Exchequer of Pleas facts for kids

The Exchequer of Pleas, also known as the Court of Exchequer, was an important court in England and Wales. It handled legal cases based on principles of fairness and common law.

The court started as part of the King's Council (called the curia regis). But in the 1190s, it became an independent court. Over time, another court, the Court of Chancery, became known for being slow and expensive. Because of this, many cases started going to the Exchequer instead.

The Exchequer and the Chancery had similar jobs, so they became very close. But in the 1800s, people started asking why there were two courts doing almost the same thing. Because of this, the Exchequer lost its power to deal with fairness cases. Finally, in 1880, the Exchequer was officially closed down as a court.

The Exchequer's jurisdiction (the types of cases it could hear) changed over time. At first, it handled both common law and fairness cases. But after the Court of Common Pleas was formed, the Exchequer lost much of its common law work. From then on, it mostly dealt with fairness cases and special common law cases. These included cases against its own officials or cases where the king sued people who owed him money.

A special legal order called the `writ of quominus` helped the Exchequer hear many more cases. This order allowed the court to hear regular cases between ordinary people. The Chancellor of the Exchequer was formally in charge, but the actual cases were heard by judges called the Barons of the Exchequer. These judges were led by the Chief Baron. Other important people included the King's Remembrancer, who kept records, and clerks who acted as lawyers.

Contents

History of the Court

How it Started

Some people thought the Exchequer was based on a similar court in Normandy (France). But there is no real proof of this. The first clear records of the Exchequer are from the time of King Henry I. These records show the Exchequer working from the king's palace as part of his council, the curia regis.

The curia regis moved around with the king. It met in places like York, London, and Northampton. But by the late 1100s, the Exchequer started meeting in one fixed place. It was the only part of the government to do this. By the 1170s, you could tell the Exchequer's work apart from other parts of the curia regis. It was called the Curia Regis ad Scaccarium, which means "King's Court at Exchequer". The name "Exchequer" comes from the chequered (checked) cloth used on a table to count money.

In the 1190s, the Exchequer began to separate from the curia regis. This process continued into the early 1200s. Experts believe this happened because there was a growing need to collect money for the king. This led to part of the court's common law work splitting off to form the Court of Common Pleas. Even though the Exchequer of Pleas was the first common law court, it was the last to become fully separate from the king's council.

Growing Work and Changes

We don't have many records from before 1580 because bills were not dated before then. Until the 1500s, the Exchequer did its job without many changes. It was a small court, handling about 250 cases a year. This was much less than the Court of King's Bench (2,500 cases) and the Court of Common Pleas (10,000 cases).

Under the Tudor kings and queens, the Exchequer became more important. This was partly thanks to the Lord High Treasurer. This person was the head of the Exchequer. From 1547 to 1612, powerful figures like Robert Cecil and William Paulet held this job. Their influence made the Exchequer more important too.

However, when the second and third Dukes of Norfolk were Lord High Treasurers (1501-1546), the Exchequer's power actually went down. The government saw these Dukes as too independent. So, to reduce their power indirectly, the Exchequer was deliberately weakened. When William Paulet became Treasurer in 1546, the Exchequer's power grew again. It even took over other courts like the Court of Augmentations.

A skilled clerk named Thomas Fanshawe also helped the Exchequer during this time. He was often asked for advice by the Barons (judges). He helped make court procedures standard, which allowed the Exchequer to handle more cases. His changes were so good that they were used as the standard until the 1830s.

The number of cases in the Exchequer increased under King James I and King Charles I. Then the English Civil War caused problems for the courts. During this time, the use of the Writ of Quominus grew. This writ allowed people who owed money to the king to sue someone else who owed them money. This was because if they got their money back, they could then pay the king. This change helped the Exchequer become a full court for both fairness and common law cases, not just a "tax court."

The Civil War led to four fairness courts closing down. After the war, only two fairness courts were left: the Exchequer and the Court of Chancery. The Court of Chancery was disliked because it was slow and its leader, Lord Chancellor John Finch, was involved in the war. Because of this, the Exchequer became even more important as a court.

Losing Power and Closing Down

By the early 1700s, the Exchequer was a strong court for fairness cases. It was seen as a good choice instead of the Court of Chancery. Both courts even used each other's past cases as examples. Laws passed in the 1700s treated them the same, just calling them "courts of equity" (fairness courts). At the same time, the Treasury became more important, which reduced the Exchequer's influence. Despite these signs, the Exchequer continued to do well and had a lot of business. By 1810, it was almost entirely a fairness court.

In the 1830s, the Exchequer's fairness side became very unpopular. This was because many cases were heard by only one judge, and it was hard to appeal their decisions. While cases could go to the House of Lords, it was very expensive and took a long time. The Court of Chancery, however, had a clear way to appeal cases.

Also, some of the Exchequer's fairness business disappeared. For example, a law in 1836 ended cases about tithes (payments to the church). Another law in 1820 created a special court for bankruptcy, taking those cases away from the Exchequer. The Exchequer's fees were also higher than the Court of Chancery's. Since both courts used similar rules, people felt it was not necessary to have two fairness courts. So, in 1841, a law officially ended the Exchequer's power over fairness cases.

With the loss of its fairness cases, the Exchequer became only a common law court. It then faced the same fate as the other two common law courts: the Court of Queen's Bench and the Court of Common Pleas. For a long time, people had wanted to combine these courts. In 1828, a Member of Parliament named Henry Brougham complained that having three separate courts led to unevenness. He said that people would always choose their favorite court, which would then attract the best lawyers and judges.

In 1867, a group was formed to look into problems with the central courts. This led to the Judicature Acts. These laws combined all the central courts into one big court called the Supreme Court of Judicature. The three common law courts became three parts of this new Supreme Court. This was not meant to be permanent. It was done to avoid having to remove or demote any of the top judges.

By chance, the heads of the Exchequer and King's Bench both died in 1880. This allowed the common law parts of the Supreme Court to be combined into one division, the Queen's Bench Division. This happened on December 16, 1880. At this point, the Exchequer of Pleas officially stopped existing.

What Cases it Heard

The Exchequer's role as a court began from informal talks between the king and people who owed him money. By the 1200s, this had become formal court cases. So, at first, only the king could bring cases to this court. The Exchequer became the first "tax court," where the king was the one suing, and the person who owed money was the defendant. The king was represented by the Attorney General, which saved him legal costs.

The next step was to let people who owed money to the king collect their own debts in the Exchequer. This way, they could pay the king back. This was done using the Writ of Quominus. The Exchequer also had the only power to hear cases against its own officials or people who collected royal money. The court was also used to prosecute religious leaders who were close to breaking a rule. Since the Attorney General represented the king, the costs were lower, and it was more serious for the religious leader. In 1649, the Exchequer officially expanded its power to hear any civil case.

The Exchequer's main job was to collect royal money, which was overseen by the Lord High Treasurer. The Exchequer was special because it handled both fairness and common law cases. Its common law power was limited after the Magna Carta, with those cases going to the King's Bench and Common Pleas. But its common law power grew back later. This was a reversal; in the 1500s, the Exchequer was only a common law court, and its fairness power only became important again near the end of the Tudor period. By 1590, the Exchequer's power over fairness cases was confirmed. It handled many cases each year, including disputes over trusts, mortgages, and tithes. Since taxes were always present, it was easy to show that a dispute prevented someone from paying a debt to the king, which allowed the Writ of Quominus to be used.

The Exchequer was equal to other major courts like the Common Pleas, King's Bench, and Court of Chancery. Cases could be moved easily between them. The Exchequer had a clear rule with the Court of Chancery: a case heard in one could not be heard again in the other. Other than that, fairness cases could be heard by either court. The Exchequer also had higher status than smaller fairness courts. It could take cases from them and change their decisions. The power of religious courts also sometimes overlapped with the Exchequer, especially for collecting tithes. There are many records of arguments between them.

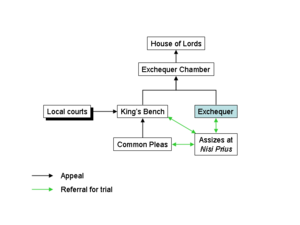

People could appeal cases from the Exchequer to the Exchequer Chamber and also to the House of Lords. The first appeal to the House of Lords happened in 1660.

Court Officials

Treasurer

The formal head of the Exchequer for most of its history was the Lord High Treasurer. This person was in charge of collecting the king's money. At first, the Treasurer was a clerk supervised by the Chief Justiciar. They only became the head of the court after the Chief Justiciar's job was ended by King Henry III. During the time of Queen Elizabeth I, the Treasurer's other duties grew, and they played less of a role in the Exchequer's daily work. By the 1600s, a special Treasurer of the Exchequer took over. This Treasurer, while active in collecting money, did not play a big role in the Exchequer of Pleas court itself.

Chancellor

The Chancellor of the Exchequer was also involved in the Exchequer of Pleas. This person acted as a check on the Lord High Treasurer. The Chancellor started as a clerk to the Lord Chancellor. This clerk sat in the Exchequer and was in charge of checking and sealing legal orders. They also held the Exchequer's copy of the Great Seal. The first records of such a clerk are from 1220.

The Lord Chancellors at that time were often religious leaders who were not very interested in legal or money matters. So, the clerk became more independent. By the 1230s, this clerk was appointed by the king and held the seal on their own. They became known as the Chancellor of the Exchequer. After 1567, the Chancellor also became the Under-Treasurer of the Exchequer. This allowed them to do the Treasurer's job if the Treasurer was not available.

Until the English Civil War, the Chancellor of the Exchequer was a legal job with little political power. But after the war, it became a "stepping stone" to higher political jobs. After 1672, it went back to being a legal and administrative job. Then, in 1714, the Chancellor's role as head of the Treasury made it an important political appointment again.

Barons (Judges)

The main judges were the Barons of the Exchequer. At first, these were the same judges as those in the King's Bench. They only became separate jobs after the Exchequer split from the curia regis. In the early years, the Barons were the chief people who checked England's accounts. This job later went to special auditors.

As the Exchequer grew during the Tudor period, the Barons became more important. Before, only the Chief Baron had to be a Serjeant-at-Law (a senior lawyer). But it became common for all Barons to be Serjeants. This made the Exchequer equal to the Common Pleas and King's Bench, where all judges were already Serjeants.

At least one Baron had to be present to hear a case. Usually, there were no more than four Barons after the time of King Edward IV. This was just a custom, so it was sometimes broken. If a Baron was sick, a fifth one might be appointed. In 1830, a fifth Baron was permanently added to help with too many cases. At the same time, a fifth judge was added to the Common Pleas and King's Bench courts.

The first Baron was called the Chief Baron of the Exchequer. If the Chancellor and Treasurer were not there, he was the head of the court. If he was also absent, the Second Baron took charge, and so on. The Second, Third, and Fourth Barons were called puisne Barons. At first, these were individual jobs, but after the time of King James I, their order was based on how long they had been judges. Unlike in the King's Bench, the different positions did not mean different powers. Each Baron had an equal vote.

Barons were appointed by special documents and sworn in by the Lord Chancellor. During the 1500s, they held their jobs "during good behavior." A Baron could leave if they resigned, died, or were appointed to another court. Their appointment documents expired when a monarch died. When a new monarch was crowned, a Baron had to get a new document or leave their job. This was usually just a routine step.

Remembrancer

The King's Remembrancer was the chief clerk of the Exchequer. They handled all fairness cases. This job was similar to the Master of the Rolls in the Court of Chancery, as they led the clerical side of the court. The King's Remembrancer also handled the money collection side of the Exchequer.

At first, the Remembrancer could appoint all the sworn clerks. But by the 1500s, this power was limited to appointing only one of the 24 side clerks. The sworn clerks appointed the rest. Similarly, while they were once in charge of the court's records, by the 1600s, they no longer had the keys to the record office. The sworn clerks had the only right to search the records. The Remembrancer's main job became more like a judge, examining witnesses and settling disputes.

The Remembrancer was appointed for life and could appoint a deputy. From 1565 to 1716, the job stayed in the Fanshawe family. After 1820, the Remembrancer's many duties were split up. Two masters were appointed to replace him. One of them was the accountant general. These officials were appointed by the Chief Baron of the Exchequer and held their jobs "during good behavior." They could not appoint a deputy. The masters took minutes in court, and the accountant general oversaw all money paid into the court. This money was deposited in the Bank of England. Before, the Remembrancer had full control over the money.

Other Jobs

Other jobs included the sworn clerks, examiners, clerks to the barons, and the clerk to the King's Remembrancer. There were eight sworn clerks. They held their jobs for life and worked under the Remembrancer. Each sworn clerk acted as a lawyer for parties in court, and every party had to hire one. The first clerk was called the First Secondary.

The sworn clerks were helped by 24 side clerks. Each sworn clerk appointed three side clerks. A side clerk studied under a sworn clerk for five years before they could practice. A side clerk could be promoted to a sworn clerk.

The examiners were in charge of watching witnesses give their statements. They would bring the witness to a Baron, give them an oath, and keep the records of the statements. In 1624, it was decided that these examiners should be sworn officers of the court. From then on, each Baron had an examiner who acted in the Baron's name. The job of examiner ended in 1841 when the Exchequer lost its fairness cases.

Besides an examiner, each Baron had at least one clerk. These clerks acted as private secretaries. They were not paid a salary but could take fees for their work. The Chief Baron had two clerks, while the other Barons had one each. The King's Remembrancer also had a clerk who was a secretary. This clerk did not get a salary and was not a sworn officer, meaning the Remembrancer could replace them at any time.

See also

- Court of equity

- Baron of the Exchequer

- Chief Baron of the Exchequer

- Court of Exchequer (Scotland)

- Exchequer of Ireland

- List of Lord High Treasurers

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |