Julian of Norwich facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Julian of Norwich

|

|

|---|---|

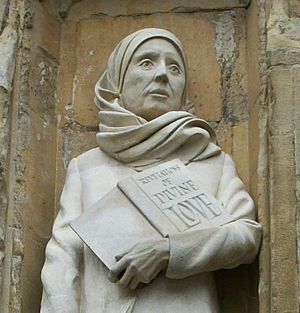

David Holgate's statue of Julian of Norwich, outside Norwich Cathedral, completed in 2000

|

|

| Born | 1343 |

| Died | After 1416 |

| Occupation | Theologian, anchoress, mystic |

|

Notable work

|

Revelations of Divine Love |

| Theological work | |

| Language | Middle English |

Julian of Norwich (born 1343 – died after 1416) was an English mystic and anchoress during the Middle Ages. She is also known as Juliana of Norwich, the Lady Julian, Dame Julian, or Mother Julian. Her most famous writings are called Revelations of Divine Love. These are the earliest known surviving works written in English by a woman. They are also the only surviving writings by an anchoress from England.

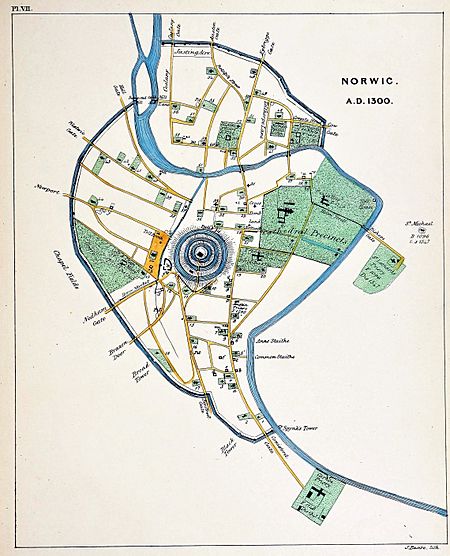

Julian lived in Norwich, an important city in England. Norwich was a busy place for trade and had a strong religious community. During her life, the city faced many challenges. These included the terrible Black Death plague (1348–1350) and the Peasants' Revolt in 1381. There was also a movement called the Lollards that wanted to change the Church.

In 1373, when Julian was 30, she became very ill. She thought she was going to die. During this time, she experienced a series of visions of Jesus' suffering. After she recovered, she wrote down her experiences. She first wrote a shorter version, and then a much longer one years later. This longer version is known today as the Long Text.

Julian lived in seclusion as an anchoress. This meant she stayed in a small room, or cell, attached to St Julian's Church, Norwich. Records show that people left money to an anchoress named Julian in Norwich. The famous mystic Margery Kempe also wrote about visiting Julian for advice.

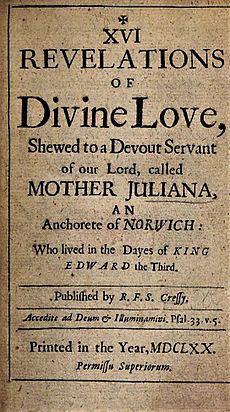

We don't know much about Julian's family or her early life. It's even unclear if Julian was her real name. She preferred to write anonymously and live a quiet life. However, she was very influential during her lifetime. Her writings were carefully kept safe. But the Reformation later stopped them from being printed. The Long Text was first published in 1670. Julian's writings became well-known in 1901 when Grace Harriet Warrack published a new version. Today, Julian is seen as a very important Christian mystic and theologian.

Contents

Life in Medieval Norwich

Julian likely spent her whole life in Norwich, England. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Norwich was the second most important city in England, after London. It was a major center for farming and trade.

During Julian's lifetime, the Black Death arrived in Norwich. This terrible disease might have killed more than half of the city's people. The plague returned many times until 1387. Julian also lived through the Peasants' Revolt in 1381. During this revolt, rebel forces took over Norwich.

Norwich was a very religious city back then. It had a large cathedral, many friaries, churches, and cells for recluses. These religious buildings were a big part of the city's look and the lives of its people.

Julian's Life

How We Know About Julian

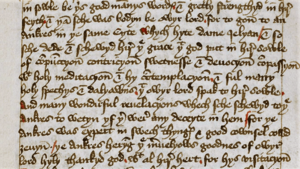

We don't know much about Julian's personal life. She wrote a few things about herself in her book, Revelations of Divine Love. The oldest surviving copy of her book, made in the 1470s, names her as the author.

The earliest records of Julian come from four wills. These wills describe her as an anchoress. People from Norfolk left money to "Julian anakorite" or "Julian, anchoress of the church of St Julian, Conisford." One will from 1404 even mentions "Sarah, living with her," who might have been her helper.

Julian was known as a spiritual guide in her community. She gave advice to people. Around 1414, when Julian was in her seventies, another English mystic named Margery Kempe visited her. Margery Kempe wrote in her book, The Book of Margery Kempe, that she traveled to Norwich to get spiritual advice from Julian. She said God told her to go to "Dame Jelyan" because the anchoress was wise about divine visions and could give good advice.

Her Visions

In Revelations of Divine Love, Julian wrote that she became very sick at age 30. She might have already been an anchoress, or she could have been living at home. Her mother and other people visited her, which usually wasn't allowed for anchoresses. On May 8, 1373, a curate gave her the last rites, preparing her for death. As he held a crucifix above her bed, she started to lose her sight and feel numb. But as she looked at the crucifix, she saw Jesus' figure begin to bleed. Over the next few hours, she had 15 visions of Jesus. She had a 16th vision the next night.

Julian fully recovered from her illness on May 13. Most people agree she wrote about her visions soon after they happened. Her first writings are called the Short Text. Decades later, perhaps in the early 1390s, she began to explore the deeper meaning of her visions. This led to her longer work, The Long Text, which she probably finished around the 1410s or 1420s. Julian's visions were a very important example of a vision by an Englishwoman in 200 years.

Her Personal Life

Julian included very few details about herself in her Short Text, including her gender. She removed these details in her Long Text. Historians are not even sure of her real name. It's thought she took the name Julian from the church where her cell was. But Julian was also a girl's name in the Middle Ages, so it could have been her birth name.

Julian's writings suggest she was born in 1343 or late 1342. She died after 1416. She was six years old when the Black Death reached Norwich. Some people think she might have been educated by the Benedictine nuns at Carrow Abbey, as they had a school for girls. However, there's no proof she was ever a nun there.

Some scholars believe Julian's writings about God's motherly nature suggest she might have been a mother herself. Since plagues were common in the 14th century, she might have lost her own family. Becoming an anchoress would have kept her safe from the plague. However, Julian's writings don't mention the plagues, religious conflicts, or civil unrest that happened in Norwich during her life.

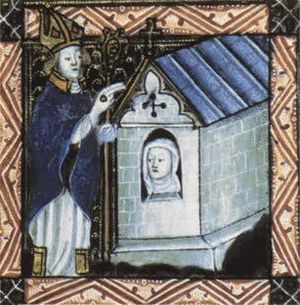

Life as an Anchoress

Julian was an anchoress from at least the 1390s. Living in her cell, she played an important role in her community. She dedicated her life to prayer, supporting the clergy in their work of protecting souls. Her solitary life began after a strict selection process. A special church ceremony would have taken place at St Julian's Church, with the bishop present. During this ceremony, prayers for the dead would have been sung for Julian, as if it were her funeral. She would then be led into her cell, and the door would be sealed. She would stay in her cell for the rest of her life.

Once her life of seclusion began, Julian had to follow strict rules for anchoresses. Two important guides for anchoresses were De institutione inclusarum (written around 1162) and the Ancrene Riwle (written around 1200). The Ancrene Riwle became a guide for all female recluses. It said that anchoresses should live in isolation, in poverty, and under a vow of chastity. The idea of Julian living with her cat comes from the rules in the Ancrene Riwle.

Even though she was an anchoress, Julian was not completely cut off from the world. She received financial support from wealthy people in the community. She also gave prayers and advice to visitors. She was seen as an example of deep holiness.

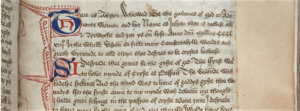

Revelations of Divine Love

Both the Long Text and Short Text of Julian's Revelations of Divine Love describe her visions. Her writings are special because they are the earliest surviving works in English by a woman. They are also the only surviving writings by an English anchoress. The Long Text is much longer, with 86 chapters and about 63,500 words. It is about six times longer than the Short Text.

In 14th-century England, women usually didn't know Latin well. They mostly read and wrote in English. Julian chose to write in her own language, which was common for other medieval writers. She was trying to express deep spiritual ideas in the best way she could.

Julian's writings were mostly unknown until 1670. That's when they were published as XVI Revelations of Divine Love. This first printed book was based on the Long Text. Three handwritten copies of the Long Text still exist today. One is in Paris, and two are in the British Library in London.

A new version of the book was made in 1877. It became even more famous after Grace Harriet Warrack's 1901 edition. This edition used modern language and had a helpful introduction. It introduced many early 20th-century readers to Julian's writings. Historian Henrietta Leyser said Julian was "beloved in the 20th century by theologians and poets alike."

Julian's shorter work, the Short Text, was likely written soon after her visions in May 1373. Like the Long Text, the original handwritten copy was lost. But at least one copy was made by a scribe. This copy was found in 1910 and published in 1911. It is now part of the British Library's collection.

Julian's Ideas About God

From the time these things were first revealed I had often wanted to know what was our Lord's meaning. It was more than fifteen years after that I was answered in my spirit's understanding. "You would know our Lord's meaning in this thing? Know it well. Love was His meaning. Who showed it to you? Love. What did He show you? Love. Why did He show it? For love. Hold on to this and you will know and understand love more and more. But you will not know or learn anything else – ever."

Julian of Norwich is now seen as one of England's most important mystics. For theologian Denys Turner, Julian's main idea in Revelations of Divine Love is about "the problem of sin." Julian said that sin is behovely, which means "necessary," "appropriate," or "fitting."

Julian lived in a difficult time, but her ideas were hopeful. She wrote about God's great goodness and love with joy and compassion. Revelations of Divine Love "contains a message of optimism based on the certainty of being loved by God and of being protected by his Providence."

A special part of Julian's ideas was her comparison of God's love to a mother's love. She believed God is both our mother and our father. She wrote that Jesus is like a mother who is wise, loving, and merciful. Julian believed that Christ is literally the mother, not just like a mother. She said the bond between a mother and child is the closest earthly relationship to the one we can have with Jesus. She used ideas like conceiving, giving birth, and raising children when writing about Jesus.

Julian wrote, "For I saw no wrath except on man's side, and He forgives that in us, for wrath is nothing else but a perversity and an opposition to peace and to love." She believed God sees us as perfect. God waits for us to grow so that evil and sin no longer hold us back. She wrote that "God is nearer to us than our own soul." This idea is repeated in her work: "Jesus answered with these words, saying: 'All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.' ... This was said so tenderly, without blame of any kind toward me or anybody else."

Because she was an anchoress, church leaders at the time might not have challenged her ideas. Also, her writings were not widely known during her lifetime. This might be because she kept them with her in her cell.

Remembering Julian

The Church of England remembers Julian with a special day on May 8. The Episcopal Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the United States also honor her on May 8.

Julian is not officially recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church. However, she is said to have a feast day on May 13. Her words are even quoted in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. In 1997, a priest named Father Giandomenico Mucci suggested Julian could become a Doctor of the Church.

Pope Benedict XVI talked about Julian's life and teachings in 2010. He said: "Julian of Norwich understood the central message for spiritual life: God is love and it is only if one opens oneself to this love, totally and with total trust, and lets it become one's sole guide in life, that all things are transfigured, true peace and true joy found and one is able to radiate it." He ended by quoting her famous words: "'And all will be well,' 'all manner of things shall be well': this is the final message that Julian of Norwich transmits to us."

Julian's Impact Today

Interest in Julian has grown a lot in the 20th and 21st centuries. This is linked to a new interest in Christian contemplation (deep thought and prayer). The Julian Meetings, a group for contemplative prayer, is named after her.

St Julian's Church

Before Julian, there were no hermits or anchoresses in Norwich from 1312 until the 1370s. St Julian's Church, Norwich, located in the south of Norwich city center, still holds regular services. This church, with its round tower, is one of 31 parish churches remaining from the 58 that once existed in Norwich during the Middle Ages. Many of these churches had an anchoress cell.

Julian's cell was not empty after she died. In 1428, Julian(a) Lampett moved into the cell and stayed there until 1478. The cell continued to be used by anchoresses until the 1530s. At that time, monasteries were closed, and the cell was torn down.

By 1845, St Julian's Church was in bad condition. The east wall collapsed that year. After people raised money, the church was restored. It was restored again in the early 20th century. But it was destroyed during the Norwich Blitz in June 1942 when the tower was directly hit. After the war, the church was rebuilt. It now looks much like it did before, but its tower is shorter. A chapel has been built where the old anchoress cell used to be.

Julian in Literature

The Catechism of the Catholic Church uses a quote from Revelations of Divine Love. It explains how God can bring good even from evil. The poet T. S. Eliot included Julian's famous line, "All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well," three times in his poem "Little Gidding" (1943). This poem helped more English-speaking people learn about Julian's writings.

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.—T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Sydney Carter's song "All Shall Be Well" (also called "The Bells of Norwich") uses Julian's words. It was published in 1982. Julian's writings have been translated into many different languages.

Julian in Norwich Today

In 2013, the University of East Anglia honored Julian by naming its new study center the Julian Study Centre. Norwich held its first Julian Week in May 2013. This celebration included concerts, talks, and free events across the city. The goal was to encourage people to learn about Julian and her importance in art, history, and theology.

The Lady Julian Bridge, which crosses the River Wensum near Norwich railway station, is named after her. This swing bridge was built in 2009.

Self-Isolation During the COVID-19 Pandemic

In March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Julian's experiences were mentioned. People around the world were learning about self-isolation. Historian Janina Ramirez said that Julian lived during a time of repeated plagues. She believed Julian was "self-isolating." Other anchoresses understood that by removing themselves from daily life, they could protect themselves. They could also find calm and focus in a confusing world.

Works: Revelations of Divine Love

Manuscripts

Long Text

- Julian of Norwich. "MS Fonds Anglais 40 (previously Regius 8297): Liber Revelacionum Julyane, anachorite norwyche, divisé en quatre-vingt-six chapitres". Anglais 40. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Julian of Norwich. "Sloane MS 2499: Juliana, Mother, Anchorite of Norwich: Revelations to, of Divine Love, 1373". Sloane Manuscripts. British Library.

- Julian of Norwich. "Sloane MS 3705: Visions: Revelations to Mother Juliana in the year 1373 of the love of God in Jesus Christ". Sloane Manuscripts. British Library.

- Westminster Cathedral Treasury MS 4 (W), a late 15th or early 16th century manuscript. It includes extracts from Julian's Long Text, as well as selections from the writings of the English mystic Walter Hilton. The manuscript is on loan to Westminster Abbey's Muniments Room and Library (as of 1997[update]).

Short Text

- "Add MS 37790: A Carthusian anthology of theological works in English (the 'Amherst Manuscript')". Belonged to William Amhurst Tyssen-Amherst, Baron Amherst of Hackney. British Library. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

Selected Editions

- Collins, Henry, ed. (1877). Revelations of Divine Love, Shewed to a Devout Anchoress, by name Mother Julian of Norwich. Mediaeval library of mystical and ascetical works. London: T. Richardson. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002005451084;view=2up;seq=8.

- Cressy, Serenus de. "XVI Revelations of Divine Love, Shewed to a Devout Servant of Our Lord, called Mother Juliana, an Anchorete of Norwich: Who lived in the Dayes of King Edward the Third" (1670). British Library General Reference Collection, ID: Digital Store Cup.403.a.36. London: British Library.

- Warrack, Grace, ed. (1901). Revelations of Divine Love, Recorded by Julian, Anchoress at Norwich, 1373 (1st ed.). London: Methuen and Company. OCLC 560165491. (The second edition (1907) is available online from the Internet Archive.)

- Skinner, John, ed. (1997). Revelation of Love. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-48756-6. https://archive.org/details/revelationoflove00juli.

- Beer, Frances, ed. (1998). Revelations of Divine Love, translated from British Library Additional MS 37790: the Motherhood of God : an excerpt, translated from British Library MS Sloane 2477. Rochester, New York: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-453-6.

- Reynolds, Anna Maria, ed. (2001). Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translations. Florence: SISMEL: Edizioni del Galluzzo. ISBN 978-88-8450-095-3.

- Starr, Mirabai (2013). The Showings of Julian of Norwich: A New Translation. Charlottesville, Virginia: Hampton Roads Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57174-691-7.

- Windeatt, Barry, ed. (2015). Revelations of Divine Love. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811206-8. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Revelations_of_Divine_Love/yoQSBwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

See also

In Spanish: Juliana de Norwich para niños

In Spanish: Juliana de Norwich para niños

- Order of Julian of Norwich

- Visions of Jesus and Mary

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |