Canterbury–York dispute facts for kids

The Canterbury–York dispute was a long-running argument between two important church leaders in medieval England: the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York. This disagreement started soon after the Normans took over England in 1066. It lasted for many years.

The main point of the argument was about who had more power, or "primacy," over the other. Canterbury wanted to be in charge of York. Several Archbishops of Canterbury tried to make the Archbishops of York promise to obey them. But they never fully succeeded. York fought back by asking the kings of England and even the Pope for help.

In 1127, the main part of the dispute was mostly settled in York's favor. They did not have to promise to obey Canterbury. Later on, the argument became more about who had more status and respect.

Contents

What Was the Fight About?

The main reason for this big argument was that the Archbishops of Canterbury, after the Norman Conquest, wanted to show they had the most power. They wanted to be the "primate," meaning the top church leader, over the province of York. Canterbury used old writings to support their claims. These included a famous history book by Bede called Historia ecclesiastica gentis Angulorum. This book sometimes made it seem like Canterbury's archbishops were in charge of all the churches in the British Isles.

The dispute started with Lanfranc, who was the first Norman Archbishop of Canterbury. It turned into a never-ending fight between the two church regions over who had more importance. Historian David Carpenter said Lanfranc's actions "sucked his successors into a quagmire." This means his actions caused big problems for those who came after him. It actually made church rules weaker and hurt the unity of the kingdom. Carpenter also said that because of these arguments, the two archbishops could not even be in the same room in later centuries.

The church groups, called cathedral chapters, also played a part. They encouraged their archbishops to keep fighting. Another issue was that Canterbury's church group was made up of monks. York's group had regular priests, called canons. This added a rivalry between monks and regular priests to the dispute.

The argument also got mixed up with the `investiture controversy` in England. This was another big church argument happening at the same time. Many of the same people were involved. The kings of England could have made a decision, but they were busy with other things. They didn't really care who won Canterbury's claims. This meant there was no easy way to solve the problem. Sometimes, kings supported Canterbury to stop the north of England from rebelling. But other times, kings were fighting with Canterbury themselves.

The Popes were often asked to decide the issue. But they had their own reasons for not wanting to give one side complete power. They didn't want to fully side with Canterbury. However, Lanfranc and Anselm of Canterbury were very important and respected church leaders. So, it was hard for the Pope to rule against them. Once Anselm was no longer in office, the Popes started to support York more often. They generally tried to avoid making a final decision.

Under the Norman Kings

Lanfranc's Time

The argument started when Lanfranc became Archbishop of Canterbury. He demanded that the Archbishop of York, and other bishops, promise to obey him. This happened soon after Lanfranc became archbishop. King William I of England then suggested that Lanfranc consecrate the new Archbishop of York, Thomas of Bayeux.

Lanfranc demanded that Thomas swear to obey him as his main church leader before the ceremony. Thomas refused at first, but he eventually agreed. However, people argued about what kind of promise Thomas made. Canterbury said it was a full promise without conditions. York said it was only a personal promise to Lanfranc, not to the office of Canterbury itself.

When Thomas and Lanfranc visited Rome in 1071, Thomas brought up the power issue again. He also claimed three of Canterbury's church areas: Lichfield, Dorchester, and Worcester. Pope Alexander II sent the problem back to England. It was to be settled at a meeting called by the Pope's representative.

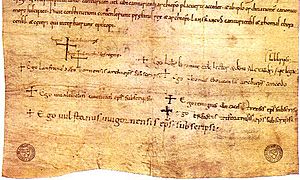

This meeting happened in Winchester in April 1072. Lanfranc won on both the power issue and the church areas. This victory was written down in the Accord of Winchester. Everyone present signed it. However, the Pope's approval of this decision did not apply to Lanfranc's future successors. It was never a full approval of the meeting's rulings. King William I supported Lanfranc at this meeting.

Thomas was given authority over the Scottish bishops as a compromise. This was an attempt to give York enough bishops under its control. This would allow future Archbishops of York to be consecrated without Canterbury's help. A consecration needed three bishops. After York's claims to Lichfield, Dorchester, and Worcester were denied, York only had one bishop under its control: the Diocese of Durham.

It's not clear why Lanfranc pushed for power over York. Some historians think it was because Thomas was a follower of Odo of Bayeux. Odo was one of Lanfranc's rivals in the English church. Another idea is that Lanfranc wanted to be in charge of the northern part of Britain. This would help him with his church reforms. Lanfranc was also likely influenced by his own church group in Canterbury. They might have wanted to regain their honor after problems with Lanfranc's predecessor, Stigand.

York had never been the main church power. It argued that such main powers were wrong in general. While Canterbury was more important than York in Anglo-Saxon times, it had never actually had legal power over York. Lanfranc's background as a monk probably also influenced him. He might have felt that the church structure should be like a monastery, with absolute obedience to a superior.

However, a big influence was likely the False Decretals. This was a collection of church rules from the ninth century. It mentioned "primates" as being like patriarchs. They were placed between the Pope and the main bishops in the church's ranking.

When Lanfranc tried to find written proof for his claims, he found no clear statement of such power. This involved using letters from Pope Gregory the Great. These letters were also mentioned in Bede's Historia. But there was a problem: Gregory's plan for the Gregorian mission said the southern church area would be based in London, not Canterbury. There was some papal evidence that Canterbury had power over the island. But these dated from before York became an archbishopric. During the Winchester meeting in 1072, papal letters were shown. It's debated whether these were fake or real.

Margaret Gibson, who wrote about Lanfranc, believes these documents existed before Lanfranc used them. Another historian, Richard Southern, thinks that parts about Canterbury's power were added to real papal letters after Lanfranc's time. Most historians agree that Lanfranc himself had nothing to do with any forgeries.

King William I supported Lanfranc in this argument. He probably felt it was important for his kingdom to have one main church province. Supporting Canterbury's power would help with this. Before conquering England, William ruled duchy of Normandy, which had one main church leader. The simple control this allowed probably made William support Canterbury. Another concern was that the north of England, where York was, was still not fully peaceful. Allowing York to be independent might lead to them crowning another king.

Thomas claimed that when Lanfranc died in 1089, his promise of obedience ended. During the long time that Canterbury had no archbishop after Lanfranc's death, Thomas performed most of the archbishop's duties in England.

Anselm's Time

When Anselm became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1093, after a long gap, the only small argument was at his consecration ceremony. This was on December 4, 1093. The argument was about the exact title Anselm would be given. It was settled quickly, but we don't know the exact title used. The two main historical sources disagree. Eadmer, Anselm's writer and a Canterbury supporter, said the title was "Primate of all Britain." Hugh the Chanter, a writer from York and a York supporter, said the title was "Metropolitan of Canterbury." Until King Henry I became king in 1100, Anselm was busy with other arguments with King William II.

It was during Anselm's time as archbishop that the power dispute became very important to his plans. Eadmer made the dispute a main part of his book, the Historia Novorum. Similarly, Hugh the Chanter made the power dispute a central theme of his book History of the Church of York.

In 1102, Pope Paschal II, who was dealing with the Investiture Controversy, tried to fix problems about `investiture` (who could appoint church leaders). He gave Anselm a special power, but only to Anselm himself, not to future archbishops. The Pope's grant also didn't clearly say that York was under Canterbury. Anselm then held a meeting in September 1102 at Westminster. Gerard, the new Archbishop of York, was there. According to Hugh the Chanter, when the bishops' seats were arranged, Anselm's was higher than Gerard's. This made Gerard kick over chairs and refuse to sit until his chair was exactly as high as Anselm's. Later in 1102, the Pope wrote to Gerard, telling him off and ordering him to make the oath to Anselm.

Gerard died in May 1108. His replacement, Thomas, was chosen within six days. However, Thomas delayed going to Canterbury to be consecrated. His church group pressured him. He also knew Anselm was sick and might die, so he could outlast him. Thomas told Anselm that his church group had forbidden him from making any oath of obedience. The canons themselves confirmed this in a letter to Anselm. Although Anselm died before Thomas submitted, one of Anselm's last letters ordered Thomas not to seek consecration until he had made the required promise. After Anselm's death, the king then pressured Thomas to submit a written promise. He eventually did.

The actual document has disappeared. As always, Eadmer and Hugh the Chanter disagree on the exact words. Eadmer claimed it was made to Canterbury and any future archbishops. Hugh claimed that Thomas added a condition to the oath. This condition made it clear that the oath could not stop the rights of the Church of York.

Thurstan's Dispute

During the time of Thurstan, who was Archbishop of York between 1114 and 1140, the dispute flared up again. Thurstan asked the Pope for help. Canterbury, under Ralph d'Escures, fought back with information from Bede and some forged documents. The Pope didn't necessarily believe the forgeries, but the argument continued for many years.

Soon after Thurstan was chosen in 1114, Ralph refused to consecrate him unless Thurstan gave a written promise of obedience, not just an oral one. Thurstan refused and promised his church group that he would not submit to Canterbury. York argued that no main bishop or archbishop could swear loyalty to anyone but the Pope. This position was sure to get support from the Pope. King Henry, however, refused to let Thurstan appeal to the Pope. This left the dispute stuck for two years. Henry didn't seem to care who won. He might have delayed hoping that Ralph and Thurstan would find a compromise. This would keep Henry from upsetting either of them.

Pressure grew, and Henry called a meeting in the spring of 1116. Henry ordered that when Thurstan arrived, he must swear to obey Canterbury. If Thurstan refused, Henry threatened to remove him from office. But, on his way to the meeting, Thurstan received a letter from the Pope. It ordered Thurstan's consecration without any promise. Although Thurstan didn't reveal the Pope's order, he kept refusing to make a promise. He resigned his position in front of the king and the meeting. But the Pope, the York church group, and even King Henry still considered Thurstan the chosen archbishop. In 1117, Ralph tried to visit Pope Paschal II about the dispute. But he couldn't actually meet the Pope. He only got a vague letter confirming Canterbury's past special rights. Since the exact rights weren't listed, the letter was useless.

Both Ralph and Thurstan attended the Council of Reims in 1119. This meeting was called by Pope Calixtus II in October. Canterbury sources say that Thurstan promised King Henry he would refuse consecration at the meeting. But York sources deny that any such promise was made. Calixtus quickly consecrated Thurstan at the start of the meeting. This angered Henry and led the king to send Thurstan away from England and Normandy. Although the Pope and king met and talked about Thurstan's situation in November 1119, nothing came of it. In March 1120, Calixtus gave Thurstan two papal documents. One was an exemption for York from Canterbury's claims, called Caritatis Bonun. The other threatened to stop all church services in England if Thurstan was not allowed to return to York. After some diplomatic efforts, Thurstan was allowed back into the king's favor and got his office back. Calixtus's documents also allowed any future Archbishops of York to be consecrated by their own bishops if the Archbishop of Canterbury refused.

In 1123, William of Corbeil, the newly chosen Archbishop of Canterbury, refused to be consecrated by Thurstan. He insisted that the ceremony include an admission that Canterbury was the primate of Britain. When Thurstan refused, William was consecrated by three of his own bishops. William then traveled to Rome to get his election confirmed, as it was being questioned. Thurstan also traveled to Rome. Both archbishops had been called to a papal meeting, but both arrived too late. Thurstan arrived shortly before William.

While there, William and his advisors showed documents to the Pope's court. They insisted these proved Canterbury's power. However, the cardinals and the court found the documents to be forgeries. What convinced the cardinals was that nine documents shown were missing `papal bulls` (official papal seals). The Canterbury group tried to explain this by saying the seals had "wasted away or were lost." Hugh the Chanter, a medieval writer from York, said that when the cardinals heard that, they laughed and made fun of the documents. He wrote they said "how miraculous it was that lead should waste away or be lost and parchment should survive." Hugh also recorded that Canterbury's attempts to achieve their goal by bribery also failed.

Pope Honorius II decided in York's favor in 1126. He found Canterbury's documents and case unconvincing. In the winter of 1126–1127, they tried to find a compromise. Canterbury agreed to give control over the church areas of Chester, Bangor, and St Asaph to York. In return, York would submit to Canterbury. This failed when William of Corbeil arrived in Rome. He told the Pope that he had not agreed to give up St Asaph. This was William's last attempt to get an oath from Thurstan.

A compromise was made in the power dispute. William of Corbeil received a `papal legateship`. This effectively gave him the powers of the primate without the Pope actually having to say Canterbury was the primate. This legateship covered not only England but Scotland as well.

A small argument happened in 1127. William of Corbeil objected to Thurstan having his bishop's cross carried in front of him in processions while Thurstan was in Canterbury's area. William also objected to Thurstan taking part in the king's crowning ceremonies. Thurstan appealed to Rome. Honorius wrote a very strong letter to William. He said that if Thurstan's reports were true, William would be punished. Thurstan then traveled to Rome. There, he got new rulings from the Pope. One ruling said that the seniority (who was more important) between the two British archbishops would go to whoever was consecrated first. Another ruling allowed the Archbishops of York to have their crosses carried in Canterbury's area.

What Happened After the First Dispute?

The most important result of this first dispute was that more and more people started asking the Pope to solve problems. This was part of a general trend to seek help and solutions from the Pope, instead of from the king's courts. This trend grew during the reigns of William II and Henry I. Also important was that the disputes pushed both York and Canterbury to try and control the churches in Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. After the issue of promises was settled, the argument turned to smaller things. These included how the two archbishops' chairs would be arranged when they were together. They also argued about the right of each to carry their bishop's cross in the other's area.

Under King Stephen

During the reign of King Stephen, the dispute briefly came up again at the Council of Reims in 1148. Theobald of Bec, who was Archbishop of Canterbury for most of Stephen's reign, attended the council. When Henry Murdac, who had just been chosen for York, did not arrive, Theobald claimed power over York at one of the early council sessions. However, Murdac was a Cistercian monk, just like Pope Eugene III, who had called the council. So, nothing more was done about Canterbury's claim. Eugene postponed any decision until Murdac was settled in his position.

Most of the time, however, Theobald was not interested in restarting the dispute. This was shown when he consecrated Roger de Pont L'Evêque, the newly chosen Archbishop of York in 1154. Theobald, at Roger's request, performed the consecration as a papal legate (the Pope's representative), not as archbishop. This avoided the question of Roger having to promise obedience.

Arguments Under King Henry II

During Thomas Becket's time as archbishop, the dispute flared up again. An added problem was that Gilbert Foliot, the Bishop of London, tried to make his church area an archbishopric. He based his case on the old plan by Gregory the Great for London to be the main city for the southern church province. Foliot was an opponent of Becket's, and this added to the dispute. Also, Becket's special papal powers specifically did not include York. When Roger de Pont L'Evêque, the Archbishop of York, crowned Henry the Young King in 1170, this made the dispute worse. It was Canterbury's special right to crown the kings of England.

The first sign of the dispute returning was at the Council of Tours in 1163. This was called by Pope Alexander III. While there, Roger and Becket argued about where their seats would be placed in the council. Roger argued that, based on Gregory the Great's plan, the archbishop who had been consecrated first had the right to the more honorable seat. Eventually, Alexander put them both on equal terms. But not before the council spent three days listening to their claims and counter-claims. Roger also told the whole history of the dispute. In 1164, Alexander gave Roger a papal legateship, but it did not include Becket's area. The Pope did, however, refuse to say that Canterbury had the main power in England. Alexander confirmed Canterbury's power on April 8, 1166. But this became less important than the special papal power given to Becket on April 24. This power, though, did not cover the church area of York. York was specifically left out.

During the reign of King Henry II, the dispute took a new form. It was about whether either archbishop could carry their special archbishop's cross throughout the whole kingdom, not just in their own area. During the time between Theobald of Bec's death and Becket's appointment, Roger had gotten papal permission to carry his cross anywhere in England. As the `Becket controversy` grew, however, Alexander asked Roger to stop doing so. This was to stop the arguments that had come from Roger doing it. Later, Alexander took back the privilege, saying it had been given by mistake.

The dispute continued between Hubert Walter and Geoffrey. They were Archbishop of Canterbury and Archbishop of York, respectively, during King Richard I's reign. Both archbishops had their special crosses carried in front of them in the other's church area. This caused angry complaints. Eventually, both church leaders tried to get King Richard to settle the matter in their favor. But Richard refused. He said this was an issue that needed to be settled by the Pope. However, no firm settlement was made until the 14th century.

The Pope continued to give special papal powers to the Archbishops of Canterbury. But after 1162, they started to specifically exclude the province of York from these powers. The only exception in the later half of the 12th century was the special power given to Hubert Walter in 1195. This covered all of England. However, this exception was more because Pope Celestine III disliked Geoffrey, who was the Archbishop of York at the time.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |