Gilbert Foliot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gilbert Foliot |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of London | |

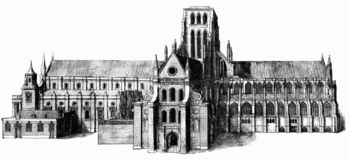

Interior view of Hereford Cathedral. The lower sections predate Foliot's time as bishop.

|

|

| Appointed | 6 March 1163 |

| Reign ended | 18 February 1187 |

| Predecessor | Richard de Beaumis |

| Successor | Richard FitzNeal |

| Other posts | Bishop of Hereford Abbot of Gloucester |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 5 September 1148 by Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1110 |

| Died | 18 February 1187 |

Gilbert Foliot (born around 1110 – died 18 February 1187) was an important English church leader in the Middle Ages. He was a monk, then became the Abbot of Gloucester Abbey. Later, he served as Bishop of Hereford and then Bishop of London.

Gilbert came from a family with many church members. He became a monk at Cluny Abbey in France when he was about 20 years old. After holding two leadership roles there, he became Abbot of Gloucester in 1139. His relative, Miles of Gloucester, helped him get this position. As abbot, Gilbert gained more land for the abbey. He might have even helped create some fake legal documents to win a land dispute.

Gilbert recognized Stephen as the King of England. But he also supported Empress Matilda's claim to the throne. He joined Matilda's side after her forces captured King Stephen. He continued to write letters supporting Matilda even after Stephen was released.

In 1148, Gilbert went with Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury, to a church meeting in France. There, Pope Eugene III appointed him Bishop of Hereford. Gilbert had promised not to support King Stephen. But when he returned to England, he swore loyalty to Stephen anyway. This caused a temporary problem with Henry of Anjou, Matilda's son. Henry later became King Henry II in 1154.

When Archbishop Theobald died in 1160, many people thought Gilbert would become the new Archbishop of Canterbury. But King Henry chose his friend, Thomas Becket, instead. Gilbert later said he was against this choice. He supported King Henry during the king's big argument with Becket. Gilbert was moved to the Diocese of London in 1163. This might have been a way to make up for him not becoming Archbishop of Canterbury.

During the famous argument between Becket and the king, Gilbert was disliked by Becket and his supporters. Gilbert worked as a messenger for the king on many trips related to this argument. He also wrote many letters against Becket that were shared widely. Becket removed Gilbert from the church (called excommunication) two times. The second time happened just before Becket was murdered. After Becket's death, the Pope kept Gilbert excommunicated for a short time. But he was soon allowed back into his church duties.

Besides his role in the Becket argument, Gilbert often served as a royal judge. He was also an active leader and bishop in his different church areas. He wrote many letters, and some were collected after his death. He also wrote sermons and Bible commentaries.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Gilbert Foliot was born around 1110. His father was probably Robert Foliot, who worked for David, the Earl of Huntingdon. Gilbert's mother, Agnes, was the sister of Robert de Chesney, who was the Bishop of Lincoln. Gilbert had other church leaders in his family too. His uncle Reginald was a monk and an abbot. Other relatives were also bishops.

Around 1130, Gilbert became a monk at Cluny Abbey in France. He later became a leader (called a Prior) at Cluny and then at Abbeville. There are signs that he studied law in Italy. He also learned about writing and public speaking. Gilbert also studied the Bible, probably from a teacher named Robert Pullen.

In 1139, Gilbert went to a big church meeting called the Second Council of the Lateran. Pope Innocent II called this meeting. One important topic was Empress Matilda's claim to be the Queen of England. Matilda was the daughter of King Henry I. But after her father died, her cousin Stephen took the crown. By 1139, Matilda had supporters and was fighting Stephen for the throne.

Around 1143, Gilbert wrote a letter about this meeting. The Pope did not decide on Matilda's claim. He told the English Church not to change anything. Gilbert's letter said the meeting discussed if Matilda's parents' marriage was valid. Matilda's mother had been educated in a convent. People wondered if she had taken vows before marrying King Henry I. By 1143, Gilbert believed Matilda was the rightful heir. He supported her claim to the throne.

Becoming an Abbot

In 1139, Gilbert was chosen as the Abbot of Gloucester. The local bishop approved him on June 11, 1139. His relative, Miles of Gloucester, who was then the Earl of Hereford, helped him get this job. Gilbert also had good connections at the royal court. His father had worked for David I of Scotland. David was the uncle of both Empress Matilda and King Stephen's wife. After becoming abbot, Gilbert recognized Stephen as king. But before that, he seemed to support Matilda.

King Stephen was captured by Matilda's forces on February 2, 1141. Matilda called a meeting to gain support for her becoming queen. Gilbert attended this meeting. He was one of her main supporters as Matilda's side tried to put her on the throne.

During his time as abbot, Gilbert wrote a letter defending Matilda's claim. He also wrote that King Stephen had "dishonored the episcopate" (meaning he disrespected the bishops). This was because Stephen arrested some bishops and forced them to give up their castles. Most historians believe Gilbert's letter strongly supported Matilda. However, some historians think his support was not very strong. They point out that his abbey was in an area controlled by Matilda.

As abbot, Gilbert became friends with Aelred of Rievaulx, a writer and later a saint. Aelred even dedicated a book of sermons to Gilbert. Another friend was Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Theobald was trying to unite the English Church. Gilbert helped Theobald by connecting him with Matilda's supporters.

Gilbert also helped his monastery get a smaller church (called a priory) in Hereford. Most of the abbey buildings were built before Gilbert's time. So, we don't know for sure if he added any new buildings. During his time as abbot, a long argument between Gloucester and the Archbishop of York was settled. Gloucester won, partly because of some forged documents. Forging such documents was common in English monasteries back then.

Bishop of Hereford

In early 1148, Gilbert went with Archbishop Theobald to a church meeting in France. King Stephen had forbidden Theobald to go. Gilbert was probably with Theobald when he escaped England in a small fishing boat. The Bishop of Hereford died at this meeting. Pope Eugene III then chose Gilbert to be the new Bishop of Hereford. Theobald had strongly suggested this to the Pope. It seems Gilbert promised not to swear loyalty to Stephen before he became bishop. He was made Bishop of Hereford on September 5, 1148, in France. The other English bishops there refused to help. They said it was against custom for an English bishop to be made bishop outside England. They were also worried that the Pope was ignoring King Stephen's right to have a say. After becoming bishop, Gilbert swore loyalty to Henry of Anjou, Matilda's son.

However, when Gilbert returned to England, he changed his mind. He swore loyalty to King Stephen, which angered Henry of Anjou's supporters. Archbishop Theobald helped make peace. He said Gilbert could not refuse to swear loyalty to "the prince approved by the papacy." Gilbert also tried to keep both his bishop role and his abbot role at the same time. But the monks of Gloucester did not like this. They chose a new abbot instead.

Gilbert supported his uncle, Robert de Chesney, to become Bishop of Lincoln. He wrote to the Pope for his uncle. He also kept in touch with Robert through many letters. Gilbert was also friends with other bishops.

After Henry of Anjou became King Henry II in 1154, Gilbert convinced the Earl of Hereford to give back some royal castles to the king. In 1160, Gilbert wrote to Pope Alexander III. He suggested that King Edward the Confessor should be made a saint. This would be a reward for Henry recognizing Alexander as the true Pope.

Bishop of London

Gilbert Foliot was a rival to Thomas Becket for the Archbishopric of Canterbury. Gilbert thought Becket was too worldly. He was the only bishop or important person known to oppose the king's choice. When Becket was presented to the court, Gilbert said the king had done a miracle. He said the king turned a normal person and a knight into an archbishop. Soon after Becket became archbishop, the king asked the Pope for permission to make Gilbert his royal confessor. This might have been to make Gilbert happy after he didn't get Canterbury. Or, it might have been because the king and Becket were already having disagreements. The king might have wanted Gilbert to balance Becket's influence.

After Becket was chosen as archbishop, Gilbert was nominated to be Bishop of London. He moved there on March 6, 1163. The king had suggested him. He wrote to the Pope that Gilbert would be a better adviser in London. Becket wrote to Gilbert, telling him to accept the move. The Pope confirmed his transfer on March 19, 1163. Gilbert was officially made Bishop of London on April 28, 1163. The Pope's approval was needed because moving bishops was still unusual then. Gilbert did not promise to obey Becket. He said he had already sworn an oath to Canterbury when he became Bishop of Hereford. So, no new oath was needed. This issue was sent to the Pope, but he did not give a clear answer. Gilbert then tried to make London independent from Canterbury. He wanted London to be an archbishopric like Canterbury.

King Henry's Conflict with Becket

King Henry and Becket started arguing in July 1163. At first, it was about money. Then, it was about the king's younger brother marrying an heiress, which Becket stopped. The main reason for the argument was about church members who committed crimes. The king wanted them tried in regular courts. Becket said all church members must be tried in church courts.

At a meeting called by Henry in October 1163, Gilbert first sided with the other bishops. They supported Becket. But after the meeting, Gilbert became the leader of the bishops who supported the king. In January 1164, the king called another meeting. The bishops were asked to approve the Constitutions of Clarendon. These rules would limit the Church's power and the Pope's power in England. Becket refused to approve them. This led to the big argument between the king and Becket.

When Becket appeared before the court, he carried his archbishop's cross in front of him. This was a clear insult to the king. Gilbert told Becket, "If the king were to brandish his sword, as you now brandish yours, what hope can there be of peace between you?" The king refused to see Becket. Becket told the bishops not to judge him. He also threatened to appeal to the Pope. Both of these actions broke the new rules. Gilbert was asked to persuade Becket to change his behavior. Gilbert replied that Becket "was always a fool and always will be."

Becket left the meeting without the king's permission. Soon after, Gilbert tried to suggest a compromise, but Becket refused. Becket then went into exile in France in November 1164. Gilbert was sent with other important people to France and to the Pope. Their job was to stop Becket from getting help. They did not succeed in France, but they had more success with the Pope. The Pope did not side with the king, but he also did not side with Becket.

Becket's Exile and Excommunication

During Becket's exile, Gilbert collected money for the Pope from England. Gilbert believed the argument was not about religion, but about how the church was run. The king took away Becket's lands and the income of church members who followed Becket into exile. Gilbert was put in charge of these incomes in Becket's area. Becket blamed Gilbert for this. But it seems the king made the decision. Gilbert was a careful manager and made sure little money went to the king. Most of it went to religious uses.

In 1165, Pope Alexander III wrote to Gilbert twice. He told Gilbert to tell the king to stop forbidding appeals to the Pope. Gilbert replied that the king respected the Pope. He said Becket was not forced out, but left on his own. Gilbert wrote that the king said Becket could return anytime. But he would still have to answer for his actions. Gilbert advised the Pope not to excommunicate anyone and to be patient. In 1166, Gilbert accused Becket of buying church offices. By 1166, the king had made Gilbert the leader of the English Church, even if not officially. The king and Gilbert got along well. Gilbert's influence probably stopped the king from taking harsher actions against Becket.

On June 10, 1166, Becket excommunicated some of his opponents, including Gilbert. Becket did this even though they had not been warned. The Pope had also asked Becket not to do this. The king responded by ordering the English bishops to appeal to the Pope. Gilbert organized and led this appeal in London on June 24. Gilbert wrote the appeal and a separate letter to Becket. The bishops said those excommunicated had not been warned or allowed to defend themselves. Becket replied to Gilbert with a letter full of anger. Gilbert's reply, called Multiplicem nobis, explained why Becket was wrong. He suggested Becket compromise and be humble. By the end of 1166, Gilbert was able to stop managing the confiscated church incomes. This removed one source of conflict with Becket.

In November 1167, Gilbert met with the king and Pope's representatives in France. The king seemed to agree that the Pope's representatives could judge the case. But when they met with Becket, he refused to accept them as judges. So, the talks ended. The king and bishops continued to appeal to the Pope.

On April 13, 1169, Becket excommunicated Gilbert again. He also excommunicated others, including some royal officials. Becket did this without warning them. The Pope had asked Becket not to do this until talks with the king were over. Becket called Gilbert "that wolf in sheep's clothing." Gilbert tried to get help from other bishops, but they were not very helpful. Gilbert then went to Rome to appeal his excommunication in person. But he heard that he could be absolved by the Archbishop of Rouen. So, Gilbert returned to France. He was absolved on April 5 and allowed back into his church duties on May 1. He only had to accept a punishment from the Pope. Gilbert's main objection was that Becket had excommunicated them without warning. Becket's supporters said it was sometimes allowed without warning. But Gilbert said Becket's habit was "to condemn first, judge second." Gilbert's appeal helped create a process for appealing excommunications in the 12th century.

Becket's Death and Aftermath

On June 14, 1170, King Henry's son, Henry the Young King, was crowned King of England. The Archbishop of York crowned him. This was against the right of Becket, as Archbishop of Canterbury, to crown English kings. It seems likely that Gilbert helped with this coronation. This act made the Pope allow Becket to forbid church services in England as punishment. The threat of this punishment forced Henry to talk with Becket in July 1170.

Becket and the king agreed on terms on July 22, 1170. This allowed Becket to return to England in early December. However, just before he landed, he excommunicated the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of Salisbury, and Gilbert. One reason for this was that these three church leaders were taking people chosen for vacant bishop roles to the king. The king wanted to reward some of his officials with these roles. Some of these officials were Becket's worst enemies. Becket offered to absolve the other two, but said only the Pope could absolve the Archbishop of York.

The three excommunicated church leaders appealed to the king. The king was so angry about these excommunications that he famously asked, "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?" This led four knights to go from the king's court to Canterbury. On December 29, 1170, they murdered Becket.

After Becket's death, his excommunications were confirmed. The Pope referred to the Archbishop of York, Gilbert, and the Bishop of Salisbury as the "Gilbertine trinity." Gilbert was absolved from excommunication on August 1, 1171. But he was still suspended from his duties. He was allowed back into his role on May 1, 1172. He had to prove he was not involved in Becket's murder. The king performed a public act of penance on July 12, 1174, at Canterbury. He confessed his sins. Then, each bishop present, including Gilbert, hit him five times with a rod. The 80 monks of Canterbury Cathedral then hit the king three times each. The king then gave gifts to Becket's shrine and stayed at Becket's tomb.

Gilbert and Becket seemed to be friends until 1163. But their relationship became bad after that. Becket accused Gilbert in 1167 of trying to bring down the Church and him. After the Pope absolved Gilbert in 1170, Becket said, "Satan is unloosed for the destruction of the Church." Some historians believe Becket changed his behavior after becoming archbishop. He wanted to prove he was a better bishop than others. This was to stop Gilbert from making fun of his weaknesses.

Gilbert was mostly a voice for calm in the argument between the king and Becket. He urged Becket to be more controlled. He also stopped the king from enforcing the new rules too strictly. Gilbert's arguments against Becket were sharp and effective. Gilbert also created a new legal way to appeal to the Pope against any future action by the archbishop. Even though his opponents made fun of this, the Pope did not challenge it.

As a bishop, Gilbert served for many years as a judge for the Pope. He was active in supporting his cathedrals and other religious houses. He stayed in close contact with his church officials about running the church areas. He also had clerks who put together a collection of church laws.

Gilbert's Writings

Gilbert Foliot was well known for writing letters. His letters were later collected into a book. About 250 to 300 of his letters still exist. Along with his other legal documents, this makes almost 500 items. These letters cover most of Gilbert's public life. They are a very important source for learning about that time. One historian said that his letters are very valuable because they have so much personal and local detail. Gilbert's letters show him as an active bishop and church leader. He supported church reforms but did not get involved in politics outside the church. His letters are typical of educated writers of his time, very refined and artistic.

Gilbert also wrote sermons and commentaries on the Bible. Only his commentaries on the Song of Songs and the Lord's Prayer still exist. He also wrote nine sermons about Saints Peter and Paul. These sermons were dedicated to Aelred of Rievaulx. Another group of sermons, dedicated to an abbot named Haimo, has been lost.

Death and Legacy

Gilbert Foliot died on February 18, 1187. A writer from that time, Walter Map, praised him. He said Gilbert was "a man most accomplished in the three languages, Latin, French and English, and eloquent and clear in each of them." A modern historian says that Gilbert was so sure he was right that his actions sometimes seemed tricky. He went blind sometime in the 1180s. But he continued to work on his Bible writings.

Gilbert sent his nephew, Richard Foliot, and another clerk to Italy to study law in the 1160s. This shows how important Roman law was becoming. Another nephew, Ralph Foliot, became a royal judge. Gilbert helped his relatives get important positions. All the archdeacons he appointed in London were either nephews or other relatives. A scholar named Roger of Hereford dedicated his book on calculating dates to Gilbert.

Images for kids

-

Interior view of Hereford Cathedral. The lower sections predate Foliot's time as bishop.

-

Medieval seal of Arbroath Abbey depicting the death of Becket

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |