Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

|

|

|---|---|

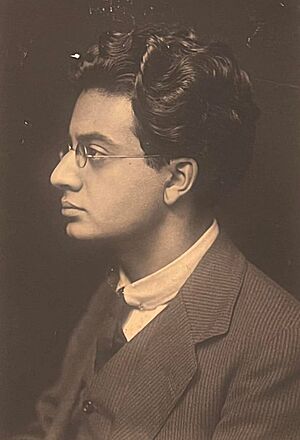

Sorabji in 1917

|

|

| Born |

Leon Dudley Sorabji

14 August 1892 Chingford, Essex, England

|

| Died | 15 October 1988 (aged 96) Winfrith Newburgh, Dorset, England

|

| Occupation |

|

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (born Leon Dudley Sorabji; 14 August 1892 – 15 October 1988) was an English composer, music critic, pianist, and writer. His music, created over seventy years, includes short pieces and works lasting many hours. He was one of the most productive 20th-century composers.

Sorabji is best known for his piano music. This includes nocturnes like Gulistān and Villa Tasca. He also wrote large, complex pieces. These include seven symphonies for piano solo, four toccatas, Sequentia cyclica, and 100 Transcendental Studies. He felt different from English society because of his mixed family background. He preferred to live a quiet, private life.

Sorabji was taught at home. His mother was English, and his father was a Parsi businessman from India. His father set up a trust fund that meant the family did not need to work. Sorabji did not like performing much and was not a virtuoso (a highly skilled performer). Still, he played some of his music in public between 1920 and 1936.

In the late 1930s, he changed his mind about public performances. He placed rules on playing his works, which he removed in 1976. His music was not heard much during these years. He stayed known mainly through his writings, like the books Around Music and Mi contra fa. During this time, he left London and moved to Corfe Castle, Dorset. We know little about Sorabji's later life. Most information comes from letters he wrote to friends.

Sorabji mostly taught himself how to compose. At first, he liked modern music. But later, he did not like much of the music of his time. He was inspired by composers like Ferruccio Busoni, Claude Debussy, and Karol Szymanowski. He created a style that mixed Baroque forms with many polyrhythms. His music also blended tonal and atonal sounds and had rich ornamentation.

He mainly wrote for the piano, like other composer-pianists he admired, such as Franz Liszt and Charles-Valentin Alkan. But he also wrote for orchestra, chamber groups, and organ. His harmonies and complex rhythms were ahead of their time. They were similar to music from the mid-20th century onwards. His music was mostly not published until the early 2000s. However, interest in his works has grown since then.

Contents

A Composer's Life

Early Years

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji was born in Chingford, Essex (now Greater London), on 14 August 1892. His father, Shapurji Sorabji (1863–1932), was a Parsi engineer from Bombay, India. He was a businessman and industrialist, like many of his family members. Sorabji's mother, Madeline Matilda Worthy (1866–1959), was English. She was born in Camberwell, Surrey (now South London). People said she was a singer, pianist, and organist, but there is not much proof. They married on 18 February 1892, and Sorabji was their only child.

We do not know much about Sorabji's early life and how he started in music. He reportedly began learning piano from his mother at age eight. Later, Emily Edroff-Smith, a musician and piano teacher who was a friend of his mother, helped him. Sorabji went to a school with about twenty boys. There, he studied piano, organ, harmony, German, and Italian. His mother also taught him and took him to concerts.

Starting in Music (1913–1936)

We learn a lot about Sorabji's life from his letters to composer and critic Peter Warlock. Their letters started in 1913. Warlock encouraged Sorabji to become a music critic and focus on composing. Sorabji had passed his matriculation exams. He decided to study music privately because Warlock's views on universities made him change his plans.

So, from the early 1910s until 1916, Sorabji studied music with pianist and composer Charles A. Trew. Around this time, he became friends with composers Bernard van Dieren and Cecil Gray. These two were also friends with Warlock. We do not know why Sorabji was not called to serve during World War I. He later praised conscientious objectors for their bravery. However, there is no proof he tried to become one.

Sorabji's letters from this time show his early feelings of being an outsider. He felt different because of his mixed background. He also developed a non-English identity. Sorabji joined the Parsi community in 1913 or 1914. He attended a Navjote ceremony and changed his name. He had reportedly been treated badly by other boys at school. His tutor, who wanted to make him an English gentleman, would say bad things about India. The tutor would also hit him on the head with a large book, causing headaches. These experiences are thought to be why he disliked England. He soon described English people as treating foreigners badly on purpose.

In late 1919, Warlock sent music critic Ernest Newman some of Sorabji's scores. These included his First Piano Sonata. Newman ignored them. In November that year, Sorabji met composer Ferruccio Busoni privately and played the piece for him. Busoni had some doubts about the work. But he gave Sorabji a letter of recommendation, which helped get it published. Warlock and Sorabji then publicly accused Newman of ignoring and sabotaging Sorabji's work. This led Newman to explain why he could not meet Sorabji or review his scores. Warlock called Newman's behavior stubborn. The issue was settled after the journal Musical Opinion published letters between Sorabji and Newman.

Sorabji has been called a late starter because he did not compose music before age 22. Even before he started composing, he was interested in new ideas in art music. This was at a time when such music was not popular in England. This interest, along with his background, made him seem like an outsider. The modern style, longer lengths, and technical difficulty of his works confused critics and audiences.

While some disliked his music, other musicians liked it. After hearing Sorabji's Le jardin parfumé—Poem for Piano Solo in 1930, English composer Frederick Delius sent him a letter. Delius admired the piece's "real sensuous beauty." Around the 1920s, French pianist Alfred Cortot and Austrian composer Alban Berg also became interested in his work.

Sorabji first played his music in public in 1920. He gave occasional performances in Europe over the next ten years. In the mid-1920s, he became friends with composer Erik Chisholm. This led to the most active period of his piano career. Their letters began in 1926, and they first met in April 1930 in Glasgow, Scotland. Later that year, Sorabji joined Chisholm's new Active Society for the Propagation of Contemporary Music. This group's concerts featured many famous composers and musicians. Sorabji said he was "a composer—who incidentally, merely, plays the piano." Yet, he was the guest performer who appeared most often in the series. He came to Glasgow four times. He played some of his longest works there. He premiered Opus clavicembalisticum and his Fourth Sonata in 1930. He premiered his Toccata seconda in 1936. He also performed Nocturne, "Jāmī" in 1931.

Years of Quiet Life

Changes in Life and Music (1936–1949)

On 10 March 1936, in London, pianist John Tobin played part of Opus clavicembalisticum. The performance lasted 90 minutes, twice as long as it should have. Sorabji left before it ended. He said he had not attended, paid for, or supported the performance. Many leading critics and composers were at the concert. They wrote negative reviews in the newspapers, which badly hurt Sorabji's reputation.

Sorabji gave the first performance of his Toccata seconda in December 1936. This was his last public appearance. Three months earlier, he had said he was no longer interested in his works being performed. Over the next ten years, he often spoke against his music being widely shared.

Sorabji eventually placed rules on performances of his works. People called this a "ban," but it was not an official rule. Instead, he just discouraged others from playing his music in public. This was not new; even his first published scores had a note saying he reserved the right to perform them. Few concerts with his music took place in those years. Most were private or given by friends with his permission. He turned down offers to play his works in public.

His withdrawal from the music world is often linked to Tobin's concert. But other reasons have been suggested. These include the deaths of people he admired (like Busoni). Also, the growing popularity of Igor Stravinsky and twelve-tone composition might have played a part. Still, the 1930s were a very creative time for Sorabji. He wrote many of his largest works. His work as a music critic also reached its peak. In 1938, Oxford University Press became the publisher for his works. They continued until his death in 1988.

A big reason for Sorabji's change was his money situation. Sorabji's father had returned to Bombay after his marriage in 1892. He was important in India's engineering and cotton industries. He loved music and paid for 14 of Sorabji's compositions to be published between 1921 and 1931. However, there is little proof he lived with the family, and he did not want his son to be a musician. In October 1914, Sorabji's father set up the Shapurji Sorabji Trust. This fund would give his family money for life, so they would not need to work.

Sorabji's father was affected by the fall of the pound and rupee in 1931. He stopped paying for Sorabji's scores to be published that same year. He died in Bad Nauheim, Germany, on 7 July 1932. Sorabji's second trip to India (May 1933 to January 1934) showed that his father had been living with another woman since 1905. He had married her in 1929. Sorabji and his mother were not included in his will. They received much less money than his Indian family. A legal case started around 1936. The marriage was declared invalid by a court in 1949. But the money could not be recovered.

Sorabji dealt with this uncertainty by starting yoga. He said it helped him find inspiration and focus. He also said it helped him gain self-discipline. He wrote that his life, once "chaotic, without form or shape," now had "an ordered pattern and design." This practice inspired him to write an essay called "Yoga and the Composer." It also led him to compose the Tāntrik Symphony for Piano Alone (1938–39). This work has seven movements named after body centers in tantric and shaktic yoga.

Sorabji did not serve in the military or do civic duties during World War II. This is thought to be because he was very independent. His public letters and music criticism continued. He never wrote about the war in his works. Many of Sorabji's 100 Transcendental Studies (1940–44) were written during German bombings. He composed at night and early morning in his home in Clarence Gate Gardens (Marylebone, London). This was even when most other buildings were empty. War records show that a high explosive bomb hit Siddons Lane, near the back entrance to his old home.

Admirers and Quiet Life (1950–1968)

In 1950, Sorabji left London. In 1956, he moved into The Eye, a house he built for himself in Corfe Castle, Dorset. He had been on holidays in Corfe Castle since 1928 and loved the place. In 1946, he wanted to live there permanently. Once he settled in the village, he rarely left. Sorabji felt disliked by the English music world. He especially disliked London, calling it the "International Human Rubbish dump." Living costs also played a part in his decision to leave the city. As a critic, he earned no money. While he lived simply, he sometimes had money problems.

Sorabji was very close to his mother. This was partly because his father left them, which affected their money. She traveled with him, and he spent almost two-thirds of his life with her until the 1950s. He also took care of his mother in her last years when they were not living together.

Even though he lived a quiet life, Sorabji had a group of close admirers. People worried about the future of his music. Sorabji had not recorded any of his works, and none had been published since 1931. Frank Holliday, an English trainer and teacher, made the biggest effort to save his music. Holliday met Sorabji in 1937 and was his closest friend for about forty years. From 1951 to 1953, Holliday arranged for a letter to be sent to Sorabji. It invited him to record his own music. Sorabji received the letter, signed by 23 admirers, soon after. But he did not make recordings then, even with a check for 121 guineas included.

Sorabji was worried about how copyright laws would affect his music. But Holliday finally convinced him after years of trying. A little over 11 hours of music were recorded at Sorabji's home between 1962 and 1968. The tapes were not meant for public use. However, some recordings were leaked. Parts were included in a 55-minute WBAI broadcast in 1969. A three-hour program by WNCN in 1970 was also broadcast. The latter was played several times in the 1970s. This helped spread and understand Sorabji's music.

Sorabji and Holliday's friendship ended in 1979. This was due to disagreements about Sorabji's musical legacy. Unlike Sorabji, who destroyed many of their letters, Holliday kept his collection. This collection of Sorabji's letters and other items is a very important source of information about the composer. Holliday took many notes during his visits to Sorabji. He often believed everything Sorabji told him. McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) bought the collection in 1988.

Another devoted admirer was Norman Pierre Gentieu. He was an American writer who found Sorabji after reading his book Around Music (1932). Gentieu sent Sorabji supplies because of shortages in England after the war. He continued to do so for the next forty years. In the early 1950s, Gentieu offered to pay to microfilm Sorabji's main piano works. He also offered to provide copies to certain libraries. In 1952, Gentieu set up a fake group (the Society of Connoisseurs). This was to hide that he was paying for it. But Sorabji suspected it was a trick. Microfilming (which included all of Sorabji's unpublished music) began in January 1953. It continued until 1967 as new works were created. Copies of the microfilms became available in several libraries and universities in the United States and South Africa.

Over the years, Sorabji grew tired of composing. Health problems, stress, and tiredness got in the way. He started to dislike writing music. After finishing the Messa grande sinfonica (1955–61), which is 1,001 pages long, Sorabji wrote that he did not want to compose anymore. In August 1962, he suggested he might stop composing and destroy his existing music. Extreme worry and exhaustion from personal, family, and other issues, including the private recordings, had worn him out. He took a break from composing. He eventually returned to it but worked more slowly. He mostly wrote short pieces. In 1968, he stopped composing and said he would not write any more music. We do not have records of how he spent the next few years. His public letters also became fewer.

New Public Attention (1969–1979)

In November 1969, composer Alistair Hinton, then a student, found Sorabji's music in a library. He wrote a letter to Sorabji in March 1972. They met for the first time at Sorabji's home on 21 August 1972. They quickly became good friends. Sorabji started asking Hinton for advice on legal and other matters. In 1978, Hinton and music expert Paul Rapoport microfilmed Sorabji's music that had not been copied yet. In 1979, Sorabji wrote a new will. He left all his music to Hinton, who became his literary and musical executor.

Sorabji had not written any music since 1968. But he started composing again in 1973 because Hinton was so interested in his work. Hinton also convinced Sorabji to let Yonty Solomon play his works in public. This permission was given on 24 March 1976. It marked the end of the "ban." However, another pianist, Michael Habermann, might have received early approval even before that. Concerts with Sorabji's music became more common. This led him to join the Performing Right Society and earn a small income from royalties.

In 1977, a TV show about Sorabji was made and broadcast. The show mostly showed still photos of his house. Sorabji did not want to be seen. There was only one short shot of him waving to the camera crew as they left. In 1979, he appeared on BBC Scotland for the 100th birthday of Francis George Scott. He also appeared on BBC Radio 3 to remember Nikolai Medtner's 100th year. The BBC Scotland broadcast led to Sorabji's first meeting with Ronald Stevenson. He had known and admired Stevenson for over 20 years. Soon after, Sorabji received a request from Gentieu. He wrote Il tessuto d'arabeschi (1979) for flute and string quartet. He dedicated it "To the memory of Delius" and was paid £1,000.

Last Years

Sorabji finished his last piece, Due sutras sul nome dell'amico Alexis, in 1984. He stopped composing after that because his eyesight was failing. He also found it hard to write by hand. His health got much worse in 1986. This forced him to leave his home and spend months in a Wareham hospital. In October of that year, he put Hinton (his only heir) in charge of his personal matters. By this time, the Shapurji Sorabji Trust had run out of money. His house and belongings (including about 3,000 books) were put up for auction in November 1986.

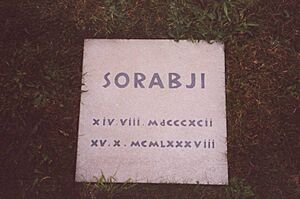

In March 1987, he moved into Marley House Nursing Home. This was a private nursing home in Winfrith Newburgh (near Dorchester, Dorset). He was always in a chair there and received daily nursing care. In June 1988, he had a mild stroke. This left him slightly mentally affected. He died of heart failure and arteriosclerotic heart disease on 15 October 1988, at age 96. He was cremated in Bournemouth Crematorium on 24 October. The funeral service took place in Corfe Castle at the Church of St. Edward, King and Martyr, on the same day. His remains are buried in "God's Acre," the Corfe Castle cemetery.

Personal Life

Myths and Reputation

During Sorabji's life and after his death, many stories about him spread. To correct these, experts have studied his way of composing, his performing skills, and the size and complexity of his pieces. This has been hard because few documents about his life have survived. His letters to friends are the main source of information. However, many of these letters are missing. Sorabji often threw away large amounts of his letters without looking at them. Marc-André Roberge, who wrote Sorabji's first biography, says that "there are years for which hardly anything can be reported."

Sorabji himself spread some of these stories. He claimed to have relatives high up in the Catholic Church. He wore a ring that he said belonged to a dead Sicilian cardinal. He also said the ring would go to the Pope after his death. Villagers in Corfe Castle sometimes called him "Sir Abji" and "Indian Prince." Sorabji often gave wrong information about himself to people who wrote dictionaries. One of them, Nicolas Slonimsky, wrongly wrote in 1978 that Sorabji owned a castle. Slonimsky once called him "the most enigmatic composer now living."

For a long time, people thought Sorabji's mother was Spanish-Sicilian. But the Sorabji expert Sean Vaughn Owen showed she was born to English parents. They were baptized in an Anglican church. Owen found that she often told false stories. He suggested this influenced Sorabji, who also made a habit of misleading others. Owen concludes that even though Sorabji seemed like an unfriendly and superior person, his friends found him serious but also kind and welcoming. He sums up the differences in Sorabji's reputation and behavior:

The contradictions between his reputation and the actuality of his existence were known to Sorabji and they appear to have given him much amusement. This sense of humour was detected by many in the village, yet they too were prone to believe his stories. The papal connection ... was a particular favourite and as much as Sorabji detested being spotlighted in a large group, he was perfectly content in more intimate situations bringing direct attention to his ring or his thorny attitude regarding the ban on his music.

Social Life

Many of Sorabji's friends were not musicians. He said their human qualities meant more to him than their musical knowledge. He looked for kindness in others and said he depended emotionally on his friends' affection. He could be very loyal to them, though he admitted he preferred being alone. Some of his friendships, like with Norman Peterkin or Hinton, lasted until one of them died. Others ended. Though Sorabji had often spoken harshly about the English, in the 1950s, he admitted he had not been fair. He recognized that many of his close friends were English.

Best, Sorabji's companion, suffered from depression and several health problems from birth. Around 1970, he started having electroconvulsive therapy. This caused him a lot of worry. Sorabji was upset by this. Owen believes that the treatment and Best's mental health issues made them both want to be alone even more. Sorabji valued his privacy greatly. He even called himself a "claustrophiliac" (someone who loves enclosed spaces). He has often been called a misanthrope (someone who dislikes people). He planted over 250 trees around his house. His house also had many signs to keep unwanted visitors away. Sorabji did not like having two or more friends visit at the same time. He would only accept one friend at a time, about once or twice a year. In a text he never published, he explained why he lived alone. He said, "my own failings are so great that they are as much as I can put up with in comfort—those of other people superadded I find a burden quite intolerable."

Religious Views

Sorabji was interested in the occult, numerology, and similar topics. Rapoport suggested that Sorabji hid his birth year because he feared it could be used against him. Early in his life, Sorabji published articles on the paranormal. He also included occult symbols and references in his works. In 1922, he met the occultist Aleister Crowley. He soon dismissed Crowley as a "fraud" and "the dullest of dull dogs." He also had a 20-year friendship with Bernard Bromage, an English writer on mysticism. Bromage was a co-trustee of the Shapurji Sorabji Trust between 1933 and 1941. He created a flawed index for Sorabji's book Around Music, which displeased the composer. He also seemed to act improperly as a trustee, causing Sorabji significant money losses. This led to his removal from the Trust and the end of their friendship around 1942. Occult themes rarely appeared in Sorabji's music and writings after that.

Sorabji spoke well of the Parsis. However, his experiences with them in India in the 1930s upset him. He adopted only a few parts of Zoroastrianism. He then cut ties with various Parsi and Zoroastrian groups because he disagreed with their actions. However, he kept an interest in his Persian heritage. He insisted that his body should be cremated after his death. This is an alternative to using the Tower of Silence.

Sorabji's feelings about Christianity were mixed. Early in his life, he criticized it for causing war. He called it a hypocritical religion. However, he later admired the Catholic Church. He said the most valuable parts of European civilization came from it. His interest in the Catholic Mass inspired his largest work, the Messa grande sinfonica. Although he said he was not Catholic, he might have privately accepted some parts of the faith.

Music

Early Works

People have wondered about earlier works. But Sorabji's first known (though lost) piece is a 1914 piano transcription. It was of Delius's orchestral piece In a Summer Garden. His early works were mostly piano sonatas, songs, and piano concertos. Among these, Piano Sonatas Nos. 1–3 (1919; 1920; 1922) are the most important. They are known for being in one movement and not having clear themes. The main criticism against them is that they lack a consistent style. Sorabji himself did not like his early works much. He called them unoriginal and messy. He even thought about destroying many of their manuscripts later in his life.

Middle-Period Works and Symphonic Style

The Three Pastiches for Piano (1922) and Le jardin parfumé (1923) are often seen as the start of Sorabji's mature composing. Sorabji himself thought his Organ Symphony No. 1 (1924) was the beginning. This was his first work to use many forms like the chorale prelude, the passacaglia, and the fugue. These forms come from baroque music. When he combined these with his earlier ideas, his "symphonic style" appeared. This style is seen in most of his seven symphonies for piano solo and three symphonies for organ. The first piece to use this style's structure was his Fourth Piano Sonata (1928–29). It has three parts:

- An opening movement with many themes;

- A slow movement with ornaments (called a nocturne);

- A finale with many sections, including a fugue.

Sorabji's symphonic first movements are similar in structure to his Second and Third Piano Sonatas. They are also like the last movement of his First Organ Symphony. They seem to be based on the fugue or the sonata-allegro form. But they are different from how those forms are usually used. The introduction and development of themes are not guided by normal tonal rules. Instead, they are guided by how the themes, as music expert Simon John Abrahams says, "battle with each other for domination of the texture." These movements can last over 90 minutes. Their themes vary greatly. The opening movement of his Fourth Piano Sonata has seven themes. His Second Piano Symphony's opening has sixty-nine. There is still a "main theme" or "motto" in these multi-theme movements. It is given the most importance and appears throughout the rest of the piece.

The nocturnes are usually thought to be among Sorabji's easiest works to listen to. They are also some of his most highly praised. Pianist Michael Habermann called them "the most successful and beautiful of [his] compositions." Pianist Fredrik Ullén said they are "perhaps... his most personal and original contribution as a composer." Sorabji's descriptions of his Symphony No. 2, Jāmī, help us understand how they are organized. He compared the piece to his nocturne Gulistān. He wrote about the symphony's "self-cohesive texture relying upon its own inner consistency and cohesiveness without relation to thematic or other matters."

Melodies are used freely in such works. Instead of themes, ornamentation and textural patterns become most important. The nocturnes explore free, impressionistic harmonies. They are usually played at quiet dynamic levels. However, some later ones have loud, fast parts. They can be stand-alone works, like Villa Tasca. Or they can be parts of larger pieces, like "Anāhata Cakra." This is the fourth movement of his Tāntrik Symphony for Piano Alone. Sections called "aria" and "punta d'organo" are included in this style. The "punta d'organo" parts have been compared to "Le gibet" from Maurice Ravel's Gaspard de la nuit.

Sorabji's fugues usually follow traditional ways of developing music. They are the most atonal and least polyrhythmic of his works. After an introduction presents a subject and one to four countersubjects, the themes are developed. This is followed by a stretto (a section where themes overlap). This leads to a part with longer note values and thicker lines that form chords. If a fugue has many themes, this pattern repeats for each subject. Material from all introductions is combined near the end. Sorabji's fugue writing has sometimes been viewed with doubt or criticized. The subjects can lack the frequent changes of direction found in most melodies. Some of the fugues are among the longest ever written. One is the two-hour "Fuga triplex," which ends the Second Symphony for Organ.

This structure was used and improved in most of Sorabji's piano and organ symphonies. Sometimes, a set of variations replaces the slow movement. Starting with the Second Symphony for Piano (1954), fugues are placed either in the middle of the work or just before a closing slow movement. Interludes and moto perpetuo-type sections connect larger movements. They also appear in Sorabji's later fugues. For example, in the Sixth Symphony for Piano (1975–76), the "Quasi fuga" alternates between fugal and non-fugal sections.

Other important forms in Sorabji's music are the toccata and the stand-alone variation set. The variation sets, along with his non-orchestral symphonies, are his most ambitious works. They have been praised for their imagination. Sequentia cyclica super "Dies irae" ex Missa pro defunctis (1948–49) is a set of 27 variations on the original Dies irae plainchant. Some consider it his greatest work. His four multi-movement toccatas are generally smaller. They use the structure of Busoni's work of the same name as their starting point.

Late Works

In 1953, Sorabji said he was not interested in composing anymore. He described Sequentia cyclica (1948–49) as "the climax and crown of his work for the piano." He also said it was "in all probability, the last he will write." His speed of composing slowed down in the early 1960s. Later that decade, Sorabji promised to stop composing, which he did in 1968.

Hinton played a key role in Sorabji's return to composing. Sorabji's next two pieces, Benedizione di San Francesco d'Assisi and Symphonia brevis for Piano, were written in 1973. This was the year after he and Hinton first met. These works marked the start of his "late style." This style is known for thinner textures and more use of extended harmonies. Roberge writes that Sorabji, after finishing the first movement of Symphonia brevis, "felt that it broke new ground for him." He thought it was his most mature work, where he was doing new things. Sorabji said his late works were designed "as a seamless coat." This meant that parts could not be separated without ruining the music's flow. During his late period, and before his break from composing, he also created "aphoristic fragments." These were short musical ideas that could last only a few seconds.

Inspiration and Influences

Sorabji's early influences included Cyril Scott, Ravel, Leo Ornstein, and especially Alexander Scriabin. He later became more critical of Scriabin. After meeting Busoni in 1919, Busoni greatly influenced his music and writings. His later work was also much influenced by the skilled writing of Charles-Valentin Alkan and Leopold Godowsky. He also learned from Max Reger's use of counterpoint. The impressionist harmonies of Claude Debussy and Karol Szymanowski also inspired him. Hints of various composers appear in Sorabji's works. These include his Sixth Symphony for Piano and Sequentia cyclica. They contain sections called "Quasi Alkan" and "Quasi Debussy."

Eastern culture partly influenced Sorabji. According to Habermann, this shows in his music in several ways. These include very flexible and uneven rhythms, lots of ornamentation, a feeling of being improvised and timeless, frequent polyrhythmic writing, and the huge size of some of his pieces. Sorabji wrote in 1960 that he almost never tried to mix Eastern and Western music. Although he spoke positively about Indian music in the 1920s, he later criticized what he saw as its limits. This included a lack of theme development in the raga, which focused more on repetition. A major source of inspiration was his reading of Persian literature. This was especially true for his nocturnes. Sorabji and others described these as bringing to mind tropical heat or a rainforest.

Various religious and occult references appear in Sorabji's music. These include hints of the tarot, a setting of a Catholic blessing, and sections named after the seven deadly sins. Sorabji rarely meant for his works to tell a story or be programmatic. Pieces like "Quaere reliqua hujus materiei inter secretiora" and St. Bertrand de Comminges: "He was laughing in the tower" (both inspired by ghost stories by M. R. James) have been called programmatic. However, he often criticized attempts to represent stories or ideas in music.

Sorabji's interest in numerology can be seen in how he used numbers. He would assign a number to the length of his scores. He also used numbers for the amount of variations in a piece or the number of bars in a work. Recent studies on Sorabji's music suggest he was interested in the golden section for dividing forms. Squares, repdigits, and other numbers with special meaning are common. Page numbers might be used twice or left out to get the desired result. For example, the last page of Sorabji's Piano Sonata No. 5 is numbered 343a, even though the score has 336 pages. This kind of change is also seen in his numbering of variations.

Sorabji claimed to be of Spanish-Sicilian ancestry. He composed pieces that show his love for Southern European cultures. Examples include Fantasia ispanica, Rosario d'arabeschi, and Passeggiata veneziana. These works have a Mediterranean feel. They are inspired by Busoni's Elegy No. 2, "All'Italia! in modo napolitano". They are also inspired by the Spanish music of Isaac Albéniz, Debussy, Enrique Granados, and Franz Liszt. These are considered among his more showy and less musically ambitious works. French culture and art also appealed to Sorabji. He set French texts to music. About 60 percent of his known works have titles in Latin, Italian, and other foreign languages.

Harmony, Counterpoint, and Form

Sorabji's counterpoint style comes from Busoni and Reger. So did his use of theme-based baroque forms. His use of these often contrasts with the more free, improvised writing of his fantasias and nocturnes. Because these pieces do not have clear themes, they have been called "static." Abrahams describes Sorabji's approach as built on "self-organizing" (baroque) and non-thematic forms. These forms can be expanded as needed. Their flow is not controlled by themes. While Sorabji wrote pieces of normal or even tiny sizes, his largest works are what he is best known for. They require skills and endurance beyond what most performers have. Examples include his Piano Sonata No. 5 (Opus archimagicum), Sequentia cyclica, and the Symphonic Variations for Piano. These last about six, eight, and nine hours respectively. Roberge estimates that Sorabji's existing musical output may take up to 160 hours to perform. He describes it as "perhaps the most extensive of any twentieth-century composer."

Sorabji's harmonic language often mixes tonal and atonal elements. It frequently uses triadic harmonies and bitonal (two keys at once) combinations. It does not avoid tonal sounds. It also shows his liking for tritone and semitone relationships. Even with harsh-sounding harmonies, his music rarely has the tension found in very dissonant music. Sorabji achieved this partly by using widely spaced chords based on triadic harmonies. He also used pedal points (held notes) in the low registers. These act as sound cushions and soften harsh sounds in the upper voices. In bitonal parts, melodies might sound good within one harmonic area. But they might not sound good with melodies from the other area. Sorabji uses non-functional harmony. This means no key or bitonal relationship is allowed to become fixed. This makes his harmonies flexible. It also helps explain why he could layer semitonally opposing harmonies.

Creative Process and Notation

Because Sorabji was very private, little is known about how he composed. Early stories by Warlock said he composed without planning and did not change his work. This claim is generally doubted. It goes against what Sorabji himself said and what some of his music manuscripts show. In the 1950s, Sorabji stated that he would plan the general idea of a work long before the themes. A few sketches survive. Crossed-out parts are mostly found in his early works. Some have claimed that Sorabji used yoga to get "creative energies." But in fact, it helped him control his thoughts and gain self-discipline. He found composing tiring. He often finished works with headaches and sleepless nights afterward.

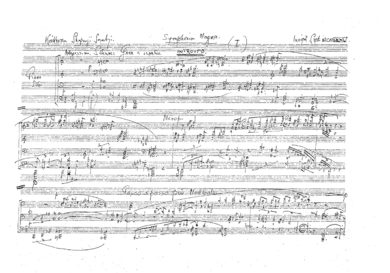

The unusual features of Sorabji's music and the "ban" led to unique things in his notation. There were few instructions on how to play the music. There was also a lack of time signatures (except in his chamber and orchestral works). He also did not always use bar lines in a systemized way. He wrote very quickly. There are many unclear parts in his original music papers. This has led to comparisons with his other traits. Hinton suggested a link between them and Sorabji's speech. He said that "[Sorabji] invariably spoke at a speed almost too great for intelligibility." Stevenson noted, "One sentence could embrace two or three languages." Sorabji's handwriting, especially after he got rheumatism, can be hard to read. After he complained about errors in one of his public letters, the editor replied, "If Mr. Sorabji will in future send his letters in typescript instead of barely decipherable handwriting, we will promise a freedom from misprints." Later in life, similar problems affected his typing.

Pianism and Keyboard Music

As a Performer

Sorabji's piano skills have been much debated. After his early lessons, he seemed to be self-taught. In the 1920s and 1930s, when he played his works in public, their supposed unplayability and his piano technique caused much argument. At the same time, his closest friends and a few others praised him as a top-class performer. Roberge says that he was "far from a polished virtuoso in the usual sense." Other writers agree with this view.

Sorabji did not like performing and struggled with the pressure of playing in public. He often said he was not a pianist. He always put composing first. From 1939, he no longer practiced the piano often. Reviews from his time noted that Sorabji tended to rush the music. He also lacked patience with quiet parts. The private recordings he made in the 1960s show big differences from his written scores. This is partly because he was impatient and not interested in playing clearly and accurately. Writers have argued that early reactions to his music were greatly affected by problems in his performances.

As a Composer

Many of Sorabji's works are for the piano or have an important piano part. His writing for the instrument was influenced by composers like Liszt and Busoni. He has been called a composer-pianist in their style. Godowsky's polyphony (many melodies at once), polyrhythms, and polydynamics (many dynamic levels at once) were especially important. This led to Sorabji regularly using the sostenuto pedal. He also used systems of three or more staves in his keyboard music. His largest such system is on page 124 of his Third Organ Symphony, with 11 staves. In some works, Sorabji wrote for the extra keys on the Imperial Bösendorfer piano. While this piano usually has extra low notes, he sometimes asked for extra notes at the high end too.

Some have praised Sorabji's piano writing for its variety. They also praised his understanding of the piano's sounds. His approach to the piano was not harsh. He stressed that his music was meant to sound like singing. He once called Opus clavicembalisticum "a colossal song." Pianist Geoffrey Douglas Madge compared Sorabji's playing to bel canto singing. Sorabji once said, "If a composer can't sing, a composer can't compose."

Some of Sorabji's piano pieces try to sound like other instruments. This is seen in notes like "quasi organo pieno" (like a full organ), "pizzicato" (plucked strings), and "quasi tuba con sordino" (like a tuba with mute). In this way, Alkan was a key inspiration. Sorabji was influenced by Alkan's Symphony for Solo Piano and the Concerto pour piano seul. He admired Alkan's "orchestral" writing for the piano.

Organ Music

Besides the piano, the organ is another important keyboard instrument in Sorabji's works. Sorabji's largest orchestral works have organ parts. But his most important contribution to organ music are his three organ symphonies (1924; 1929–32; 1949–53). All of these are large works with three main parts. They have many smaller sections and can last up to nine hours. Sorabji thought Organ Symphony No. 1 was his first mature work. He considered the Third Organ Symphony among his best achievements. He believed even the best orchestras of his time were not as good as the modern organ. He wrote about the "tonal splendour, grandeur and magnificence" of the organs in Liverpool Cathedral and the Royal Albert Hall. He described organists as being more cultured and having better musical judgment than most musicians.

Creative Transcription

For Sorabji, transcription was a creative act. It was like it was for many composer-pianists who inspired him. Sorabji agreed with Busoni's idea that composing is like transcribing an abstract idea. Performing is also a form of transcription. For Sorabji, transcription allowed older music to be changed to create a completely new work. He did this in his pastiches. He saw transcription as a way to make a piece richer and to find hidden ideas within it. His transcriptions include an adaptation of Bach's Chromatic Fantasia. In the introduction to this work, he criticized those who play Bach on the piano without "any substitution in pianistic terms." Sorabji praised performers like Egon Petri and Wanda Landowska. He liked that they took liberties in their performances. He also admired their ability to understand a composer's intentions, including his own.

Writings

As a writer, Sorabji is best known for his music criticism. He wrote for music publications in England. These included The New Age, The New English Weekly, The Musical Times, and Musical Opinion. His writings also covered topics not related to music.

Legacy

Innovation

Sorabji has been called a traditional composer. But he developed a unique style that mixed different influences. However, how people saw and reacted to his music changed over the years. His early, often modern works were mostly not understood. A 1922 review said, "compared to Mr. Sorabji, Arnold Schönberg must be a tame reactionary." Composer Louis Saguer, speaking in Darmstadt in 1949, called Sorabji a member of the musical avant-garde. He said few people would be able to understand him. Abrahams writes that Sorabji "had begun his compositional career at the forefront of compositional thought." But he "ended it seeming decidedly old-fashioned." Still, Abrahams adds that "even now Sorabji's 'old-fashioned' outlook sometimes remains somewhat cryptic."

Many similarities have been found between Sorabji and later composers. Ullén suggests that Sorabji's 100 Transcendental Studies (1940–44) might have predicted the piano music of Ligeti, Michael Finnissy, and Brian Ferneyhough. However, he warns against overstating this. Roberge compares the start of Sorabji's orchestral piece Chaleur—Poème (1916–17) to the micropolyphonic texture of Ligeti's Atmosphères (1961). Powell has noted the use of metric modulation in Sequentia cyclica (1948–49). This was composed around the same time as (and separately from) Elliott Carter's 1948 Cello Sonata. That was the first work where Carter used this technique.

Mixing chords with different root notes and using nested tuplets are common in Sorabji's works. Both have been described as predicting Messiaen's music and Stockhausen's Klavierstücke (1952–2004) by several decades. Sorabji's blending of tonality and atonality into a new way of relating harmonies has also been called an important innovation.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |