Economics of English agriculture in the Middle Ages facts for kids

Imagine a time when almost everyone in England worked on farms! This article is about the economics of English agriculture in the Middle Ages. This period stretches from the Norman invasion in 1066 to the year 1509. During these centuries, farming was the most important part of England's economy. Even before the Normans arrived, people bought and sold farm products.

The Normans brought new rules, like serfdom, where peasants were tied to the land. These rules were added to an older farming method called the open field system. Over time, farming grew, but it struggled to feed a growing population. Then, a huge crisis hit, changing everything. By the end of this period, most farms were rented out, often managed by a new group of wealthy landowners called the gentry.

Contents

Farming in England: When the Normans Arrived

When the Normans invaded, farming was the backbone of England's economy. About 35% of England was used for growing crops. Another 25% was for grazing animals, and 15% was covered by forests. The rest was mostly moorland, fens, and heaths.

Wheat was the main crop, but farmers also grew lots of rye, barley, and oats. In fertile areas like the Thames valley and the Midlands, they also grew legumes and beans. Farmers kept sheep, cattle, oxen, and pigs. These animals were much smaller than today's breeds. Many were killed in winter because there wasn't enough food for them.

How the Manorial System Worked

Before the Normans, large estates owned by the king, bishops, and nobles were slowly being divided. Most smaller landowners lived on their land and managed their own farms. Many isolated hamlets were becoming larger villages. These villages focused on growing crops in a wide band across England.

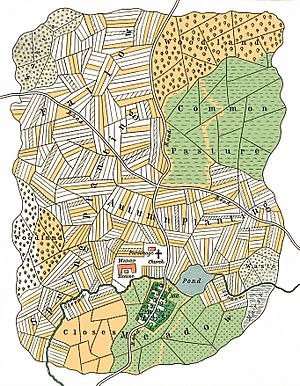

These new villages used an open field system. Fields were divided into long, narrow strips, each owned by a different farmer. Crops were rotated each year to keep the soil healthy. Local woodlands and other shared lands were carefully managed.

On a manor, some fields were managed directly by the landowner. These were called demesne lands. Most fields, however, were farmed by local peasants. These peasants paid rent to the landowner. They might pay with their labor, working on the lord's demesne fields. Or they might pay with money or farm produce.

About 6,000 watermills were built to grind flour. This freed up peasants to do other farm tasks. The early English economy wasn't just about growing enough food to survive. Many peasant farmers grew crops to sell in the growing English towns.

The Normans didn't change the manor system much at first. William the Conqueror gave huge amounts of land to his Norman nobles. This created large estates, especially near the Welsh border and in Sussex. The biggest change after the invasion was the quick drop in the number of slaves in England. Slavery had been common in the 10th century but was already decreasing.

However, the new Norman lords were tough. Wealthy Anglo-Saxon peasants quickly lost their status. They became serfs, unfree workers who couldn't leave their manor. By 1086, when the Domesday Book was made, Normans owned over 90% of the land.

Growth in the Middle Ages (1100-1290)

The 12th and 13th centuries saw a lot of economic growth in England. The population grew from about 1.5 million in 1086 to 4 or 5 million by 1300. This meant more food was needed, and England also exported raw materials to Europe.

England was mostly safe from invasions during this time. Most wars had only local or temporary effects. People in England thought of the economy as having three groups: the nobles (who fought), the peasants (who worked), and the clerics (who prayed). Merchants and trade were not seen as very important at first.

The weather was also warmer during this time, known as the Medieval Warm Period. Summer temperatures were higher, and there was slightly less rain. There's even proof that vineyards grew in southern England!

English Farming and the Land

Farming remained the most important part of England's economy. Different areas farmed in different ways, depending on the local land. For example, in the Weald, people raised animals on woodland pastures. In the Fens, people fished and hunted birds. They also made baskets and cut peat for fuel.

In places like Lincolnshire, making salt was important, even for export. Fishing became a big business along the English coast, especially in Great Yarmouth and Scarborough. Herring was a popular fish. It was salted at the coast and then sent inland or exported to Europe. Sometimes, English fishing fleets even fought each other like pirates!

Sheep were the most common farm animal. Their numbers doubled by the 14th century. Sheep became very important for their wool, especially in the Welsh borders, Lincolnshire, and the Pennines. Pigs were also popular because they could find their own food. Oxen were still the main animals for pulling ploughs. Horses started to be used more on farms in southern England by the late 12th century.

Rabbits were brought from France in the 13th century. They were raised for meat in special areas called warrens. Even with more food being produced, English farming wasn't very efficient. Wheat prices changed a lot each year, depending on the harvest. About a third of the grain grown in England was sold, much of it going to the growing towns.

How Estates Were Managed

The Normans kept the manorial system. This system divided land into demesne (land managed by the lord) and peasant lands. Peasants paid for their land with farm labor. Landowners made money by selling goods from their demesne lands. A local lord also earned money from fines and local customs. More powerful nobles made money from their own regional courts.

During the 12th century, big landowners often rented out their demesne lands for money. This was partly because prices for farm products were stable, and there was chaos during the Anarchy (1135-1153). This started to change in the 1180s and 1190s as England became more stable. In the early years of King John's rule, farm prices almost doubled. This meant more profit from demesne estates, but also higher living costs for landowners. So, landowners tried to manage their demesne lands directly again. They hired administrators and officials to run their estates.

New Farming Methods

New land was brought into use to grow more food. This included draining marshes and fens, like Romney Marsh and the Somerset Levels. Royal forests were also cleared for farming from the late 12th century. Poorer lands in the north, south-west, and Welsh Marches were also used.

The first windmills appeared in England along the south and east coasts in the 12th century. Their numbers grew in the 13th century. They added to the power available on manors. By 1300, there were over 10,000 watermills in England. They were used for grinding grain and for fulling cloth (making it thicker). Better ways of managing estates were shared. Walter de Henley wrote a famous book about it, Le Dite de Hosebondrie, around 1280. In some areas, and with some landowners, new investments and ideas greatly increased harvests. This was especially true in Norfolk, where yields eventually matched those of the 18th century.

The Church's Role in Farming

The Church owned a lot of land throughout the Middle Ages. It played a big part in developing farming and trade in the countryside. The Cistercian order arrived in England in 1128. They built about eighty new monasteries in a few years. The wealthy Augustinians also built about 150 houses. All these monasteries were supported by their farms, many in northern England.

By the 13th century, these orders owned more land. They became major economic players, both as landowners and as traders in the growing wool business. The Cistercians, in particular, developed the grange system. Granges were separate manors where monks managed all the fields directly. They became known for trying out new farming techniques. Other monasteries also had a big impact. For example, the monks of Glastonbury drained the Somerset Levels to create new pasture land.

The Knights Templar, a military religious order, also owned a lot of property in England. They earned about £2,200 a year. Most of this came from renting out rural lands for cash. They also owned some properties in London. When the Templar order was dissolved in France, King Edward II ordered their properties in England to be given to the Hospitallers in 1313. But many local landowners took the properties instead. The Hospitallers were still trying to get them back 25 years later.

The 12th century also saw efforts to limit the rights of unfree peasant workers. Their labor rents were made clearer in English Common Law. This led to the Magna Carta, which allowed feudal landowners to handle legal cases about feudal labor and fines in their own manorial courts, not the royal courts.

Big Problems: The Great Famine and the Black Death (1290-1350)

The Great Famine (1315–1317)

The Great Famine started a series of serious problems for English farming. There were bad harvests in 1315, 1316, and 1321. A sickness called murrain killed many sheep and oxen between 1319–21. A deadly fungus called ergotism also affected the remaining wheat.

During the famine, many people died. Sheep and cattle numbers dropped by half. This meant less wool and meat. Food prices almost doubled, especially for grain. Food prices stayed high for the next ten years. Salt prices also went up sharply because of the wet weather.

Several things made the crisis worse. Economic growth had already slowed down before the famine. Many peasants were struggling, with about half not having enough land to support themselves. When new land was farmed, or existing land was used too much, the soil might have become worn out.

Bad weather also played a big part. 1315-16 and 1318 had heavy rains and very cold winters. This badly affected harvests and stored food. The rains were followed by droughts in the 1320s and another harsh winter in 1321, making it hard to recover.

Diseases were also common during this time, affecting both rich and poor. The start of the Hundred Years War with France in 1337 added to the economic problems. The Great Famine stopped the population growth of the 12th and 13th centuries. It left the economy "deeply shaken, but not destroyed."

The Black Death

The Black Death epidemic first arrived in England in 1348. It came back in waves in 1360–2, 1368–9, 1375, and then less often. The most immediate impact was a huge loss of life. About 27% of the upper classes died, and 40-70% of the peasants. Even with so many deaths, few villages were completely abandoned during the epidemic itself. But many were badly affected or almost wiped out.

The authorities tried to respond in an organized way, but the economic disruption was huge. Building work stopped, and many mines closed. At first, authorities tried to control wages and keep working conditions the same as before the epidemic.

Coming after years of famine, the long-term economic effects were very serious. Unlike the rapid growth of earlier centuries, England's population would not recover for over a hundred years. This crisis would dramatically change English farming for the rest of the Middle Ages.

Later Medieval Economic Recovery (1350-1509)

The crises between 1290–1348 and the later epidemics created many challenges for England's economy. In the decades after the Black Death, economic and social problems combined with the costs of the Hundred Years War. This led to the Peasants Revolt of 1381. Even though the revolt was put down, it weakened the old feudal system. The countryside became dominated by farms, often owned or rented by the new economic class of the gentry.

English farming remained slow throughout the 15th century. Growth came instead from the greatly increased English cloth trade and manufacturing. The economic effects varied a lot by region. Generally, London, the South, and the West became richer, while the East and older cities struggled. Merchants and trade became more important to the country. Lending money with interest (usury) became more accepted. English economic ideas were increasingly influenced by Renaissance humanist theories.

Changes to Demesne Lands and the Farming System

The farming sector, still the largest part of the English economy, was changed by the Black Death. With fewer workers after the Black Death, wages for farm laborers quickly went up. They continued to grow steadily throughout the 15th century. As their incomes rose, laborers' living conditions and diets steadily improved. England's smaller population needed less food, so the demand for farm products fell.

The situation for large landowners became harder. Money from demesne lands was decreasing because demand was low and wage costs increased. Nobles also found it harder to earn money from their local courts, fines, and privileges after the Peasants Revolt of 1381. Even though they tried to increase money rents, by the end of the 14th century, rents from peasant lands were also falling. Revenues dropped as much as 55% between the 1380s and 1420s.

Noble and church landowners responded in different ways. They started to invest much less in farming. Land was increasingly taken out of production completely. In some cases, entire settlements were abandoned. Nearly 1,500 villages were lost during this period. Landowners also stopped directly managing their demesne lands, a system that began in the 1180s. Instead, they started "farming" out large blocks of land for fixed money rents. At first, animals and land were rented together, but this became impractical. So, contracts for farms focused only on land.

As the large estates changed, a new economic group, the gentry, became important. Many of them benefited from the new farming system. Land ownership remained very unequal. Estimates suggest that English nobles owned 20% of the land, the Church and Crown 33%, the gentry 25%, and peasant farmers owned the remaining 22%. Farming itself continued to improve. The loss of many English oxen to the murrain sickness during the crisis led to more horses being used to plough fields in the 14th century. This was a big improvement over older methods.

See also

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |