Homi J. Bhabha facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Homi J. Bhabha

FNI, FASc, FRS

|

|

|---|---|

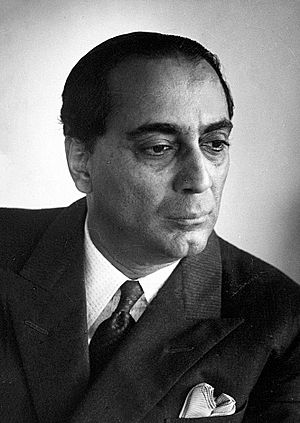

Bhabha c. 1960s

|

|

| Chairperson of the Atomic Energy Commission of India | |

| In office 1948–1966 |

|

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Vikram Sarabhai |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 October 1909 Bombay, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 24 January 1966 (aged 56) Mont Blanc massif |

| Cause of death | Air India Flight 101 crash |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge (BS, PhD) |

| Known for |

|

| Awards | Adams Prize (1942) Padma Bhushan (1954) Fellow of the Royal Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Nuclear physics |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral advisor | Ralph H. Fowler |

| Other academic advisors | Paul Dirac |

Homi Jehangir Bhabha (born October 30, 1909 – died January 24, 1966) was a brilliant Indian nuclear physicist. Many people call him the "father of the Indian nuclear programme". He helped India become a leader in atomic energy.

Bhabha was the first director and physics professor at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). He also founded the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay (AEET). This place was later renamed the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in his honor. Both TIFR and AEET were key to India's nuclear energy plans.

He was also the first chairman of the Indian Atomic Energy Commission. He played a big part in starting the Indian space program. This happened by supporting space science projects that first got money from the Atomic Energy Commission.

Bhabha received important awards like the Adams Prize (1942) and the Padma Bhushan (1954). He was also nominated for the Nobel Prize for Physics several times. Sadly, he died in a plane crash in 1966 when he was 56 years old.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Childhood and Interests

Homi Jehangir Bhabha was born on October 30, 1909, into a well-known and wealthy family in Bombay. His father, Jehangir Hormusji Bhabha, was a famous lawyer. His mother was Meherbai Framji Panday.

From a young age, Homi loved music, painting, and gardening. He enjoyed listening to classical music with his family. He also took special lessons for the violin and piano.

Homi was also a talented artist. When he was seventeen, a self-portrait he painted won second place at a big art show in Bombay. He loved gardening and knew a lot about different plants and flowers.

Even as a child, Homi showed a strong interest in science. He liked to build his own models with Meccano sets. By the time he was fifteen, he was already studying advanced physics ideas like general relativity.

Homi often visited his uncle, Dorabji Tata, who led the huge Tata Group. There, he heard important talks between his uncle and leaders like Mahatma Gandhi. These conversations might have inspired him to become a leader in science.

University Studies in India and Cambridge

Homi finished his early studies with honors at fifteen. He was too young to study abroad, so he first went to Elphinstone College in India. Then, in 1927, he attended the Royal Institute of Science. There, he heard a lecture by Arthur Compton, a Nobel Prize winner. This lecture introduced him to cosmic rays, which became a big part of his future research.

The next year, Homi went to Cambridge University in England. His father and uncle wanted him to study mechanical engineering. They hoped he would return to India and work in the Tata Steel factories.

However, Homi soon realized that engineering was not for him. He wrote to his father, explaining his passion for physics. He believed he was "born and destined to do" physics. His father agreed to let him study mathematics if he did well in his engineering exams. Homi passed both his engineering and mathematics exams with top honors.

At Cambridge, Homi also enjoyed other activities. He designed covers for his college magazine and sets for plays. He even thought about becoming a professional artist. But seeing the exciting work at the Cavendish Laboratory made him focus on theoretical physics. He officially changed his name to Homi Jehangir Bhabha and dedicated himself to science.

Early Research in Nuclear Physics

Homi Bhabha worked at the Cavendish Laboratory while studying for his PhD in theoretical physics. This lab was a hub for new discoveries in physics. Scientists there had found the neutron and learned how to change one element into another. They also used cloud chambers to study tiny particles.

Between 1931 and 1933, Bhabha traveled to famous physics centers in Europe. He visited Niels Bohr's institute in Copenhagen, a key place for theoretical physics. In Zurich, he wrote his first scientific paper with Wolfgang Pauli. He also worked with Enrico Fermi in Rome.

In 1932, the positron was discovered, and a new field called high-energy physics began. Bhabha decided to focus his career on this area. He wrote over fifty papers on the topic. He also played a big role in developing quantum electrodynamics, which explains how light and matter interact.

Bhabha earned his doctorate in nuclear physics in 1935. His thesis was about cosmic radiation and how particles are created and destroyed.

In 1935, Bhabha published a paper where he calculated how electrons and positrons scatter off each other. This process is now called Bhabha scattering in his honor.

In 1937, Bhabha and Walter Heitler wrote an important paper. They explained how cosmic rays from space create showers of particles when they hit Earth's atmosphere. Their calculations matched what scientists had observed. They also suggested that these cosmic rays contained "heavy electrons," which we now know as muons.

Bhabha realized that these "heavy electrons" were the same particles that Hideki Yukawa had described in his theory of the meson. Bhabha suggested calling them "mesons." He also believed that studying mesons could help prove Albert Einstein's theory of relativity and its idea of time dilation.

Career in India

Indian Institute of Science

When World War II started in 1939, Homi Bhabha was on vacation in India. The war made it impossible for him to return to the UK. So, he took a job as a physics reader at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru. This institute was led by C. V. Raman, a Nobel Prize winner.

In 1941, Bhabha became a Fellow of the Royal Society, a very high honor. The next year, he was the first Indian to win the Adams Prize. C.V. Raman called the 32-year-old Bhabha "the modern equivalent of Leonardo da Vinci."

At first, Bhabha thought his time in India was temporary. He hoped to return to Europe or America after the war. However, during his time in Bengaluru, he grew to appreciate Indian culture and art. By 1944, he decided he wanted to stay in India. He felt it was his duty to help his own country, as long as he had the right support.

Tata Institute of Fundamental Research

In 1943, Bhabha suggested creating a new research institute to J. R. D. Tata, a famous industrialist. Tata was interested, as promoting science was a goal of the Tata Trusts.

Bhabha wanted to create a place where many great scientists could work together. He hoped it would be like the famous research centers in Cambridge and Paris. In March 1944, he sent a detailed plan to the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust. He argued that India needed a strong research school in fundamental physics. This would help not only advanced physics but also practical uses in industry. He also believed that if India developed nuclear energy, it would need its own experts.

The Tata Trust agreed to fund the new institute in April 1944. In June 1945, the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) was founded. It first operated in the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. By October, it moved to Bombay. TIFR even started in the bungalow where Bhabha was born. Later, it moved to the old Royal Yacht Club buildings.

Bombay was chosen because the local government also wanted to support the institute. TIFR grew quickly under Bhabha's leadership. By 1954, Bhabha focused more on managing TIFR than on publishing scientific papers.

Some of TIFR's research groups, like those in nuclear chemistry, later moved to Trombay. This helped create a plan to use nuclear energy for power. TIFR also had a unit that made electronics. It also had a group that studied cosmic rays, which discovered new particles.

Bhabha remained the Director of TIFR until his death in 1966.

India's Nuclear Energy Program

Atomic Energy Commission

On April 26, 1948, Bhabha wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. He suggested that a small, powerful group should manage the development of atomic energy. This group would report directly to the Prime Minister. This led to the creation of the Atomic Energy Commission of India (AEC) on August 10, 1948. Nehru appointed Bhabha as its first chairman.

The work of the AEC was kept secret. This was to protect India's research and allow cooperation with other countries. Bhabha and Nehru had a close relationship. Nehru often found time to talk with Bhabha about important matters.

Bhabha realized that the atomic energy program needed its own special lab. So, he suggested building a new facility. In 1954, the Atomic Energy Establishment Trombay (AEET) began operating. In the same year, Bhabha became the secretary of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE). This department was directly under the Prime Minister.

Before 1954, the AEC mainly focused on finding radioactive minerals and doing limited research. But with the DAE, Bhabha had more freedom to set priorities. Nuclear policy was not often discussed in public or in Parliament during this time.

Three-Stage Plan for Nuclear Power

Bhabha is famous for creating a special plan for India's nuclear power. India has a lot of thorium but not much uranium. So, Bhabha's plan focused on using thorium to produce energy. He presented this plan in 1954. This strategy was different from other countries. It became India's official three-stage nuclear power program in 1958.

Bhabha explained the plan like this:

- First stage: Use natural uranium to start power stations. These stations would produce plutonium.

- Second stage: Use the plutonium from the first stage. These power stations would make electricity and turn thorium into a special type of uranium called U-233.

- Third stage: Build advanced power stations that use U-233. These would produce even more fuel than they use.

In 1952, a government company called Indian Rare Earths was set up. Its job was to get rare elements and thorium from sands in Kerala. Bhabha was a director of this company.

In August 1956, India's first nuclear reactor, APSARA, started working. It was a small research reactor. This made India the first Asian country (besides the Soviet Union) to have a nuclear reactor. APSARA helped Indian scientists do experiments and produce plutonium.

Later, India and Canada agreed to build a larger reactor called CIRUS. This reactor started in 1960. It was the most powerful reactor in Asia at the time. CIRUS also became India's first source of plutonium. Some of this plutonium was later used in India's 1974 peaceful nuclear explosion.

To support CIRUS, a plant was built in Nangal to produce "heavy water." This plant started in 1962.

In 1958, Bhabha decided to build a plant in Trombay to reprocess plutonium. This plant, called Phoenix, was finished in 1964. It worked with CIRUS to produce India's first plutonium that could be used for special purposes.

Even with these facilities, India wasn't producing nuclear energy yet. So, in 1962, General Electric was hired to build two nuclear reactors in Tarapur. These reactors, the Tarapur Atomic Power Stations (TAPS), used enriched uranium. Bhabha was able to get very good terms for India in this deal. He also made sure that international safety checks would only apply to the TAPS facility itself.

International Atomic Energy Agency

In the 1950s, Bhabha represented India at meetings of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). He was also the President of a United Nations conference on the peaceful uses of atomic energy in Geneva in 1955.

Bhabha strongly argued against the IAEA having too much control over nuclear materials. He believed that countries had the right to produce and keep nuclear materials for peaceful power programs. Thanks to his efforts, the IAEA's final rules focused on ensuring materials weren't used for military purposes. Glenn T. Seaborg, a US Atomic Energy Commission chairman, praised Bhabha's strong negotiating skills.

Debate on Nuclear Explosives

Bhabha knew that international rules might not stop a country from developing nuclear weapons. In 1959, he told a government committee that India's nuclear research was advanced enough to build nuclear weapons without outside help. In 1960, he estimated it would take India "about a year" to build a nuclear bomb.

A US report in 1964 noted that while India probably hadn't decided to build weapons, everything they had done so far would allow them to start a weapons program if they wanted to.

After China tested a nuclear bomb in 1964, Bhabha began to publicly suggest that India should also build nuclear explosives. However, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri was against building nuclear weapons. He wanted India to focus on peaceful uses of atomic energy.

Bhabha stated that a nuclear explosion would be much cheaper than using traditional explosives like TNT. This cost estimate was debated, but Bhabha's arguments influenced the public. Some political groups in India also pushed for building a nuclear bomb.

In a cabinet meeting, Bhabha's idea for a nuclear weapon program gained support from some ministers. However, Prime Minister Shastri, who believed in non-violence, was against it. He argued that a nuclear bomb would be very expensive and lead to an arms race. Shastri successfully convinced Parliament to delay a decision on nuclear weapons.

Instead, Parliament decided to speed up the development of nuclear technology. This would allow India to build nuclear weapons later if needed. Shastri also announced that India would develop "peaceful nuclear explosives." These devices, while intended for things like digging tunnels, are technically similar to nuclear weapons. This decision was seen as a compromise to gain Bhabha's support.

Historians believe this marked the start of India's policy of keeping a "nuclear option." This meant India would have the ability to build nuclear weapons if needed, but wouldn't commit to it right away.

After the 1965 war with Pakistan, pressure to build nuclear weapons grew. However, Bhabha stated that the main limit was not policy, but the need for more advanced technology.

Bhabha also secretly met with US officials to explore importing nuclear explosive technology. But this option closed with the creation of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. After Bhabha's death, Indian scientists continued working on nuclear devices. This led to the 1974 Pokhran test.

Interest in and Support of the Arts

Homi Bhabha loved classical music and opera. He even pushed for Vienna to be the headquarters of the IAEA so he could attend operas there. His brother, Jamshed Bhabha, said that for Homi, the arts were as important as science. He believed art was "what made life worth living."

Bhabha was a talented painter. He decorated his home with his own abstract paintings. He was also a key supporter of the Bombay Progressive Artists' Group. This group of artists aimed to show India's new identity after gaining independence. Bhabha collected early works from these artists for the TIFR. Today, TIFR still has a large collection of modern Indian art, which is open to the public.

Awards and Honors

Bhabha's doctoral work earned him the Adams Prize in 1942, making him the first Indian to receive it. He also received a Hopkins Prize in 1948.

He became well-known internationally for his work on how positrons scatter off electrons, which is now called Bhabha scattering. His other important contributions included work on Compton scattering and advancing nuclear physics. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Physics several times between 1951 and 1956.

In 1954, he received the Padma Bhushan, India's third-highest civilian award. He was also elected an honorary fellow of his college in Cambridge and of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 1958, he became a Foreign Honorary Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He also led the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics from 1960 to 1963. Bhabha received many honorary degrees from universities around the world.

Death

Homi Bhabha died on January 24, 1966, when Air India Flight 101 crashed near Mont Blanc in the Alps. The official reason for the crash was a misunderstanding between the pilot and Geneva Airport about the plane's position.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi expressed deep sadness at his death. She said it was a "terrible blow" for India's atomic energy program. She remembered his wide-ranging mind and his dedication to strengthening India's science.

Claims about his Death

There have been some theories about the plane crash. Some people have claimed that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was involved. They suggest this was done to stop India's nuclear program.

A journalist named Gregory Douglas claimed that a former CIA agent told him the CIA was responsible for Bhabha's death. This agent supposedly said a bomb exploded on the plane. However, these are just claims and theories, and there is no official proof.

Legacy

Homi Bhabha is remembered as the "father of the Indian nuclear program" and one of India's most important scientists. After his death, the Atomic Energy Establishment in Mumbai was renamed the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre in his honor.

Bhabha encouraged research in many fields, including electronics, space science, and radio astronomy. The Ooty Radio Telescope in India, one of the world's largest telescopes, was built because of his efforts. Many research institutes, like the Tata Memorial Hospital and the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, received early funding from the Department of Atomic Energy under Bhabha. He also helped Vikram Sarabhai set up the Indian National Committee for Space Research, which led to India's space program.

Several institutions are named after him, such as the Homi Bhabha National Institute and the Homi Bhabha Centre for Science Education.

Bhabha's family home, Mehrangir, was inherited by his brother Jamshed Bhabha. Jamshed, who also supported the arts, left the bungalow to the National Centre for the Performing Arts. The bungalow was later sold and demolished, despite efforts to preserve it as a memorial to Homi Bhabha.

See also

- India's three-stage nuclear power programme

- Abdul Qadeer Khan

- Bertrand Goldschmidt

- Deng Jiaxian

- Igor Kurchatov

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Leo Szilard

- John von Neumann

- William Penney, Baron Penney

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |