Margery Kempe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Margery Kempe

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | Margery Brunham c. 1373 Bishop's Lynn, England |

| Died | After 1438 |

| Occupation | Christian mystic |

| Language | English |

| Notable works | The Book of Margery Kempe |

Margery Kempe (born around 1373 – died after 1438) was an English Christian mystic. She is famous for having her life story written down in a book called The Book of Margery Kempe. Many people believe this book is the first autobiography (a story of someone's life written by themselves) in the English language. Her book tells about her family life, her many long trips to holy places in Europe and the Holy Land, and her special talks with God. She is honored in the Anglican Communion (a group of Christian churches), but she is not a Catholic saint.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Margery Burnham or Brunham was born around 1373 in a town called Bishop's Lynn (now King's Lynn) in Norfolk, England. Her father, John Brunham, was a successful merchant in Lynn. He was also the mayor of the town and a Member of Parliament, meaning he helped make laws for the country. The first mention of her family, the Brunhams, was in 1320, when her grandfather, Ralph de Brunham, was noted in a town record. Margery's relative, Robert Brunham, who might have been her brother, also became a Member of Parliament for Lynn in 1402 and 1417.

Margery's Life Story

We don't know if Margery Kempe went to school. When she was an adult, a priest would read "religious books" to her in English. This suggests she might not have been able to read them herself. However, she seemed to know many religious texts by heart. She likely learned important prayers like the Lord's Prayer and Ave Maria, the Ten Commandments, and other basic Christian teachings.

Around the age of 20, Margery married John Kempe, who became a town official in 1394. Margery and John had at least 14 children! We know the name of her oldest son was John from a letter found in Gdańsk.

Margery was a faithful Catholic. Like other mystics (people who have a very deep and personal experience of God) in the Middle Ages, she believed God called her to have a very close relationship with Jesus. This happened after she had many visions and special experiences as an adult.

After her first child was born, Margery went through a very difficult time for about eight months. During this time, she said she saw many scary visions of devils and demons. They told her to "give up her faith, her family, and her friends." She also had a vision of Jesus Christ who appeared as a man and asked her, "Daughter, why have you left me, when I never left you?" Margery said she had visits and talks with Jesus, Mary, God, and other religious figures. She also had visions where she felt like she was actually there during the birth and crucifixion of Christ.

These visions and experiences affected her senses. She heard sounds, saw things that weren't there, and even smelled strange odors. She also reported hearing a beautiful heavenly song that made her cry and want to live a very pure life. Margery showed her strong devotion to God in other ways too. She prayed for a pure marriage (without physical intimacy), went to confession often, prayed early and often in church, and wore a rough shirt for religious reasons. She also accepted the negative reactions from people in her community who found her devotion extreme. Margery was also known for crying constantly as she asked Jesus for mercy and forgiveness.

In one of her visions, Jesus told her that he had forgiven her sins. He gave her several instructions: to call him her love, to stop wearing the rough shirt, to stop eating meat, to take Holy Communion every Sunday, and to pray the rosary (a special string of beads used for prayer) only until six o'clock. He also told her to be quiet and talk to him in her thoughts. Jesus promised her that he would help her overcome her problems, give her the ability to answer all scholars, and that he would always be with her and never leave her.

Margery did not join a religious order like a nun. Instead, she lived her life of devotion, prayer, and tears in public. Her visions caused her to cry loudly, sob, and move around in ways that scared and annoyed both priests and regular people. At one point, she was even put in prison by church leaders and town officials.

Finally, in the 1420s, she told her story to someone who wrote it down. This became The Book of Margery Kempe. It describes her visions, her mystical and religious experiences, her struggles with temptation, her travels, and her trials for heresy (beliefs that go against official church teachings). Her book is often seen as the first autobiography written in English.

Margery was accused of heresy many times but was never found guilty. She was proud that she could deny the accusations of Lollardy (a religious movement that challenged the church). People might have accused her because she preached (which women were not allowed to do), or because she wore all white as a married woman (which made her look like a nun). She also seemed to believe she could pray for souls in purgatory (a place where souls go to be purified after death) and know if someone was going to heaven or hell, similar to how saints are believed to pray for others. Margery was also accused of preaching without the Church's permission. Her public speeches were sometimes seen as teaching scripture, which was forbidden for women. During one investigation, she was thought to be possessed by a devil for quoting the Bible. She was reminded of a rule by Paul that women should not preach. Margery was sometimes seen as a bother in the towns where she lived. Her loud crying and strong emotions seemed to suggest a special connection to God that some other people saw as reducing their own faith, or as being too special compared to the relationship between God and the clergy.

Her Spiritual Autobiography

Almost everything we know about Margery Kempe's life comes from her spiritual autobiography, known as The Book. In the early 1430s, even though she couldn't read or write, Margery decided to have her spiritual life recorded. In the beginning of the book, she explains that she hired an Englishman who had lived in Germany to write for her. But he died before the book was finished, and what he had written was hard for others to understand. This first writer might have been her eldest son, John.

Then, she convinced a local priest, who might have been her confessor (someone she confessed her sins to) Robert Springold, to start rewriting the book on July 23, 1436. On April 28, 1438, he began working on an extra part that covered the years 1431–1434.

The story in Margery's Book starts with the difficult birth of her first child. After describing the torment from devils and the appearance of Jesus that followed, Margery tried two home businesses: a brewery and a grain mill. Both were common businesses for women in the Middle Ages. However, both failed quickly. Eventually, Margery turned away from worldly work and gave herself completely to the spiritual calling she felt from her earlier vision.

To live a life dedicated to God, Margery arranged a chaste marriage with her husband in the summer of 1413. This meant they would live together but not have physical intimacy. Although Chapter 15 of The Book of Margery Kempe describes her decision to live a celibate life, Chapter 21 mentions that she became pregnant again. Some people think she gave birth to her last child during one of her pilgrimages. She later said she brought a child with her when she returned to England. It's not clear if the child was conceived before she and her husband started their chaste life, or if they had a momentary lapse after.

Around 1413, Margery visited a female mystic named Julian of Norwich. Julian was an anchoress, a religious woman who lived alone in a small room attached to a church, in Norwich. Margery stayed with Julian for several days. She really wanted Julian to approve of her visions and conversations with God. The book says that Julian approved of Margery's revelations and told her that her religious experiences were real. However, Julian also told Margery to "measure these experiences by how much they honor God and how much they help her fellow Christians." Julian also confirmed that Margery's tears were a physical sign of the Holy Spirit in her soul.

Margery also got confirmation that her gift of tears was real when a friar (a type of religious brother) compared her to a holy woman from another country. In Chapter 62, Margery describes meeting a friar who kept accusing her about her constant tears. This friar admitted he had read about Marie of Oignies and now recognized that Margery's tears also came from true devotion. During this time, Margery's spiritual confessor was Richard Caister, a vicar (a type of priest) at St Stephen's Church, Norwich. He was buried in the church in 1420. Margery prayed at Caister's burial place for a priest to be healed. After the priest was healed, Caister's burial place became a popular spot for pilgrims.

In 1438, the year her book was finished, a "Margueria Kempe" joined the Trinity Guild of Lynn. We don't know for sure if this was the same Margery Kempe, and we don't know when or where she died after this date.

Later Influence of Her Book

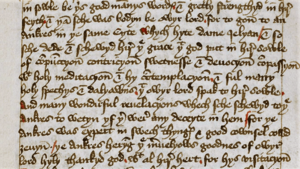

The original handwritten copy of Margery's book was made, probably just before 1450, by someone who signed himself Salthows. This writer was later identified as Richard Salthouse, a monk from Norwich. The manuscript has notes added by four different people. The first page says "Liber Montis Gracie. This boke is of Mountegrace," which means some of the notes were made by monks from the important Carthusian monastery of Mount Grace in Yorkshire. These readers mostly corrected mistakes or made the manuscript clearer. They also wrote comments about the book's meaning and drew some pictures related to Margery's themes. A recipe for medicinal sweets, or digestives, called 'dragges' was added to the last page by a reader from the late 1300s or early 1400s, possibly at the cathedral monastery in Norwich. This shows that many people read her book.

Margery Kempe's book was mostly lost for centuries. People only knew about it from small parts published by Wynkyn de Worde around 1501 and by Henry Pepwell in 1521. However, in 1934, a complete handwritten copy (now called British Library Add MS 61823, the only one left) was found in the private library of the Butler-Bowdon family. Hope Emily Allen then studied it. Since then, it has been printed and translated many times.

Why Margery Kempe is Important

Margery Kempe is important because her book is an autobiography. It gives us the best look into the life of a middle-class woman in the Middle Ages. Margery is unusual compared to other holy women of her time, like Julian of Norwich, because Margery was not a nun.

Even though Margery has sometimes been called "strange" or "crazy," recent studies show that she might not have been as odd as she seems. Her Book is now seen as a carefully put-together spiritual and social commentary. Some have even suggested that it was written as fiction, to explore society in a believable way. The idea that Margery wrote her book as fiction is supported by the fact that she calls herself "this creature" throughout the text, as if she is separate from her work. However, this could also just be her way of showing humility, seeing herself as a humble creature of God.

Her autobiography begins with "the start of her spiritual journey, her recovery from the difficult time after her first child was born." There is no clear proof that Margery could read or write, but she learned a lot from religious texts that were read to her. These included Incendium Amoris by Richard Rolle and possibly works by Walter Hilton. She also had the Revelations of Bridget of Sweden read to her many times. Margery's own pilgrimages were similar to those of this married saint, who also had eight children.

Margery and her Book are important because they show the tension in England during the late Middle Ages. There was a struggle between the official church teachings and new, more public ways of expressing religious beliefs, especially those of the Lollards. Throughout her spiritual life, Margery was questioned by both church and government leaders about whether she followed the official Church teachings. The Bishop of Lincoln and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Arundel, were involved in trials where she was accused of teaching and preaching about the Bible and faith in public, and for wearing white clothes (which was seen as pretending to be a nun while married). In his efforts to stop heresy, Archbishop Arundel had made laws that stopped women from preaching, because a woman preaching was seen as going against church rules.

In the 15th century, a pamphlet was published that showed Margery as an anchoress (a vowed religious woman). This pamphlet removed any ideas or behaviors from her "Book" that might have seemed against church teachings. Because of this, some later scholars believed she was a vowed holy woman like Julian of Norwich. They were surprised when they read the original text of the "Book" and discovered the complex and interesting woman Margery truly was.

Mystical Experiences

During the 1300s, only men, especially ordained priests, were supposed to interpret the Bible and God through writing. Because of this rule, women mystics often showed their experience of God in different ways – through their senses and their bodies – especially in the late Middle Ages. Mystics experienced God directly in three main ways:

- Bodily visions: This meant being aware with one's senses – seeing, hearing, or other senses.

- Ghostly visions: These were spiritual visions and messages given directly to the soul.

- Intellectual enlightenment: This was when a person's mind gained a new understanding of God.

Pilgrimages and Journeys

Margery Kempe was inspired to go on pilgrimages after hearing or reading the English translation of Bridget of Sweden's Revelations. This book encouraged people to buy indulgences at holy sites. Indulgences were like special papers from the Church that pardoned time a person might have to spend in Purgatory after death because of their sins. Margery went on many pilgrimages and bought indulgences for her friends, enemies, souls in Purgatory, and herself.

First Great Pilgrimage (1413-1415)

In 1413, soon after her father died, Margery left her husband to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. During the winter, she spent 13 weeks in Venice. She didn't write much about Venice in her book, even though at that time Venice was "at the height of its medieval splendor, rich in commerce and holy relics." From Venice, Margery traveled to Jerusalem through Ramlah.

Margery's journey from Venice to Jerusalem isn't a huge part of her story. It's thought that she passed through Jaffa, which was the usual port for pilgrims going to Jerusalem. One clear detail she remembered was riding on a donkey when she first saw Jerusalem, probably from Nabi Samwil. She almost fell off the donkey because she was so shocked by the sight. During her pilgrimage, Margery visited places she believed were holy. She stayed in Jerusalem for three weeks and went to Bethlehem, where Christ was born. She visited Mount Zion, where she believed Jesus had washed his disciples' feet. Margery visited the burial places of Jesus, his mother Mary, and the cross itself. Finally, she went to the River Jordan and Mount Quarentyne, where people believed Jesus had fasted for 40 days, and Bethany, where Martha, Mary, and Lazarus had lived.

After visiting the Holy Land, Margery returned to Italy and stayed in Assisi before going to Rome. Like many other English pilgrims in the Middle Ages, Margery stayed at the Hospital of Saint Thomas of Canterbury in Rome. During her stay, she visited many churches, including San Giovanni in Laterano, Santa Maria Maggiore, Santi Apostoli, San Marcello, and St Birgitta's Chapel. She did not leave Rome until Easter 1415. When Margery returned to Norwich, she passed through Middelburg (in what is now the Netherlands).

Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela (1417-1418)

In 1417, Margery set off again on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. She traveled through Bristol, where she stayed at Henbury with Thomas Peverel, the bishop of Worcester. On her way back from Spain, she visited the shrine of the holy blood at Hailes Abbey in Gloucestershire, and then went on to Leicester.

Margery tells about several public questionings during her travels. One happened after she was arrested by the Mayor of Leicester, who threatened her with prison. Margery insisted on her right to have accusations made in English and to defend herself. She was briefly cleared, but then brought to trial again by the Abbot, Dean, and Mayor, and imprisoned for three weeks. After this, Margery continued to York. Here, she had many friends with whom she cried and attended church services. She also faced more accusations, especially of heresy, but she was eventually found innocent by the Archbishop. She returned to Lynn sometime in 1418.

She visited important places and religious figures in England, including Philip Repyngdon (the Bishop of Lincoln), Henry Chichele, and Thomas Arundel (both Archbishops of Canterbury). During the 1420s, Margery lived apart from her husband. However, when he became ill, she returned to Lynn to take care of him. Their son, who lived in Germany, also returned to Lynn with his wife. Sadly, both her son and husband died in 1431.

Pilgrimage to Prussia (1433-1434)

The last part of Margery's book describes a journey she began in April 1433, aiming to travel to Danzig with her daughter-in-law. From Danzig, Margery visited the Holy Blood of Wilsnack relic. She then traveled to Aachen and returned to Lynn through Calais, Canterbury, and London (where she visited Syon Abbey).

Honoring Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe is honored in the Church of England with a special day of remembrance on November 9. She is also honored in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America along with Richard Rolle and Walter Hilton on November 9.

Memorials and Recognition

In 2018, the Mayor of King's Lynn, Nick Daubney, unveiled a bench honoring Margery Kempe in the Saturday Market Place. The bench was designed by a local furniture maker, Toby Winteringham, and paid for by the King's Lynn Civic Society.

There is also a Margery Kempe Society, started in 2018 by Laura Kalas from Swansea University and Laura Varnam from University College, Oxford. Their goal is to support and promote the study and teaching of The Book of Margery Kempe.

In 2020, a statue in honor of Margery Kempe was put up at the entrance of a medieval bridge in Oroso in Northern Spain. This is on the pilgrimage trail she would have followed to Santiago de Compostela.

Plays and Books About Her

Margery Kempe's life and her Book have been featured in several plays and books:

- The Saintliness of Margery Kempe, a play written by John Wulp in 1959, and brought back in 2018.

- Margery Kempe, a novel written by Robert Glück in 1994 and republished in 2020.

- Margery Kempe: The Wife of Lynn's Tale, a play written by Gareth Calway in 2015.

- Skirting Heresy: The Life and Times of Margery Kempe, a book written by academic Elizabeth MacDonald in 2018.

See also

In Spanish: Margery Kempe para niños

In Spanish: Margery Kempe para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |