Religion in Medieval England facts for kids

Religion in Medieval England covers all the ways people practiced their faith from the end of Roman rule in the 400s to the start of the Tudor family's rule in the late 1400s. When the Romans left, Christianity mostly disappeared in eastern England. This happened as Germanic settlers brought their own pagan beliefs.

Christianity began to return in the late 500s and 600s. Pope Gregory I sent missionaries who slowly converted most of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. At the same time, monks from Scotland and Ireland were active in northern England. By the end of the 600s, most of England was Christian. However, there were many different local customs and ceremonies. The Viking invasions in the 700s and 800s brought paganism back to North-East England. This led to another wave of Christian conversions.

The spread of Christianity led to many new churches and monasteries being built. These were the main centers of the church. Cathedrals were also built. Viking raids in the 800s badly damaged these places. Later, kings from Wessex helped reform the church. They promoted the Benedictine rule, which was popular in Europe. The 1066 Norman conquest brought new church leaders from Normandy and France. Some of these leaders kept parts of the old Anglo-Saxon religious system. Others brought new practices from Normandy.

New religious groups became popular. The French Cluniac order became well-known. The Augustinians spread quickly from the early 1100s. Later in that century, the Cistercians arrived in England. The Dominican and Franciscan friars came to England in the 1220s. Military religious orders, popular across Europe, also gained followers.

The Church and the English government were very close throughout the Middle Ages. Bishops and important monastery leaders played a big part in running the country. After the Norman Conquest, kings and archbishops often disagreed about who should appoint church leaders and what religious rules should be. By the early 1200s, the church had mostly won its fight for independence. Pilgrimages were a popular religious activity. Taking part in the Crusades was also seen as a type of pilgrimage. England played a big role in the Second, Third, and Fifth Crusades. In the 1380s, John Wycliffe challenged some traditional church teachings.

Contents

History of Religion in England

Early Christianity and Paganism

From Roman Times to Anglo-Saxons

By 380 AD, Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire. The church in Roman Britain had bishops and priests. Many old pagan shrines were changed into Christian ones. Few pagan sites were still active by the 400s. After the 400s, the Roman system collapsed. Germanic pagans invaded, and formal church organization disappeared in Britain. These Anglo-Saxons brought their own gods, like Woden, Thunor, and Tiw. Their names are still seen in some English place names today. Even with new pagan beliefs, Christian groups still lived in western areas like Gloucestershire and Somerset.

How England Became Christian Again

The move back to Christianity started in the late 500s and 600s. This was helped by the conversion of the Franks in Northern France, who had a lot of influence in England. Pope Gregory I sent missionaries, known as the Gregorian mission. They converted King Æthelberht of Kent and his family. This began the process of converting Kent. Augustine became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. He started building new churches in the South-East, often reusing old pagan shrines.

Kings Oswald and Oswiu of Northumbria were converted in the 630s and 640s by Scottish missionaries. This wave of change continued through the mid-600s across other kingdoms. By the end of the 600s, most of England was Christian. However, there were still many different local ways of practicing religion. This new Christianity fit the Anglo-Saxons' military culture. As kings converted, they used Christianity to justify wars against remaining pagan kingdoms. Christian saints were also seen as having warrior-like qualities.

Organizing the English Church

Over the next few years, the English Church was organized. It was under the Pope's authority. The church was divided into two main areas, called ecclesiastical provinces. Each was led by an Archbishop. The northern area was based in York, and the southern area in Canterbury. The Archbishop of Canterbury had final authority over the whole English Church. This division between the Province of Canterbury and the Province of York remains today.

Pope Gregory gave Augustine authority over the bishops of the local Celtic church. But the Celtic bishops refused to work with the Roman missionaries. The Celtic and Latin churches disagreed on several things. The most important was the date of Easter. There were also differences in baptism customs and the haircut (tonsure) worn by monks.

King Oswald of Northumbria supported the Celtic Christian way, as practiced at Iona Abbey. Saint Aidan started a monastery at Lindisfarne. Under King Oswiu of Northumbria, tensions grew between followers of the Latin and Celtic traditions. To solve this, Oswiu called the Synod of Whitby in 664. Both sides presented their arguments. The king decided that Northumbria would follow the Latin tradition. He based his decision on authority: the successors of Saint Peter (the Popes) were more important than the successors of Saint Columba.

The Council of Hertford in 673 was the first meeting of bishops from all over England. They agreed on rules to make things more uniform. One rule was that English bishops should hold an annual council at Clovesho. It also confirmed that Latin Church traditions should be followed over Celtic ones. The Celtic traditions had been strong in the north and west.

A big change happened in the English church in the late 700s. King Offa of Mercia wanted his own kingdom to have an archbishop. The Archbishop of Canterbury was also a powerful Kentish noble. In 787, a church council, with two papal representatives, made the Diocese of Lichfield an archbishopric. So, England had three provinces: York, Lichfield, and Canterbury. But this arrangement ended in 803. Lichfield became part of the Province of Canterbury again.

How Parishes Developed

At first, the diocese was the only administrative unit in the Anglo-Saxon church. The bishop served the diocese from a cathedral town. He had help from a group of priests called the bishop's familia. These priests would baptize, teach, and visit distant parts of the diocese. Familiae were also placed in other important settlements, called minsters.

The parish system grew out of manorialism. A parish church was a private church built by the lord of the manor. The lord also chose the parish priest. The priest supported himself by farming his glebe (church land). He also received support from the parishioners. The most important support was the tithe. This was the right to collect one-tenth of all produce from land or animals. At first, the tithe was a voluntary gift. But by the 900s, the church made it a required tax.

Vikings and New Conversions

The Viking invasions in the 700s and 800s brought paganism back to North-East England. This led to another wave of conversions to Christianity. Scandinavian beliefs were similar to other Germanic groups. They had gods like Odin, Thor, and Ullr. They also believed in a final, huge battle called Ragnarok.

The Norse settlers in England converted fairly quickly. They blended their beliefs with Christianity after taking over York. The Archbishop of York had survived the invasion. By the early 900s, the conversion process was mostly complete. This allowed England's church leaders to talk with the Viking warlords. As the Norse in Scandinavia started to convert, many rulers there asked missionaries from England for help.

A Unified Christian Kingdom

Alfred the Great of Wessex and his successors fought back against the Anglo-Saxons. This led to the creation of a single Kingdom of England. The king was seen as the head of the church. He was also called "the vicar of Christ among a Christian folk." Bishops were chosen by the king. They were often picked from royal chaplains or monasteries. The chosen bishop was then approved by church leaders and became a bishop.

Appointing an archbishop was more complex. It needed approval from the pope. The Archbishop of Canterbury had to travel to Rome. There, he received the pallium, a symbol of his office. These trips to Rome and the payments that went with them, like Peter's Pence, were sometimes a source of disagreement.

After much of England converted in the 500s and 600s, many local churches were built. English monasteries were the main base for the church. Local rulers often supported them. Monasteries took different forms. Some were mixed communities led by abbesses. Others were bishop-led groups of monks. Some were formed around married priests and their families. Cathedrals were built and staffed either by secular canons (like in Europe) or, uniquely in England, by groups of monks.

Viking raids in the 800s badly affected these institutions. Nobles also took over church lands. By the early 900s, monasteries had much less land, money, and religious work. Reforms followed under English kings. They promoted the Benedictine rule, which was popular in Europe. When Edgar the Peaceful became king in 959, there was only one Benedictine monastery in England. This was Glastonbury Abbey, led by Dunstan. The king and Dunstan, who became Archbishop of Canterbury, worked together. They promoted Benedictine Reform across England.

Monasteries were national institutions. They owned land throughout England. They were controlled and funded by the king. This helped reduce the power of local nobles. A reformed network of about 40 monasteries helped the king regain control over the reconquered Danelaw.

By the 900s, the parish system was well established. The parish church was still owned by a local lord. But in towns and the Danelaw, people had gained ownership. Parish priests were usually local men with basic education. Many were married, especially in the North. But priestly celibacy (priests not marrying) was becoming more common. For those who could read, there were many religious books in English. Examples include the Blickling homilies and the writings of Ælfric.

In 1000, England had eighteen dioceses. To help bishops oversee parishes and monasteries, the job of archdeacon was created. Once a year, the bishop would call parish priests to the cathedral for a meeting.

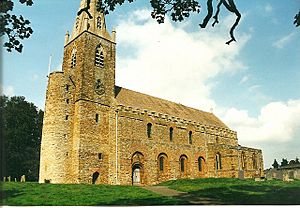

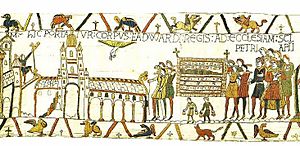

In the 1050s, Edward the Confessor rebuilt Westminster Abbey as his burial place. It was based on Norman churches and was the largest church in England. The king chose to be buried at Westminster instead of the traditional site of Winchester. This was part of London becoming the center of English politics.

The Church After the Norman Conquest

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, invaded England with the Pope's support. The Pope also told English clergy to obey William. Control over the church was a key part of the Norman Conquest. In 1070, two papal representatives came to England. They were there to reform the church. They removed bishops who were seen as unfit or who had been appointed by rival popes. This helped William remove church officials he didn't trust. After this, only two English bishops remained. Lanfranc of Bec became Archbishop of Canterbury. Thomas of Bayeux became Archbishop of York.

Some Norman and French church leaders adopted parts of the old Anglo-Saxon religious system. Others brought new practices from Normandy. Large areas of English land were given to monasteries in Normandy. This allowed them to create smaller churches and monastic cells across England. Monasteries became part of the feudal system. Their land ownership was linked to providing military support to the king.

The Normans kept the Anglo-Saxon idea of monastic cathedral communities. Within 70 years, most English cathedrals were controlled by monks. However, the new rulers rebuilt every English cathedral to some extent. English bishops remained powerful figures. In the early 1100s, they raised armies against Scottish invaders. They also built many castles across the country.

New religious orders began to arrive in England. As ties to Normandy weakened, the French Cluniac order became popular. Their houses were set up in England. The Augustinians spread quickly from the early 1100s. Later in the century, the Cistercians reached England. They built houses with a stricter way of life, like the great abbeys of Rievaulx and Fountains.

By 1215, England had over 600 monastic communities. But new donations slowed down in the 1200s. This caused financial problems for many places. The Dominican and Franciscan friars arrived in England in the 1220s. By the end of the 1200s, they had 150 friaries. These mendicant orders (who lived by begging) quickly became popular, especially in towns. They greatly influenced local preaching. Religious military orders, popular across Europe from the 1100s, also gained property in England. These included the Templars, Teutonic Knights, and Hospitallers.

Beliefs and Practices

Inside a Medieval Church

Medieval churches had two main parts. The nave was where the people gathered. The chancel was at the east end of the building. The chancel was the most sacred part. It included the sanctuary where the main altar was. A rood screen stood under the chancel arch. It separated the chancel from the nave. The rood screen was made of wood. It had a door and gaps where people could look into the chancel. This screen showed the division between the clergy (priests) and the laity (regular people).

Above the rood screen was the rood or crucifix. This was a life-sized image of Christ on the cross. It was flanked by carved images of the Virgin Mary and the apostle John.

Church walls had colorful paintings. These showed important Christian ideas like creation, incarnation, atonement, penance, purgatory, and judgment. Most people could not read. So, these images were like "books for laymen." One such image was the doom painting above the chancel arch. The doom painting showed the Last Judgment. It depicted Christ in glory, the dead rising, the saved going to Heaven, and the damned being dragged to Hell.

Mass and Worship

The Mass was central to medieval religion. During Mass, the priest offered bread and wine on the altar. According to the teaching of transubstantiation, the bread and wine miraculously changed into the body and blood of Christ. This meant that when Christians ate the special bread (called the host), Christ became part of them. The Church also taught that the Mass was a sacrifice. It was the same sacrifice as Christ on the cross. It was also a way to receive forgiveness, salvation, and healing.

The priest spoke or sang the Mass entirely in Latin. Few people understood Latin. Also, the priest often whispered or mumbled the service. This meant people in the nave could not hear. When responses were needed, the choir or helpers in the chancel provided them. Any singing was done by choirs in plainchant or polyphony. While the priest performed the service, the regular people prayed and moved around the building. Few churches had pews. They could pray at a side altar dedicated to a specific saint. Those who could read might use a Book of Hours. This book adapted the daily monastic prayers for use by everyday people.

The most important part of the Mass was the elevation of the host. This allowed the people to worship the body of Christ. Many believed that looking at the host protected them from sudden death for the rest of that day. The priest always took communion during Mass. But regular people only received communion at Easter. To prepare for communion, people had to fast. They also had to confess all their sins to a priest. The priest would then give them penance and forgive their sins. The person receiving communion would enter the chancel through the rood screen. They would kneel before the priest. The priest placed the host directly into their mouth so their hands would not touch it. Regular people never received the sacramental wine. Only the priest received both the bread and wine.

Sermons were not usually preached at Mass. Most priests were not trained preachers. Clergy needed a special license from the bishop to preach. Parishes sometimes heard sermons from visiting friars or other preachers. Each parish was supposed to hear a sermon at least four times a year. But whether this happened depended on how isolated the parish was.

Pilgrimages

Pilgrimages were a popular religious practice in Medieval England. Pilgrims usually traveled short distances to a shrine or a specific church. They went either to do penance for a sin or to seek relief from an illness. Some pilgrims traveled further, to more distant sites in Britain. A few even went to Europe.

During the Anglo-Saxon period, many shrines were built on former pagan sites. These became popular pilgrimage spots. Other pilgrims visited important monasteries and learning centers. Important nobles or kings would travel to Rome. This was a popular destination from the 600s. Sometimes these trips were a way to leave the country for political reasons.

Under the Normans, religious places with important shrines promoted themselves as pilgrimage destinations. These included Glastonbury, Canterbury, and Winchester. They highlighted the historic miracles linked to their sites. Collecting relics became important for ambitious institutions. Relics were believed to have healing powers and gave status to a site. By the 1100s, reports of miracles by local saints after their deaths became common in England. This made pilgrimages to important relics even more appealing.

Major shrines in the late Middle Ages included those of Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. Others were Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey, Hugh of Lincoln, William of York, and Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Taking part in the Crusades was also seen as a type of pilgrimage. The same Latin word, peregrinatio, was sometimes used for both. English involvement in the First Crusade (1095-1099) was limited. But England played a big part in the Second, Third, and Fifth Crusades over the next two centuries. Many crusaders left for the Levant (the Middle East) in between these main crusades. The idea of a pilgrimage to Jerusalem was not new in England. The idea of religiously justified warfare dated back to Anglo-Saxon times. Many who decided to go on a Crusade never actually left. Often, this was because they did not have enough money for the journey. Raising money usually meant crusaders selling or mortgaging their lands and belongings. This affected their families and sometimes the economy.

Lollardy: A New Challenge

In the 1380s, some new ideas challenged the traditional teachings of the Church. These came from John Wycliffe, a scholar at Oxford University. Wycliffe believed that scripture (the Bible) was the best guide to understanding God's plans. He argued that the church's fancy ceremonies, its wealth, and the role of senior churchmen in government distracted from studying the Bible.

After Wycliffe's death in 1384, a group of people, including many nobles, followed his ideas. They tried to pass a Parliamentary bill in 1395. The authorities quickly condemned this movement and called it "Lollardy". English bishops were told to control and fight this trend. They did this by stopping Lollard preachers and making sure proper sermons were taught in local churches.

By the early 1400s, fighting Lollard teachings became a major political issue. Henry IV and his Lancastrian followers strongly supported this. They used the power of both the church and the state to fight this heresy (beliefs against official church teaching). Things came to a head in 1414, at the start of Henry V's reign. Sir John Oldcastle, a suspected Lollard, escaped from prison. This led to a planned uprising in London. However, the authorities found out about the plans and arrested the plotters. This resulted in more trials and persecutions. Oldcastle was caught and executed in 1417. Lollardy continued as a secret, smaller group.

Church and Government

The Church had a very close relationship with the English government throughout the Middle Ages. Bishops and important monastery leaders played a big part in running the country. They had key roles on the king's council. Bishops often oversaw towns and cities. They managed local taxes and government. This became difficult during the Viking attacks of the 800s. In places like Worcester, local bishops made new agreements with local nobles. They traded some authority and money for help with defense.

The early English church had disagreements about doctrine (beliefs). The Synod of Whitby in 664 tried to fix this. Some issues were resolved. But arguments between the archbishops of Canterbury and York about who had more power across Britain started soon after. These arguments continued for most of the medieval period.

William the Conqueror gained the Church's support for his invasion of England. He promised to reform the church. William promoted celibacy among the clergy (priests not marrying). He also gave church courts more power. But he also reduced the Church's direct links to Rome. He made it more accountable to the king. Tensions arose between these practices and the reforming movement of Pope Gregory VII. This movement wanted more independence for the clergy from royal power. It also condemned simony (buying or selling church offices). It promoted more influence for the Pope in church matters.

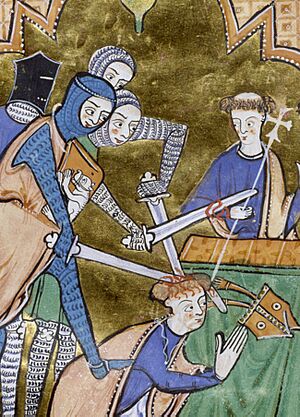

Even though bishops played a big part in royal government, tensions grew between the kings of England and key leaders in the English Church. Kings and archbishops often clashed over who should appoint church officials and what religious rules should be. Several archbishops, including Anselm, Theobald of Bec, Thomas Becket, and Stephen Langton, were forced into exile. Some were arrested by royal knights, or even killed. By the early 1200s, however, the church had largely won its fight for independence. It answered almost entirely to Rome.

Bishops had many responsibilities outside of religion. As tenants-in-chief of the king, they had to provide a certain number of armed knights for the king's army. They were not expected to fight themselves. But several bishops became active military leaders. For example, Thurstan, Archbishop of York, gathered the army that defeated the Scots at the Battle of the Standard in 1138. Bishops were also in charge of managing their huge estates. They presided over courts that dealt with civil disputes within their lands. They also had to attend royal councils. When the Parliament of England developed in the 1200s, the two archbishops and nineteen bishops had to take their seats in the House of Lords. The abbots and priors of the largest religious houses also joined them. Together, they were known as the Lords Spiritual.

Jewish Communities in England

The first large Jewish population in England arrived after the Norman Conquest. They reportedly came from Rouen in Normandy. By the mid-1100s, there were Jewish communities in most of England's major cities. There were violent attacks and riots against Jews in several cities. However, Jews were supposed to be protected by the King. This was because they were important for the country's finances.

But in 1275, King Edward I passed the Statute of Jewry. This law forced Jews to wear a yellow badge. It also made usury illegal. Usury was the lending of money for interest. This was the main way many Jewish families earned money. After growing persecution by the state and attempts to force them to convert to Christianity, Edward finally expelled all Jews from England in 1290.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |