Becket controversy facts for kids

The Becket controversy was a big disagreement between Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and King Henry II of England. It lasted from 1163 to 1170. This argument ended sadly with Becket's murder in 1170. Later, Becket was made a saint in 1173. King Henry II also showed his regret publicly in Canterbury in 1174.

The main problem was about who had more power: the king or the Church. King Henry II wanted to bring back some old royal powers. But Archbishop Becket stood against him. A big part of their fight was about who should judge churchmen (called clerics) if they committed crimes. Even those with small roles in the Church were considered clerics.

The argument went on for years. Both sides asked the Pope for help. The Pope tried to get them to agree, but it didn't work. The king took away property, and Becket used excommunication (kicking people out of the Church). These actions made the fight even worse.

Contents

Why the Dispute Started

King Henry II chose his friend, Thomas Becket, to be the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162. The old archbishop had died in 1161. Henry hoped that having his good friend Becket in charge would help him control the English Church better. He wanted the king's power over the Church to be like it was during his grandfather's time, King Henry I of England.

But soon after Becket became archbishop, he changed a lot. He stopped being the king's chancellor (a top government job). He also changed his lifestyle completely. Before, Becket lived a fancy life. Now, he wore a rough shirt (called a cilice) and lived a very simple, strict life. He stopped helping the king's interests in the Church. Instead, he started fighting for the Church's rights.

Key Issues in the Conflict

Many small arguments added to the big problem. But the main issue was about what to do with churchmen who broke the law. Even men who had taken minor church roles were considered clergy. This meant the argument about "criminous clerks" (clergy who committed crimes) could affect about one-fifth of all men in England!

Becket believed that only the Church should judge clergy for any crimes, even if they were against the country's laws. This was called the "benefit of clergy." But King Henry felt this stopped him from ruling properly. He also thought it weakened law and order in England. Henry believed that old English laws supported his view.

Other problems between the king and Becket included:

- Becket trying to get back lands that the archdiocese (the archbishop's area) had lost. He sometimes used royal orders to do this. His strong actions made many people complain to the king.

- Henry's attempt to collect a tax called "sheriff's aid" in 1163. Becket said this tax was a gift, not something people had to pay. This led to a big argument in July 1163.

- Becket excommunicating a powerful nobleman who had stopped the archbishop from putting a churchman into a church. The nobleman said he had the right to choose.

- Another argument where Becket had to agree that no powerful nobleman could be excommunicated without the king's permission.

Leading to Becket's Exile

In October 1163, King Henry called all the church leaders to Westminster. He wanted them to hear his complaints about how the English Church was being run. At first, the bishops supported Becket. The king then asked if they would follow the old customs of England. The bishops still sided with Becket. They refused to follow customs if they went against Church law.

The meeting lasted only one day. The next day, the king took his son, Henry the Young King, away from Becket's care. He also took back all the honors he had given Becket. This showed that Becket was no longer in the king's favor.

Over the next year, both sides tried to get an advantage. They worked to find allies. The king got many bishops to support him. Both sides also sent requests to the Pope. Becket also contacted King Louis VII of France and the Holy Roman Emperor. The Pope, Alexander III, didn't take sides. He told both Henry and Becket to be calm. Becket also started looking for safe places to go in Europe if he needed to leave England.

In January 1164, the king called his powerful nobles and bishops to Clarendon Palace. The king demanded that Becket and the bishops promise to follow the Church customs from his grandfather's time without question. Becket first refused. But after threats, he agreed to support the customs. He then told the other bishops to agree too.

The king then had a group of nobles and clerks write down these customs. This document became known as the Constitutions of Clarendon. Becket asked for time to think about them, but he eventually accepted them. The bishops also swore to uphold these rules.

In August 1164, Becket tried to go to France without permission. This was against the new Constitutions. He was caught. Then, on October 6, 1164, he was put on trial. The charges were about not dealing with a lawsuit properly. This lawsuit was brought by a nobleman named John Marshal about lands Becket had taken.

At the trial, Becket was found guilty of ignoring the court summons. He had to give up all his property (except land) until the king decided what to do. However, the original land dispute was decided in Becket's favor. The king then brought more charges. He asked Becket to explain how he spent money when he was chancellor. Another charge was that he wasn't following the Constitutions. Becket refused to answer these new charges. He was found guilty of both. The archbishop refused to accept the punishment. He then ran away from Northampton and found safety in a church.

Becket's Time in Exile

Thomas Becket sailed to Europe on November 2, 1164. He eventually reached Sens, where both sides presented their arguments to Pope Alexander. The Pope didn't order Becket back to England, as the king wanted. But he also didn't tell the king to back down. Instead, Becket went to live in exile at Pontigny. After this, the king took away all the income of Becket's churchmen who had gone into exile with him. The king also ordered Becket's family and servants to leave England.

While in exile, Becket wrote many letters to English noblemen and bishops. He exchanged letters with Gilbert Foliot, the Bishop of London. Foliot also received letters from the Pope. Becket kept trying to solve the problem. But Pope Alexander told him not to make the king angry before spring 1166. Meanwhile, Henry had given much of the daily running of the English Church to Foliot. Foliot supported the king but also respected the Pope. Neither Foliot nor Henry wanted to settle with Becket quickly.

In late spring 1166, Becket began to threaten the king with Church punishments if he didn't make peace. Henry ignored the first warnings. But Becket's power grew when he was made a special representative of the Pope (a papal legate) to England in May 1166. In June 1166, Becket excommunicated many of Henry's advisors and church servants. He also excommunicated a bishop, Josceline de Bohon, the Bishop of Salisbury.

The king and Foliot reacted by calling a meeting in London in June 1166. This meeting sent letters to both the Pope and Becket, asking them to stop the excommunications. After these letters were sent, Becket's letters arrived for Foliot. These letters told Foliot to announce Becket's decisions publicly. They also said no one could appeal to the Pope against Becket's punishments. Foliot and the bishops then sent more letters to the Pope.

The king also appealed to the Cistercian religious order in 1166. He complained that their monasteries were helping Becket. He threatened to kick the Cistercian order out of his lands. The Cistercians didn't kick Becket out, but they did talk to him. They pointed out that he wouldn't want to cause trouble for their order. Becket then got help from the King of France, who offered him a safe place at Sens.

In December 1166, Pope Alexander wrote to the English bishops. He said he was sending special papal representatives to England to hear the cases. Alexander wrote two letters, one to the king and one to Becket. The letter to the king said the Pope had forbidden Becket from making the dispute worse until the representatives decided. It also said the excommunicated people would be forgiven when the representatives arrived. The letter to Becket said the Pope had asked the king to let Becket return. It advised Becket to avoid hostile actions.

For the next four years, papal representatives were sent to try and end the dispute. But neither Becket nor Henry wanted to settle. The Pope also needed Henry's support. The Pope was in a long fight with the German emperor and needed England's help.

In November 1167, Foliot was called to Normandy, which Henry II ruled. He met with papal representatives and the king. Henry seemed to agree that the representatives could judge his case against Becket and the bishops' case. Henry also offered a compromise on the Constitutions of Clarendon, which the representatives accepted. However, when the representatives met Becket in November, it was clear Becket would not agree to talk with the king. He also wouldn't accept the representatives as judges. Since the representatives couldn't force Becket to agree, the talks ended. The king and bishops continued to appeal to the Pope.

On April 13, 1169, Becket excommunicated Foliot and several royal officials. He did this even though they hadn't been warned. This was also against the Pope's request not to make such decisions until after talks with King Henry. Becket also warned others that they would be excommunicated if they didn't make peace with him. In his excommunication, Becket called Foliot "that wolf in sheep's clothing."

Foliot tried to get help from other bishops to appeal, but they weren't very helpful. Foliot then decided to appeal his excommunication to the Pope in person. He traveled to Normandy in June or July. There, he met the king. But he didn't go all the way to Rome because the Pope was trying again to get a peaceful agreement. In late August and early September, serious but unsuccessful talks happened between the king and the archbishop.

Foliot then went to Rome. But in Milan, he heard that his messenger at the Pope's court had gotten permission for him to be forgiven by the Archbishop of Rouen. Foliot returned to Rouen, where he was forgiven on April 5. He was allowed back in his church role on May 1. The only condition was that Foliot accept a punishment from the Pope.

Foliot's main problem with Becket's excommunication was that he and the others hadn't been warned. This was against normal rules. Becket and his supporters said there were times when you could excommunicate without warning. But Foliot said this wasn't one of those times. Foliot said Becket's way was "to condemn first, judge second." Foliot's example of appealing excommunications to the Pope was important. It helped create a process for appealing excommunications in the 1100s.

The End of the Dispute and Becket's Death

On June 14, 1170, King Henry's son, Henry the Young King, was crowned as a junior King of England. This was done by the Archbishop of York. This was a problem because it was Becket's right as Archbishop of Canterbury to crown English kings.

This crowning made the Pope allow Becket to place an interdict (a Church punishment that stops religious services) on England. The threat of this interdict forced Henry to talk with Becket in July 1170. Becket and the king reached an agreement on July 22, 1170. This allowed the archbishop to return to England, which he did in early December. However, just before he landed in England, he excommunicated the Archbishop of York, Josceline of Salisbury, and Foliot.

One reason for these excommunications might have been that these three churchmen had people with them who would choose new bishops for empty church positions. They were taking these people to the king in Europe. The king wanted to reward some of his royal clerks with these bishop positions. Some of these clerks were Becket's biggest enemies during his exile.

Becket offered to forgive Josceline and Foliot. But he said only the Pope could forgive the Archbishop of York, because he was also an archbishop. The Archbishop of York convinced the other two to appeal to the king, who was in Normandy. When they did, the king was so angry about the excommunications. This led to him saying the famous words: "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?"

This inspired four knights to leave the king's court in Normandy and go to Canterbury. There, on December 29, 1170, they murdered Becket.

What Happened After Becket's Death

For the ten years the dispute lasted, Henry couldn't choose any new bishops in England to replace those who had died. New bishops were finally chosen only in 1173.

In May 1172, Henry made a deal with the Pope, called the Compromise of Avranches. In this deal, the king promised to go on a crusade (a religious war). He also agreed to allow appeals to the Pope in Rome. He also agreed to remove any customs that the Church didn't like. In return, the king got back good relations with the Pope. This was important because he was facing rebellions from his own sons.

After Becket's death, his excommunications were confirmed. The Pope even called the Archbishop of York, Foliot, and Josceline of Salisbury the "Gilbertine trinity." Foliot was forgiven on August 1, 1171, but he couldn't return to his church role yet. He got his role back on May 1, 1172, after proving he wasn't involved in Becket's murder.

The king performed a public act of regret on July 12, 1174, in Canterbury. He publicly admitted his wrongdoings. Then, each bishop present, including Foliot, hit him five times with a rod. After that, each of the 80 monks of Canterbury Cathedral hit the king three times. The king then gave gifts to Becket's shrine and spent a night praying at Becket's tomb.

Becket's Legacy

Not much actually changed from the king's position early in the dispute. Henry could still choose his own bishops. He also kept many of the rights King Henry I had over the Church. However, the Becket controversy was one of many similar arguments between the Pope and kings in the 1100s.

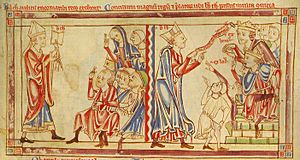

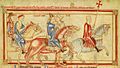

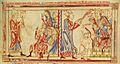

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |