History of the constitution of the United Kingdom facts for kids

The constitution of the United Kingdom is like a set of unwritten rules and traditions that guide how the country is governed. Unlike many countries, the UK doesn't have one single document called "the Constitution." Instead, it's made up of many different laws, court decisions, customs, and agreements.

This system grew slowly over many centuries, starting in the Middle Ages. By the 1900s, the British monarchy (the King or Queen) became a constitutional and ceremonial monarchy. This means the monarch has a special role in traditions but doesn't actually rule the country. Instead, Parliament became the main governing body, making laws for everyone.

At first, the different parts of the UK – England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland – had their own separate ways of governing. England gradually became more dominant. Wales was conquered in 1283 and fully brought under English law by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The Kingdom of Ireland was also ruled by the English monarch.

From 1603 to 1707, England and the Kingdom of Scotland shared the same monarch but had separate governments. This was called the Union of the Crowns. In 1707, England and Scotland officially joined to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. Then, in 1801, Great Britain and Ireland united to become the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Even though the UK is a single state where Parliament has the most power, a process called devolution started in the 1900s and 2000s. This gave some self-government back to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Many countries around the world, especially those that were once part of the British Empire, have used parts of the British constitution for their own systems. This includes the United States and countries that use the Westminster parliamentary system. Ideas like the rule of law (everyone must follow the law), parliamentary sovereignty (Parliament is the supreme law-making body), and judicial independence (judges make decisions fairly without outside pressure) all came from the British system.

The British constitution is one of the oldest in the world, going back over a thousand years. It's known for being very stable, able to change over time, having a bicameral legislature (two houses of Parliament), and the idea of responsible government (the government is accountable to Parliament).

Contents

- Early English Government (800-1216)

- Parliamentary Monarchy and Royal Power (1216–1603)

- Stuart Dynasty and the Rise of Parliament (1603–1707)

- Kingdom of Scotland: Its Own Path

- United Kingdom: A New Nation (1707-1900s)

- Social Reform and World Wars (1900s)

- Modern UK: Devolution and Global Role

- Worldwide Influence

- Key Laws and Documents

- Images for kids

Early English Government (800-1216)

Anglo-Saxon Rule: Kings and Councils (800-1066)

In the 800s and 900s, different Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in England joined together under the House of Wessex to form a single Kingdom of England. Kings had a lot of power. They could make laws, create money, collect taxes, raise armies, control trade, and decide how the country dealt with other nations.

The king was advised by a group of "wise men" called a witan. This group included important lords and church leaders. The witan helped the king make laws and was the highest court. Sometimes, if a king was too young or during a crisis, the witan played an even bigger role in government.

The king and his court often traveled around the kingdom. Priests working for the king helped write important documents. Later, an official called the chancellor appeared, who looked after the king's official seal and documents.

England was divided into areas called shires (like counties today) and smaller areas called hundreds. A "shire reeve" or sheriff was in charge of each shire. Sheriffs made sure royal laws were followed, kept the peace, collected taxes, and led the local army.

There were also different types of courts. The king could give churches or powerful landowners the right to run their own courts and collect money from legal cases.

Norman and Angevin Changes (1066–1216)

Norman Government: New Rulers, New Systems

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, the king and his court, called the curia regis, became the center of government. Here, the king received advice, listened to complaints, and settled important legal cases. Sometimes, the king would call a "great council" (magnum concilium) of important nobles and church leaders to discuss big national issues and make laws. These councils helped the king get support for his plans.

Since Norman kings often spent time in Normandy (France), they needed someone to govern England when they were away. The chief justiciar acted as the king's main minister and deputy, especially for money and legal matters. The chancellor continued to oversee royal documents.

During the reign of Henry I, the royal treasury became part of the exchequer. This was the main financial department, named after the checkered cloth used for counting money. The exchequer had a lower part for collecting money and an upper part where officials checked the accounts of sheriffs. It also acted as a court for financial disputes.

Sheriffs still managed the counties, enforcing royal justice and collecting taxes. Courts in the hundreds and counties continued to deal with disputes over land, violence, and theft. The king also sent out traveling judges to hear important cases.

Angevin Government: The Start of Common Law

Henry II, the first Angevin king, introduced new laws called "assizes." These were agreements between the king and his nobles to clarify or change existing customs.

Henry's legal changes were very important. They led to the creation of the common law system and made royal justice more accessible to ordinary people. For example, new procedures helped quickly resolve land disputes. The Assize of Clarendon was a big step towards trial by jury. Traveling judges went around the country, and local juries identified people accused of crimes. At first, guilt was decided by "ordeal" (like walking over hot coals) or "trial by battle," but these were later replaced by jury trials.

As the legal system grew, it became more specialized. Two main courts were set up at Westminster Hall. The Court of Common Pleas handled everyday civil cases like debts and property disputes. The Court of King's Bench dealt with cases involving the king, breaches of peace, and criminal cases. It could also review decisions from the Common Pleas.

Kings needed more money to pay for wars and other expenses. They started asking the great council for permission to collect new taxes. This made the council more important, as it could represent the "community of the realm" and agree to taxes on their behalf. This also led to more disagreements between kings and nobles, as the nobles tried to protect the rights of the king's subjects.

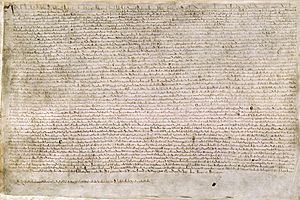

Magna Carta: A Big Step for Rights (1215)

King John needed a lot of money to get back lands he had lost in Europe. He used unfair taxes and fines, which made the nobles very angry. In 1215, about 40 nobles rebelled. A larger group, around 100 nobles, worked with Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, to find a solution. This led to the Magna Carta.

Magna Carta was a document that listed the rights the nobles believed they should have. It was based on three key ideas that were important for the future of the constitution:

- The king had to follow the law.

- The king could only make new laws and raise taxes (except for traditional feudal payments) with the agreement of the community.

- People's obedience to the king was not absolute; it depended on the king following the rules.

Even though a clause about needing "common counsel" for taxation was later removed, kings still generally followed this idea. Magna Carta changed the nobles' duty to advise the king into a right to agree to things. While the nobles created it, the rights in Magna Carta were given to "all the free men of our realm." It did not apply to the majority of the population, who were unfree serfs.

Magna Carta was a starting point. It showed that the king was subject to the law, but the king still had most of the power to make laws. Over time, Magna Carta became a "fundamental statute." The first three clauses have never been removed:

- The English Church should be free and keep its rights.

- The city of London and other cities, towns, and ports should keep their old freedoms.

- Justice should not be sold, denied, or delayed to anyone.

Parliamentary Monarchy and Royal Power (1216–1603)

Parliament's Rise (1216–1399)

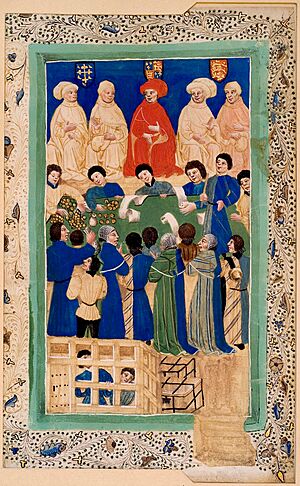

By 1237, the king's court had officially split into two separate groups. The king's council was a smaller, permanent group of ministers and close advisors who managed daily government. Parliament was a larger assembly of important nobles that met only when the king called it. Parliament was seen as representing the "community" and could "talk" with the king and his council.

Parliament became very good at insisting on its right to agree to new taxes. A pattern developed where the king would make promises (like confirming Magna Carta) in exchange for Parliament granting him money. This was Parliament's main way to influence the king. However, kings could still raise money from other sources without Parliament's permission, such as from royal lands or feudal payments.

Barons Push for Reform

The government of Henry III was led by ministers who became very powerful and wealthy. Many nobles were unhappy, especially because the king's closest advisors were often foreigners.

At the Oxford Parliament of 1258, reform-minded nobles forced King Henry to accept a new system called the Provisions of Oxford. These rules aimed to make sure Parliament approved all major government actions. Under these provisions, Parliament officially became the "voice of the community."

Even though the king later defeated the reform party and overturned the Provisions of Oxford, Henry III's reign marked the beginning of a change. The idea started to grow that the king should rule through institutions and needed the trust of his people.

Edward I and Parliament's Growth

During the reign of Edward I, Parliament continued to grow. Edward often called Parliament meetings, usually twice a year. As the feudal system changed, more people became involved in politics. Representatives from shires and towns, called knights of the shire and burgesses, started to attend Parliament.

At this time, the king still largely made laws. Laws made in Parliament were usually just announced by the king or his ministers there. However, important new laws that changed the common law, like the Statute of Westminster 1275, began to be passed.

Edward I conquered Wales in 1283. The Statute of Wales created a system of shires for northern Wales and imposed English criminal law. However, traditional Welsh law continued in other areas. In 1301, the king gave his eldest son the title Prince of Wales.

The Black Death in 1348 killed about a third of England's population. This led to a shortage of workers, and wages rose. The king and Parliament tried to stop this with the Statute of Labourers 1351, which froze wages. This caused the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, where people demanded an end to the feudal system. Even though the revolt was put down violently, it helped break down slavery and serfdom.

Tudor Rule: Strong Kings and a Growing Parliament

Under Henry VIII, the Church of England separated from Rome in 1534, and the King became its head. The Law in Wales Act 1535 officially united Wales and England. Henry VIII was a very powerful king, even executing his Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas More.

After Henry VIII and his son Edward VI died, Elizabeth I became queen in 1558. Her reign was a time of prosperity. A second Act of Supremacy 1559 gave Elizabeth power over the Church of England again. After England defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, Parliament felt more confident.

Parliament had two parts: the House of Lords, made up of powerful nobles and church leaders, and the House of Commons, which included representatives from the aristocracy and the growing middle class. The House of Commons grew in size. Some members, called Puritans, started asking for more rights, which would cause problems for future kings.

Stuart Dynasty and the Rise of Parliament (1603–1707)

Clash Between King and Parliament

When James, who was already King of Scotland, became King of England in 1603, he believed in the "divine right of Kings." This meant he thought his power came directly from God and he didn't have to answer to Parliament. This led to big arguments.

Parliament traditionally voted on the king's taxes, but now they wanted to do it every year to have more control. James I didn't like this and sometimes dissolved Parliament. His son, Charles I, was even more determined to rule without Parliament. He tried to collect taxes, like "Ship Money," without their approval.

A London MP, John Hampden, refused to pay the Ship Money tax and was put on trial. Even though he was convicted, the fact that five out of twelve judges voted against the king showed how much opposition there was.

In 1628, Parliament presented Charles I with the Petition of Right 1628. This document demanded that the king follow Magna Carta, not collect taxes without Parliament's consent, not imprison people unfairly, and not force soldiers into private homes. Charles I signed it because he needed money for wars, but then he ignored it and shut down Parliament again.

English Civil War and Commonwealth

The disagreements led to the English Civil War in 1642. The country was divided between supporters of the King (Cavaliers) and supporters of Parliament (Roundheads). Parliament, with the help of the Scottish and their New Model Army led by Oliver Cromwell, eventually defeated the King.

In 1649, King Charles I was captured and executed. Parliament then abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords, creating a republic called the "Commonwealth." However, it was mostly a dictatorship run by Oliver Cromwell, who became "Lord Protector."

After Cromwell died, the monarchy was brought back in 1660 with Charles II. But his brother, James II, also tried to rule with divine right. In 1688, Parliament "invited" William and Mary of Orange to become King and Queen. This event, known as the Glorious Revolution, forced James II out.

The Bill of Rights 1689 (and the Claim of Right Act 1689 in Scotland) was then passed. This document made Parliament supreme over the monarch. It said that the king could not suspend laws without Parliament's consent, that elections for Parliament should be free, and that Parliament should meet often. This laid the foundation for a constitutional monarchy where the monarch's power is limited by law.

New Ideas and Political Parties

During this time, new ideas about government and rights emerged. Soldiers and groups like the Levellers debated who should have the right to vote. Later, the Royalist and Parliamentarian groups developed into the Tory and Whig political parties.

The Diggers, a smaller group, wanted to dismantle the state and have everything held in common. Their ideas influenced thinkers like John Locke, whose philosophy about protecting people's "lives, liberties, and estates" later influenced the founders of the United States.

Wales: Becoming Part of England

Under the Statute of Wales in 1284, English criminal law replaced Welsh law. Later, Henry VIII's Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 imposed English civil law and formally made Wales a full part of the Kingdom of England.

For a long time, there was no difference between the government of England and Wales. All laws for England included Wales. It wasn't until 1948 that laws started to be specifically for "England and Wales" or "Scotland," giving Wales a separate legal identity again. In 1964, the Welsh Office was created to oversee laws in Wales. This continued until devolution in 1998, which created the self-governing National Assembly for Wales.

Kingdom of Scotland: Its Own Path

Early Scottish Government

From the 400s AD, northern Britain had many small kingdoms. Viking raids helped speed up the joining of Pictish and Gaelic kingdoms. This led to the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín as "king of the Picts" in the 840s, forming the Kingdom of Alba (later Scotland).

The Scottish kings had traditional coronations at the Stone of Scone. While the kings often traveled, places like Scone, Stirling, and Perth were important royal sites before Edinburgh became the capital in the 1400s.

The Scottish Crown was the most important part of government. Like in England, Scotland developed official roles like Lord Chancellor. The King's Council became a full-time body that helped with justice. The Privy Council also played a key role, even after the Scottish monarchs moved to England in 1603.

The Parliament of Scotland also grew into an important legal body, overseeing taxes and policies. It met almost every year, partly because kings were often young or there were regents ruling for them.

United Kingdom: A New Nation (1707-1900s)

Forming Great Britain and Ireland

With Parliament now having supreme power, a new financial system was created, including the Bank of England Act 1694.

The Act of Settlement 1701 made important changes:

- Judges could only be removed by a vote of both Houses of Parliament, not by the king.

- People who held paid jobs for the Crown or received a pension from the Crown could not serve in the House of Commons.

- No Catholic, or spouse of a Catholic, could become King or Queen.

- The King or Queen had to be Anglican.

- The line of succession was set for Protestant relatives.

In 1703, a court case called Ashby v White established that the right to vote was a constitutional right.

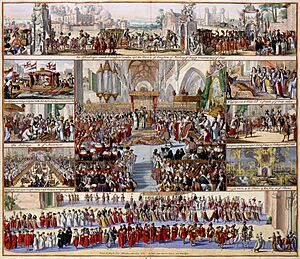

In 1706, Scottish and English representatives began talks for union. The Acts of Union 1707 were passed by both Parliaments, and on May 1, 1707, the two countries officially united as Great Britain. This created a new Parliament of Great Britain. Scotland kept its separate legal system.

Later, in 1801, Great Britain and Ireland joined to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through the Acts of Union 1800.

Political and Industrial Changes

The industrial revolution began, bringing new inventions like the steam engine. But it also led to more poverty. Laws like the Corn Laws (1815) made food expensive to help landowners, which hurt ordinary people.

The Great Reform Act 1832 slightly expanded the right to vote, but only property owners could vote. The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 abolished slavery in the British Empire, but former slaves had to pay off debts for their freedom. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 punished unemployed people by sending them to workhouses.

A movement called Chartism grew, demanding the right to vote for all men in fair elections. In 1848, Chartists held a large march to Parliament as revolutions broke out across Europe.

Gradually, more political freedoms were granted. The Second Reform Act 1867 gave more middle-class property owners the right to vote. The Elementary Education Act 1870 provided free primary school. The Trade Union Act 1871 allowed workers to form unions without being punished. By the Representation of the People Act 1884, about one-third of men could vote.

However, outside the UK, in the vast British Empire, liberty and voting rights were often violently suppressed.

Social Reform and World Wars (1900s)

Votes for All and Irish Independence

From the early 1900s, the UK saw huge social and constitutional changes. The House of Lords (the unelected upper house of Parliament) tried to limit trade union freedom. In response, the Labour movement grew, and in the 1906 election, Labour MPs supported the Liberal Party's reforms. These included:

- A legal guarantee for unions to bargain and strike.

- Old age pensions.

- Minimum wages.

- A "People's Budget" with higher taxes on the wealthy to fund public services.

After the House of Lords tried to block these reforms, the Parliament Act 1911 was passed. This law stopped the House of Lords from blocking legislation for more than two years and removed their power to delay money bills at all.

Despite these reforms, the UK entered World War I. After the war, with millions dead, the Representation of the People Act 1918 gave all adult men the right to vote. It was only after the protests of the Suffragettes that the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 finally gave all women the right to vote, making the UK a full democracy.

The war also led to an uprising in Ireland and the Irish War of Independence. This resulted in the island being divided by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The southern part became the Irish Free State (later the Republic of Ireland), while six northern counties remained part of the UK as Northern Ireland. The UK officially changed its name to "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" in 1927.

Modern UK: Devolution and Global Role

Post-War Changes and Human Rights

After World War II, the United Nations was created, and the UK became a permanent member of the UN Security Council. The British Empire began to shrink as former colonies like India and nations across Africa gained independence.

To prevent future conflicts and human rights abuses, the Council of Europe was formed, leading to the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950. The UK later joined the European Economic Community (which became the European Union) in 1972, aiming for economic integration and social progress.

Under Margaret Thatcher, there were cuts to public services and local government powers. However, some powers were restored with major devolution to Scotland (1998), Northern Ireland (1998), and Wales (2006). The Good Friday Agreement in 1998 brought peace to Northern Ireland after many years of conflict.

The House of Lords Act 1999 reduced the number of hereditary peers (nobles who inherited their seats) in the House of Lords, making it mostly an appointed body.

Important changes to constitutional law continued. The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 changed how Parliament could be dissolved, setting fixed terms of 5 years. However, this act was later repealed in 2022, returning the power to call elections to the Prime Minister.

Devolution and Recent Referendums

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Labour government introduced many constitutional reforms:

- New, elected parliaments or assemblies were created in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

- A directly elected mayor and assembly were created for London.

- The Human Rights Act 1998 brought the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law.

- The Freedom of Information Act 2000 made government decision-making more transparent.

- The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 created the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, ensuring judges are independent.

In 2014, Scotland held a referendum on whether to leave the United Kingdom. Voters decided by 55% to 45% to remain part of the UK. After this, more powers were given to the Scottish Government through the Scotland Act 2016.

In 2016, the UK held a referendum on whether to leave the European Union. 51.9% of voters chose to leave. The UK officially left the EU on January 31, 2020. Before leaving, the Supreme Court ruled that an Act of Parliament was needed for the government to start the process of leaving the EU.

Worldwide Influence

The British constitutional system has had a huge impact on how other countries govern themselves and their legal systems. Ideas like the rule of law, parliamentary sovereignty, and judicial independence spread around the world because of it.

Magna Carta and the Parliament of England influenced the development of democracy and parliaments in the Middle Ages.

In the American colonies, the Bill of Rights 1689 influenced the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights and later the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Bill of Rights. For example, both the British Bill of Rights and the US Constitution prohibit "cruel and unusual punishment."

The modern system of parliament emerged from the Parliament of Great Britain. Many countries that were once part of the British Empire, like Australia, Canada, and India, adopted the Westminster parliamentary system. This system includes a bicameral legislature (two houses of Parliament) and the idea of responsible government (where the government is accountable to Parliament). The Parliament of the United Kingdom is often called the Mother of Parliaments because it has been a model for so many other parliamentary systems.

English common law has also been a template for legal systems in many countries. The British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council still serves as the highest court of appeal for some former colonies.

The UK's constitutional system is one of the oldest in the world, known for its stability and ability to adapt to change over many centuries.

Key Laws and Documents

While there isn't one single list of "constitutional laws," some laws are very important to the history of the UK's constitution.

Scottish Documents and Laws

- Declaration of Arbroath (1320): A declaration sent to the Pope asserting the independence of the Scottish people.

- Claim of Right Act 1689: Limited the power of the Scottish monarch, similar to the English Bill of Rights.

- Union with England Act 1707: Based on the Treaty of Union, it abolished the Scottish Parliament and created the new Parliament of Great Britain.

Welsh Laws

- Statute of Rhuddlan (1284): Imposed English criminal law on Wales.

- Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542: Fully united Wales with the Kingdom of England under a single legal system.

English Laws

- Magna Carta (1215): A charter of liberties, a revised version from 1297 is still technically law today.

- Petition of Right (1628): Prohibited taxation without law and other royal abuses.

- Habeas Corpus Act 1679: Protected people from unlawful imprisonment.

- Bill of Rights 1689: Declared William and Mary as monarchs and established parliamentary sovereignty.

- Act of Settlement 1701: Established the Protestant succession to the Crown.

- Union with Scotland Act 1706: Based on the Treaty of Union, it created the new Parliament of Great Britain.

Laws of Great Britain

- Acts of Union 1800: United the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Laws of the United Kingdom

- Representation of the People Acts (1832 to 1969): Reformed elections and extended the right to vote, leading to parliamentary democracy.

- Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949: Limited the power of the unelected House of Lords to reject bills.

- Government of Ireland Act 1920: Granted autonomy to Ireland, leading to its partition.

- Statute of Westminster 1931: Gave former British dominions (like Canada and Australia) legal independence.

- Life Peerages Act 1958 and House of Lords Act 1999: Reformed the House of Lords, making it mostly appointed rather than hereditary.

- European Communities Act 1972: Allowed European Union laws to have direct effect in the UK (later repealed in 2018).

- Human Rights Act 1998: Made the European Convention on Human Rights part of UK law.

- Scotland Act 1998, Government of Wales Act 1998, Northern Ireland Act 1998: Laws that created devolved parliaments and assemblies.

- Freedom of Information Act 2000: Required public authorities to be transparent about their decisions.

- Constitutional Reform Act 2005: Created the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and guaranteed judicial independence.

- Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011: Introduced fixed 5-year terms for Parliament (later repealed in 2022).

- Succession to the Crown Act 2013: Changed the rules of succession to the throne, ending male preference.

Images for kids

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |