal to the king, while others were strong opponents.

Among the loyal Ordainers was John of Brittany, Earl of Richmond, an older earl who had served Edward I and was Edward II's cousin. The natural leader of the group was Henry Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. He was one of the richest men in England and the oldest earl. He had served Edward I for a long time and was known for being fair. Lincoln helped keep the more extreme members of the group in check.

When Lincoln died in February 1311, his son-in-law, Thomas of Lancaster, took over. Lancaster was the king's cousin and now held five earldoms, making him the wealthiest man in the country, besides the king. It's not clear why Lancaster started opposing the king, but by the time the Ordinances were written, his opinion of Edward had clearly changed.

Lancaster's main ally was Guy Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Warwick was the most passionate and constant opponent of the king until his early death in 1315. Other earls were more flexible. Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, was Gaveston's brother-in-law and stayed loyal to the king. Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, later became a key supporter of the king, but at this time, he chose to go along with the reformers. Among the barons, Robert Clifford and William Marshall seemed to lean towards the king's side.

Among the bishops, two were important political figures. The most prominent was Robert Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury. He had a long history of fighting for the church's independence against Edward I, which led to his suspension and exile. One of Edward II's first acts as king was to bring Winchelsey back. But instead of being grateful, the archbishop soon became a leader in the fight against the king.

Edward II also held a grudge against another bishop, Walter Langton, Bishop of Lichfield. Edward removed Langton from his job as treasurer of the Exchequer and took his lands. Langton had been Winchelsey's opponent in the past, but Edward II's actions against Langton brought the two Ordainers together.

The Ordinances

Six early rules were released right after the Ordainers were appointed on March 19, 1310. But the committee didn't finish its main work until August 1311. Meanwhile, Edward had been on a failed military trip to Scotland. On August 16, parliament met in London, and the king was presented with the full Ordinances.

The document with the Ordinances is dated October 5 and has forty-one articles, or rules. In the introduction, the Ordainers said they were worried about the king's bad advisors, the difficult war situation abroad, and the risk of rebellion at home because of unfair taxes.

The rules can be grouped. The largest group deals with limiting the king's power and giving more control to the nobles. For example, the king had to appoint his officials only "with the advice and agreement of the baronage, and that in parliament." Also, the king could no longer go to war or change the money without the nobles' consent. It was also decided that parliament should meet at least once a year.

Alongside these rules were reforms for the royal finances. The Ordinances banned unfair taxes and customs. They also said that all royal income had to be paid directly into the Exchequer (the government treasury). This was a change from the king receiving money directly into his personal household. Making all royal money accountable to the Exchequer allowed for more public oversight.

Other rules focused on punishing specific people, especially Piers Gaveston. Rule 20 described Gaveston's wrongdoings in detail. He was again ordered to leave the country by November 1. The Italian bankers of the Frescobaldi company were arrested, and their money was taken. The Ordainers believed the king's heavy reliance on these Italians was bad for politics. The last people singled out for punishment were Henry de Beaumont and his sister, Isabella de Vesci. They were foreigners connected to the king's household. Their punishment might have been related to their lands being important in the Scottish war.

The Ordainers also confirmed and added to existing laws and made changes to criminal law. The church's freedoms were also confirmed. To make sure no Ordainer was bribed by the king, rules were made about what royal gifts and jobs they could receive while they were working on the Ordinances.

What Happened Next

The Ordinances were widely shared on October 11, hoping to get a lot of public support. For the next ten years, there was a constant struggle over whether they would be canceled or remain in effect. They were not finally canceled until May 1322, but how strongly they were followed depended on who was in charge of the government.

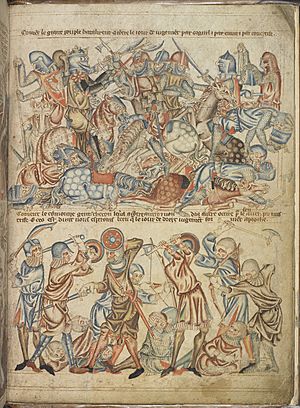

Before the end of 1311, Gaveston returned to England, and it looked like a civil war was about to begin. In May 1312, Gaveston was captured by the Earl of Pembroke. But Warwick and Lancaster kidnapped him and had him executed after a quick, unfair trial. This insult to Pembroke made him a strong supporter of the king, which split the group opposing the king.

The harshness of Gaveston's killing initially pushed Lancaster and his supporters away from power. But the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1314 changed things. Edward was humiliated by his terrible defeat. Lancaster and Warwick had not taken part in the battle, saying it was fought without the nobles' consent, which went against the Ordinances.

After this, Lancaster had almost complete control of the government. However, he became more isolated, especially after Warwick died in 1315. In August 1318, an agreement called the "Treaty of Leake" was made. It allowed the king to regain some power, but he promised to uphold the Ordinances.

Lancaster still had disagreements with the king, especially about the king's new favorites, Hugh Despenser the younger and his father, Hugh Despenser the elder. In 1322, a full rebellion broke out. It ended with Lancaster's defeat at the Battle of Boroughbridge and his execution in March 1322.

At the parliament in May of the same year, the Ordinances were officially canceled by the Statute of York. However, six clauses were kept. These dealt with things like the royal household's power and the appointment of sheriffs. But any limits on the king's power were clearly removed.

The Ordinances were never reissued. They don't have a lasting place in English legal history like the Magna Carta does. Some people criticize the Ordinances for focusing only on the nobles' role in politics and ignoring the growing importance of the common people. However, the document and the movement behind it showed new political ideas. It stressed that the nobles' agreement had to be obtained in parliament. It was only a matter of time before it was generally accepted that the Commons (representatives of common people) were an important part of parliament.

See also

- History of the British constitution

- Royal Prerogative

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |