Economy of England in the Middle Ages facts for kids

The economy of medieval England was shaped by three main groups: the clergy (who prayed), knights (who fought), and peasants (who worked the land). Over the five centuries of the Middle Ages, England's economy first grew, then faced big challenges. These challenges led to major changes in how people lived and worked. By the end of this time, England had a growing group of English traders and businesses.

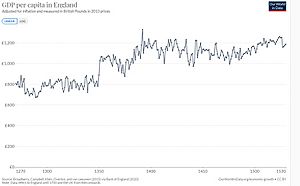

The 12th and 13th centuries saw a huge growth in the English economy. This was partly because the population grew from about 1.5 million in 1086 (when the Domesday Book was made) to between 4 and 5 million by 1300. England was mostly an agricultural country. The rights of big landowners and the duties of serfs (unfree peasants) became clearer in English law.

More land was used for farming, often taken from royal forests. This helped feed the growing population or produce wool for export to Europe. Many new towns, some of them planned, appeared across England. These towns helped create guilds (groups of skilled workers), charter fairs (special markets), and other important medieval groups.

Jewish financiers, who came to England with William the Conqueror, played a big part in the growing economy. New religious groups like the Cistercian and Augustinian orders also became important in the wool trade in the north. Mining increased, especially with a silver boom in the 12th century, which helped create a fast-growing money system.

Economic growth started to slow down by the late 13th century. This was due to too many people, not enough land, and tired soils. The Great Famine of 1315–17 caused many deaths and stopped population growth. Then, the Black Death in 1348 killed about half of England's people. This had huge effects on the economy.

The farming sector shrank. Higher wages, lower prices, and smaller profits led to the end of the old demesne system (where landowners directly managed their farms). A new system of renting land for cash began. The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 challenged the old feudal system. It also limited how much the king could tax people for the next century.

The 15th century saw the growth of the English cloth industry. A new group of international English merchants grew, mostly in London and the South-West. They became rich while older towns in the east shrank. These new trading systems led to the decline of many international fairs and the rise of chartered companies. Along with better metalworking and shipbuilding, these changes marked the end of the medieval economy and the start of the early modern period in England.

Contents

Norman Rule and Early Economy (1066–1100)

William the Conqueror took over England in 1066. He defeated King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings and brought the country under Norman rule. After this, there were tough military actions, like the Harrying of the North in 1069–70, to spread Norman power across northern England.

William's government was largely feudal. This meant that owning land was tied to serving the king. But in many ways, the invasion did not change the English economy much. Most of the damage from the invasion was in the north and west. Some areas were still called "wasteland" in 1086. Many important parts of England's farming and money systems stayed the same for decades after the conquest.

Farming and Mining in Early Norman England

How English Farms Worked

Farming was the biggest part of the English economy when the Normans invaded. Twenty years after the invasion, 35% of England was arable land (for growing crops). 25% was used for pasture (grazing animals). 15% was covered by woodlands, and the rest was mostly moorland, fens, and heaths.

Wheat was the most important crop. But rye, barley, and oats were also widely grown. In fertile areas like the Thames Valley, the Midlands, and eastern England, legumes and beans were also grown. Sheep, cattle, oxen, and pigs were kept on English farms. Most of these animals were smaller than today's breeds and many were killed in winter.

The Manorial System

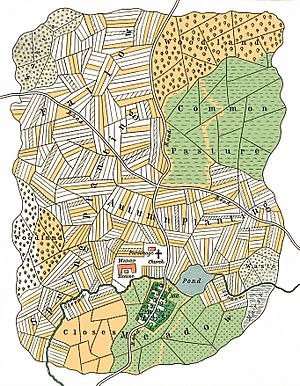

Before the Norman invasion, England's large estates, owned by the king, bishops, monasteries, and thegns (nobles), had slowly been divided. Most smaller landowners lived on their properties and managed their own lands. Before the Normans, there was a move from small, isolated farms to larger villages. These villages focused on growing crops in a band across England.

These new villages used an open field system. Fields were divided into small strips of land, each owned by an individual. Crops were rotated in the fields each year. Local woodlands and other common lands were carefully managed. Farmland on a manor was split. Some fields were managed directly by the landowner (called demesne land). Most fields were farmed by local peasants. They paid rent to the landowner by working on the lord's demesne fields or by giving cash or produce. About 6,000 watermills were built to grind flour. This freed up peasants for other farm work. The early English economy was not just about growing enough to survive. Many peasant farmers grew crops to sell in the early English towns.

The Normans did not change the manor or village economy much at first. William gave large areas of land to Norman nobles. This created huge estates in some places, especially along the Welsh Marches and in Sussex. The biggest change after the invasion was the quick drop in the number of slaves in England. In the 10th century, there were many slaves, but their numbers had already started to fall. However, the new Norman nobles were harsh landlords. Wealthier, more independent Anglo-Saxon peasants quickly became poorer. They joined the ranks of unfree workers, or serfs. These serfs were not allowed to leave their manor or find other jobs. Anglo-Saxon nobles who survived the invasion were quickly absorbed into the Norman elite or lost their wealth.

Creating Royal Forests

The Normans also created royal forests. In Anglo-Saxon times, there were special woods for hunting called "hays." But Norman forests were much larger and protected by law. These new forests were not always heavily wooded. They were defined by the king's protection and use. Norman forests were under special royal law. This forest law was "harsh and unfair, purely based on the King's will."

Forests were meant to provide the king with hunting grounds, raw materials, goods, and money. Income from forest rents and fines became very important. Forest wood was used for castles and royal ship building. Some forests were key for mining, like iron mining in the Forest of Dean and lead mining in the Forest of High Peak. Other groups also depended on forests. Many monasteries had special rights in certain forests, for example, for hunting or cutting trees. Along with royal forests, many locally owned parks and chases were quickly created.

Trade, Manufacturing, and Towns

Even though England was mostly rural, it had several old, important towns in 1066. A lot of trade passed through eastern towns like London, York, Winchester, Lincoln, Norwich, Ipswich, and Thetford. Much of this trade was with France, the Low Countries, and Germany. But the North-East of England also traded with places as far away as Sweden. Cloth was already being imported to England before the invasion through the mercery trade.

Some towns, like York, suffered from Norman attacks during William's northern campaigns. Other towns saw many houses torn down to make space for new motte and bailey castles, as happened in Lincoln. The Norman invasion also brought big economic changes with the arrival of the first Jews in English cities. William I brought wealthy Jews from Rouen in Normandy to live in London. They were meant to provide financial services for the king. In the years right after the invasion, a lot of wealth was taken from England by the Norman rulers and invested in Normandy. This made William very rich.

The minting of coins was spread out in the Saxon period. Every town was supposed to have a mint and a place for trading metal. However, the king strictly controlled these moneyers, and coin dies could only be made in London. William kept this system and created high-quality Norman coins. This led to the term "sterling" for the Norman silver coins.

Government and Taxes

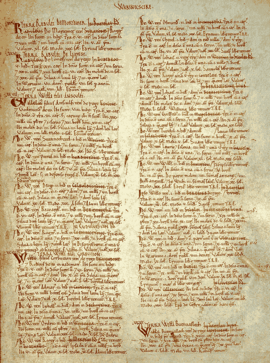

William I continued the Anglo-Saxon system where the king got money from customs duties, profits from making new coins, fines, profits from his own lands, and a land tax called the geld. William kept this system, using his new sheriffs to collect the geld and increasing taxes on trade. William was also famous for ordering the Domesday Book in 1086. This huge document tried to record the economic state of his new kingdom.

Mid-Medieval Growth (1100–1290)

The 12th and 13th centuries were a time of huge economic growth in England. The population grew from about 1.5 million in 1086 to around 4 or 5 million by 1300. This led to more farm production and the export of raw materials to Europe. Unlike the previous two centuries, England was fairly safe from invasion. Except for the years of the Anarchy, most wars had only local economic effects or were only temporarily disruptive.

English economic ideas remained traditional. They saw the economy as having three groups: the ordines (nobles who fought), laboratores (peasants who worked), and oratores (clerics who prayed). Trade and merchants were not seen as important in this model and were often criticized early in this period. However, they became more accepted by the end of the 13th century.

Farming, Fishing, and Mining

English Farming and the Land

Farming remained the most important part of the English economy during the 12th and 13th centuries. English farming varied greatly depending on local geography. In areas where grain could not be grown, other resources were used. For example, in the Weald, farming focused on grazing animals in woodland pastures. In the Fens, fishing and bird-hunting were common, along with basket-making and peat-cutting.

In some places, like Lincolnshire and Droitwich, salt production was important, including for export. Fishing became a big trade along the English coast, especially in Great Yarmouth and Scarborough. The herring was a very popular catch. Salted at the coast, it could then be sent inland or exported to Europe. Piracy between rival English fishing fleets sometimes happened.

Sheep were the most common farm animal in England during this time, their numbers doubling by the 14th century. Sheep became increasingly used for wool, especially in the Welsh Marches, Lincolnshire, and the Pennines. Pigs remained popular on farms because they could find their own food. Oxen were still the main animals for ploughing. Horses were used more widely on farms in southern England towards the end of the 12th century. Rabbits were brought from France in the 13th century and raised for their meat in special warrens.

The basic productivity of English farming remained low, even with more food production. Wheat prices changed a lot each year, depending on local harvests. Up to a third of the grain grown in England could be sold, and much of it went to the growing towns. Even the richest peasants spent most of their money on housing and clothes, with little left for other personal items. Records of household goods show most people had only "old, worn-out and mended utensils" and tools.

The royal forests grew larger for much of the 12th century, then shrank in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Henry I made royal forests bigger, especially in Yorkshire. After the Anarchy (1135–53), Henry II continued to expand the forests until they covered about 20% of England. In 1217, the Charter of the Forest was created. This was partly to reduce the harshness of royal forest laws. It set up clearer fines and punishments for peasants who illegally hunted or cut trees in the forests. By the end of the century, the king was pressured to make the royal forests smaller. This led to the "Great Perambulation" around 1300. This greatly reduced the size of the forests. By 1334, they were only about two-thirds of their size in 1250. The king's income from the shrinking forests dropped a lot in the early 14th century.

How Estates Were Managed

The Normans kept and strengthened the manorial system. This system divided land between the demesne (land managed directly by the lord) and peasant lands (paid for with farm labor). Landowners could make money from selling goods from their demesne lands. A local lord could also expect income from fines and local customs. More powerful nobles made money from their own regional courts and rights.

During the 12th century, major landowners often rented out their demesne lands for money. This was because prices for farm goods were stable and there was chaos during the Anarchy (1135–1153). This practice started to change in the 1180s and 1190s, helped by greater political stability. In the first years of King John's rule, farm prices almost doubled. This increased potential profits on demesne estates but also raised the cost of living for landowners. Landowners now tried to bring their demesne lands back under direct management. They created a system of administrators and officials to run their new estates.

New land was brought into use to meet the demand for food. This included drained marshes and fens, like Romney Marsh, the Somerset Levels, and the Fens. Royal forests were also used from the late 12th century onwards. Poorer lands in the north, south-west, and the Welsh Marches were also farmed. The first windmills in England started to appear along the south and east coasts in the 12th century, growing in number in the 13th. They added to the mechanical power available to the manors. By 1300, it's estimated there were over 10,000 watermills in England, used for grinding corn and for fulling cloth. Fish ponds were created on most estates to provide freshwater fish for nobles and the church. These ponds were very expensive to build and maintain. Better ways of running estates became known. Walter de Henley's famous book Le Dite de Hosebondrie, written around 1280, helped popularize them. In some areas and under some landowners, investment and new ideas greatly increased yields through better ploughing and fertilizers. This was especially true in Norfolk, where yields eventually matched 18th-century levels.

The Church's Role in Farming

The Church in England owned a lot of land throughout the medieval period. It played an important part in developing farming and rural trade in the first two centuries of Norman rule. The Cistercian order first arrived in England in 1128. They set up about 80 new monastic houses over the next few years. The wealthy Augustinians also established themselves and grew to about 150 houses. All these were supported by farm estates, many in northern England. By the 13th century, these and other orders were buying new lands. They became major economic players both as landowners and as middlemen in the growing wool trade.

The Cistercians, in particular, led the development of the grange system. Granges were separate manors where the fields were all farmed by monastic officials. They were not divided between demesne and rented fields. Granges became known for trying new farming methods during this time. Elsewhere, many monasteries had a big economic impact on the land. For example, the monks of Glastonbury Abbey were responsible for draining the Somerset Levels to create new pasture land.

The military crusading order of the Knights Templar also owned a lot of property in England. They brought in about £2,200 per year before their fall. This property included mostly rural lands rented out for cash, but also some city properties in London. After the Templar order was dissolved in France by Philip IV of France, Edward II ordered their properties in England to be taken and given to the Knights Hospitaller in 1313. But in reality, many properties were taken by local landowners. The Hospitallers were still trying to get them back twenty-five years later.

The Church was responsible for the system of tithes. This was a tax of 10% on "all farm produce... other natural products gained by work... wages received by servants and laborers, and the profits of rural merchants." Tithes collected as produce could be used by the recipient or sold/traded for other goods. The tithe was quite a burden for the average peasant, though often the actual tax was less than 10%. Many clergy moved to towns as cities grew. By 1300, about one in twenty city dwellers was a clergyman. One effect of the tithe was to move a lot of farm wealth into the cities, where these urban clergy then spent it. The need to sell tithe produce that local clergy couldn't use also helped trade grow.

Growth of Mining

Mining was not a huge part of the English medieval economy. But the 12th and 13th centuries saw more demand for metals in the country. This was thanks to big population growth and building construction, including the great cathedrals and churches. Four metals were mined for sale in England during this time: iron, tin, lead, and silver. Coal was also mined from the 13th century onwards, using different refining methods.

Iron mining happened in several places. The main English center was the Forest of Dean, as well as in Durham and the Weald. Some iron to meet English demand was also imported from Europe, especially by the late 13th century. By the end of the 12th century, the older method of getting iron ore through strip mining was joined by more advanced techniques. These included tunnels, trenches, and bell-pits. Iron ore was usually processed locally at a bloomery. By the 14th century, the first water-powered iron forge in England was built at Chingley. Because woodlands were shrinking and the cost of wood and charcoal increased, demand for coal grew in the 12th century. Coal began to be produced commercially from bell-pits and strip mining.

A silver boom happened in England after silver was found near Carlisle in 1133. Huge amounts of silver were produced from mines across Cumberland, Durham, and Northumberland. Up to three to four tonnes of silver were mined each year. This was more than ten times the previous yearly production across all of Europe. The result was a local economic boom and a major boost to 12th-century royal money.

Tin mining was centered in Cornwall and Devon. It used alluvial deposits (found in riverbeds) and was controlled by special Stannary Courts and Parliaments. Tin was a valuable export good, first to Germany and then later in the 14th century to the Low Countries. Lead was usually mined as a side product of silver mining. There were lead mines in Yorkshire, Durham, and the north, as well as in Devon. Lead mines were economically weak. They usually survived because they were supported by silver production.

Trade, Manufacturing, and Towns

How English Towns Grew

After the Anarchy ended, the number of small towns in England began to increase sharply. By 1297, 120 new towns had been started. By 1350, when this growth mostly stopped, there were about 500 towns in England. Many of these new towns were planned. Richard I created Portsmouth. King John founded Liverpool. Later kings created Harwich, Stony Stratford, Dunstable, Royston, Baldock, Wokingham, Maidenhead, and Reigate. New towns were usually placed near trade routes, not for defense. Their streets were laid out to make it easy to reach the town's market. A growing number of England's people lived in cities. Estimates suggest this rose from about 5.5% in 1086 to up to 10% in 1377.

London had a special place in the English economy. Nobles bought and used many luxury goods and services in the capital. As early as the 1170s, London markets offered exotic products like spices, incense, palm oil, gems, silks, furs, and foreign weapons. London was also an important center for industry. It had many blacksmiths making a wide range of goods, including decorative ironwork and early clocks. Pewter-working, using English tin and lead, was also common in London during this time.

By the end of the 13th century, provincial towns also had many trades. A large town like Coventry, for example, had over three hundred different specialized jobs. A smaller town like Durham could support about sixty different professions. The increasing wealth of the nobility and the church was seen in the widespread building of cathedrals and other grand buildings in larger towns. These used lead from English mines for roofing.

Land transport remained much more expensive than river or sea transport. Many towns during this period, including York, Exeter, and Lincoln, were connected to the oceans by navigable rivers. They could act as seaports. Bristol's port came to dominate the profitable wine trade with Gascony by the 13th century. But shipbuilding generally remained small and not very important to England's economy at this time. Transport was still very costly compared to the total price of products. By the 13th century, groups of common carriers ran carting businesses. Carting brokers existed in London to connect traders and carters. They used the four major land routes across England: Ermine Street, the Fosse Way, Icknield Street, and Watling Street. Many bridges were built during the 12th century to improve the trade network.

In the 13th century, England mostly supplied raw materials for export to Europe, rather than finished goods. There were some exceptions, like very high-quality cloths from Stamford and Lincoln, including the famous "Lincoln Scarlet" dyed cloth. Despite royal efforts to encourage it, hardly any English cloth was being exported by 1347.

More Money in Circulation

There was a gradual reduction in the number of places allowed to mint coins in England. Under Henry II, only 30 towns could still use their own moneyers. Controls continued to tighten throughout the 13th century. By the reign of Edward I, there were only nine mints outside London. The king created a new official called the Master of the Mint to oversee these and the thirty furnaces operating in London to meet the demand for new coins.

The amount of money in circulation greatly increased during this period. Before the Norman invasion, there was about £50,000 in coins. But by 1311, this had risen to over £1 million. At any given time, though, much of this money might be stored for military campaigns or sent overseas for payments. This could cause temporary drops in prices (deflation) as coins stopped moving within the English economy. One result of the growing number of coins was that they had to be made in large quantities. They were moved in barrels and sacks and stored in local treasuries for the king's use as he traveled.

The Rise of Guilds

The first English guilds appeared in the early 12th century. These guilds were groups of craftsmen who managed their local affairs. This included "prices, quality of work, the well-being of their workers, and stopping unfair practices." Among these early guilds were the "guilds merchants." They ran the local markets in towns and represented the merchant community in talks with the king. Other early guilds included "craft guilds," representing specific trades. By 1130, there were major weavers' guilds in six English towns, as well as a fullers' guild in Winchester. Over the following decades, more guilds were created. They often became more involved in both local and national politics. However, the guilds merchants were largely replaced by official groups set up by new royal charters.

Craft guilds needed stable markets and fair income and opportunities among their members to work well. By the 14th century, these conditions were less common. The first problems were seen in London, where the old guild system began to break down. More trade was happening at a national level, making it hard for craftsmen to both make goods and trade them. There were also growing differences in income between richer and poorer craftsmen. As a result, under Edward III, many guilds became companies or livery companies. These were chartered companies focused on trade and finance, leaving the guild structures to represent the interests of smaller, poorer manufacturers.

Merchants and Charter Fairs

This period also saw the growth of charter fairs in England, which were most popular in the 13th century. From the 12th century onwards, many English towns got a charter from the king. This allowed them to hold a yearly fair, usually serving regional or local customers and lasting for two or three days. This practice increased in the next century. Over 2,200 charters were given for markets and fairs by English kings between 1200 and 1270.

Fairs became more popular as the international wool trade grew. The fairs allowed English wool producers and ports on the east coast to meet visiting foreign merchants. This helped them avoid English merchants in London who wanted to make a profit as middlemen. At the same time, wealthy magnate (powerful noble) consumers in England began to use the new fairs. They bought goods like spices, wax, preserved fish, and foreign cloth in large amounts from international merchants at the fairs. This again bypassed the usual London merchants.

Some fairs grew into major international events. They followed a set schedule during the economic year. For example, the Stamford fair was in Lent, St Ives' in Easter, Boston's in July, Winchester's in September, and Northampton's in November. Many smaller fairs happened in between. Although not as large as the famous Champagne fairs in France, these English "great fairs" were still huge events. St Ives' Great Fair, for example, attracted merchants from Flanders, Brabant, Norway, Germany, and France for a four-week event each year. This turned the normally small town into "a major commercial center."

The structure of the fairs showed how important foreign merchants were to the English economy. By 1273, only one-third of the English wool trade was actually controlled by English merchants. Between 1280 and 1320, Italian merchants mostly controlled the trade. But by the early 14th century, German merchants started to compete seriously with the Italians. The Germans formed a self-governing group of merchants in London called the "Hanse of the Steelyard" – which became the Hanseatic League. Their role was confirmed under the Great Charter of 1303, which excused them from paying the usual tolls for foreign merchants. One response to this was the creation of the Company of the Staple. This was a group of merchants set up in English-held Calais in 1314 with royal approval. They were given a monopoly (sole right) on wool sales to Europe.

Jewish Contribution to the Economy

The Jewish community in England continued to provide important money-lending and banking services. These services were otherwise banned by usury laws (laws against charging interest on loans). The community grew in the 12th century with Jewish immigrants fleeing fighting around Rouen. The Jewish community spread beyond London to eleven major English cities. These were mainly the big trading centers in eastern England with working mints. All had suitable castles to protect the often persecuted Jewish minority. By the time of the Anarchy and the reign of King Stephen, the communities were thriving and lending money to the king.

Under Henry II, the Jewish financial community continued to get richer. All major towns had Jewish centers, and even smaller towns, like Windsor, saw visits by traveling Jewish merchants. Henry II used the Jewish community as "tools for collecting money for the Crown" and placed them under royal protection. The Jewish community at York lent a lot of money to fund the Cistercian order's land purchases and became very prosperous. Some Jewish merchants became extremely wealthy. Aaron of Lincoln was so rich that after his death, a special royal department had to be set up to sort out his financial holdings.

By the end of Henry's reign, the king stopped borrowing from the Jewish community. Instead, he started an aggressive campaign of tallage (a type of tax) and fines. Financial and anti-Jewish violence grew under Richard I. After the massacre of the York community, where many financial records were destroyed, seven towns were chosen to separately store Jewish bonds and money records. This arrangement eventually became the Exchequer of the Jews. After a peaceful start to John's reign, the king again began to demand money from the Jewish community. He imprisoned wealthier members, including Isaac of Norwich, until a huge new tax was paid. During the First Barons' War of 1215–17, Jews faced new anti-Jewish attacks. Henry III brought some order back, and Jewish money-lending became successful enough again to allow new taxation. The Jewish community became poorer towards the end of the century and was finally expelled from England in 1290 by Edward I. Foreign merchants largely replaced them.

Late Medieval Economic Recovery (1350–1509)

The events of the crisis between 1290 and 1348 and the later epidemics created many challenges for the English economy. In the decades after the disaster, the economic and social problems from the Black Death combined with the costs of the Hundred Years' War to cause the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Although the revolt was put down, it weakened many parts of the feudal economic system. The countryside became dominated by estates organized as farms, often owned or rented by the new economic class of the gentry.

The English farming economy remained slow throughout the 15th century. Growth at this time came from the greatly increased English cloth trade and manufacturing. The economic effects of this varied a lot from region to region. But generally, London, the South, and the West became richer, while the Eastern and older cities declined. The role of merchants and trade became increasingly seen as important to the country. Charging interest on loans (usury) gradually became more accepted. English economic ideas were increasingly influenced by Renaissance humanist theories.

Government and Taxes

Even before the first Black Death outbreak ended, authorities tried to stop wages and prices from rising. Parliament passed the emergency Ordinance of Labourers in 1349 and the Statute of Labourers in 1351. Efforts to control the economy continued as wages and prices rose, putting pressure on landowners. In 1363, parliament tried unsuccessfully to control craft production, trading, and selling. A growing amount of the royal courts' time was spent enforcing the failing labor laws – as much as 70% by the 1370s. Many landowners tried to strictly enforce rents paid through farm service rather than money, using their local manor courts. This led to many village communities trying to legally challenge local feudal practices, using the Domesday Book as a legal basis for their claims. With the wages of the lower classes still rising, the government also tried to control demand and spending by bringing back sumptuary laws in 1363. These laws banned the lower classes from consuming certain products or wearing high-status clothes. This showed how important high-quality breads, ales, and fabrics were for showing social class in the late medieval period.

The 1370s also saw the government struggling to pay for the war with France. The overall impact of the Hundred Years War on the English economy is still debated. Some suggest that the high taxes needed for the conflict "shrank and depleted" the English economy. Others argue for a smaller or even neutral economic impact. The English government clearly found it hard to pay for its army. From 1377, it turned to a new system of poll taxes. These aimed to spread the costs of taxation across all of English society.

The Peasants' Revolt of 1381

One result of the economic and political tensions was the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Widespread rural unhappiness led to thousands of rebels invading London. The rebels had many demands. These included the effective end of the feudal system of serfdom and a limit on rural rents. The violence that followed surprised the political classes. The revolt was not fully put down until the autumn. Up to 7,000 rebels were executed afterwards.

As a result of the revolt, parliament stopped using the poll tax. Instead, it focused on indirect taxes, mainly on foreign trade. These taxes brought in 80% of tax revenues from wool exports. Parliament continued to collect direct taxes at historically high levels until 1422, though they reduced them in later years. As a result, later kings found their tax revenues uncertain. Henry VI had less than half the yearly tax revenue of the late 14th century. England's kings became more dependent on borrowing and forced loans to cover the gap between taxes and spending. Even then, they faced later rebellions over tax levels. These included the Yorkshire rebellion of 1489 and the Cornish rebellion of 1497 during the reign of Henry VII.

Farming, Fishing, and Mining

End of Demesne and Rise of Farming System

The farming sector of the English economy, still the largest, was changed by the Black Death. With fewer workers after the Black Death, wages for farm laborers quickly increased and continued to grow steadily throughout the 15th century. As their incomes rose, laborers' living conditions and diet steadily improved. A trend for laborers to eat less barley and more wheat and rye, and to replace bread with more meat, had been clear even before the Black Death, but it became stronger during this later period.

However, England's much smaller population needed less food, and the demand for farm products fell. The position of larger landowners became increasingly difficult. Income from demesne lands was shrinking as demand remained low and wage costs increased. Nobles also found it harder to raise money from their local courts, fines, and privileges after the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Despite attempts to increase money rents, by the end of the 14th century, rents from peasant lands were also falling. Income dropped as much as 55% between the 1380s and 1420s.

Noble and church landowners responded in different ways. They started to invest much less in farming, and land was increasingly taken out of production completely. In some cases, entire settlements were abandoned, and nearly 1,500 villages were lost during this period. Landowners also stopped directly managing their demesne lands, a practice that had begun in the 1180s. Instead, they started "farming" out large blocks of land for fixed money rents. At first, livestock and land were rented out together under "stock and lease" contracts. But this became impractical, and contracts for farms focused purely on land. Many rights to church parish tithes were also "farmed" out in exchange for fixed rents. This process was encouraged by the trend of tithe revenues being increasingly "appropriated" (taken) by central church authorities, rather than being used to support local clergy. About 39% of parish tithes had been centralized this way by 1535. As the major estates changed, a new economic group, the gentry, became clear. Many of them benefited from the opportunities of the farming system. Land ownership remained very unequal. Estimates suggest that English nobles owned 20% of English lands, the Church and Crown 33%, the gentry 25%, and the rest was owned by peasant farmers. Farming itself continued to innovate. The loss of many English oxen to disease in the crisis increased the number of horses used to plough fields in the 14th century, a big improvement on older methods.

Forests, Fishing, and Mining

The royal forests continued to shrink in size and decline in economic importance after the Black Death. Royal enforcement of forest rights and laws became harder after 1348 and certainly after 1381. By the 15th century, the royal forests were a "shadow of their former selves" in size and economic importance. In contrast, the English fishing industry continued to grow. By the 15th century, local merchants and financiers owned fleets of up to a hundred fishing vessels operating from key ports. Herring remained a key fish catch. However, as demand for herring fell with rising wealth, fleets started to focus instead on cod and other deep-sea fish from Icelandic waters. Despite being vital to the fishing industry, salt production in England decreased in the 15th century due to competition from French producers. The use of expensive freshwater fish ponds on estates began to decline during this period. More gentry and nobles chose to buy freshwater fish from commercial river fisheries.

Mining generally did well at the end of the medieval period. This was helped by strong demand for manufactured and luxury goods. Cornish tin production dropped sharply during the Black Death itself, causing prices to double. Tin exports also fell catastrophically but recovered over the next few years. By the turn of the 16th century, the available alluvial tin deposits in Cornwall and Devon had started to decrease. This led to the start of bell and surface mining to support the tin boom that had happened in the late 15th century. Lead mining increased, and output almost doubled between 1300 and 1500. Wood and charcoal became cheaper again after the Black Death, and coal production declined as a result, remaining low for the rest of the period. Nevertheless, some coal production was happening in all major English coalfields by the 16th century. Iron production continued to increase. The Weald in the South-East started to use water-power more, and it overtook the Forest of Dean in the 15th century as England's main iron-producing region. The first blast furnace in England, a major technical step forward in metal smelting, was created in 1496 in Newbridge in the Weald.

Trade, Manufacturing, and Towns

Shrinking Towns

The percentage of England's population living in towns continued to grow. But in actual numbers, English towns shrank significantly because of the Black Death, especially in the formerly rich east. The importance of England's Eastern ports declined over the period. Trade from London and the South-West became more significant. Increasingly complex road networks were built across England. Some involved building up to thirty bridges to cross rivers and other obstacles.

However, it remained cheaper to move goods by water. As a result, timber was brought to London from as far away as the Baltic Sea. Stone from Caen was brought across the Channel to Southern England. Shipbuilding, especially in the South-West, became a major industry for the first time. Investment in trading ships like cogs was probably the single biggest form of late medieval investment in England.

Rise of the Cloth Trade

Cloth made in England increasingly dominated European markets during the 15th and early 16th centuries. England exported almost no cloth at all in 1347. But by 1400, about 40,000 cloths a year were being exported. The trade reached its first peak in 1447 when exports hit 60,000. Trade fell slightly during the serious economic downturn of the mid-15th century. But it picked up again and reached 130,000 cloths a year by the 1540s. The main areas for weaving in England shifted westwards. They moved towards the Stour Valley, the West Riding, the Cotswolds, and Exeter. This was away from the older weaving centers in York, Coventry, and Norwich.

The wool and cloth trade was now mostly run by English merchants themselves, rather than by foreigners. Increasingly, the trade also passed through London and the ports of the South-West. By the 1360s, 66–75% of the export trade was in English hands. By the 15th century, this had risen to 80%. London handled about 50% of these exports in 1400, and as much as 83% of wool and cloth exports by 1540. The number of chartered trading companies in London continued to grow. Examples include the Worshipful Company of Drapers or the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London. English producers began to offer credit to European buyers, rather than the other way around. Charging interest (usury) grew during this period, and few cases were prosecuted by the authorities.

There were some setbacks. English merchants tried to break directly into the Baltic markets, bypassing the Hanseatic League. But this failed due to the political chaos of the Wars of the Roses in the 1460s and 1470s. The wine trade with Gascony fell by half during the war with France. The eventual loss of the province ended English control of the business. It also caused temporary problems for Bristol's prosperity until wines started to be imported through the city a few years later. Indeed, the disruption to both the Baltic and Gascon trade led to a sharp reduction in the consumption of furs and wine by the English gentry and nobility during the 15th century.

There were advances in manufacturing, especially in the South and West. Despite some French attacks, the war created much prosperity along the coast. This was thanks to the huge spending on shipbuilding during the war. The South-West also became a center for English piracy against foreign vessels. Metalworking continued to grow, especially pewter working, which generated exports second only to cloth. By the 15th century, pewter working in London was a large industry, with a hundred pewter workers recorded in London alone. Pewter working had also spread from the capital to eleven major cities across England. London goldsmithing remained important but grew little, with about 150 goldsmiths working in London during this time. Iron-working continued to expand. In 1509, the first cast-iron cannon was made in England. This was reflected in the rapid growth in the number of iron-working guilds, from three in 1300 to fourteen by 1422.

The result was a large influx of money. This, in turn, encouraged the import of manufactured luxury goods. By 1391, shipments from abroad regularly included "ivory, mirrors, paxes, armor, paper..., painted clothes, spectacles, tin images, razors, calamine, treacle, sugar-candy, marking irons, patens..., ox-horns and quantities of wainscot." Imported spices now formed a part of almost all noble and gentry diets, with the amounts consumed depending on the household's wealth. The English government also imported large quantities of raw materials, including copper, for making weapons. Many major landowners tended to focus their efforts on maintaining a single major castle or house rather than the dozens a century before. But these were usually decorated much more luxuriously than before. Major merchants' homes, too, were more lavish than in previous years.

Decline of the Fair System

Towards the end of the 14th century, the importance of fairs began to decline. Larger merchants, especially in London, started to make direct connections with big landowners like the nobility and the church. Instead of the landowner buying from a chartered fair, they would buy directly from the merchant. Meanwhile, the growth of the local English merchant class in the major cities, especially London, gradually pushed out the foreign merchants. The great chartered fairs had largely depended on these foreign merchants. The king's control over trade in the towns, especially the newer towns emerging towards the end of the 15th century that lacked central city government, became weaker. This made chartered status less important as more trade happened from private properties and took place all year round. Nevertheless, the great fairs remained important well into the 15th century. This is shown by their role in exchanging money, regional trade, and providing choice for individual consumers.

Images for kids

-

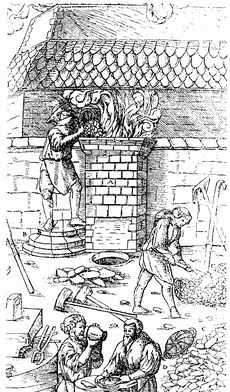

A medieval carving from Rievaulx Abbey showing one of the many new windmills established during the 13th century.

See also

In Spanish: Economía de Inglaterra en la Edad Media para niños

In Spanish: Economía de Inglaterra en la Edad Media para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |