England in the High Middle Ages facts for kids

The High Middle Ages in England lasted from 1066 to 1216. This period began with the Norman Conquest and ended with the death of King John.

In 1066, William of Normandy invaded England and won the Battle of Hastings. This victory made him King of England. His rule connected England with lands in France and brought new nobles to the country. These nobles spoke French and controlled land, government, and the church. They used castles and a feudal system to keep power.

By 1087, England was a big part of the Anglo-Norman empire. Nobles owned land in England, Normandy, and Wales. After William's death, his sons fought over who would rule. William II became king of England and parts of Normandy. When he died in 1100, his younger brother, Henry I, took the throne. Henry defeated his brother Robert to unite England and Normandy again.

Henry I was a strong king. But after his only son, William Adelin, died in a shipwreck, Henry convinced his nobles to accept his daughter, Matilda, as his heir. When Henry died in 1135, Matilda's cousin, Stephen of Blois, claimed the throne. This led to a civil war called The Anarchy. Eventually, Stephen agreed that Matilda's son, Henry, would be his heir. Henry became king in 1154.

King Henry II had many lands in France. He also took control over Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. He had a big disagreement with Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, which led to Becket's murder. Later, Henry's own sons rebelled against him, with help from the King of France. Henry was forced to name his son Richard as his only heir.

Richard became king in 1189 and soon left on a Crusade. When he returned, he was captured in Germany. A huge amount of money was paid to free him in 1194. Richard spent the rest of his rule getting back his French lands. He died in 1199. His younger brother, John, became king. John fought a war against Richard's nephew, Arthur, for control of French lands. John's actions made many nobles angry. His attempt to take back Normandy failed at the Battle of Bouvines. This made him weaker in England. It led to a treaty called Magna Carta, which limited the king's power, and a war with his nobles. John's death in 1216 is seen by some as the end of the Angevin period and the start of the Plantagenet dynasty.

The Normans kept many English government ideas. But the feudal system gave more power to the king and a small group of nobles. Women's rights and roles became clearer. Noblewomen were important in culture and religion. They also played a part in politics and wars. Over time, the Normans and English started to mix. They began to see themselves as better than their Celtic neighbours. The conquest brought Norman church leaders to power. New religious groups and military orders came to England. By the early 1200s, the church was mostly independent from the state and answered to Rome. Pilgrimages were popular, and collecting relics was important for churches. England was a big part of the Second, Third, and Fifth Crusades.

Between the 9th and 13th centuries, England had a warm period. This allowed more land to be farmed. Farms were usually organized around manors. By the 11th century, a market economy was growing in England. Towns in the east and south were busy with international trade. Many new towns were built, some planned. These towns helped create guilds (groups for tradespeople) and charter fairs (special markets).

Wars were often about raiding lands and taking castles. Naval forces helped move troops and supplies. After the conquest, Normans built many timber motte and bailey and ringwork castles. These were replaced by stone castles from the 12th century. This time in history has been shown in many popular stories, including William Shakespeare's plays.

Contents

English Kings and Their Reigns

The Normans Rule England

William the Conqueror's Invasion

In 1066, King Edward the Confessor died without a clear heir. This led to a big fight over who would be the next king. Harold Godwinson, a powerful English noble, was chosen and crowned king. But two other strong rulers also claimed the throne.

Duke William of Normandy said that King Edward had promised him the crown. Harald III of Norway, also known as Harald Hardrada, claimed the throne based on an old agreement. Both William and Harald got ready to invade England.

Harold Godwinson first defeated and killed Harald Hardrada and his own brother, Tostig, at the battle of Stamford Bridge in the north. Then, William invaded with his army in the south. Harold quickly marched his tired army south to meet William. They fought at the battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. Harold was defeated and killed. William's forces quickly took control of southern England.

King William I (1066–1087)

After conquering England, William faced many challenges. There were revolts, which he put down. He also devastated the north-east of England to control it. The Normans were a small group compared to the English people. William's followers expected land and titles for their help. William said that all land belonged to him, and he could give it out as he wished. This meant that all land was "held" from the king in return for military service.

To reward his followers, William took land from English lords who had fought against him. This caused more revolts, leading to more land being taken. To stop rebellions, the Normans built many castles, mostly timber ones at first. William also gave land to the Church and appointed Norman bishops. By the time William died in 1087, England was a big part of an Anglo-Norman empire. This empire was ruled by nobles who owned land in England, Normandy, and Wales.

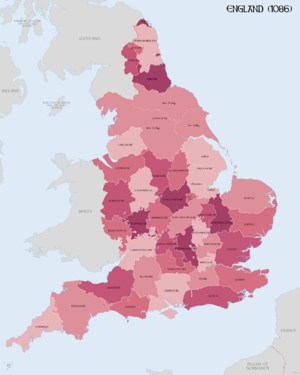

In 1085, William ordered a survey of all the land in England. This survey is known as the Domesday Book. It listed who owned land before and after the conquest, its value, and resources. This helped William keep track of his new kingdom.

King William II (1087–1100)

When William the Conqueror died in 1087, his lands were split. His oldest son, Robert Curthose, got Normandy. His younger son, William Rufus, got England. Nobles who owned land in both places wanted one ruler. They rebelled against William Rufus in 1088, wanting Robert to rule both. But Robert didn't come to England to support them. William Rufus won over the English lords with money and promises, and he defeated the rebellion.

In 1091, William invaded Normandy and defeated Robert. They later made peace, and William helped Robert against the King of France. William also had conflicts with Anselm, the Archbishop of Canterbury, over church reforms. William died while hunting in 1100.

King Henry I (1100–1135)

Even though Robert had a claim, his younger brother Henry quickly took power in England. Robert invaded in 1101, but Henry kept his control. Henry then invaded Normandy in 1105 and 1106, finally defeating Robert at the Battle of Tinchebray. Henry kept Robert imprisoned for the rest of his life.

Henry's control of Normandy was challenged by the King of France and others. They supported Robert's son, William Clito. There was a big rebellion in Normandy between 1116 and 1119. After Henry's victory at the Battle of Brémule, he made a good peace deal with the French king.

Henry was seen as a tough but effective ruler. He was good at managing the nobles in England and Normandy. In England, he used the existing Anglo-Saxon justice and tax systems, but he also made them stronger. He created the royal exchequer (a treasury department) and sent judges to travel around the country. Many of his officials were "new men" who rose through the ranks. Henry also supported church reforms.

Stephen, Matilda, and the Anarchy (1135–1154)

Henry I's only legal son, William Adelin, died in the White Ship disaster in 1120. This caused a new problem for who would be king. Henry named his daughter Matilda as his heir. But when Henry died in 1135, her cousin Stephen of Blois declared himself king.

Matilda's husband, Geoffrey, supported Matilda by invading Normandy. Matilda came to England to challenge Stephen. She was declared "Lady of the English," starting a civil war called the Anarchy. Stephen was defeated and captured at the Battle of Lincoln (1141), and Matilda became the effective ruler. But Matilda was forced to release Stephen in a hostage exchange. Stephen was crowned again. The fighting in England continued.

Matilda's son, Henry II, became very rich through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. He negotiated with the tired nobles and King Stephen. They agreed to the Treaty of Wallingford, which recognized Henry as Stephen's heir.

The Angevin Kings

King Henry II (1154–1189)

After Stephen died in 1154, Henry became the first Angevin king of England. He was also the Count of Anjou in France, adding it to his lands in Normandy and Aquitaine. England became a key part of his large "Angevin Empire" across Western Europe.

Henry took control of Brittany and made changes to its laws. He also fought campaigns against Welsh princes, making them accept his rule. When the Scottish king joined a rebellion by Henry's sons and was captured, Henry made the Scottish king swear loyalty to him.

Henry also got involved in Ireland. He helped a deposed Irish king, and then Henry himself invaded in 1171. He wanted to establish his rule and help the Pope gain more control over the Irish church. Many Irish and Anglo-Normans accepted his rule.

Henry wanted to control the Church in England more. He appointed his friend, Thomas Becket, as Archbishop of Canterbury. But Becket opposed Henry's ideas about the Church's independence. Becket fled into exile. When he returned, relations got bad again. Henry said some angry words about Becket, and three of his men murdered Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. This made Henry a pariah in Christian Europe. He had to do public penance, walking barefoot into the cathedral and being whipped by monks.

In 1173, Henry's three oldest sons and his wife rebelled against him. The King of France encouraged them. After 18 months, Henry forced them to give up. Henry tried to divide his lands among his sons, but this led to more conflict. His oldest son, also named Henry, rebelled again but died. Another son, Geoffrey, died in an accident. In 1189, his son Richard and the King of France attacked Henry II. Henry was forced to accept a humiliating peace, naming Richard as his only heir. Henry II died soon after.

King Richard I (1189–1199)

On the day of Richard's coronation, there was a terrible slaughter of Jewish people. Richard quickly sorted out his empire's affairs and left for a Third Crusade in the Middle East in early 1190. He fought in Sicily and conquered the island of Cyprus.

People had mixed opinions of Richard. He was sometimes cruel, like when he massacred 2,600 prisoners. But he was also respected for his military leadership. He won battles in the Third Crusade but failed to capture Jerusalem.

Richard was captured on his way home in 1192. A huge ransom was paid to free him in 1194. While he was away, the King of France had taken much of Normandy, and his brother John controlled other lands. Richard forgave John and took back control. Richard left England in 1194 and never returned. He fought the French king for five years to get back his lands. He died in 1199 from an arrow wound during a siege.

King John (1199–1216)

Richard had no children, which caused a problem for who would be king next. Some French lands chose Richard's nephew, Arthur. John became king in England and Normandy. The King of France again tried to weaken English control in France by supporting Arthur. John won a big victory, capturing Arthur and his rebel leaders. Arthur was later murdered, possibly by John himself. John's actions made many French nobles turn against him. This led to John losing control of most of his lands in France.

John tried to take back Normandy and Anjou. His plan was to attack France from two sides. But his allies were defeated at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. This was a very important battle for France. John had to agree to a five-year truce.

John's defeats in France made him weaker in England. His English nobles rebelled, leading to the treaty called Magna Carta. This document limited the king's power and established common law. It became very important for future legal battles. However, neither the nobles nor the king followed Magna Carta's rules. This led to the First Barons' War. The rebel nobles invited Prince Louis of France to invade. John died in 1216. After his death, Henry III, who was only nine years old, became king. The war ended with victories for Henry's supporters and a new agreement called the Treaty of Lambeth. The Magna Carta was reissued as a basis for future government.

How England Was Governed

After the Norman Conquest, the old English leaders were replaced by new Norman nobles. These new leaders, like earls and sheriffs, were all Normans. The Normans kept many English government ideas, like the tax system and law-making.

The government was like a feudal system. Nobles held their lands from the king. In return, they promised military support and swore loyalty. These nobles then gave land to smaller landowners for loyalty and military help. Peasants worked the land for their local lord. This system gave the king and top nobles more power than before. Slavery slowly ended after the conquest. However, many peasants became serfs, who were not allowed to leave their manor.

Kings used clergy members as chancellors to run royal offices. The king's military household acted as bodyguards and staff. Bishops were also important in local government. Kings Henry I and Henry II made big changes to the law, making royal law more widespread. By the 1180s, the basis for future English common law was set up. There was a permanent law court in Westminster and traveling judges. King John also increased the king's role in justice.

There were often tensions in the government. Kings needed more money for wars and rewards. They used their feudal rights to interfere with nobles' lands. This caused complaints, as people believed land should be passed down by family, not just by the king's favor. Over time, Norman nobles married into English families, and ties to Normandy weakened. By the late 1100s, it was hard to get English nobles to fight in France, and John's attempts led to civil war.

Life in Medieval England

Women's Roles

Medieval England was a patriarchal society, meaning men held most of the power. Women's lives were shaped by their social class and whether they were married, unmarried, or widowed. Women generally had fewer choices, less access to jobs, and fewer legal rights than men.

After the Norman Conquest, women's roles became more clearly defined. Some women benefited from new laws, while others lost out. Laws about widows' rights were set down, allowing free women to own property. However, women could still be forced into remarriage.

Queens and their households had less power in formal government as new government offices grew. But noblewomen, whether married or widowed, were important supporters of culture and religion. They also played a role in political and military events. Most women worked in agriculture. Roles became more divided, with men doing plowing and field management, and women often handling dairy production.

English Identity

The Normans and French who came after the conquest saw themselves as different from the English. They spoke Norman French and had their own culture. For many years, being English was linked to losing battles and being a serf. But during the 12th century, English and Normans started to mix through marriage. By the end of the 1100s, people thought the two groups were blending. The loss of Normandy in 1204 made this even stronger. French remained the language of the court and business. The English also began to see themselves as better than the Welsh, Scots, and Bretons. They thought they were civilized and Christian, while the Celtic people were seen as lazy and backward. Similar feelings were expressed about the Irish after the invasion of Ireland.

Religion in the Middle Ages

Churches and Monasteries

The Norman Conquest brought new Norman and French church leaders. Some kept old English religious ways, while others brought new practices from Normandy. Many English lands were given to monasteries in Normandy, which then created smaller monasteries in England. Monasteries became part of the feudal system, providing military support for their land. The Normans kept the English idea of monastic cathedrals, and most English cathedrals were controlled by monks within 70 years. All English cathedrals were rebuilt by the new rulers. Bishops remained powerful figures, raising armies and building castles.

New religious orders came to England. The French Cluniac order became popular. The Augustinians spread quickly from the early 1100s. Later, the Cistercians arrived, building large abbeys like Rievaulx and Fountains. By 1215, England had over 600 monastic communities. Military religious orders like the Templars and Hospitallers also gained land in England.

Church and Government

William the Conqueror got the Church's support for his invasion by promising reforms. He promoted celibacy for clergy and gave church courts more power. But he also reduced the Church's direct links to Rome, making it more accountable to the king.

Tensions grew between these practices and the Gregorian Reforms of Pope Gregory VII. These reforms wanted the clergy to be more independent from royal power and for the Pope to have more influence. Kings and archbishops often argued over appointments and religious rules. Archbishops like Anselm and Thomas Becket were forced into exile or even killed. However, by the early 1200s, the Church had largely won its fight for independence, answering mostly to Rome.

Pilgrimages and Crusades

Pilgrimages were a popular religious practice in England. People would travel to shrines or churches to ask for forgiveness or healing. Some traveled further, even to other countries. Under the Normans, important shrines like Glastonbury and Canterbury became popular pilgrimage spots. Collecting relics was important for churches, as they were believed to have healing powers and gave status to the site. Reports of miracles by local saints became common, making pilgrimages more attractive.

The idea of a religious war to Jerusalem was not new in England. While few English people joined the First Crusade, England played a big part in the Second, Third, and Fifth Crusades. Many crusaders planned to go but never left, often because they didn't have enough money. Raising money for a crusade often meant selling or mortgaging land, which affected families and the economy.

Economy and Daily Life

England's economy was mostly based on agriculture. Farmers grew crops like wheat, barley, and oats, and raised sheep, cattle, and pigs. Farmland was usually organized around manors. Land was divided between what the landowner managed directly and what peasants farmed. Peasants paid rent to the landowner with labor or with money and produce. By the 11th century, a market economy was growing in England. Towns in the east and south were involved in international trade. Many watermills were built to grind flour, freeing up people for other farm work.

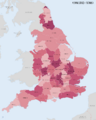

The Norman invasion caused some damage, but the English economy wasn't greatly harmed. Taxes increased, and the Normans created large royal forests for resources, protected by special laws. The next two centuries saw huge growth in the English economy. The population grew from about 1.5 million in 1086 to 4-5 million by 1300. More land was farmed to feed the growing population and produce wool for export to Europe. Many new towns were built, supporting guilds and charter fairs. Jewish financiers helped fund the growing economy. Mining also increased, with a silver boom in the 12th century helping to expand the money supply.

Warfare and Castles

Anglo-Norman warfare often involved raiding enemy lands and taking castles. Commanders tried to gain control of territory slowly. Big battles were risky and usually avoided. Armies had mounted, armored knights and infantry. Crossbowmen became more common in the 12th century. The king's permanent military household was supported by feudal levies (soldiers provided by nobles for a limited time). Mercenaries were used more and more, making wars more expensive.

Naval forces were important for moving troops and supplies, raiding enemy lands, and attacking enemy fleets. English naval power became especially important after losing Normandy in 1204, as the English Channel became a critical border.

After the conquest, Normans built many timber motte and bailey and ringwork castles to control new lands. In the 12th century, they started building more stone castles with square keeps. Royal castles controlled key towns, while noble castles controlled their estates. Castles and sieges became more advanced over time.

Art and Culture

Art and Architecture

The Norman Conquest brought French art styles, especially in illuminated manuscripts (decorated books) and wall paintings. However, English styles remained in some areas like embroidery. The famous Bayeux Tapestry shows older styles used under the new rulers. Stained glass was also used, with some examples surviving from the Norman period in churches and cathedrals like York and Canterbury.

The Normans brought their own architectural styles, preferring plain stone churches. Early Norman kings built large, simple cathedrals with ribbed vaulting. In the 12th century, Anglo-Norman style became richer, with pointed arches from French architecture replacing rounded Romanesque designs. This style is called Early English Gothic. In homes, Normans first used older English houses, then built larger stone and timber buildings. Wealthy people had houses with big ground-floor halls. Less wealthy people had simpler houses with halls on the first floor.

Stories and Music

Stories and poems written in French were popular after the Norman conquest. By the 12th century, some English history was written in French verse. Romantic poems about tournaments and courtly love became popular, spreading from Paris to England. Stories about King Arthur were also fashionable, partly because Henry II was interested in them. English was still used for local religious works and some poems in northern England, but most major works were in Latin or French. Music and singing were important for religious ceremonies, court events, and plays. From the 11th century, Gregorian chant became the standard church music.

This Period in Popular Culture

This time in history has been used in many popular stories and films. William Shakespeare's plays about medieval kings, like King John, have been very influential. Other plays, like Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and Becket (1959), focus on the death of Thomas Becket. The Lion in Winter (1966) is about Henry II and his sons.

Walter Scott's stories placed Robin Hood in the reign of Richard I, focusing on the conflict between Saxons and Normans. This set the stage for many later books and movies. Historical fiction set in medieval England is still popular. For example, Ellis Peters's The Cadfael Chronicles are detective stories set during the Anarchy. Ken Follett's best-selling The Pillars of the Earth (1989) is also set in this period. Movies often use themes from Shakespeare or Robin Hood stories, like Ivanhoe (1952). More recent films include Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) and Kingdom of Heaven (2005).

Images for kids

-

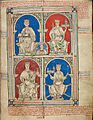

Depiction of 11th and 12th century English kings in the Chronica Majora by Matthew Paris: (from top to bottom, left to right) Henry II, Richard I, John and Henry III. Henry the Young King appears in the centre of the page.

-

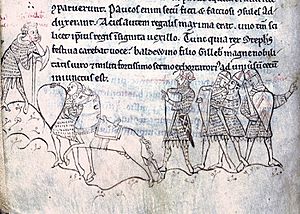

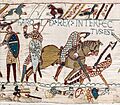

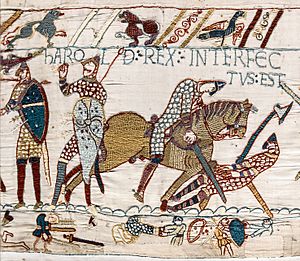

Section of the Bayeux Tapestry showing the final stages of the battle of Hastings

-

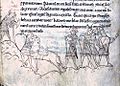

Early fourteenth-century depiction of the sinking of the White Ship on 25 November 1120

-

Twelfth-century depiction of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine holding court

-

The effigy of Richard I at Fontevraud Abbey, Anjou

-

The French victory at the battle of Bouvines doomed John's plan to retake Normandy in 1214 and led to the First Barons' War

-

Anglo-Norman twelfth-century gaming piece, illustrating soldiers presenting a sheep to a figure seated on a throne

-

A depiction of an English woman c. 1170 using a spindle and distaff, while caring for a young child

-

Fountains Abbey, one of the new Cistercian monasteries built in the twelfth century

-

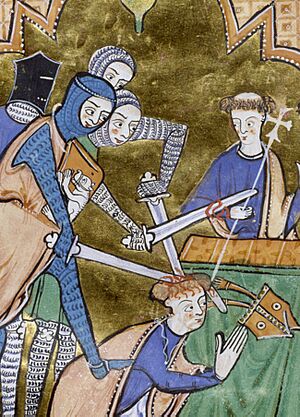

Mid-thirteenth-century depiction of the death of Archbishop Thomas Becket

-

An English serf at work digging, c. 1170

-

The Battle of Lincoln (1141) from the Historia Anglorum

-

Romanesque paintings in St Botolph's Church, Hardham

-

Salisbury Cathedral which (excluding the tower and spire) is in the Early English style

See also

- Sussex in the High Middle Ages

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |