English society facts for kids

English society is all about how people in England live together, how they interact, and what their ideas and beliefs are. The history of English society shows many big changes over time, from the Anglo-Saxon period to today. These changes happened both within England and because of its relationships with other countries. Studying social history means looking at things like how many people lived in England, how people worked, the role of women and families, education, life in the countryside and cities, and how industries grew.

The distant past doesn't tell us much about how society was structured. However, big changes in how humans lived suggest that society must have changed a lot. Like much of Europe, the switch from hunting and gathering to farming around 4000 BC brought huge changes to all parts of human life. We don't know exactly what happened, but recent discoveries of permanent buildings from 3,000 years ago suggest these changes might have been slow.

One clear sign of change in prehistoric society is Stonehenge. Building huge stone circles, burial mounds, and other monuments across the British Isles likely needed people to have special jobs. Builders would have focused on monument construction to learn the skills. Since they wouldn't have time to hunt or farm, they would rely on others. This led to specialized farmers who grew food for everyone, including the builders. Many different cultures came and went in prehistoric and later times, like the Beaker people, the Celts, the Romans, and the Anglo-Saxons.

Contents

Roman Influence on Society

The Roman invasion in 54 BC probably didn't change society much at first. It was mostly just a new group of rulers. However, many new ideas slowly took hold. Ireland was not affected at all. We get our first detailed written records of Britain and its tribal society from the Romans, especially from a writer named Tacitus. We learn interesting things about society before the Romans, even if they only mentioned it briefly. For example, powerful women like Cartimandua and Boudica were very important.

Living in cities wasn't new to Britain before the Romans, but it was a lifestyle the Romans preferred. Only a few Romanized Britons got to live this way. Becoming "Romanized" was a key part of the Roman plan to take over. British rulers who happily adopted Roman ways were rewarded as "client kings." A good example is Togidubnus and his very modern Fishbourne Roman Palace. To control the country, the Romans built a huge network of roads. These roads were not just amazing engineering projects; they also became the main ways for people to communicate across the country. The Romans brought many other new things like writing and plumbing. But it's not clear how many of these were only for the rich, or if some were even lost and rediscovered later.

Early Medieval Society

When the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century, people think it caused a lot of trouble and chaos. But we don't fully understand what happened. We do know from archaeological finds that expensive goods became rare. Roman cities also started to be abandoned. However, many people in Britain had never had such things anyway. Many different groups of people took advantage of the Romans being gone. But how they affected British society is still unclear. Instead of one big Roman rule, there were many smaller, often fighting, societies. Later, these included the heptarchy, which was seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. People stopped thinking of themselves as part of a big Roman empire and went back to smaller tribal groups.

The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons is a much-debated event. Historians still question how much they killed, moved, or mixed with the people already living there. What is clear is that a separate Anglo-Saxon society was set up in the southeast of the island. This society would eventually become England and had a more Germanic feel. These new arrivals had not been conquered by the Romans. Their society was perhaps similar to Britain's. The main difference was their pagan religion. The remaining northern areas, which were not ruled by Saxons, tried to convert them to Christianity.

During the 7th century, these northern areas, especially Northumbria, became important places for learning. Monasteries acted like early schools. Smart people like Bede became very influential. In the 9th century, Alfred the Great worked to encourage people to read and get an education. He did a lot to promote the English language, even writing books himself. Alfred and the kings who came after him united and brought stability to most of southern Britain, which would eventually become England.

Late Medieval Society

After the Norman conquest in 1066, society seemed to stay the same for a few centuries. But slow, important changes were happening that people didn't fully understand until much later. The Norman lords spoke Norman French. To work for them or gain power, the English had to use the Anglo-Norman language that developed in England. This became an important language for government and writing. However, the English language was not replaced. After gaining many new words and grammar rules, English began to replace the language of the rulers. At the same time, England's population more than doubled between the Domesday Book survey and the end of the 13th century. This growth continued despite almost constant foreign wars, crusades, and occasional civil unrest.

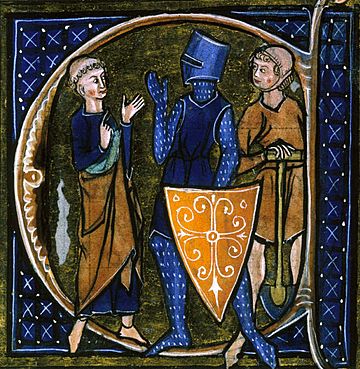

Historians often use the term Feudalism to describe medieval society. Simply put, a lord owned land or a fief. He allowed vassals to work this land in exchange for their military service. Most people were peasants who worked on the vassal's lands. This system, or something similar, was the basis of later medieval society. It probably existed in some form in England before the Norman conquest. But the Normans did a lot to set it up. They either replaced existing lords or became "overlords" above lords who now had less power. We learn a lot about these social structures from the Domesday Book, one of the best early surveys of its kind.

The Church's Role

The Crusades show how the church's power grew in medieval life. Some guess that as many as 40,000 clergy were ordained in the 13th century. This is also seen in the many cathedrals built across Europe at that time. These huge buildings often took several generations to finish. They created whole communities of artists and craftspeople, giving them jobs for life. The Church owned a quarter of all the land. Its monasteries owned large areas of land that peasants farmed.

Growth and Challenges

The two centuries from 1200 to 1400 (before the plague) were good times. The population grew quickly, from about 2 million to about 5 million. England was still mostly a rural society. Many farming changes, like crop rotation, kept the countryside profitable. Most people lived by farming. However, there were big differences in who owned land and the status of peasants. To feed the growing population, more land had to be farmed. Wild land was used, and people moved into forests, fens, and marshlands. "High farming" became more common. This meant landowners took direct control of their land, using hired workers instead of leasing it out. Books appeared with advice on the best farming methods. But the amount of food grown per acre didn't increase much. On good land, one acre might produce 17 bushels of wheat (compared to 73 bushels an acre in the 1960s).

After 1300, good times were less certain. This was due to too many people, not enough land, and tired soils. The Great Famine of 1315–1317 caused many deaths and severely hurt the English economy. Population growth stopped. The first outbreak of the Black Death in 1348 then killed about half the English population. But it left plenty of land for those who survived. Farming shrank, with higher wages, lower prices, and less profit. This led to the end of the old demesne system and the start of modern farming with cash rents for land. Wat Tyler's Peasants' Revolt in 1381 challenged the old feudal system. It also limited royal taxes for the next century.

Towns Grow

More people meant not only more crowded rural areas but also more and larger towns. Many new towns appeared, but most were small. Big cities like Lincoln, Norwich, and Thetford had 4,000–5,000 people. London grew from 10,000 to nearly 40,000 people, and York reached almost 10,000.

The 13th century saw a small industrial revolution. There was more use of wind power and changes in the wool industry. Wool was always important to the British economy. It was usually sent abroad to be processed. But now, it was often processed in England, creating many extra jobs. The export of cloth kept growing from the 14th century onwards. After the port of Calais was closed by the Spanish in the late 16th century, cloth became the main type of wool exported. Many people were finding different jobs and roles in English society. The growth of common law gave people more access to the law. The "commons" (ordinary people) also started to have a place in Parliament during Edward I of England's time.

Black Death's Impact

After many years of growth and slow change, one huge event dramatically changed British society. The Black Death in the mid-14th century almost cut the population in half. Whole villages were wiped out by the plague. But instead of destroying society, it actually made it stronger in some ways. Before the plague, there were too many workers and not enough jobs. Too many people were competing for limited resources. Afterwards, the drop in population meant that workers were scarce and were paid better. Peasants who had once been tied to a landowner's estate now had a reason to travel to areas without workers. This ability to move around, combined with peasants being able to charge much more for their work, started a shift from forced labor to wage earning. This signaled the decline of the feudal system.

The new freedoms for peasants worried the authorities a lot. They passed laws setting the maximum a peasant should be paid. But this didn't have much effect on wages. The first of several sumptuary laws were also made. These laws dictated exactly how people at every level of society should dress and what they could own. This was an effort to keep social classes separate. These new laws, plus a new poll tax (which was based on population numbers from before the plague), directly led to the Peasants' Revolt. Even though it was quickly stopped, the revolt was an early popular movement for change. It was a sign of bigger uprisings to come.

Chaucer's View

Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales gives a vivid picture of many different people in medieval society. However, these descriptions are mostly limited to the middle classes. The Wife of Bath is one especially lively character in the Tales. A few years later, a real woman named Margery Kempe showed in her autobiography that women played an important part in medieval society.

Tudor Society

Generally, the Tudor dynasty period was seen as quite stable compared to the constant wars before it. However, the English Reformation caused social conflict both inside and outside England. This had a big impact on how society was structured and on people's personalities.

Before Henry VIII broke them up and sold them, monasteries were important for social welfare. They gave alms (charity) and looked after the poor. Their disappearance meant the government had to take on this role. This led to the Poor Law of 1601. The monasteries were old and no longer the main educational or economic places in the country. After they were gone, many new grammar schools were founded. These, along with the earlier introduction of the printing press, helped more people learn to read and write.

Food and Farming

The farming changes that started in the 13th century sped up in the 16th century. Enclosure changed the open-field system and stopped many poor people from using land. Large areas of land that had once been "common" (shared by many people) were now being "enclosed" by the wealthy. This was mainly for very profitable sheep farming.

England's food supply was usually plentiful during most of this time. There were no famines. Bad harvests caused problems, but they were usually only in certain areas. The worst ones were in 1555–57 and 1596–98. In towns, the price of basic foods was set by law. In hard times, the size of the bread loaf sold by bakers was smaller.

Poor people mostly ate bread, cheese, milk, and beer. They had small amounts of meat, fish, and vegetables, and sometimes some fruit. Potatoes were just arriving at the end of this period and became more and more important. The typical poor farmer sold his best products at the market, keeping the cheap food for his family. Stale bread could be used to make bread puddings. Bread crumbs were used to thicken soups, stews, and sauces.

At a slightly higher social level, families ate a huge variety of meats. These included beef, mutton, veal, lamb, and pork, as well as chickens and ducks. A holiday goose was a special treat. Many people in the countryside and some in towns had small gardens. These produced vegetables like asparagus, cucumbers, spinach, lettuce, beans, cabbage, carrots, leeks, and peas. They also grew herbs for medicine and flavor. Some grew their own apricots, grapes, berries, apples, pears, plums, currants, and cherries. Families without a garden could trade with neighbors to get vegetables and fruits cheaply.

People discovered new foods (like the potato and tomato from the Americas) and developed new tastes during this time. More prosperous people enjoyed a wide variety of food and drink. This included exciting new drinks like tea, coffee, and chocolate. French and Italian chefs started working in country houses and palaces. They brought new ways of preparing food and new tastes. For example, the English developed a taste for sour foods, like oranges for the upper class. They also started using a lot of vinegar. Wealthy people paid more attention to their gardens, growing new fruits, vegetables, and herbs. Pasta, pastries, and dried mustard balls first appeared on tables. The apricot was a special treat at fancy banquets. Roast beef remained a main food for those who could afford it. Others ate a lot of bread and fish. Everyone, from all classes, enjoyed beer and rum.

At the wealthy end of society, manor houses and palaces had large, fancy meals. These were usually for many people and often included entertainment. They often celebrated religious festivals, weddings, alliances, and the queen's wishes.

17th Century Society

England was torn apart by civil war over religious issues. But generally, prosperity continued in both rural areas and the growing towns, as well as in the big city of London.

The English Civil War was more than just a fight between two religions. It was mostly about differences within the one Protestant religion. On one side was strict, fundamentalist Puritanism. On the other side was what they saw as the almost Catholic luxury of the Anglican church. Divisions also formed between common people and the wealthy, and between people in the countryside and city dwellers. It was a conflict that was sure to upset all parts of society. A common saying at the time was "the world turned upside down."

In 1660, the Stuart Restoration quickly brought back the high-church Stuarts. Public opinion reacted against the strictness of the Puritans. They had banned traditional fun like gambling, cockfights, theater, and even Christmas celebrations. The arrival of Charles II—known as The Merry Monarch—brought relief from the warlike and strict society people had lived in for several years. Theater returned, along with expensive fashions like the periwig. Even more expensive goods from overseas started to appear.

The British Empire grew quickly after 1600. Along with wealth returning to the country, expensive luxury items also appeared. Sugar and coffee from the East Indies, tea from India, and slaves (brought from Africa to the sugar colonies, along with some enslaved servants in England itself) were the backbone of imperial trade.

Near the end of the Stuart period, one in nine Englishmen lived in London. However, plagues were even deadlier in a crowded city. The only solution was to move to isolated rural areas. Isaac Newton from Cambridge University did this in 1664–66 when the Great Plague of London killed as many as 100,000 Londoners. The fast-growing city was the center of politics, high society, and business. As a major port and trade hub, goods from all over were for sale. Coffee houses became centers of business and social life. It has also been suggested that tea might have helped make Britain powerful. The antiseptic qualities of tea allowed people to live closer together, protecting them from germs. This might have made the Industrial Revolution possible. These products can be seen as the beginning of the consumer society. This society promoted trade and brought development and wealth to England.

Newspapers were new and soon became important for public discussion. The diarists of the time, like Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, are some of the best sources we have for everyday life in Restoration England. Coffee houses became numerous. They were places for middle-class men to meet, read papers, look at new books, gossip, and share opinions. Thomas Garway ran a coffee house in London from 1657 to 1722. He sold tea, tobacco, snuff, and sandwiches. Businessmen met there informally. The first furs from the Hudson's Bay Company were auctioned there.

The diet of the poor from 1660–1750 was mostly bread, cheese, milk, and beer, with small amounts of meat and vegetables. The more prosperous enjoyed a wide variety of food and drink, including tea, coffee, and chocolate.

Georgian Society

| Where people lived: City vs. Country, 1600–1801 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | City | Country (non-farm) | Farm |

| 1600 | 8% | 22% | 70% |

| 1700 | 17% | 28% | 55% |

| 1801 | 28% | 36% | 36% |

| Source: E.A. Wrigley, People, Cities and Wealth (1987) p 170 | |||

Farming Advances

Big improvements in farming made agriculture more productive. This freed up people to work in factories. The British Agricultural Revolution included new technologies like Jethro Tull's seed drill, which allowed for bigger harvests. The process of enclosure, which had been changing rural society since the Middle Ages, became unstoppable. The new machines needed much larger fields. This created the look of the British countryside we see today, with its patchwork of fields divided by hedgerows.

Industrial Revolution Begins

Historians usually say the Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the mid-18th century. Not only did existing cities grow, but small market towns like Manchester, Sheffield, and Leeds became cities just because so many people moved there.

Middle Class and Stability

The middle class grew quickly in the 18th century, especially in cities. At the top, lawyers were successful first, setting up special training and groups. Doctors soon followed. Merchants became wealthy through trade with the empire. By the 1790s, a self-proclaimed middle class had appeared, with its own social and cultural identity.

Thanks to growing national wealth, people moving up into the middle class, more people living in cities, and stable communities, Britain was relatively calm. This was certainly true compared to the revolutions and wars happening in the American colonies, France, and other nations at the time. The ideas of the French Revolution did not directly cause a huge revolution in British society. The loss of the American Colonies also did not greatly weaken or disrupt Great Britain.

Religion's Role

Historians have highlighted the importance of religion, including the dominance of the Anglican church. The Act of Toleration 1689 gave rights of free religious worship to the non-conformist Protestant groups that had appeared during the Civil War. Baptists, Congregationalists, Methodists, and Quakers were all allowed to pray freely. These groups took the chance to expand into the growing empire and set up in the Thirteen Colonies. There, they grew rapidly after the First Great Awakening.

In response to people's lack of religious and moral interest, Methodist preachers set up groups divided into "classes." These were small meetings where people were encouraged to confess their sins and support each other. They also took part in "love feasts," which allowed them to share their experiences and watch over each other's moral behavior. The success of Methodist revivals in reaching the poor and working classes focused their attention on spiritual goals rather than political complaints.

Victorian Era

The social changes during the Victorian era were huge and very important. They left their mark not only on the United Kingdom but on much of the world that was under Britain's influence in the 19th century. Some might even say these changes were bigger than the massive shifts in society during the 20th century. Many developments of the 20th century certainly started in the 19th. The technology of the Industrial Revolution had a great impact on society. Inventions not only created new industries for jobs, but the products and services also changed society.

England's population almost doubled from 16.8 million in 1851 to 30.5 million in 1901. Scotland's population also rose quickly. Ireland's population dropped sharply, mostly because of the Great Famine. At the same time, about 15 million people left the United Kingdom during the Victorian era. They settled mostly in the United States, Canada, and Australia. The rapidly growing British Empire not only attracted immigrants but also temporary administrators, soldiers, missionaries, and businessmen. When they returned, they talked about the Empire as part of a greater Britain.

Culturally, there was a shift away from the rationalism of the Georgian period. People moved towards romanticism and mysticism in religion, social values, and the arts. The era is often linked to the "Victorian" values of social and sexual restraint.

The situation of the poor changed a lot. The writings of two great English authors, Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, show the differences between life in the Georgian and Victorian eras. Both writers were fascinated by people, society, and everyday life. But in Austen's books, the poor are almost absent. This is mainly because they were still rural poor, far away and almost forgotten by the middle classes. For Dickens, just a few years later, the poor were his main topic. He had partly experienced their struggles himself. The poor were now an unavoidable part of city life, and their problems could not be ignored.

Industrialization brought large profits for business owners. Their success was a contrast not only to farm workers (who competed with imported food) but also to the rich landowners whose wealth was now less important than business wealth. The British class system created a complex hierarchy of people. It showed the differences between the new rich and the old rich, skilled and unskilled workers, and people in the countryside versus cities, among many others.

Some of the first attacks on industrialization were the Luddites destroying machines. But this was less about factory conditions and more about machines making linen much faster and cheaper than skilled laborers could by hand. The army was sent to areas where Luddites were active, like Lancashire and Yorkshire. For a time, there were more British soldiers controlling the Luddites than fighting Napoleon in Spain. The dirty, dangerous, and harsh conditions in many new Victorian factories and the communities around them became major sources of unhappiness. Workers began to form trade unions to get their working conditions improved.

The first unions were feared and mistrusted, and ways were found to ban them. The most famous case was that of the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1834. This was an early attempt at a union whose members were tried on a false charge, found guilty, and sent to Australia. The sentence was challenged, and they were released soon after. But unions were still threatened. It wasn't until the formation of the TUC in 1868 and the passing of the Trade Union Act 1871 that union membership became reasonably legal. Many laws were passed to improve working conditions, including the Ten Hours Act 1847 to reduce working hours. These laws led to the Factory Act 1901.

Many of these laws came about because of the problems caused by Britain's agricultural depression. From 1873 to 1896, many farmers and rural workers struggled to earn a steady income. With lower wheat prices and less productive land, many people in the countryside were looking for any hope of prosperity. Although the British Parliament gave significant help to farmers and laborers, many still complained that rents were too high, wages too low, and working hours too long for their income. As a result, many workers turned to unions to have their concerns heard. As the laws listed above show, they achieved some success.

Environmental and health standards improved throughout the Victorian era. Better nutrition may also have played a role, though this is debated. Sewage systems were improved, as was the quality of drinking water. With a healthier environment, diseases were caught less easily and did not spread as much. Technology also improved because people had more money to spend on medical technology. For example, techniques to prevent death in childbirth meant more women and children survived. This also led to more cures for diseases. However, a cholera epidemic happened in London in 1848–49, killing 14,137 people, and again in 1853, killing 10,738. This was blamed on the closing and replacement of cesspits by modern sewage systems.

Communication and Travel

Communication improved rapidly. Stage coaches, canal boats, steam ships, and most notably the railways all sped up the movement of people, goods, and ideas. New communication methods were very fast, if not instant. These included the telegraph, the telephone, and the trans-oceanic cable.

Trains opened up new places for leisure, especially seaside resorts. The Bank Holidays Act 1871 created a number of fixed holidays that the middle class could enjoy. Large numbers of people traveling to quiet fishing villages like Worthing, Brighton, Morecambe, and Scarborough began turning them into major tourist centers. People like Thomas Cook saw arranging domestic and foreign tourism as a good business idea. Steam ships like the SS Great Britain and SS Great Western made international travel more common. They also boosted trade, so that in Britain, it wasn't just luxury goods that were imported, but essentials like grain and meat from North America and Australia. One more important communication innovation was the Penny Black, the first postage stamp. It made postage a flat price regardless of distance.

Victorians were impressed by science and progress. They felt they could improve society in the same way they were improving technology. The model town of Saltaire was founded, along with others. It was a planned environment with good sanitation and many community, educational, and recreational facilities. However, it did not have a pub, which was seen as a place of disagreement. Similar sanitation reforms, prompted by the Public Health Acts of 1848 and 1869, were made in the crowded, dirty streets of existing cities. Soap was the main product shown in the relatively new world of advertising. Victorians also tried to improve society through many charities and relief organizations like the Salvation Army, the RSPCA, and the NSPCC. At the same time, many people like Florence Nightingale tried to reform public life. Another new institution was Robert Peel's "peelers," one of the earliest formal police forces.

Women and Family Life

Reformers organized many movements to get more rights for women. Voting rights did not come until the next century. The Married Women's Property Act 1882 meant that women did not lose their right to their own property when they got married. They could also divorce without fear of poverty, although divorce was frowned upon and very rare in the 19th century. It's a bit much to say Victorians "invented childhood," but they did see it as the most important stage of life. The trend was towards smaller families. This was probably because of the rise of modern families focused on their own members, along with lower infant deaths and longer lifespans. Laws reduced the working hours of children while raising the minimum working age. The passing of the Education Act 1870 set the basis for universal primary education.

In local government elections, unmarried women who paid rates (local taxes) got the right to vote in the Municipal Franchise Act 1869. This right was confirmed in the Local Government Act 1894 and extended to include some married women. By 1900, over 1 million women were registered to vote in local government elections in England.

20th Century Society

First World War's Impact

Edwardian ideals (from 1901–1914) were a bit more liberal. But what truly changed society was the Great War. The army was traditionally not a large employer in the nation. The regular army had 247,000 people at the start of the war. By 1918, there were about five million people in the army and the new Royal Air Force. The almost three million casualties were known as the "lost generation." Such numbers naturally left society scarred. But even so, some people felt their sacrifice was little regarded in Britain. Poems like Siegfried Sassoon's Blighters criticized the uninformed patriotism of the home front. Conscription brought people of many different classes, and also people from all over the empire, together. This mixing was seen as a great equalizer that would only speed up social change after the war.

The 1920s

The social reforms of the previous century continued into the twentieth. The Labour Party was formed in 1900, but it didn't achieve major success until the 1922 general election. David Lloyd George said after the World War that "the nation was now in a molten state." His Housing Act 1919 would lead to affordable council housing. This allowed people to move out of Victorian inner-city slums. The slums, though, remained for several more years. Trams were electrified long before many houses. The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women householders the right to vote. In 1928, full equal voting rights were achieved for all women.

After the War, many new food products became available to the typical household. Branded foods were advertised for their convenience. The shortage of servants was felt in the kitchen. But now, instead of an experienced cook spending hours on difficult custards and puddings, the ordinary housewife working alone could buy instant foods in jars, or powders that could be quickly mixed. Breakfast porridge from branded, more finely milled, oats could now be cooked in two minutes, not 20. American-style dry cereals began to challenge the porridge and bacon and eggs of the middle classes, and the bread and margarine of the poor. Street vendors were fewer. Shops were improved. The flies were gone, as were the open barrels of biscuits and pickles. Grocery and butcher shops carried more bottled and canned goods, as well as fresher meat, fish, and vegetables. While wartime shipping shortages had sharply limited choices, the 1920s saw many new kinds of foods—especially fruits—imported from around the world, along with better quality, packaging, and hygiene. Middle-class households now had ice boxes or electric refrigerators. This allowed for better storage and the convenience of buying in larger quantities.

The Great Depression

The relatively good times of the 1920s gave way by 1930 to a depression. This was part of a worldwide crisis.

The north of England and Wales were hit particularly hard. Unemployment reached 70% in some areas. The General Strike was called in 1926 to support miners and their falling wages, but it failed. The strike marked the start of the slow decline of the British coal industry. In 1936, two hundred unemployed men walked from Jarrow to London. They wanted to show the struggles of the industrial poor. But the Jarrow March had little impact. Industrial prospects didn't improve until 1940. George Orwell's book The Road to Wigan Pier gives a bleak overview of the hardships of that time.

World War II: 1939–45

The war was a "people's war" that involved every political party, social class, region, and interest, with surprisingly little disagreement. It started with a "phony war" with little fighting. Fear of bombing led to women and children being moved from London and other cities likely to be bombed. They were evacuated to the countryside. Most returned some months later and stayed in the cities until the end of the war. There were half the number of military deaths in this war than the last. But improvements in air warfare meant there were many more civilian deaths. A foreign war seemed much closer to home. The early years of the war, when Britain "stood alone," and the "Blitz spirit" that developed as Britain suffered under air attacks, helped bring the nation together after the divisions of the previous decade. Campaigns like "Dig for Victory" helped give the nation a common purpose. The focus on farming to feed the nation gave some people their first experience of the countryside. Women played an important part in the war effort as the Land Girls.

Half a million women served in the armed forces. Princess Elizabeth, the future queen, wore the ATS soldier's uniform as a lorry driver.

Since 1945

Austerity: 1945–51

The Labour Party victory in 1945 showed people's pent-up frustrations. There was a strong feeling that all Britons had joined in a "People's War" and all deserved a reward. But the Treasury was almost bankrupt, and Labour's nationalization programs were expensive. Pre-war levels of prosperity didn't return until the 1950s. This period was called the Age of Austerity. The most important reform was the founding of the National Health Service on July 5, 1948. It promised to give "cradle to grave" care for everyone in the country, no matter their income.

Wartime rationing continued and was even extended to bread. During the war, the government banned ice cream and rationed sweets, like chocolates and candies. Sweets were rationed until 1954. Most people complained, but for the poorest, rationing was good. Their rationed diet had more nutritional value than their pre-war diet. Housewives organized to oppose the austerity. The Conservatives saw their chance and rebuilt their popularity by attacking socialism, austerity, rationing, and economic controls. They were back in power by 1951.

Prosperous 1950s

As good times returned after 1950, Britons became more focused on their families. Leisure activities became more available to more people after the war. Holiday camps, which first opened in the 1930s, became popular holiday spots in the 1950s. People increasingly had money to pursue their personal hobbies. The BBC's early television service got a big boost in 1953 with the coronation of Elizabeth II. It attracted an estimated audience of twenty million. This encouraged middle-class people to buy televisions. In 1950, 1% owned television sets; by 1965, 75% did. As austerity faded after 1950 and consumer demand kept growing, the Labour Party hurt itself by avoiding consumerism. They saw it as the opposite of the socialism they wanted.

Small neighborhood stores were increasingly replaced by chain stores and shopping centres. These offered a wide variety of goods, smart advertising, and frequent sales. Cars were becoming a significant part of British life. This led to city-center traffic jams and "ribbon developments" (houses built in long lines) along many major roads. These problems led to the idea of the green belt to protect the countryside, which was at risk from new housing developments.

The 1960s

The 1960s saw big changes in attitudes and values, led by young people. It was a worldwide trend, and British rock musicians, especially The Beatles, played a global role.

The 1960s were a time of less respect for the "establishment" (the powerful groups in society). There was a boom in satire led by people who were willing to criticize their elders. Pop music became a dominant way for young people to express themselves. Bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were seen as leaders of youth culture. Youth-based subcultures like the mods, rockers, hippies, and skinheads became more visible.

Changes in education led to the effective removal of the grammar school. The rise of the comprehensive school aimed to create a more equal educational system. More and more people were going into higher education.

In the 1950s and 1960s, immigration to the United Kingdom began to increase. People mainly came from former British colonies in the Caribbean, India, and Pakistan. This led to racism. Dire predictions were made about the effect of these new arrivals on British society (most famously Enoch Powell's Rivers of Blood speech). Tension led to a few race riots. In the longer term, many people with different cultures have successfully integrated into the country. Some have risen to high positions.

The 1980s

One important change during the 1980s was the chance given to many people to buy their council houses. This resulted in many more people becoming property owners in a "stakeholder society." At the same time, Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher weakened her bitter enemy, the trade unions.

The environmentalism movements of the 1980s reduced the focus on intensive farming. They promoted organic farming and conservation of the countryside.

Religious practice declined noticeably in Britain during the second half of the 20th century. This happened even with the growth of non-Christian religions due to immigration and travel (see Islam in the UK). Church of England attendance has dropped particularly, although energetic churches like Elim and AOG are growing. The movement to Keep Sunday Special seemed to have lost by the beginning of the 21st century.

1990s and the New Millennium

Following the return of economic liberalism in the 1980s, the last decade of the 20th century was known for a greater acceptance of social liberalism within British society. This is largely thought to be due to the greater influence of the generation born in the socially changing 1960s.

The death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997 showed how social attitudes towards mourning had changed. The huge public outpouring of grief that marked the days after her death was seen as reflecting a change in the national mood.

Growing differences in wealth between those who benefited and those "left behind" from the decline of industries and globalization of the economy were seen as a main reason for the surprise victory of the "leave" campaign in the 2016 European Union membership referendum. This started a wider discussion about the emergence of "two countries" within England. These represented very different social attitudes and outlooks.

|

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |