English Benedictine Reform facts for kids

The English Benedictine Reform was a big religious and learning movement in England during the late 900s. At this time, many monasteries were run by priests who were often married. The reformers wanted to change this. They wanted to replace these priests with monks who lived a quiet life, prayed a lot, and followed strict rules set by Saint Benedict.

This movement was inspired by similar changes happening in Europe. The main leaders in England were Dunstan, who became the Archbishop of Canterbury, Æthelwold, the Bishop of Winchester, and Oswald, the Archbishop of York.

In earlier times (the 600s and 700s), most monasteries in England followed Benedictine rules. But by the 800s, learning and monastic life had become much weaker. Alfred the Great (king from 871–899) tried to fix this. Later, King Æthelstan (924–939), the first king of all England, had a court where people from many places gathered. Future reformers like Dunstan and Æthelwold learned a lot from European monks there.

The reform really took off under King Edgar the Peaceful (959–975). He strongly supported removing married priests from monasteries and cathedrals. He wanted to replace them with monks. The reformers worked closely with the king, helping his goals and relying on his support. This movement mostly happened in southern England and the Midlands. The king wasn't strong enough in northern England to take land from local leaders to build new monasteries. The movement slowed down after its main leaders died around the end of the 900s.

The workshops started by Æthelwold created amazing art. This included beautiful manuscript illustrations, sculptures, and gold and silver items. Their art influenced both England and other parts of Europe. In Æthelwold's monasteries, learning was very important. They produced excellent writing and poetry in a fancy Latin style popular back then. His school in Winchester helped create the standard English writing style of the time. His student, Ælfric, became a very famous writer.

All the old stories about this reform were written by people who supported it. They often said bad things about the priests who weren't monks. But today, historians think these stories might be unfair and biased against those priests.

Contents

What Was Happening Before?

The main set of rules for monks in Europe during the early Middle Ages was called the Rule of Saint Benedict. It was written by Benedict of Nursia (around 480–550). Under these rules, monks spent their lives praying, reading holy books, and doing manual work. They lived together and had to obey their abbot (the head of the monastery). Benedict's rules created a stable system that was balanced and sensible.

In the 600s, many monasteries grew in England, strongly influenced by Saint Benedict's ideas. But by 800, few monasteries had high spiritual or intellectual standards. The 800s saw a big decline in learning and monastic life. Problems like Viking attacks and money issues led people to prefer priests who served local communities over monks who lived apart. Land was also increasingly taken from churches by the king.

In the late 800s, King Alfred the Great began to bring back learning and monasticism. His grandson, King Æthelstan (924–939), continued this work. Kings before Edgar the Peaceful (959–975) didn't believe that only Benedictine monasticism was the right way to live a religious life. Sometimes, the difference between regular priests and monks was blurry. Some groups of monks helped local communities, and some priests in churches lived by monastic rules.

How the Reform Started

The Benedictine reform movement in Europe began with the founding of Cluny Abbey in Burgundy around 909–10. England had closer ties with Fleury Abbey in France, which was very respected because it was believed to hold Saint Benedict's body. The English leaders were also influenced by reforms made by the Holy Roman Emperor, Louis the Pious, in the 810s. These reforms aimed to make monastic rules the same everywhere, under the king's power.

England's connections with Europe grew stronger during King Æthelstan's reign. Many books were brought to England, which influenced English art and learning. English church leaders learned about the Benedictine reform happening in Europe.

The main leaders of the English Benedictine reform were Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury (959–988), Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester (963–984), and Oswald, Archbishop of York (971–992). Dunstan and Æthelwold grew up in Æthelstan's court in the 930s. There, they met monks from reformed European monasteries, which inspired them.

In the early 940s, Dunstan became the head of Glastonbury Abbey. Æthelwold joined him, and they spent many years studying Benedictine texts. Glastonbury became the first place to spread monastic reform in England. The Rule of Saint Benedict was translated into Old English around this time, probably by Æthelwold. It's the only surviving translation of the Rule into a European language from that early period.

Around 954, Æthelwold wanted to go to Europe to see the reforms firsthand. But King Eadred (946–955) didn't let him. Instead, he made Æthelwold the head of Abingdon Abbey, which became another important center for reform. Dunstan was sent away by King Eadwig (955–959) between 956 and 958. He spent this time learning about Benedictine practices at St. Peter's Abbey, Ghent in Belgium. Æthelwold, however, seemed to get along well with King Eadwig. This shows that the reformers didn't always agree on everything. Oswald, another leader, was the nephew of Archbishop Oda of Canterbury. Oda supported reform and sent Oswald to Fleury Abbey, where he became a priest and spent much of the 950s.

Kings and the Reform Movement

Monastic reform was a common goal across Europe. Rulers supported it because they believed well-run monasteries would increase their power and fame. In England, the monasteries depended heavily on the royal family, and the Pope had little influence.

When Edgar became king in 959, he strongly supported the reform. He immediately removed the old Archbishop of Canterbury and put Dunstan in his place. In 963, Edgar made Æthelwold Bishop of Winchester. With the king's and the Pope's permission, Æthelwold removed the priests from Winchester's main churches and replaced them with monks. These priests and their supporters were powerful local people. The king had to use force to take their rich church positions.

By 975, about 30 monasteries for men and 7 or 8 for women had been reformed. All of these were in southern England or the Midlands. However, these reformed monasteries were still only about 10% of all religious places. The richest reformed monasteries were much wealthier than regular churches. Some were as rich as the most powerful nobles. But some rich, unreformed churches, like Bury St Edmunds Abbey, continued to do well. The reformers claimed that the church changed completely during Edgar's reign. But some historians think the religious culture was less exclusive than they made it seem.

King Edgar wanted all monasteries in his kingdom to follow the same rules. These rules were written down in a very important document called the Regularis Concordia. It was adopted around 970. Æthelwold wrote the Concordia, getting advice from monasteries in Ghent and Fleury. A main goal was to make church services the same everywhere. Æthelwold tried to combine the best practices from Europe and England.

The Concordia stated that King Edgar wanted everyone to agree on how monasteries should be run. This was to avoid arguments and make sure everyone followed the same rules. The rules from Fleury Abbey had the biggest influence on the Regularis Concordia.

England had recently been united under one king for the first time. Kings like Æthelstan and Edgar saw themselves as heirs to the powerful Carolingian emperors in Europe. Making all monasteries follow the same Benedictine rules helped unite the kingdom and boost the king's power. Monks depended on the king, so their loyalty could be trusted. They could also balance the power of strong local families. The Regularis Concordia required monks to pray for the king and queen several times a day. It also said that the king's permission was needed to choose new abbots.

The reformers wanted to make kingship more Christian. Part of this was raising the status of the queen. Edgar's last wife, Ælfthryth, was the first queen to regularly sign important documents as regina (queen).

The reformers claimed that England was united because Benedictine monasticism was widely accepted. They said King Edgar, their biggest supporter, played a huge role in this by making everyone follow the Benedictine Rule. Æthelwold probably taught Edgar when he was a boy and was very close to him. It's likely Æthelwold convinced the king to support Benedictine monasteries. During Edgar's reign, monks became very powerful in the church leadership.

Æthelwold was also close to Queen Ælfthryth. He supported her son Æthelred (who became king from 978–1016) to be king, against his older half-brother, Edward. Dunstan supported Edward, who became king after Edgar died in 975. Æthelred became king after Edward was murdered in 978. Æthelwold became a powerful figure in the royal court until he died in 984.

Nobles and the Reform

Rich nobles gave gifts to reformed monasteries for religious reasons. Many believed that by supporting holy men who would pray for them, they could save their souls and make up for their sins. Sometimes, gifts were a payment for the right to be buried at a monastery. Some nobles even started new monasteries. For example, Æthelwine, a powerful lord from East Anglia, founded Ramsey Abbey in 969. He gave it many gifts and moved the bodies of two martyred princes there.

Gifts were meant to increase the fame of both the giver and the receiver. For instance, Byrhtnoth, a lord from Essex, gave Ely Abbey valuable gold, silver, crosses, and fine cloths. A local history book says he gave the abbey fourteen estates. After he died, his wife gave the abbey a large tapestry showing his victories and a gold necklace.

Nobles chose which monasteries to support based on their relationships with monks and other nobles. A noble would support the same monasteries that their family members and friends supported. But they might take land from monasteries linked to their political enemies. For example, Æthelwine of East Anglia and Ælfhere, a lord from Mercia, were leaders of rival groups. Ælfhere took land from Æthelwine's Ramsey Abbey. He was an enemy of Archbishop Oswald but a friend of Bishop Æthelwold. Æthelwine, a friend of Oswald, sometimes took land from Æthelwold's Ely Abbey. Oswald himself used his position to help his relatives, leasing church lands to them, even though this was forbidden. Historians note that even religion couldn't break the strong family ties that were the basic social structure in 10th-century England.

The three main leaders of the reform were all from noble families. This helped them get support from their families, friends, and the king. Many historians believe that this close link between monks and nobles was the most important reason for the reform's success. Nobles didn't just support reformed monasteries; they also continued to give gifts to unreformed ones.

Monks and Priests

Nicholas Brooks described Dunstan as "the most capable and best-loved person that 10th-century England produced." He said Dunstan's example helped move a lot of land from nobles to religious groups. This led to a revival of learning, religion, and culture in late 10th-century England, giving the English church a distinct monastic character. However, Brooks also admits it's hard to point to exactly what Dunstan did for the reform after he became Archbishop of Canterbury. Some historians even question how important Dunstan really was as the starter of the reform movement.

Æthelwold reformed monasteries in his own area of Winchester. He also helped restore churches in eastern England, like Peterborough, Ely, and Thorney. Almost all of these had been monasteries in the 600s but later became communities of priests or were owned by nobles. So, Æthelwold could argue he was just bringing them back to their original state. He also restored nunneries, working with his ally, Queen Ælfthryth. He didn't just try to bring back old church practices; he also tried to improve them, sometimes by making up questionable histories for his churches. He was the main promoter of the movement and wrote all the important works supporting it during Edgar's reign.

The main goal of the reform, both in England and Europe, was to set and spread high standards for church services, spiritual life, and helping people. Even though the English reform was inspired by Europe, it wasn't just a copy. It combined European monasticism with ideas for creating a "Holy Society" in England.

In Europe, cathedrals were run by regular priests, and only monasteries had monks. Æthelwold disagreed with this. He removed priests from Winchester Cathedral and replaced them with monks. This was a unique feature of the English reform. Dunstan and Oswald were hesitant to do the same. They had lived abroad and understood European practices. They also preferred a slower approach compared to Æthelwold's more forceful methods. Oswald did put monks in Worcester Cathedral, but he built a new church for them and kept the priests, who were educated with the monks. Canterbury didn't become fully monastic until after Dunstan died.

Æthelwold was a historian who wanted to bring back what he believed were old practices. For example, he looked to Pope Gregory the Great's instructions to Augustine, which said Augustine should continue to live like a monk even as a bishop. Although Saint Benedict's Rule said monks shouldn't do outside work, English Benedictines actively helped people and taught priests. The reformers agreed that priests should not be married. They also thought that individual priests owning property was wrong and wanted all property to be owned by the community.

The first writer about Dunstan was a priest who worked with him at Glastonbury. This writer later left England. After 980, he tried to get support from important English church leaders, but he failed. This was probably because the monastic reformers didn't want to help a priest living abroad. The priests who weren't monks didn't have good writers to defend themselves. So, no writings defending them against Æthelwold's accusations have survived. Later historians, like John of Worcester and William of Malmesbury, were Benedictine monks. They continued to present a negative image of the secular priests. This meant that the diverse churches and religious practices of Anglo-Saxon England were often hidden by a small group who controlled what was written down.

Saints and Holy Objects

Reformers thought it was very important to move saints' bodies and holy objects (relics). They moved them from their original burial places to higher, more visible spots. This made them easier for people to honor. An important early example was moving Saint Benedict's own body from Monte Cassino to Fleury Abbey in the 600s. By the 900s, moving a saint's body usually involved a big parade, a fancy new shrine, and often rebuilding the church.

Almost nothing is known about Swithun, who was an unknown bishop of Winchester in the 800s. But Æthelwold started a major movement to honor him as a saint. He moved Swithun's grave from outside the church to a new shrine inside. After Æthelwold died in 984, he also became a saint. His grave was supposedly neglected until he appeared in a vision and said his body should be moved. His successor, Ælfheah, then built a new part of the church to hold his body, where miracles were said to happen.

People believed saints had power even after death. The reformers worked hard to move saints' bodies and relics from less important churches to their own new monasteries. Æthelwold was very energetic in this. Gifts of land and other items to a church were often given to its main saint. So, taking a saint's remains from an unreformed community could then justify taking its wealth to a Benedictine monastery. The idea was that since the property was given to the saint, it should follow the saint's body to its new home. The reformers were very keen on creating new saints and collecting relics. Stealing relics from unreformed communities to increase a church's collection was common. For example, Ely Abbey "raided" Dereham in 974 to get the remains of Saint Wihtburh. This was probably linked to Ely taking over Dereham church and may have been a way to make sure the abbey kept the church's lands.

However, Oswald, another reform leader, promoted saint cults but didn't seem to use relic collecting to gain control of churches' assets. Dunstan also showed no interest in relics.

Art and Learning

Historians note that even though the reformed monasteries were only in the south and Midlands, they brought a "new golden age" of monastic life and a rebirth of culture, literature, and art to England. Æthelwold's school in Winchester was highly praised by its students. He set high standards for learning. He sent monks to Fleury and Corbie Abbeys to learn about church music. Surviving books of church music from Winchester include works by both European and English composers.

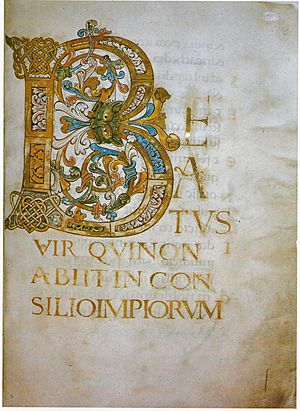

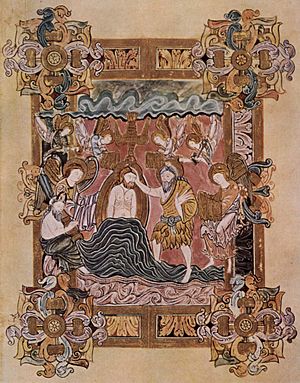

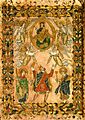

Visual art combined new ideas from European monastic styles with older English features. This style is often called the "Winchester style" or "school," even though other places were involved. Even when new monasteries weren't being built as much in the early 1000s, art continued to thrive as existing monasteries became richer. The Benedictional of St. Æthelwold (a book of blessings from the 970s) is considered the most important of the surviving illuminated manuscripts. It's filled with lavish illustrations and fancy leaf borders. The poem in the book says Æthelwold "commanded... many frames well adorned and filled with various figures decorated with numerous beautiful colours and with gold," and he got what he asked for. It's seen as an "outstanding work of art" from that time. The art workshops started by Æthelwold continued to be influential after his death, both in England and in Europe.

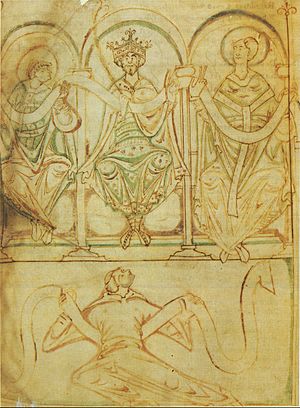

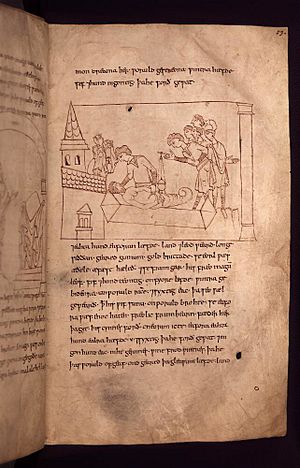

Besides fancy illuminated manuscripts, this period also saw the development of a unique English tradition of line drawing in books. Sometimes, light colors were added. This style developed from European styles. One style was influenced by the Utrecht Psalter, a book of psalms from Europe that arrived in Canterbury around 1000. Each psalm in it has a detailed ink drawing. The Harley Psalter from Canterbury (around the 1020s) is a copy of this, with added colored washes. Dunstan himself was an artist, as were many monks who became important leaders. The earliest known outline drawing is probably by him. It shows him kneeling before Christ. This was added to an older book, likely before he was sent away in 956. The other "Winchester" drawing style is known for detailed and active clothing, which sometimes looks a bit overdone but makes the figures lively. The skilled use of line drawing continued in English art for centuries.

Very few remains of monastic buildings from this time exist. What we know comes from short mentions in documents. St Laurence's Church, Bradford-on-Avon seems to be a rare, nearly complete monastic church from this period. The angels carved in relief were probably part of a large cross display. Generally, old writings give more details about the valuable treasures in precious metal, rich embroidered cloth, and other materials that monasteries collected, mostly from gifts by nobles. The few pieces that survived mostly did so outside England. These include the silver Brussels Cross and an ivory figure from a Crucifixion scene.

The Benedictine reform was a major event in the development of the Old English language. It led to the creation of a standard Old English "literary language." In the late 800s, King Alfred had started a program to translate Latin texts into English. Almost a century later, the monastic reformers revived this idea of producing texts in English for teaching. Æthelwold's school in Winchester aimed to create a standard West Saxon literary language, a plan probably started by Æthelwold himself. His most famous student, Ælfric (around 950–1010), who became the head of Eynsham Abbey, aimed to write using a consistent grammar and vocabulary.

Ælfric, described as the "highest peak of Benedictine reform and Anglo-Saxon literature," shared the movement's ideals of monastic life and love for learning. He also had close ties with important nobles. His works included two series of forty sermons, lives of saints, a Latin grammar in English, and a discussion of different jobs. He advised the king and was an expert on church practices and laws. Later, in the 1500s, his writings were even used to support Protestant ideas.

The reformers were mainly interested in prose (regular writing) rather than poetry. However, most Old English poetry that survives today is found in manuscripts from the late 900s and early 1000s. These include the famous Beowulf manuscript. Even though most of this poetry was probably written much earlier, it survived because the Benedictines were interested in English works. Most surviving English literature from this period was produced by followers of the Benedictine reformers and written in the standard Old English they promoted.

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, the new church leaders from Europe often criticized the state of the Anglo-Saxon church to justify the conquest. They weren't interested in the saints honored by the Anglo-Saxons. However, Anglo-Norman monks soon started using Anglo-Saxon saint stories for their own purposes, and Anglo-Saxon saints regained respect. Monasteries defended their land and privileges by using old Anglo-Saxon documents, even making up fake ones if needed. Later historians saw a pattern of decline in the church, followed by a revival in the 900s, and then another decline before the Conquest. This idea made both the Normans and Anglo-Saxons happy, but some historians think it unfairly downplays the achievements of the periods called "decline."

Why Was This Reform Important?

Historian Simon Keynes says the Benedictine reform was the most important part of King Edgar's reign.

Some historians, like Antonia Gransden, believe there was a continuous tradition of monasticism in England from the 600s. They argue that historians have exaggerated how important the 10th-century reform was and how much it owed to European models. Anglo-Saxons generally respected the past, and monks in the later Anglo-Saxon period saw the time of Bede (in the 700s) as laying the groundwork for their own practices. Some historians even say that the evidence for a single, unified reform movement is "very fragile."

Martin Ryan is also doubtful. He points out that there's little evidence of reform activity in northern England, even though Oswald was Archbishop of York. This might be because the reformers needed royal support to remove priests, and the king's power was too weak in the north to allow this. The most northern Benedictine monastery was Burton upon Trent. Ryan comments that while the Benedictine reforms dominate the historical sources, their wider impact shouldn't be overstated. Large parts of England were barely affected. He believes the growth of small local churches and new ways of caring for people had a more lasting impact on religious life in England.

Julia Barrow agrees, arguing that the establishment of Benedictine monasteries was "not necessarily the most important development" in the English church at the time. The growth in local parish churches was much more significant in terms of numbers.

However, Catherine Cubitt believes the reform "has rightly been regarded as one of the most significant episodes in Anglo-Saxon history." She says it "transformed English religious life, brought back artistic and intellectual activities, and created a new relationship between the church and the king." The wealth of later Anglo-Saxon England was important for its success. This wealth came from trade and diplomacy with Europe, as well as religious needs.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |