Parsis facts for kids

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India | 69,000 (2014) |

| Pakistan | 1,092 (2016) |

| Languages | |

| English (Indian dialect or Pakistani dialect), Gujarati, and Hindi–Urdu | |

| Religion | |

| Zoroastrianism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Iranis | |

Parsis are a special group of people in India and Pakistan. They follow an ancient religion called Zoroastrianism. Their ancestors came from Persia (modern-day Iran) many centuries ago.

They left Persia to keep their Zoroastrian faith alive after the Arab conquest. They settled in Medieval India, mostly in the state of Gujarat. The word Parsi means "Persian" in the Persian language.

There are two main groups of Zoroastrians in India. Parsis are the older group. The other group, called Iranis, came later from Iran. Both groups share the same religious beliefs and customs.

Who Are the Parsis?

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Parsis are followers of the prophet Zoroaster from Persia. They moved to India to escape religious difficulties from Muslims. Most Parsis live in Mumbai and other towns in southern Mumbai. Some also live in Karachi (Pakistan) and Chennai.

They are not part of the Hindu caste system, but they form their own clear community. No one knows the exact date the Parsis arrived in India. Some believe it was in the 8th century, while others think it was as late as the 10th century. They first settled in Diu and then moved to South Gujarat. There, they lived as a small farming community for about 800 years.

The name Parsi means "person from Pārs" (a region in Persia). This term was not often used in Parsi texts in India until the 17th century. Before that, they called themselves Zartoshti (Zoroastrian) or Vehdin (of the good religion). The earliest known use of "Parsi" for Indian Zoroastrians is from a 12th-century text called Sixteen Shlokas.

The first time Europeans wrote about Parsis was in 1322. A French monk named Jordanus mentioned them in Thane and Bharuch. Later, many European travelers used a European version of the local name for them. For example, a Portuguese doctor in 1563 called them "Esparcis."

Parsi Identity and Community

Over many centuries, Parsis have become part of Indian society. But they have also kept their own special customs and traditions. This means they are mostly Indian in terms of their country, language, and history. However, they are different in their family background, culture, and religious practices.

Some people believe that Parsis, like Ashkenazi Jewish people, might have a higher average intelligence. This is thought to be because of their achievements in many fields and their high education levels. More research is needed to understand why this might be.

What Makes Someone a Parsi?

It can be tricky to decide who is a Parsi. Generally, a Parsi is someone who:

- Is a direct descendant of the first Persian refugees.

- Has been officially welcomed into the Zoroastrian religion through a ceremony called navjote.

So, "Parsi" describes both a family background and a religion. There is some debate within the community about this. Some believe a child must have a Parsi father to join the faith. However, many people think this goes against the Zoroastrian idea of gender equality. They also believe it might be an old rule that is no longer fair.

An old legal rule from 1909 said that a person could not become a Parsi by changing their religion. It also stated that the Parsi community included:

- Parsis descended from the first Persian immigrants, born to two Zoroastrian parents, and who follow the Zoroastrian religion.

- Iranis (meaning people from Iran, not the other Indian Zoroastrian group) who follow the Zoroastrian religion.

- Children of Parsi fathers and non-Parsi mothers who were properly welcomed into the religion.

This rule has been changed many times. The Indian Constitution says everyone is equal, so the rule about only Parsi fathers is not valid. The part about Iranis was also changed. Today, some Parsis believe that for a child to join the faith, both parents should be Parsi.

Parsi Population

The number of Parsis in India has been decreasing. In 2011, there were 57,264 Parsis in India. This decline is due to several reasons, including fewer children being born and people moving away. Experts believe that by 2020, the Parsi population might be as low as 23,000. If the numbers continue to drop, Parsis might be called a 'tribe' instead of a community.

About one-fifth of the population decrease is because Parsis move to other countries. There are Parsi communities in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and the United States. More Parsis are dying than are being born. In 2001, 31% of the community was over 60 years old. Only 4.7% were under 6 years old. This means only about 7 babies are born each year for every 1000 Parsis.

Some Parsis have also moved back to Iran, their ancient homeland. While their numbers are small, they help strengthen the connection between Iranian and Indian Zoroastrians. Parsis played a big part in making Iran more modern in the 20th century. They reminded Iranians of their old heritage. They also showed that it was possible to be modern while keeping their original culture.

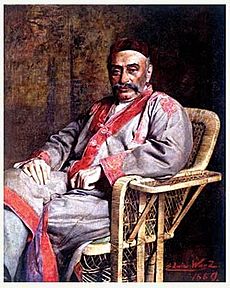

The leaders of Iran, Reza Shah and Muhammad Reza Shah, encouraged Parsis to invest in Iran. They invited them to return and help the country grow. In 1932, Reza Shah invited Dinshah Irani, a Parsi leader, to visit Iran. The Shah told the Parsis that Iran was their home too and they should help develop it.

Other Facts About Parsis

The number of males and females among Parsis is unusual. In 2001, there were 1000 males for every 1050 females. This is mainly because many elderly women live longer than elderly men. The average in India was 1000 males for every 933 females.

Parsis have a very high literacy rate. In 2001, 97.9% of Parsis could read and write. This was the highest among all Indian communities. The national average was 64.8%. Most Parsis (96.1%) live in urban areas. Their main language is Gujarati.

In Mumbai, where many Parsis live, about 10% of Parsi women and 20% of Parsi men do not marry.

Parsi History

Arrival in India

The Qissa-i Sanjan is the only story about the early years of Zoroastrian refugees in India. It was written at least six centuries after they arrived. It says the first group of immigrants came from Greater Khorasan, a region in northeastern Iran and parts of Central Asia.

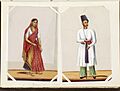

According to the Qissa, a local ruler named Jadi Rana allowed the immigrants to stay. But they had to agree to three conditions:

- Speak the local language (Gujarati).

- Their women had to wear local clothes (the sari).

- They could not carry any weapons.

The refugees agreed and built a settlement called Sanjan. They named it after their original city in Persia. A second group from Khorasan followed within five years, bringing religious items with them.

Historians are not sure about the exact date the Parsis arrived. The Qissa is not very clear about the dates. Possible arrival years are 716, 765, or 936. The Qissa is important because it shows how Parsis see themselves and their relationship with Indian culture.

The Sanjan Zoroastrians were probably not the first Zoroastrians in India. The Sasanian Empire had outposts in Sindh, which is now part of Pakistan. Even after losing Sindh, Iranians were important in trade between the East and West. An Arab historian in the 9th century mentioned Zoroastrians with fire temples in India. There is also proof of individual Parsis living in Sindh in the 10th and 12th centuries.

Parsi stories say their ancestors were religious refugees who fled Persia after the Muslim conquests. They wanted to keep their ancient faith. However, it is not certain that they migrated only because of religious difficulties. If they arrived in the 8th century, Zoroastrianism was still the main religion in Iran. So, economic reasons might have also played a part in their decision to move.

Early Years in India

The Qissa does not say much about what happened after Sanjan was built. It only mentions the creation of the "Fire of Victory" (Atash Bahram) at Sanjan and its later move to Navsari. According to Dhalla, the next few centuries were "full of hardships" before Zoroastrianism became strong in India.

Two centuries after arriving, Parsis started settling in other parts of Gujarat. This caused problems about which priest had authority over which area. By 1290, Gujarat was divided into five panthaks (districts). Each district was led by one priestly family. Later, arguments about the Atash Bahram led to the fire being moved to Udvada in 1742. Today, the five priestly families take turns caring for it.

Old writings found in the Kanheri Caves near Mumbai show that until the early 11th century, Middle Persian was still the language used by Parsi priests for religious texts. There is not much information about Parsis between the 11th and 12th centuries. But in the 12th and 13th centuries, excellent Sanskrit translations of their holy book, the Avesta, were made. This suggests that religious studies were very important at that time.

From the 13th to the late 16th century, Parsi priests in Gujarat sent 22 requests for religious advice to Zoroastrians in Iran. They believed Iranian Zoroastrians knew more about religious matters. These letters and their replies, called rivayats, cover the years 1478–1766. They discuss both religious and social topics. Some questions seem small, like whether ink made by a non-Zoroastrian can be used for copying Avestan texts. But they show the Parsis' fears about losing their identity. They also asked about non-Zoroastrians converting to their faith. The answer was that it was acceptable and even good.

However, because they lived in a difficult situation for a long time, Parsis stopped trying to convert others. They feared losing their identity and being absorbed into the large Indian population. Living among the Hindu caste system, they felt they needed to create strict rules to protect their community. They also changed their social structure. They kept only the hereditary priesthood. The other groups (nobles, soldiers, farmers, artisans) became one group called behdini. This change allowed more people to marry each other, which was rare before. It also removed job-based divisions, which the British liked because it made Parsis easier to work with than other Indian groups.

The Age of Opportunity

In the early 17th century, the East India Company gained rights to live and build factories in Surat. Many Parsis, who were farmers in Gujarat, moved to these English settlements for new jobs. In 1668, the East India Company rented the Seven Islands of Bombay from Charles II of England. They found the deep harbor perfect for their first port. Parsis followed and soon got important jobs in government and public works.

Before, only priests could read and write. But during the British Raj, British schools in India gave Parsi youth a chance to get an education. They learned to read, write, and understand British ways. This was very helpful for Parsis. They were able to present themselves as being similar to the British. While the British often saw other Indians as passive or ignorant, they saw Parsis as "diligent," "conscientious," and "skillful" in business.

One important Parsi was Rustom Maneck. In 1702, he became the first broker for the East India Company. He and other Parsis helped expand business and financial opportunities for the Parsi community. By the mid-18th century, most brokerage firms in Bombay Presidency were run by Parsis. Many Parsis became wealthy merchants and ship owners. They were seen as active, careful, and hardworking. In the 18th century, Parsis used their skills in shipbuilding and trade to benefit from trade between India and China. This trade mainly involved timber, silk, and cotton.

Wealthy Parsi families like Sorabji, Modi, Cama, Wadia, Jeejeebhoy, Readymoney, Dadyseth, Petit, Patel, Mehta, Allbless, and Tata became famous. Many of them were known for their involvement in public life and for their educational, industrial, and charity work.

Rustom Maneck's generosity helped Parsis settle in Bombay. He made Bombay the main center for Parsis in the 1720s. When Surat faced political and economic problems, many Parsi families moved to Bombay. By the mid-18th century, Parsis were one of the most important business groups in Bombay. Maneck's charity was also the first recorded example of Parsi giving. In 1689, a chaplain reported that Parsis in Surat helped the poor and needy. They made sure no one in their community was without help.

In 1728, Rustom's son, Naoroz, started the Bombay Parsi Panchayet. This group helped new Parsis with religious, social, legal, and financial matters. The Maneck Seth family used their wealth and time to help the Parsi community. By the mid-18th century, the Panchayet was the accepted way to manage community affairs. However, by 1838, the Panchayet was criticized for unfairness. In 1855, the Bombay Times said the Panchayet had no power to enforce its rules. It soon stopped being seen as representing the community. After a court ruling in 1856, the Panchayet became mainly a "Parsi Matrimonial Court." It was later re-established to manage community property but no longer governed the community.

As the Panchayet's role declined, other organizations emerged. By the mid-19th century, Parsis realized their numbers were falling. They saw education as a solution. In 1842, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy created the Parsi Benevolent Fund to help poor Parsis get an education. In 1849, Parsis opened their first school. The education movement grew quickly. Many Parsi schools were built, and Parsis also attended other schools and colleges.

With better education and stronger community ties, Parsis felt more distinct. In 1854, Dinshaw Maneckji Petit started the Persian Zoroastrian Amelioration Fund. Its goal was to help less fortunate Zoroastrians in Iran. The fund encouraged some Iranian Zoroastrians to move to India. Its efforts also helped get rid of the jizya tax for Zoroastrians in Iran in 1882.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Parsis became "the most important people in India" in education, industry, and social matters. They were leaders in progress, earned huge fortunes, and gave large amounts to charity. By the end of the 19th century, there were 85,397 Parsis in colonial India. About 48,507 lived in Bombay, making up about 6.7% of the city's population in 1881. This was the last time Parsis were a large minority in the city.

The 19th century gave Parsis a strong sense of community. Their unique cultural symbols, like their special Gujarati dialect, arts, and clothing, grew into Parsi theater, literature, newspapers, and schools. Parsis also ran their own medical centers, ambulance services, Scouting groups, clubs, and Masonic Lodges. They had their own charities, housing, legal systems, and governance. They were no longer just weavers and small merchants. They now owned and ran banks, factories, heavy industries, shipyards, and shipping companies.

Even while keeping their own culture, they saw themselves as Indian. Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Asian in the British Parliament, said: "Whether I am a Hindu, a Mohammedan, a Parsi, a Christian, or of any other creed, I am above all an Indian." Parsis played a big role in the Indian independence movement. Most Parsis were against the partition of India.

Parsi Religious Practices

The main parts of Zoroastrianism for Parsis include ideas of purity and pollution, initiation (navjot), daily prayers, worship at Fire Temples, marriage, funerals, and general worship.

Purity and Pollution

The idea of good and evil is linked to purity and pollution. Purity is seen as being very close to God. Pollution aims to destroy purity through death. Parsis believe it is their duty to keep their bodies pure, as God created them. A Zoroastrian priest dedicates his life to living a holy life.

Zoroastrians are not baptized as babies. A child is welcomed into the faith when they are old enough to understand. The child needs to say some prayers with the priest during the Navjote ceremony. This usually happens before they become teenagers. While there is no exact age, it is usually after 7 years old. Navjote cannot be done for adults in the Parsi community, except for descendants of Parsis who want to join the faith. However, Iranian Zoroastrians can have their similar ceremony, called sedreh-pushti, at any age.

The ceremony starts with a special bath and a spiritual cleansing prayer. The child then changes into white pajama pants, a shawl, and a small cap. After some opening prayers, the child receives sacred items: a special shirt (sudre) and a cord (kusti). The child then faces the main priest, and fire is brought in to represent God. Once the priest finishes the prayers, the child's initiation is complete. They have become a part of the community and religion.

Marriage Customs

Marriage is very important to Parsis. They believe it helps continue God's kingdom by having children. Until the mid-19th century, child marriages were common, even though their religion did not require it. When social reforms happened in India, the Parsi community stopped this practice.

However, there are now fewer brides available. More Parsi women are getting good educations. This means they are either getting married later or not at all. In the Parsi community in India, 97% of women can read and write. 42% have finished high school or college, and 29% have jobs where they earn a good amount of money.

The wedding ceremony starts like the initiation, with a cleansing bath. The bride and groom travel to the wedding in cars decorated with flowers. Priests from both families lead the wedding. The couple first face each other with a sheet between them. Wool is passed over them seven times to connect them. Then, they throw rice at each other, which symbolizes who will be in charge. The religious part comes next when they sit side by side to face the priest.

Funeral Traditions

Death is seen as causing pollution, so it must be handled carefully. A separate part of the home is used for the body before it is taken away. The priest says prayers to cleanse sins and confirm the faith of the person who died. Fire is brought into the room, and prayers begin. The body is washed and dressed in a clean sudre and kusti. A circle is drawn around the body, and only the people carrying it can enter.

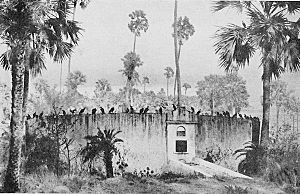

As they go to the cemetery, they walk in pairs, connected by white fabric. A dog is important in the funeral because it is believed to see death. The body is taken to a special place called a Tower of Silence. There, vultures eat the body. Once the bones are bleached by the sun, they are pushed into a central opening. The mourning period lasts four days. Instead of graves, charities are often set up in honor of the person who died.

Fire Temples

Zoroastrian festivals were originally held outdoors. Temples became common later. Most temples were built by wealthy Parsis who wanted places to keep purity. Fire represents the presence of Ahura Mazda (God). There are two main types of fire temples:

- Atash Behram: This is the highest level of fire. The fire is prepared for a whole year before it is placed in the temple. Once there, it is cared for with the greatest respect. There are only eight such temples in India.

- Dar-i Mihr: This is the second type of fire temple. The preparation process for its fire is not as long. There are about 160 of these temples across India.

Different Groups Within the Parsi Community

Calendar Differences

Until about the 12th century, all Zoroastrians used the same 365-day religious calendar. This calendar did not add extra days for the fractional parts of a year. So, over time, it no longer matched the seasons.

Sometime between 1125 and 1250, Parsis added an extra month to their calendar to fix this. However, Parsis were the only Zoroastrians to do this, and they did it only once. This caused their calendar to be 30 days different from the calendar used by Zoroastrians elsewhere. Both calendars were still called Shahenshahi (imperial), because no one realized they were different.

In 1745, Parsis in Surat switched to the Kadmi calendar. Their priests believed that the calendar used in their ancient homeland must be correct. They also thought the Shahenshahi calendar was too "royalist."

In 1906, people tried to bring the two groups together. They introduced a third calendar called Fasili or Fasli. This calendar added a leap day every four years, and its New Year's Day was on the first day of spring. This was the only calendar that always matched the seasons. However, most Parsis did not accept it. They felt it did not follow Zoroastrian traditions.

Today, most Parsis follow the Parsi version of the Shahenshahi calendar. The Kadmi calendar is still used by some Parsi communities in Surat and Bharuch. The Fasli calendar is not very popular among Parsis. But it is used by Zoroastrians in Iran because it matches their Bastani calendar.

Impact of Calendar Debates

Some Avesta prayers mention the names of months, and some prayers are only used at specific times of the year. So, the question of which calendar is "correct" also has religious importance.

To make things more complicated, in the late 18th or early 19th century, a very important priest named Phiroze Kaus Dastur believed that the way Iranians said prayers was correct, but the Parsi way was not. He changed some prayers, and these changes were accepted by all Kadmi calendar followers. However, language experts say that the Iranian pronunciation is actually newer than the Parsi one.

The calendar arguments were sometimes very heated. In the 1780s, feelings were so strong that violence sometimes broke out.

Of the eight Atash-Behrams (the highest fire temples) in India, three follow the Kadmi pronunciation and calendar. The other five are Shahenshahi. The Fassalis do not have their own Atash-Behram.

Ilm-e-Kshnoom Philosophy

The Ilm-e-Kshnoom is a Parsi-Zoroastrian philosophy. It understands religious texts in a mystical and hidden way, not just literally. Its followers believe they are practicing Zoroastrianism as kept by a group of 2000 people called the Saheb-e-Dilan (Masters of the Heart). These people are said to live hidden away in the mountains of the Caucasus or Alborz ranges.

It is not always obvious if a Parsi follows Kshnoom. Their Kusti prayers are similar to those of the Fassalis. Like other Parsis, Kshnoom followers use different calendars. They also have small differences in how they say prayers. However, Kshnoom followers are very traditional in their beliefs and prefer to stay separate even from other Parsis.

The largest group of Kshnoom followers lives in Jogeshwari, a suburb of Mumbai. They have their own fire temple, housing area, and newspaper. A smaller group lives in Surat, where this philosophy started in the late 19th century.

Issues with the Deceased

In Mumbai and Karachi, it has been traditional for dead Parsis to be taken to the Towers of Silence. There, vultures quickly eat the bodies. This practice is because earth, fire, and water are considered sacred. They should not be made unclean by the dead. So, burying or burning bodies has always been forbidden in Parsi culture.

However, in modern Mumbai and Karachi, the number of vultures has greatly decreased. This is due to city growth and medicines given to humans and animals that harm vultures. Because of this, bodies now take much longer to decompose. Solar panels have been put in the Towers of Silence to speed up the process, but this only works partly, especially during monsoons. In Peshawar, a Parsi graveyard was started in the late 19th century, which still exists. This cemetery is unique because it does not have a Tower of Silence. Still, most Parsis continue to use the traditional method for their loved ones. They see it as the last act of charity by the person who died.

The Tower of Silence in Mumbai is at Doongerwadi on Malabar Hill. In Karachi, it is in Parsi Colony, near Chanesar Goth and Mehmoodabad.

Parsi Genetics

Genetic tests have been done to understand Parsi ancestry. Some studies support the idea that Parsis have kept their Persian roots by not marrying people from local populations. A 2002 study of male (Y-chromosome) DNA of Parsis in Pakistan found that Parsis are genetically closer to Iranians than to their neighbors.

A 2004 study compared female (mitochondrial) DNA of Parsis with Iranians and Gujaratis. It found that some Parsi female DNA was genetically closer to Gujaratis than to Iranians. Combining this with the 2002 study, researchers suggested that Parsi ancestors were mostly men who migrated. They then mixed with local women, which led to the loss of Iranian female DNA.

These results were updated in 2017. A new study found that Parsis are genetically more similar to ancient Iranians from the Neolithic period than to modern Iranians. Modern Iranians have mixed more recently with people from the Near East. The study also found that 48% of ancient Parsi samples had South-Asian-specific female DNA. This could be from local women joining the community when Parsis first settled. It might also be from female DNA that no longer exists in Iran. This suggests that Parsis are about three-quarters Iranian and one-quarter Indian genetically.

Genetic studies of Parsis in Pakistan show a big difference between male and female DNA data. This is unusual compared to most populations. Historical records say Parsis moved from Iran to Gujarat, India, and then to Mumbai and Karachi, Pakistan. Their male DNA matches the Iranian population, supporting these records. But when comparing female DNA to Iranians and Gujaratis, it is different from the male DNA. About 60% of their female gene pool comes from South Asian groups. This is only 7% in Iranians. Parsis have a high amount of haplogroup M (55%), similar to Indians, but only 1.7% in Iranians.

Despite their small population, the wide variety in both male and female DNA suggests that there has not been a strong genetic drift. The studies suggest that Parsi male ancestors migrated from Iran to Gujarat. There, they mixed with local women during their first settlements. This mixing eventually led to the loss of Iranian female DNA.

A study published in Genome Biology used detailed genetic data. It showed that Parsis are genetically closer to Iranian populations than to their South Asian neighbors. They also share the most genetic patterns with present-day Iranians. The mixing of Parsis with Indian populations is thought to have happened about 1,200 years ago. It was also found that Parsis are genetically closer to Neolithic Iranians than to modern Iranians.

Parsis have very few DNA changes linked to lung cancer. This points to the community's unique non-smoking habits, which have been practiced for thousands of years. Parsis also tend to live a long time, which is a genetic trait. However, Parsis have been shown to have high rates of breast cancer, bladder cancer, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and Parkinson's disease.

Famous Parsis

Parsis have made huge contributions to India's history and development. This is amazing given their small numbers. As the saying goes, "Parsi, thy name is charity." Their most important contribution is their philanthropy (giving to charity).

The name Parsi comes from the Persian word for a Persian person. But in Sanskrit, it means "one who gives alms." Mahatma Gandhi once said, "I am proud of my country, India, for having produced the splendid Zoroastrian stock, in numbers beneath contempt, but in charity and philanthropy perhaps unequaled and certainly unsurpassed."

Several famous places in Mumbai are named after Parsis, like Nariman Point. Malabar Hill in Mumbai is home to many important Parsis. Parsis who were important in the Indian independence movement include Pherozeshah Mehta, Dadabhai Naoroji, and Bhikaiji Cama.

Famous Parsis in science and industry include:

- Physicist Homi J. Bhabha

- Nuclear scientist Homi N. Sethna

- Industrialists J. R. D. Tata and Jamsetji Tata, who is called the "Father of Indian Industry"

- Construction tycoon Pallonji Mistry

The Godrej, Mistry, Tata, Petit, Cowasjee, Poonawalla, and Wadia families are important Parsi industrial families.

Other notable Parsi business people include Ratan Tata, Cyrus Mistry, Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, Ness Wadia, Neville Wadia, Jehangir Wadia, and Nusli Wadia. Many of them are related through marriage to Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Mohammad Ali Jinnah's wife, Rattanbai Petit, came from the Parsi Petit and Tata families. Their daughter, Dina Jinnah, married Parsi industrialist Neville Wadia. Feroze Gandhi, the husband of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and son-in-law of Jawaharlal Nehru, was a Parsi from Bharuch.

The Parsi community has also given India many distinguished military officers:

- Field Marshal Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw, who led India to victory in the 1971 war, was the first officer of the Indian Army to become a Field Marshal.

- Admiral Jal Cursetji was the first Parsi to be Chief of the Naval Staff of the Indian Navy.

- Air Marshal Aspy Engineer was India's second Chief of Air Staff after independence.

- Air Chief Marshal Fali Homi Major was the 18th Chief of Air Staff.

- Vice Admiral RF Contractor was the 17th Chief of the Indian Coast Guard.

- Lieutenant Colonel Ardeshir Burjorji Tarapore died in the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war and was given the Param Vir Chakra, India's highest military award for bravery.

Other notable Parsis in different fields include:

- Cricketers Farokh Engineer, Nari Contractor, and Polly Umrigar

- Rock musician Freddie Mercury

- Composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

- Conductor Zubin Mehta

- Cultural studies expert Homi K. Bhabha

- Screenwriter and photographer Sooni Taraporevala

- Authors Rohinton Mistry, Firdaus Kanga, Bapsi Sidhwa, and Ardashir Vakil

- Investigative journalists Ardeshir Cowasjee, Russi Karanjia, and Behram Contractor

- Actor Boman Irani

- Educator Jamshed Bharucha

- India's first woman photo-journalist Homai Vyarawalla

- Actresses Nina Wadia and Persis Khambatta, who are known for their work in Bollywood films and TV shows.

- Naxalite leader and intellectual Kobad Ghandy

- Mithan Jamshed Lam was a suffragist, the first female lawyer at the Bombay High Court, and served as a Sheriff of Bombay.

- Dorab Patel was Pakistan's first Parsi Supreme Court Justice.

- Fali S Nariman and Nani Ardeshir Palkhivala are famous legal experts.

- Soli Sorabjee was a prominent Indian lawyer and former Attorney-General of India.

- Rattana Pestonji was a Parsi living in Thailand who helped develop Thai cinema.

- Indian-born American actor Erick Avari, known for his roles in science-fiction films and TV.

- Cyrus S. Poonawalla and Adar Poonawalla are important Indian Parsi businessmen.

Images for kids

-

Map of the Sasanian Empire and its surrounding regions on the eve of the Muslim conquest of Persia

-

"Parsis of Bombay" a wood engraving, ca. 1878

See also

In Spanish: Parsi para niños

In Spanish: Parsi para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |