Victorian restoration facts for kids

The Victorian restoration was a huge project in England and Wales during the 19th century. It involved extensively fixing up and rebuilding many Church of England churches and cathedrals. This happened during the time when Queen Victoria was queen. It's important to know that this "restoration" was different from how we restore old buildings today.

Many church buildings were in poor condition. Also, people wanted to bring back a more medieval feel to church services, moving away from the very simple style that had been popular. This led to the Gothic Revival, a movement that loved medieval art and architecture. The Church of England supported these changes. They hoped it would encourage more people to attend church again.

The main idea was to make churches look like they did during the "Decorated style" of architecture. This style was popular between 1260 and 1360. Famous architects like George Gilbert Scott and Ewan Christian eagerly took on these restoration jobs. It's thought that about 80% of all Church of England churches were changed in some way. Some had small updates, while others were completely torn down and rebuilt.

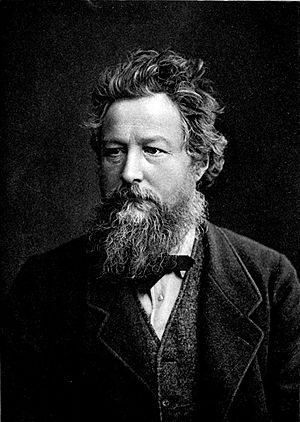

However, not everyone agreed with these big changes. Important people like John Ruskin and William Morris were against such large-scale restoration. Their efforts eventually led to groups like the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings being formed. Looking back, many people don't think the Victorian restoration was a good thing. But it did help save some churches that might have fallen apart. It also led to the discovery of some old features that had been hidden for a long time.

Contents

Why Churches Were Restored

Several things came together to cause the wave of Victorian restoration.

For about 250 years, after the English Reformation, churches and cathedrals in England didn't get much building work. They only had small repairs to keep them usable. This meant many church buildings became neglected and fell into disrepair. A clear example of this problem happened in 1861. The spire of Chichester Cathedral suddenly collapsed!

Also, since the mid-17th century, a movement called the Puritan reforms had made religious services very plain. They focused on preaching and removed most decoration and emotion from churches. This was to show they were different from what they saw as the excessive style of Catholicism. But by the late 1700s, people became more interested in the Gothic Revival and medievalism. They wanted more interesting religious services. Church leaders saw the popularity of the Gothic Revival as a way to get more people back to church. They hoped it would help the Church regain its power and influence. So, they pushed for huge restoration projects.

A third reason was the Industrial Revolution. Many people moved to cities, but these cities didn't have enough churches for everyone. For example, Stockport had almost 34,000 people, but only enough church seats for 2,500. The rise of other Christian groups, like Methodism, also showed this shortage. To help, the government gave £1.5 million between 1818 and 1824 to build new churches. These "Commissioners' churches" were often built cheaply and didn't look very good. This made people want better church designs.

Similar movements happened in other parts of Europe, especially in northern Europe. The French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was very involved in this in France.

Who Led the Changes?

The Cambridge Camden Society

One of the main groups pushing for church restoration was the Cambridge Camden Society (CCS). It was started in 1839 by two students from Cambridge, John Mason Neale and Benjamin Webb. They shared an interest in Gothic church design. The group quickly grew, from 8 members to 180 in just one year!

At first, the CCS just studied medieval church features. But soon, in their journal The Ecclesiologist, they started saying that only one style was "correct" for a church. This was the "Decorated" style, used around the year 1300. This idea, called Ecclesiology, became very popular. It fit well with the growing interest in medievalism and the Gothic Revival.

The CCS was very firm about this one "correct" style. This helped people who weren't sure what "good" architecture looked like anymore. The CCS said there were two ways to restore a church. As Kenneth Clark explained, you could either fix each part in its original style, or make the whole church match the "best and purest style" found in it. The CCS strongly suggested the second option. Since almost every medieval church had at least a small piece of Decorated style, like a porch or a window, they would "restore" the whole church to match it. If the oldest parts were from a later time, they would completely rebuild the church in the "correct" style.

The Ecclesiologist said that "to restore" meant "to bring back the original look... lost by decay, accident or bad changes." However, they later admitted that this kind of "restoration" might create an ideal church that never actually existed before.

The Oxford Movement

Church restorations were also greatly influenced by the Oxford Movement. This group believed that the most important part of church services should be the sacrament of the Eucharist (Communion), not just preaching. This meant moving the focus from the pulpit to the altar. Because of this, pulpits were moved to the side of the church. Old box pews were replaced with open pews, and a central aisle was created for a better view of the altar. Galleries were also removed. Another change was that a larger chancel (the area around the altar) was needed for the new rituals.

What Was Done?

Because of the Cambridge Camden Society's ideas about the "Decorated Gothic" style and the Oxford Movement's ideas about worship, a lot of "restoration" work began. The numbers show how big this was. In the 40 years leading up to 1875, 3,765 new and rebuilt churches were officially opened. The busiest time was the 1860s, with over 1,000 churches opened. More than 7,000 parish churches in England and Wales, which is almost 80% of all of them, were restored in some way between 1840 and 1875. The number of professional architects grew by 150% between 1851 and 1871. Experienced architects often gave smaller restoration jobs to newer architects, as it was good practice.

Early restorers didn't always care much about keeping original materials like old carvings or woodwork. The new "look" was most important. So, many good old pieces were thrown away and replaced with new ones in the chosen style. As the century went on, architects generally took more care. This was partly because more people started speaking out against the changes.

For example, in 1870–71, the Church of St Peter, Great Berkhamsted, was restored by William Butterfield. He also designed famous churches like All Saints, Margaret Street in London. Butterfield's restoration removed some original features, including paintings on the pillars. Major changes included raising the roof and floor of the chancel. He also raised the roof of the south transept to its original height. The vestry was removed, and the south porch was made part of the south aisle. The nave floor was replaced, new oak benches were installed, and an old gallery was removed. Butterfield also put clear windows in the upper part of the church, letting in more light. Outside, he removed old plaster and covered the church walls with new flint stone.

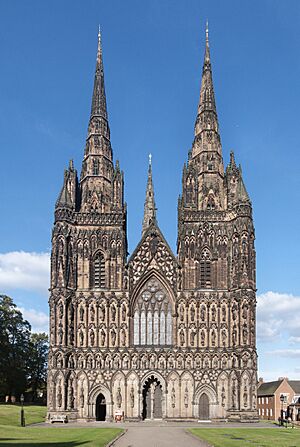

At Lichfield Cathedral, the 1700s had been a time of decay. The 15th-century library was pulled down, and most statues on the west front were removed. The stonework was covered with cement. After some early 19th-century work by James Wyatt, the fancy west front (pictured above) was restored by Sir George Gilbert Scott. It now has many carved figures of kings, queens, and saints. These were made from original materials if possible, or new copies if not. Scott also used medieval stonework from Wyatt's old choir screen to create seats for the clergy. A new metal screen and a colorful tile floor were also added, inspired by medieval tiles found in the choir's foundations.

Key Architects

Famous architects like George Gilbert Scott, Ewan Christian, William Butterfield, and George Edmund Street became very keen "restorers." This wave of restoration spread across the country. By 1875, about 80% of all churches in England had been changed in some way.

In 1850, Scott wrote a book called A plea for the faithful restoration of our Ancient Churches. In it, he said it was good to keep signs of how buildings had grown and changed over time. However, in his actual work, he often didn't follow this rule. He usually removed all later changes and rebuilt the church in one early style. Sometimes, he did this based on just one small old feature that remained.

Who Was Against It?

Not everyone supported the restorations. The Reverend John Louis Petit was a strong opponent from his first book, Remarks on Church Architecture (1841), until he died in 1868. The Archaeological Society was started in 1845 by historians who wanted more people to appreciate old buildings. Although John Ruskin generally liked new buildings in an early Gothic style, he wrote in 1849 that it was impossible "to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture." The Society of Antiquaries of London said in 1855 that "no restoration should ever be attempted, otherwise than... in the sense of preservation from further injuries."

A later strong opponent was William Morris. He fought against the planned restoration of St John the Baptist Church, Inglesham, in the 1880s. He started the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1877. This happened when he heard about the planned restoration of Tewkesbury Abbey by Scott. It took some time for SPAB's ideas to gain support. But their policy of "Protection in place of Restoration" eventually became widely accepted and is still followed today. Morris also wrote in 1877:

But of late years a great uprising of ecclesiastical zeal, coinciding with a great increase of study, and consequently of knowledge of medieval architecture has driven people into spending their money on these buildings, not merely with the purpose of repairing them, of keeping them safe, clean, and wind and water-tight, but also of "restoring" them to some ideal state of perfection; sweeping away if possible all signs of what has befallen them at least since the Reformation, and often since dates much earlier.

Even though he was against restorations, Morris's company made a lot of money providing stained glass for many restoration projects. It's been noted that his criticism only started after his company was well-established as a supplier for these projects. But after 1880, following SPAB's rules, his company stopped taking stained glass jobs for historic church buildings.

Other groups also opposed the restorations. Some Protestants believed that "fancy carved work, decorative painting, colorful tiles, and stained glass were foolish things that lead the heart astray." Others were worried about the cost. They argued: "For the cost of one stone church with a fancy roof, two could be built in brick with plain ceilings. And who could say that worship in the plainer building would be less sincere?"

Not all Catholics were in favor either. Later in his life, Cardinal Wiseman made it clear he preferred Renaissance art. This was expected, as his religious order had Italian origins.

Looking Back

From today's point of view, the Victorian restoration process is often seen negatively. Words like "ruthless," "insensitive," and "heavy-handed" are commonly used to describe the work done.

In his book The Gothic Revival, Kenneth Clark wrote that "The real reason the Gothic Revival had been neglected is that it produced so little on which our eyes can rest without pain." Clark also thought that the Decorated Gothic style was the hardest of the three main Gothic styles to work with. The other two, Early English and Perpendicular, were much easier for builders. Clark pointed out that Decorated was difficult, especially because of its complex window designs.

However, not all restoration work was bad. A positive side effect of some restorations was the rediscovery of old features that had been hidden for a long time. For example, Anglo-Saxon carvings were found built into later Norman foundations. Also, old wall-paintings that had been covered with whitewash were rediscovered, like at St Albans Cathedral. It's also true that if these churches hadn't been restored, many might have fallen apart completely.

See also

In Spanish: Restauración victoriana para niños

In Spanish: Restauración victoriana para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |