Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain facts for kids

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain was a big change in the language and culture of most of what we now call England. It shifted from Romano-British (like the Romans) to Germanic ways. The Germanic-speaking people who came to Britain, from different places, eventually formed a shared identity as Anglo-Saxons. This change mainly happened from the mid-400s to the early 600s. It followed the end of Roman rule in Britain around the year 410.

After this settlement, new Anglo-Saxon kingdoms formed in the south and east of Britain. This area later became modern England and parts of Scotland. What exactly happened during this time is still being studied. Experts are still asking about how many people moved, when they arrived, and what happened to the people who already lived in England.

We have some clues from old writings, archaeological finds, and even DNA information. The few old writings talk about fighting between the newcomers and the native people. They describe violence, destruction, and the native Romano-British people fleeing. Also, the Old English language shows very little influence from British Celtic or British Latin languages. These clues once made many historians think that a huge number of Germanic people moved in. They believed that much of England was emptied of its original people. If this was true, then the genes of later English people would mostly come from these Germanic migrants.

However, another idea is that fewer migrants came, perhaps mainly a group of powerful warriors. This idea suggests that the newcomers became politically and socially strong. With some intermarriage, they slowly influenced the native people to adopt their language and way of life. Archaeologists have found that how people settled and used land didn't change much from Roman times. But the everyday objects they used changed a lot. This idea suggests that the ancestry of Anglo-Saxon and modern English people would mostly come from the original Romano-British people.

Still, if these newcomers became a powerful group and mostly married within their own group, they could have had more children who survived. This is called the 'apartheid theory'. In this case, the main genes in later Anglo-Saxon England could still come from a smaller number of Germanic migrants. This theory has been debated. But recent DNA studies in the late 2010s and early 2020s have shown that more people moved from Germanic-speaking areas than the 'small migration' theory suggested. These studies also found that marriages between native Britons and immigrants were more common than the 'apartheid theory' proposed.

Contents

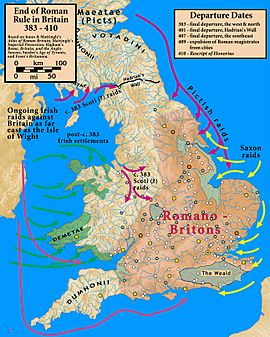

Why Did Romans Leave Britain?

By the year 400, the Roman provinces in Britain were a distant part of the Roman Empire. They were sometimes lost to rebellions or invasions. But they were always taken back by the Romans. This pattern of losing and regaining control stopped over the next ten years. Around 410, Roman power in Britain ended. This period is often called "sub-Roman".

People used to think this time was just about decline and collapse. But evidence from places like Verulamium shows that city-like rebuilding, even with piped water, continued into the late 400s. At Silchester, signs of people living there after the Romans are found until about 500. At Wroxeter, new Roman-style baths were built.

Writings from Saint Patrick and Gildas (who we'll talk about later) show that people in Britain still knew how to read and write Latin. They also kept Roman education, learning, law, and Christianity among the important people. This lasted through most of the 400s and 500s. Gildas's writings also suggest the economy was doing well without Roman taxes. He complained about people living too luxuriously. In the mid-400s, Anglo-Saxons started appearing in Britain, which still seemed to be working in a Roman way.

What Do Old Writings Tell Us?

When we look at old writings about the Anglo-Saxon settlement, we assume that words like Angles, Saxons, or Anglo-Saxon mean the same thing everywhere. But giving people ethnic labels like "Anglo-Saxon" is tricky. The term "Anglo-Saxon" only started being used in the 700s. It helped tell apart the "Germanic" groups in Britain from those on the European continent.

Early Records of Change

The Chronica Gallica of 452 (a record from Gaul) says for the year 441: "The British provinces, which had suffered many defeats, are now under Saxon rule." This record was written far from Britain. So, the exact dates for events in the 400s, especially before 446, are not certain. Much of the dating for this time comes from Bede, an English monk and scholar (672/673–735). In his book Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede tried to figure out dates for early Anglo-Saxon history.

Bede is seen as Britain's first true historian. He listed his sources and dated events. Because of this, we know he relied a lot on De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae by Gildas, a church leader from the 500s. Historians have found Gildas's dates to be unreliable. So, Bede's later dates, even if they seem to disagree with the Gallic Chronicles, don't make the chronicle less important as an old source. The chronicle groups Britain with four other Roman areas that came under 'Germanic' control around the same time. This list was meant to explain the end of the Roman Empire in the west. These four areas had similar stories. Roman authorities gave them over to "barbarian" power.

Procopius, writing in the mid-500s, said that Britain was settled by three groups: the Angili, Frissones, and Brittones. Each group had its own king. He also said that after Constantine III was overthrown in 411, "the Romans never got Britain back. It stayed under tyrants from then on."

Gildas's Story: De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

In Gildas's book from the 500s, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, he wrote about the state of Britain. He saw the Saxons as enemies from overseas. He believed they brought deserved punishment to the local kings.

Here's how Gildas described the events:

- After asking for help from Aëtius (known as the Groans of the Britons), the Britons faced famine and attacks from the Picts and Scoti. Some fought back well, leading to a time of peace.

- This peace led to too much luxury and self-indulgence.

- The Picts and Scoti threatened to attack again. A council decided to give land in the east to the Saxons. This was part of a treaty, a foedus. The Saxons would defend the Britons in exchange for food. This kind of deal was common in late Roman times.

- The Saxon foederati (allied troops) first complained their food supplies were not enough. Then they threatened to break the treaty, which they did. They spread their attack "from sea to sea."

- This war, called the "War of the Saxon Federates," ended about 20–30 years later. It was shortly after the siege at Mons Badonicus. This was about 40 years before Gildas was born.

- A peace agreement was made with the Saxons. They went back to their eastern home. Gildas called this a "grievous divorce from the barbarians." This "divorce settlement" was worse for the Britons. It included paying tribute to the people in the east (the Saxons).

Gildas used the correct Roman term for the Saxons, foederati. These were people who came to Britain under a common treaty system. Gildas called them Saxons, which was probably the common British name for the settlers. Gildas also used the word patria (homeland) when talking about the Saxons. This suggests that some Saxons might have been seen as native to Britain by then.

For Gildas, Britain meant the whole island. He wasn't focused on ethnicity or language. He cared about the faith and actions of the leaders. His historical details were "side effects" of him talking about royal sins. Gildas used strong, dramatic language. For example, he called the Saxons "villains" and "enemies," led by a "Devil-father." Yet, Gildas said he lived through a time of "external peace." This peace brought "unjust rule."

Gildas's comments showed his worry about his countrymen's weakness and their internal fighting. He said, "it was always true of this people (as it is now) that it was weak in beating off the weapons of the enemy, but strong in putting up with civil war and the burden of sin." But after the War of the Saxon Federates, Gildas didn't seem to know about any mass killings, huge exoduses, or widespread slavery. Gildas mentioned that Britain's spiritual life suffered because the country was divided. This stopped citizens from visiting holy shrines. Control had been given to the Saxons, even access to these shrines. The church was now 'tributary', and the nobles had lost their power to govern.

Gildas described the corruption of the leaders: "Britain has kings but they are tyrants; she has judges but they are wicked." He often mentioned broken promises and unfair judgments for ordinary people. British leadership everywhere was immoral and caused the "ruin of Britain."

Bede's History: Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

Bede used Gildas and other sources for his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, written around 731. Bede said the migrants were Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. He reported that the Saxons came from Old Saxony (Northern Germany). The Angles came from 'Anglia', which was between the Saxon and Jute homelands. Anglia is usually thought to be the old Schleswig-Holstein Province (near modern Danish-German border). The coast between the Elbe and Weser rivers was the Saxon area. Jutland, a peninsula in Denmark, was the Jutes' home.

Bede seemed to describe three stages of settlement:

- Exploration: Mercenaries (soldiers for hire) came to protect the local people.

- Migration: A large number of people moved, suggesting 'Anglus' (Anglia) was deserted.

- Establishment: Anglo-Saxons started controlling areas.

Bede's view of Britons often made them seem like oppressed subjects of the Anglo-Saxons. This idea has been used by some to suggest theories of invasion and settlement involving mass killings, forced migration, and slavery. Bede's description of Britons was influenced by Gildas. Gildas saw the Saxons as God's punishment. Bede took this further. He showed the pagan Anglo-Saxons not as a punishment, but as agents of Britain's "redemption." So, any harsh treatment was necessary and planned by God, because the Britons had lost God's favor.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a historical record of events in Anglo-Saxon England. It was kept from the late 800s to the mid-1100s. It's a collection of yearly records. Some entries were updated more than 600 years after the events they describe. They contain various entries that support the idea of a migration, the Anglo-Saxon leaders, and important historical events.

The earliest events in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle were written down centuries after they happened. Experts like Barbara Yorke have pointed out that many parts of the Chronicle for the 400s and early 500s don't seem like reliable year-by-year records. Some information from the early period might have a bit of truth, if we ignore the obvious made-up parts. For example, the events about Ælle of Sussex seem possible, even if the dates are uncertain. However, using the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as proof for the Anglo-Saxon settlement is tricky. It depends a lot on which entries we believe are true.

What Does Language Tell Us?

Understanding how language changed, especially how Old English became common, is very important for the Anglo-Saxon settlement story. Most experts now agree that English spread because a small group of Germanic-speaking immigrants became politically and socially powerful. This happened as Latin lost its importance after the Roman economy and government collapsed.

Clues from Words and Names

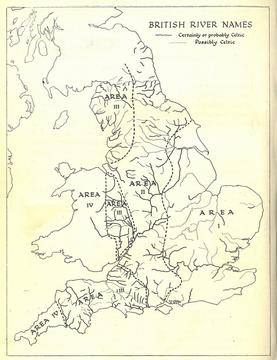

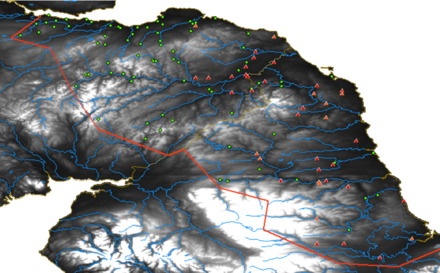

All language evidence from Roman Britain suggests that most people spoke British Celtic and/or British Latin. But by the 700s, when we have more evidence, it's clear that Old English was the main language in what is now eastern and southern England. Old English came from West Germanic languages spoken in what is now the Netherlands and northern Germany. Old English then kept spreading west and north. This is very different from places like France or Spain after the Romans left. There, Germanic invaders slowly switched to the local languages. Old English shows very little influence from Celtic or spoken Latin. For example, there are almost no English words that come from Brittonic.

Also, except in Cornwall, most place-names in England can easily be traced back to Old English (or Old Norse from later Viking influence). This shows how dominant English became across post-Roman England. Recent studies have found more Brittonic or Latin place-names in England than once thought. But still, Brittonic and Latin place-names are extremely rare in eastern England. Even in the western half, they are a tiny minority.

The Language Debate

Until the late 1900s, scholars usually explained the lack of Celtic influence on English by saying that Germanic invaders killed, chased away, or enslaved the previous inhabitants. This idea was supported by reading Gildas and Bede without questioning them. Some experts still support this idea.

But today, many experts, influenced by studies of how languages interact, believe that a fairly small number of Old English speakers could have become politically dominant. This could have led many Britons to adopt Old English. This would leave little trace of the language change. The collapse of Britain's Roman economy meant Britons lived in a similar society to their Anglo-Saxon neighbors. So, Anglo-Saxons wouldn't need to borrow words for new things. If Old English became the most important language in an area, speakers of other languages might have found it useful to become bilingual. Over a few generations, they might stop speaking the less important languages (British Celtic or Latin). This idea, which only needs a small number of powerful Germanic-speaking migrants, has become the "standard explanation" for why Celtic and spoken Latin died out in post-Roman Britain.

Elite Names and Culture

Many studies agree that a good number of native British people from lower social classes probably survived. They became "Anglicized" (adopted English ways) because of "elite dominance." But there's also evidence that some British leaders survived and became Anglicized. An Anglo-Saxon elite could form in two ways:

- An incoming chief and his war band from northern Germania taking over an area.

- A native British chief and his war band adopting Anglo-Saxon culture and language.

The fact that some "Anglo-Saxon" royal families have British Celtic personal names suggests the second process. The Wessex royal line was traditionally started by Cerdic, a Celtic name similar to Ceretic. This might mean Cerdic was a native Briton, and his family became Anglicized over time. Some of Cerdic's supposed descendants also had Celtic names, like Ceawlin. The last British name in this family was King Caedwalla, who died as late as 689.

This suggests that southern Britain (especially Wessex, Kent, Essex, and parts of East Anglia) was taken over by families with some Germanic roots or connections. But they also had origins in, or married into, native British leading families.

What Does Archaeology Show?

Archaeologists studying the Anglo-Saxon period look at how people identified themselves. They consider gender, age, ethnicity, religion, and social status together. This helps them understand if people migrated or if cultures mixed.

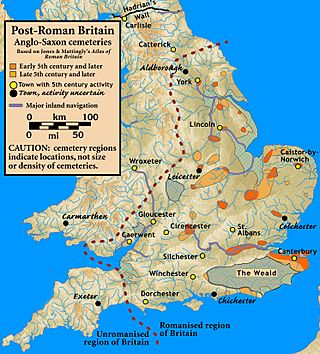

It has been hard to put together all the archaeological findings for the Anglo-Saxon period. But new studies, especially on finds from Spong Hill, have helped. They suggest the settlement started earlier than 450 AD.

Understanding the Roman Past

Archaeological evidence shows that Roman material culture (everyday objects) collapsed in the early 400s. This left a gap that was quickly filled by Anglo-Saxon objects. The native British culture became almost invisible in the archaeological record. However, recent finds show that coin use and imports didn't stop suddenly in 410 AD.

Evidence of Settlers

We see signs of Anglo-Saxons being used as foederati (allied troops) in burials. Some Anglo-Saxons were buried with military gear like that given to late Roman soldiers. These burials are found in Roman cemeteries, like Winchester and Colchester. They are also in 'Anglo-Saxon' rural cemeteries like Mucking (Essex), which was also used by Romano-Britons. The earliest Anglo-Saxon sites are often near Roman settlements and roads. This suggests that early Anglo-Saxon settlements might have been controlled by the Romano-Britons.

However, not all early settlers were necessarily allied troops. There could have been many different relationships between Romano-Britons and Anglo-Saxons. The archaeological evidence suggests that no single explanation fits all Anglo-Saxon settlements. There were big differences from region to region. Some settlers were warriors buried with weapons. But others were humbler people with few weapons, who suffered from poor nutrition. These might have been Germanic 'boat people', refugees from crowded areas in the North Sea region.

Tribal Characteristics

It's easy to think of Anglo-Saxon archaeology only as a study of ethnic groups. But identity was more about belonging to a family or tribe, being Christian or pagan, or being rich or poor. "Anglo-Saxons" or "Britons" were not all the same. In the early Anglo-Saxon period, identity was local. People might have shown their tribal loyalty through their clothing and fasteners. It's important not to think of them with modern ideas of nationalism. They probably didn't think of themselves as "Anglo-Saxon." Instead, they were part of a tribe or region, or followers of a leader.

An excavation at Alwalton near Peterborough found a cemetery with both cremations and burials. These dated from the 400s to the 600s. Both types of burials had grave goods. Some were very rich. The excavation showed a mix of practices and symbolic clothing. These reflected local differences, likely linked to tribal or family loyalty. Clothing was very symbolic, and clear differences could be seen between groups in the cemetery.

The style of brooches (called Quoits), unique to southern England in the 400s, shows that a new "Anglo-Saxon" culture was developing early on. It wasn't just brought over from the continent.

Skeletal evidence can also tell us about mixing populations. The average height of Anglo-Saxon men dropped in the 600s–700s compared to the 400s–500s. This is most clear in Wessex. This drop isn't easily explained by changes in diet or new immigrants. Since Britons were generally shorter, the most likely reason is that native people slowly adopted Saxon culture. They became more assimilated into Anglo-Saxon communities, and there was more intermarriage.

At Stretton-on-Fosse II (Warwickshire), a burial site near two Romano-British cemeteries, 82% of adult males had weapons. This is much higher than average in southern England. The continuity of native women at this site is suggested by textile techniques and shared physical traits. But the skeletal evidence also shows a new type of taller, more slender male appearing after the Roman period. This suggests a group of males, probably Germanic, took control and married native women.

Landscape Archaeology

The Anglo-Saxons did not settle in an empty land and then create new types of farms. By the late 300s, the English countryside was mostly cleared and had scattered farms and small villages. Each had its own fields but often shared other resources. This stable system changed within a few decades of the 400s. Early "Anglo-Saxon" farmers focused on growing enough food to survive. They turned large areas of previously plowed land into pasture. However, there is little evidence that land was simply abandoned.

Evidence across southern and central England increasingly shows that old field layouts from prehistoric and Roman times continued into the Anglo-Saxon period. This was true whether or not these fields were continuously plowed. This suggests that family ties and social relationships continued through the 400s and 500s. There's no evidence of widespread destruction by invaders.

Studies have found examples of old land boundaries continuing. For instance, Roman villa estate boundaries seem to have been the same as medieval estates. This suggests that the basic structure of early Anglo-Saxon local government was inherited from late Roman Britain.

Where Did They Settle?

It's hard to find early Anglo-Saxon settlements because most rural sites have few finds other than pottery and bone. Aerial photos don't easily show them, partly because many settlements were spread out.

Many inland settlements are on rivers that were important travel routes during Roman times. These places, like Dorchester on Thames, were easy to reach by the shallow boats the Anglo-Saxons used. The same is true for settlements along other major rivers. There were also Jutish settlements on the Isle of Wight and the nearby southern coast of Hampshire.

Some Anglo-Saxon settlements are near Roman towns. But it's not clear if Anglo-Saxons and Romano-Britons lived in these towns at the same time. For example, at Roman Caistor-by-Norwich, recent studies suggest the cemetery was used after the town was mostly abandoned.

Cemetery Clues

The earliest cemeteries identified as Anglo-Saxon are found in different regions and date to the early 400s. The exception is Kent, where many cemeteries and objects suggest a very heavy Anglo-Saxon settlement, or continuous settlement from an early date, or both. By the late 400s, there were more Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, some next to older ones. They also appeared along the southern coast of Sussex.

By the year 2000, about 10,000 early 'Anglo-Saxon' cremations and burials had been found. They show a lot of different styles and burial rituals. This fits with the idea of many small cultures and local practices. Cemetery evidence still relies on objects found: clothes, jewelry, weapons, pots, and personal items. But physical and molecular evidence from skeletons, bones, and teeth is becoming more important.

The presence of objects that are clearly North Germanic along the coast between the Humber Estuary and East Anglia shows that Scandinavians migrated to Britain. However, this doesn't mean they arrived at the same time as the Angles. They might have come almost a century later.

The process of mixing and blending immigrant and native populations is very hard to see with just objects. But skeletal evidence can help. The average height of male individuals in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries dropped in the 600s–700s. This is most noticeable in Wessex. This drop is not easily explained by environmental changes. There's no evidence of a change in diet or more immigrants at this time. Since Britons were generally shorter, the most likely explanation is a gradual adoption of Saxon culture by native groups. This means more native people became part of Anglo-Saxon communities and more intermarriage happened.

What Does DNA Tell Us?

Scientists have used different types of DNA evidence to study how much immigration, cultural blending, and intermarriage contributed to the creation of Anglo-Saxon England.

Ancient DNA Studies

A 2022 study looked at DNA from 460 people from England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark, dating from about 200 to 1300 AD. It found that in eastern England, a large number of immigrants, both men and women, arrived after the Roman era. More than half of the early medieval people from central and eastern England got over 75% of their DNA from a population matching early medieval people from northern Netherlands to Denmark. There were clear signs that people with two types of ancestry lived together and mixed. Some individuals had 100% of their DNA from this immigrant source, while others in the same burial grounds had 100% local ancestry, matching Irish, Welsh, and Scottish people more closely.

The study also found a second important source of post-Roman immigration. This group's DNA matched Iron Age French individuals. The authors suggested this might be from medieval migration from Frankish areas. This ancestry was already common in southeastern England in the early Middle Ages. It made up about 51% of the DNA of people studied there. It became more widespread over time, possibly due to continuous migration. Neither of these two post-Roman migrations significantly contributed to the DNA of modern Ireland, Wales, or Scotland. The authors estimate that modern English DNA comes about 41% from northern Europe, 34% from British Iron Age people, and 25% from French Iron Age people. The study also confirmed an increase in Scandinavian DNA during the Viking period.

Another 2020 study, using DNA from Viking-era burials across Europe, found that modern English samples showed about a 38% genetic contribution from a native British "North Atlantic" population. They also found a 37% contribution from a Danish-like population. Researchers estimated that up to 6% of the Danish-like DNA could be from Danish Vikings, with the rest from the Anglo-Saxons.

A 2018 study, focusing on Ireland's genetics, combined ancient DNA data. It found that modern southern, central, and eastern English populations were "predominantly Anglo-Saxon-like." But those from northern and southwestern England had more native origins.

In 2016, a study of burials in Cambridgeshire found evidence of intermarriage in the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlements. The highest status grave belonged to a woman of local, British, origin. Two other women were of Anglo-Saxon origin, and another showed signs of mixed ancestry. People of native, immigrant, and mixed ancestry were buried in the same cemetery. They had grave goods from the same culture, with no clear differences. The authors noted that their results go against earlier theories that said there was strict separation between natives and newcomers.

Modern Population Studies

A big study in 2015 by Leslie et al. looked at the "fine scale genetic structure of the British population." It found regional patterns of genetic differences. These patterns reflected historical population events and sometimes matched the boundaries of old kingdoms. The study found clear evidence in modern England of the Anglo-Saxon migration. It also identified regions that did not carry genetic material from these migrations. The authors suggested that the amount of "Saxon" ancestry in Central/Southern England was probably between 10% and 40%.

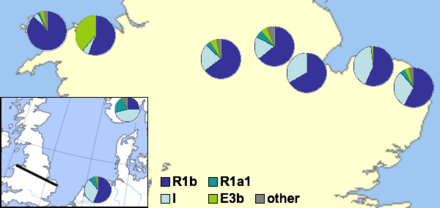

Y-chromosome Evidence

Early studies of British ancestry often looked at Y-chromosome DNA. Males inherit the Y-chromosome directly from their fathers. This allows scientists to study male-only family lines.

One study looked at Y-chromosome differences across England and Wales. It compared them to samples from Friesland (a source of Anglo-Saxon migrants) and Norway (a source of later Viking migrations). It found that in England, in small samples, 50% to 100% of male genetic inheritance came from people from the Germanic coastlands of the North Sea.

Other research in 2003, with a larger sample, suggested that in southernmost England, including Kent, continental (North German and Danish) male genetic input was between 25% and 45%, with an average of 37%. East Anglia, the East Midlands, and Yorkshire all had over 50%. The study couldn't tell the difference between North German and Danish populations. So, it couldn't say how much DNA came from Anglo-Saxon settlements versus later Danish Viking colonization. The average Germanic genetic input in this study was 54%.

A theory called the "apartheid-like social structure" was proposed to explain how a small number of settlers could have contributed a lot to the modern gene pool. This idea has been criticized. It has also been suggested that the genetic similarities across the North Sea might be due to a long process of population movement, possibly starting before the Anglo-Saxons or Vikings.

More recent work has challenged some of these older theories. David Reich's lab found that the Bell Beaker People from the Lower Rhine had little genetic relation to people from Spain or southern Europe. The Beaker Complex in Britain was linked to a replacement of about 90% of Britain’s gene pool within a few hundred years. Modern DNA clustering shows that British and Irish people are genetically very close to other North European populations, not to people from Spain or France. More recent research supports the idea that genetic differences between the English and Welsh come from the Anglo-Saxon settlement, not older migrations.

Criticism of DNA Studies

Some scholars have questioned whether it's right to link ethnic and cultural identity with patterns found in DNA evidence. A 2018 editorial in Nature argued that using this data too simply risks going back to old, problematic ideas in archaeology. For example, it's not clear if "Germanic" peoples truly shared a cultural or ethnic unity beyond speaking similar languages.

How Did Migration and Culture Change Happen?

Experts have used all the evidence to create models that try to answer questions about the Anglo-Saxon settlement. These questions include how many migrants there were, when the Anglo-Saxons became politically powerful, and what happened to the Romano-British people in the areas they took over. The later Anglo-Saxons were a mix of invaders, migrants, and native people who adopted the new culture. The exact numbers and relationships between these groups are still being studied. The traditional idea of the settlement has been re-examined. Scholars now accept evidence for both migration and cultural blending.

Estimating Migrant Numbers

Knowing how many migrants came from the continent helps experts understand the events of the 400s and 500s. Archaeologists often start by estimating the population of Roman Britain in the 200s and 300s, usually between 2 and 4 million. Some experts believe that after political collapses, the population of what would become Anglo-Saxon England fell to 1 million by the 400s.

Within 200 years of their arrival, Anglo-Saxon villages were about 2 to 5 kilometers apart in settled areas. If each village had about 50 people, this means an Anglo-Saxon population of 250,000 in southern and eastern England. The number of migrants then depends on how much the population grew. If it grew by 1% per year, about 30,000 migrants would be needed. If it grew by 2% per year, it would be closer to 5,000 migrants. Finds from Spong Hill show over 2,000 cremations and burials in a very large cemetery. But since it was used for over 200 years, it was likely a major cemetery for a whole area, not just one village. This suggests a smaller number of original immigrants, possibly around 20,000.

One expert concluded that "most of the biological and cultural evidence points to a minority immigration of 10 to 20% of the native population." The immigration itself was not a single 'invasion'. Instead, it was a series of arrivals and movements over a long time. It differed from region to region. The total immigrant population might have been between 100,000 and 200,000 over about a century.

However, there's a difference between some archaeological and historical ideas about the size of Anglo-Saxon immigration and the DNA estimates of their genetic contribution to modern English people. Some studies have shown that a genetic group can grow from less than 5% to more than 50% in just 200 years. This can happen with a slight advantage in having more children and limited intermarriage between groups.

Saxon Political Power in Britain

People are now rethinking the idea of decay and breakdown in post-Roman Britain. Some suggest that sub-Roman Britain kept significant political, economic, and military strength through the 400s and even most of the 500s. This comes from attempts to show British success against the Anglo-Saxons, as suggested by later chronicles. However, recent studies question how historically accurate these chronicles are for the period around 500 AD.

The idea of long-lasting British victories against the Saxons appears in many parts of the Chronicles. But it comes from Gildas's short mention of a British victory at Mons Badonicus (Mount Badon). Some experts suggest the war between Britons and Saxons ended in a compromise. This gave the newcomers a very large area of influence in Britain. Other experts argue for the continuation of British political, cultural, and military power well into the late 500s, even in eastern England.

Cremation cemeteries in eastern Britain north of the Thames begin in the second quarter of the 400s. This is supported by the Gallic Chronicle of 452, which says that large parts of Britain fell under Saxon rule in 441.

What Happened to Romano-Britons in the South-East?

Many ideas have been suggested about why Romano-Britons seem to disappear from the archaeological and historical records of the Anglo-Saxon period.

One idea, first proposed by Edward Augustus Freeman, is that Anglo-Saxons and Britons were competing cultures. Through invasion, extermination, slavery, and forced resettlement, the Anglo-Saxons defeated the Britons. As a result, their culture and language took over. This view has greatly influenced how people understand the process of Anglicization in Britain. It remains the starting point for comparing other ideas. Many scholars still consider widespread extermination and displacement of native peoples a possible explanation. This view is largely supported by language evidence and the few early writings.

Another idea challenges this. It suggests that the Anglo-Saxon migration was an elite takeover, similar to the Norman Conquest. In this view, most of the population was Britons who adopted the culture of the conquerors. One process leading to Anglo-Saxonization is like what happened in Russia or North Africa. A politically and socially powerful minority culture is quickly adopted by a settled majority. This is called 'elite dominance'. Another process is explained by incentives. For example, the wergild (a legal payment for injury or death) in the law code of Ine of Wessex. The wergild of an Englishman was twice that of a Briton of similar wealth. This difference in status might have encouraged Britons to become Anglo-Saxon or at least English-speaking.

While most scholars now accept that some people continued to live in Britain from the Roman period, this view has been criticized. Some argue that the settlement was done by small, farming family groups. The lack of early evidence for a strong elite suggests that such a group didn't play a big role.

Several theories suggest how the number of native Britons could have decreased without violence. There is language and historical evidence for a significant movement of Brittonic-speakers to Armorica, which became known as Brittany. Also, some have guessed that diseases arriving through Roman trade links might have affected Britons more.

Regional Differences in Settlement

In recent years, scholars have tried to combine ideas of mass migration and elite dominance. They emphasize that no single explanation can cover all cultural changes across England. The Anglo-Saxon migration was a process, not a single event. It varied over time and in different places. This led to different immigrant groups, origins, and sizes of settlements.

East Anglia has been identified as a region where a large-scale continental migration happened. This might have followed a period of fewer people in the 300s. Lincolnshire has also been named as a key early settlement center. Some argue that in Essex, the cultural change seen in archaeology is so complete that a large number of people must have migrated. In Kent, archaeological and written evidence supports migrations as the main reason for cultural change.

Immigration into the area that became Wessex came from both the south coast and the Upper Thames valley. The earlier southern settlements might have been simpler than the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle suggests. Powerful Romano-British trading ports might have directed many Germanic settlers inland. In areas settled from the Thames, different things might have happened, with Germanic immigrants having more power.

In the northern kingdom of Bernicia, a small group of immigrants might have replaced the native British elite and taken over the kingdom. A study of place names in northeastern England and southern Scotland found that immigration in this region was focused on river valleys. The Britons moved to less fertile hill country and slowly adopted the new culture over a longer time.

Why Was the Anglo-Saxon Settlement Successful?

The reasons for the success of Anglo-Saxon settlements are still not fully clear. One idea is that in Anglo-Saxon society, "local and extended family groups remained... the essential unit of production." These family groups, along with social advantages, freedom, and connections to leaders, might have allowed Anglo-Saxon culture and language to thrive in the 400s and 500s.

Anglo-Saxon Political System

Some historians believe that the success of the Anglo-Saxon leaders in reaching an early agreement after the Battle of Badon was key. This led to their political power across southern and eastern Britain. This power needed some structure to succeed.

The Bretwalda concept suggests the presence of several early Anglo-Saxon leading families and a clear overall leadership. It's not clear if most of these leaders were early settlers, descendants of settlers, or Roman-British leaders who adopted Anglo-Saxon culture. Most experts believe they were migrants. They were small in number but had enough power to ensure "Anglo-Saxon" culture spread in the lowlands of Britain. These leaders established their power through their family ties.

The Tribal Hidage shows that southern and eastern Britain might have broken into many small, independent areas in the 400s and 500s. But late Roman administrative organization might have helped define their borders. By the end of the 500s, the leaders of these communities were calling themselves kings. Most of the larger kingdoms were on the south or east coasts. These areas were settled first and by the most people. So, they were probably the first to change from Romano-British to Anglo-Saxon control. Once established, they could easily communicate with continental Europe via the North Sea or the Channel.

Bede's Bretwalda list suggests that these leaders could collect tribute and impress or protect communities. These "Anglo-Saxon" families took turns in this role. Their success was felt beyond their own areas, reaching neighboring British lands in central and western England, and even the far west of the island. Bede clearly stated that English power could include both British and English kingships. Britons and Angles even marched to war together in the early 600s, under both British and English kings.

Rural Life and Family Groups

Where farming continued in early Anglo-Saxon England, there seems to have been a lot of continuity with the Roman period. This was true for field layouts and farming methods. The biggest changes in land use between about 400 and 600 AD were in how much land was used for grass or plowing, not in how fields were laid out.

Anglo-Saxons settled in small groups of scattered local communities. These farms often moved. This movement, common across Northern Europe, involved either gradually shifting the settlement within its boundaries or moving it completely. Why farms were abandoned and moved is debated. It might be related to the death of a family leader or the desire for better farmland.

These farms are often wrongly called "peasant farms." However, a ceorl, the lowest-ranking free man in early Anglo-Saxon society, was not a peasant. He was a male who owned weapons, had access to law, was supported by his family, and had a wergild. He was at the top of a large household that worked at least one hide of land. The ceorl is likely linked to the common timber buildings of the early Anglo-Saxon period, grouped with others from the same family. Each such household head had less-free dependents and slaves.

The success of rural life in the 400s and 500s, according to landscape archaeology, was due to three things:

- Continuity: No evidence of big changes in the landscape from the past.

- Freedom: Farmers had freedom and rights over their land. They paid rent or duty to a leader who had little control over their daily lives.

- Shared land: Common outfield land (part of a farming system) helped build family and group cultural ties.

Everyday Objects and Culture

The origins of the timber building style seen in early Anglo-Saxon England have been much debated. Some archaeologists have noted the strong similarity between Anglo-Saxon timber halls and Roman-British rural houses. The Anglo-Saxons did not bring the 'long-house', their traditional dwelling from the continent, to Britain. Instead, they kept a local British building tradition that went back to the late 100s. This has been seen as evidence that family and household structures continued from the Roman into the Anglo-Saxon period.

In the Sutton Hoo burial, perhaps of the East Anglian king Raedwald, a long and complex iron chain was found. It was used for hanging a cauldron. This chain was made using a continuous British metalworking tradition from pre-Roman times. However, this was a high-status object.

For some, the lack of native influence on everyday objects shows the success of Anglo-Saxon culture. From beads and brooches to clothes and houses, something unique was happening in the early Anglo-Saxon period. The evidence from objects shows that people adopted and changed styles based on their roles and traditions. This suggests a society where people relied on others to fulfill roles. What they had around them made a statement, not about the individual, but about "identity between small groups."

Looking beyond simple 'homeland' ideas, some explain the changes within a larger 'North Sea interaction zone.' This zone included lowland England, Northern Gaul, and northern Germany. These areas experienced big social and cultural changes after the Roman collapse. This happened not only in former Roman provinces but also in areas outside Roman control. All three areas saw changes in social structure, settlement patterns, and ways of expressing identities. These changes also created reasons for people to move in many directions.

Beliefs and Religion

Studying pagan religious practices in the early Anglo-Saxon period is hard. Most texts that might have information were written later by Christian writers. These writers often disliked pre-Christian beliefs and might have changed how they described them. Much of what we know about Anglo-Saxon paganism comes from later Scandinavian and Icelandic texts. There's a debate about how relevant these are.

One Anglo-Saxon cultural practice that is better understood is burial customs. This is thanks to archaeological digs at places like Sutton Hoo and Spong Hill. There are about 1,200 furnished cemeteries (with objects in graves). These were once thought to be pagan, but their religious meaning is now debated. There was no single way to bury the dead. Cremation was preferred in the north, and burial in the south. But both were found throughout England, sometimes in the same cemeteries. When cremation happened, ashes were usually put in an urn and buried, sometimes with grave goods.

For burials, the usual direction was west–east, with the head to the west. Grave goods were common. Free Anglo-Saxon men were buried with at least one weapon, often a seax (a type of knife), or a spear, sword, or shield. Sometimes, parts of animals were buried in graves, like goats, sheep, or oxen. It's thought these were food for the dead. In some cases, animal skulls were buried in human graves, a practice also seen in earlier Roman Britain.

Despite earlier confidence, experts now question whether burying objects with the dead in post-Roman Britain necessarily means pagan beliefs or beliefs about an afterlife.

There is also evidence that Christianity continued in south and east Britain. The Christian shrine at St Albans and its worship of a martyr survived. Anglo-Saxon poems, like Beowulf, show some interaction between pagan and Christian practices. While not much is studied on this, there's enough evidence to assume some continuing, perhaps freer, form of Christianity survived.

Anglo-Saxon paganism was not based on faith. It was about rituals meant to bring benefits to individuals and the community. As kingship grew, it probably clashed with the powerful priestly class. Becoming Christian gave kings priests who were under their protection and influence. So, Christianization seems to have been mainly supported by kings.

Language and Stories

We don't know much about the everyday spoken language of people during the migration period. Old English is a contact language. It's hard to figure out the simple language used back then from the written language found in West Saxon literature 400 years later. Two main ideas explain why people changed their language to Old English:

- A person or household changed to serve a powerful leader.

- A person or household changed by choice because it gave them economic or legal advantages.

According to Nick Higham, adopting the language, objects, and traditions of an Anglo-Saxon elite was key. Many local people wanted to improve their status. They went through a strict process of cultural blending. This led to the "myths that tied the entire society to immigration as an explanation of their origins in Britain."

The end of the poem "The Battle of Brunanburh" (a 900s Anglo-Saxon poem) gives a poetic voice to the English idea of their origins:

| Old English | Modern English |

|

...Engle and Seaxe upp becomon, |

...Angles and Saxons came up |

This 'heroic tradition' of conquering newcomers fits with the belief of Bede and later Anglo-Saxon historians. They thought the English came solely from Germanic migrants, not from mixing with native British people. It also explains why poems and heroic stories like Beowulf remained popular. The success of the language is the most obvious result of the settlement period. This language, through its stories and poetry, became the force of change.

See Also

Images for kids

-

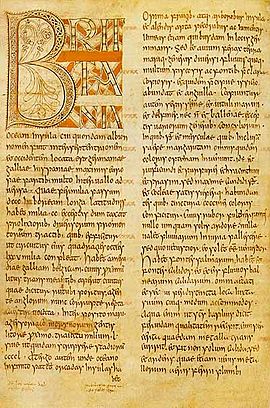

Folio 3v from the Petersburg Bede. The Saint Petersburg Bede (Saint Petersburg, National Library of Russia, lat. Q. v. I. 18), a near-contemporary version of the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

-

Kenneth Jackson's map showing British river names of Celtic etymology, thought to be a good indicator of the spread of Old English. Area I, where Celtic names are rare and confined to large and medium-sized rivers, shows English-language dominance to c. 500–550; Area II to c. 600; Area III, where even many small streams have Brittonic names to c. 700. In Area IV, Brittonic remained the dominant language 'till at least the Norman Conquest' and river names are overwhelmingly Celtic.

-

Map of place-names between the Firth of Forth and the River Tees: in green, names likely containing Brittonic elements; in red and orange, names likely containing the Old English elements -ham and -ingaham respectively. Brittonic names lie mostly to the north of the Lammermuir and Moorfoot Hills.

-

The name of the Bretwalda Ceawlin, rendered 'ceaulin', as it appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (C-text)

-

Romano-British or Anglo-Saxon belt fittings in the Quoit Brooch Style from the Mucking Anglo-Saxon cemetery, early 5th century, using a mainly Roman style for very early Anglo-Saxon clients

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |