Thomas of Bayeux facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thomas |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of York | |

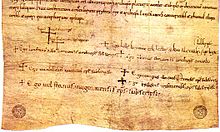

The Accord of Winchester, 1072. Thomas' signature is on the right, next to Lanfranc's.

|

|

| Church | Roman Catholic |

| Appointed | 23 May 1070 |

| Reign ended | 18 November 1100 |

| Predecessor | Ealdred |

| Successor | Gerard |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | probably 25 December 1070 by Lanfranc |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 18 November 1100 York |

| Buried | York Minster |

| Parents | Osbert Muriel |

Thomas of Bayeux (who died on 18 November 1100) was an important leader in the church. He served as the Archbishop of York from 1070 until 1100. Thomas studied in Liège and later became a trusted advisor to Duke William of Normandy. This Duke William later became King William I of England, also known as William the Conqueror.

After William conquered England, he chose Thomas to become the new Archbishop of York. But there was a big disagreement! Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, wanted Thomas to promise that he would always obey him and future Archbishops of Canterbury. Lanfranc believed Canterbury was the most important church leader in England. Thomas said no, arguing that no Archbishop of York had ever made such a promise before. Because of this, Lanfranc refused to make Thomas an archbishop. King William eventually convinced Thomas to agree, but the two archbishops kept disagreeing about who was in charge and which church areas belonged to York.

After King William I died, Thomas served his son, King William II. Thomas even helped the King stop a rebellion led by his old teacher, Odo of Bayeux. Thomas also attended a trial for a rebellious bishop, William de St-Calais, who was the only bishop under York's authority. Later, Thomas again argued with Canterbury when he refused to make Anselm the new Archbishop of Canterbury, unless Anselm was called "Metropolitan" instead of "Primate of England." When King William II suddenly died in 1100, Thomas arrived too late to crown the new King Henry I. Thomas died shortly after this event.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas is sometimes called Thomas I to tell him apart from his nephew, Thomas II of York, who also became Archbishop of York. Thomas's father was a priest named Osbert, and his mother was Muriel. We don't know much else about them. Thomas had a brother named Samson, who was the Bishop of Worcester from 1086 to 1112. Thomas and his family were from Normandy, a region in France.

With help from Odo of Bayeux, who was a bishop, both Thomas and his brother Samson went to Liège for their education. Some historians think Thomas might have also studied with Lanfranc in Normandy. Lanfranc was a famous teacher at the Bec Abbey. Thomas then returned to Normandy and became an official and secretary for Bishop Odo. He was also a church leader and treasurer at Bayeux Cathedral. Before the Norman Conquest, he was part of Duke William's church staff. After the Battle of Hastings, the new King William made him a royal clerk, which meant he helped the King with official papers.

Archbishop Under King William I

Thomas became Archbishop of York in 1070, taking over from Ealdred. He was chosen on May 23 and likely became archbishop on December 25. The King's choice of Thomas was a bit different. Usually, King William would choose Norman nobles or monks for important church jobs. But Thomas was a royal clerk, which was more like how English kings chose bishops before the Conquest.

Soon after Thomas was chosen, Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, demanded that Thomas promise to obey him and all future Archbishops of Canterbury. Lanfranc believed Canterbury was the most important church in England. Thomas refused to make this written promise. He argued that no Archbishop of York had ever been asked to do this before. King William wanted clear rules in the church, just like in his government. So, the King supported Lanfranc in this argument.

The King's pressure made Thomas agree to obey Lanfranc. Thomas was then made archbishop. But his promise was spoken only to Lanfranc, not written down, and it didn't include future Archbishops of Canterbury. This settled the immediate problem between Thomas and Lanfranc. However, it started a very long disagreement, known as the Canterbury–York dispute, about whether Canterbury had authority over York.

The next year, both archbishops went to Rome to get their palliums, which are special church vestments. While there, Thomas asked Pope Alexander II to declare that Canterbury and York were equal. Thomas also wanted the Pope to say that certain church areas in the middle of England, like Worcester and Lichfield, belonged to York, not Canterbury. These areas were south of the River Humber. A writer from Canterbury, Eadmer, later wrote that Thomas gave up his archbishop symbols, but Lanfranc quickly gave them back on the Pope's orders. This story might not be completely accurate, as it came from someone who supported Canterbury.

The Pope sent the argument back to a meeting of English church leaders. This meeting happened at Windsor in 1072. The leaders decided that the Archbishop of Canterbury was more important than the Archbishop of York. They also ruled that York had no rights south of the Humber River. This meant that the disputed church areas were taken from York. King William probably supported this decision. He wanted to keep the north of England connected to the rest of the country. By taking away some of York's bishops, William limited York's power. A writer named Hugh the Chanter said that by making Thomas obey Canterbury, the King removed the risk that Thomas might crown someone else as King of England, like the Danish king. However, the Windsor meeting also said that York's area included Scotland. But York couldn't really enforce this on the independent Archbishop of St Andrews in Scotland. Even though Thomas had to promise to obey Lanfranc and his successors, this promise didn't say that Canterbury was more important. It also didn't apply to future Archbishops of York.

All these decisions were confirmed in the Accord of Winchester that year. The King, a representative of the Pope, and many bishops and abbots witnessed it. Thomas then made a written promise of obedience. Lanfranc wrote to Pope Alexander II, trying to get a written paper from the Pope saying Canterbury was the most important. But Alexander said Lanfranc had to bring the case to the Pope's court again before such a paper could be given. Alexander died in 1073. His successor, Pope Gregory VII, didn't like the idea of one church being more important than others. So, the paper for Canterbury never happened. In 1073, Thomas worked with Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester, and Peter, Bishop of Chester, to make Radulf the Bishop of Orkney. This was an attempt to increase York's power in Scotland. Bishop Wulfstan often helped Thomas with church duties in parts of York's area during the 1070s, especially in places that were still unsettled after the conquest.

Thomas changed how the cathedral chapter worked during his time as archbishop. He created a group of church officials called canons, who each had their own income. Before this, the cathedral clergy lived together. But Thomas's changes allowed them to live in their own homes. Thomas also set up new roles within the cathedral, like a dean, treasurer, and precentor. He increased the number of clergy in the chapter from the three he found when he started. He also reorganized the church's lands, giving some to the chapter. He brought the idea of archdeacons to the Diocese of York. He divided the diocese into areas and put an archdeacon in charge of each. Archdeacons helped the archbishop with his duties, collected money, and ran some church courts.

Rebuilding York Minster

Shortly before Thomas became archbishop, York Minster, the main church of the archdiocese, was badly damaged in a fire on 19 September 1069. The fire also destroyed the dining hall and sleeping area for the canons. Soon after he became archbishop, Thomas had a new dining hall and sleeping area built. He also put a new roof on the cathedral. These were likely temporary fixes. Later, probably around 1075, he ordered a completely new cathedral to be built in a different spot. This new building was much larger than the old one, but it no longer exists today.

Archaeologists dug up the site between 1966 and 1973. They found that the new cathedral's design was different from most others built in England at that time. It was longer, didn't have side aisles in the main part, and had a rectangular crypt (an underground room) that was old-fashioned by 1075. Because of how the foundations were laid, it seems the whole building was planned and built in one go, with few changes. It's possible that Thomas designed his cathedral to be as different from Canterbury Cathedral as possible, perhaps because of the ongoing conflict between York and Canterbury. William of Malmesbury, a writer from the 1100s, said that Thomas finished the cathedral. This is supported by the fact that Thomas was buried in the minster in 1100. Some parts of Thomas's building can still be seen in the crypt of York Minster today.

Serving King William II

After King William the Conqueror died, Thomas remained loyal to his third son, William Rufus. Rufus inherited England instead of his older brother, Robert Curthose. Thomas supported Rufus even when his old teacher, Odo of Bayeux, led a rebellion. The Archbishop went with the King to help put down the revolt. Thomas also attended the trial in 1088 for William de St-Calais, the Bishop of Durham, who had sided with Odo. Bishop William was Thomas's only bishop under his authority, but it was Thomas who announced the court's decision.

In 1092 and again in 1093, the argument with Canterbury started up again. Thomas complained about what he felt were attacks on York's rights. The first time was about the opening of Remigius de Fécamp's new cathedral in Lincoln. The second time was about making Anselm the Archbishop of Canterbury. Thomas refused to make Anselm archbishop if Anselm was called "Primate of England." The problem was finally solved by calling Anselm the "Metropolitan" of Canterbury. A writer from Canterbury, Eadmer, who supported Anselm, said Anselm was made "primate." But Hugh the Chanter, who was from York, said the "metropolitan" title was used. Historians today are divided on which title was used. It seems both sides might have twisted the story a bit.

Herbert de Losinga was sent by Pope Urban II in 1093 to look into Thomas's promise of obedience to Lanfranc. But Herbert didn't seem to do anything about it. Also in 1093, King William II gave the Archbishops of York the right to choose the Abbot of Selby Abbey. This was to make up for York losing its claim to the Diocese of Lincoln. While Anselm was away from England after arguing with the King in 1097, Thomas made Herbert de Losinga the Bishop of Norwich, Ralph de Luffa the Bishop of Chichester, and Hervey le Breton the Bishop of Bangor. This was unusual because these areas were in Canterbury's region, and it was Anselm's right to make these new bishops. In 1100, after King William II suddenly died, his younger brother Henry took power. Thomas arrived in London too late to crown Henry I, as the ceremony had already been done by Maurice, the Bishop of London. Anselm was still away from England at this time. Thomas was angry at first, but it was explained to him that the King was worried about disorder if there was a delay. To calm him down, Thomas was allowed to crown the King publicly at a church meeting held soon after the first coronation.

Death and Legacy

Thomas died in York on 18 November 1100. People thought he was an excellent archbishop. He made sure his cathedral clergy were well cared for. He repaired the cathedral and helped improve trade in the city of York. Thomas also helped his family members succeed. One of his nephews, Thomas II of York, became Archbishop of York in 1108. Another nephew, Richard, became Bishop of Bayeux in 1107.

During his life, Thomas was praised for being very smart, for encouraging education in his church area, and for being generous. He was a great singer and wrote hymns. When he was young, he was known for being strong. In his old age, he had a reddish face and bright white hair.

Thomas wrote the words for William the Conqueror's tomb in the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen. But a writer named Orderic Vitalis felt that Thomas was chosen more for his high rank than for his writing skills. Thomas didn't get involved in the arguments about who should choose church leaders (the Investiture Crisis). However, he strongly defended York's independence against Canterbury's attempts to control all of England. Later writers, including William of Malmesbury and Hugh the Chanter, praised Thomas for his generosity, purity, elegance, and charm.