History of citizenship facts for kids

The history of citizenship looks at how the connection between a person and their country has changed over time. This connection is called citizenship. Many people think citizenship started in Western civilization, not in Eastern cultures. In ancient times, citizenship was often simpler than it is today, but some experts disagree with this idea.

Many thinkers believe citizenship first appeared in the early city-states of ancient Greece. This might have happened because people feared slavery. Others think citizenship is a more recent idea, only a few hundred years old. In Roman times, citizenship became more about laws. People had less political involvement than in Greece, but more people could become citizens. During the Middle Ages in Europe, citizenship was mostly linked to business and city life. It then became about being a member of a nation-state.

Today, in modern democracies, citizenship has two main ideas. One is the liberal-individualist view. This idea focuses on what people need and what they are allowed to have, like legal protections. It sees citizens as mostly passive. The other is the civic-republican view. This idea stresses that citizens should actively take part in politics. It sees citizenship as an active relationship with special rights and duties.

Even though citizenship has changed a lot, some things have stayed the same. Citizenship connects people from different backgrounds, going beyond just family ties. It describes the link between a person and a larger political group, like a city-state or a nation. It often involves military service or the expectation of it. Citizens usually have some way to participate in politics. This can be as simple as voting or as active as serving in government. Throughout history, citizenship has often been seen as an ideal state, linked to freedom and important rights. It has also often meant that non-citizens were excluded from certain rights and privileges.

Contents

Understanding Citizenship Over Time

Citizenship means being a member of a political society or group. But it's actually quite hard to define. Even thinkers like Aristotle knew there was no single definition. Modern experts agree that the history of citizenship is complex. It's hard to understand citizenship without also thinking about nationalism, civil society, and democracy.

Citizenship is different in different cultures. How it's seen also depends on who is looking at it. For example, someone from an upper class background might see citizenship differently than someone from the lower class. Citizenship has always changed within each society. Some believe it only "really worked" at certain times, like when Solon made reforms in ancient Athens.

Some historians see citizenship as a long, steady journey through Western civilization, starting in Ancient Greece and continuing to today. Others question this idea. They think it's too simple and might lead to wrong conclusions. They believe we should understand citizenship by looking at it within its own time and place. The growth of citizenship is also linked to the development of law.

Comparing Ancient and Modern Citizenship

Here's how citizenship has changed from ancient times to today, according to Peter Zarrow:

| Ancient | Modern |

|---|---|

| Very limited | Almost everyone can be a citizen |

| Included legal and community rules | Most societies offer legal protection and social services |

| Rights matched social status | Rights are not tied to social status |

| Citizens met face-to-face | Anonymous members of large groups |

| Public life was valued for its own sake |

Citizenship in Ancient Times

Early Ideas from Jewish People

Some experts believe the idea of citizenship began with the ancient Israelites. They saw themselves as a special and unique people, different from the Egyptians or Babylonians. They had a written history, a common language, and believed in one God, which is sometimes called ethical monotheism. While most groups were tied to a specific place, the Jewish people kept their identity even when they were moved to different lands, like when they were slaves in ancient Egypt or Babylon.

The Jewish Covenant was a promise not just with a few leaders, but with the whole nation of Israel, including men, women, and children, and their God, Yahweh. Like other tribal groups, Jews didn't call themselves "citizens." But they had a very strong bond with their own group. People from other ethnic groups were seen as "outsiders." This is different from modern citizenship, which aims to include people of different races and backgrounds under one nation.

The Israelites were often against having kings. The Bible shows that kings could take men for the army, women for housework, and land and food for themselves. But the Bible also limited the king's power. For example, a king couldn't have too many wives, horses, or too much money. He was mainly supposed to follow the law. This idea of limited government, where the ruler's power is not absolute, is an important part of what we now call "liberal democracy."

Ancient Greece: Birth of Citizenship

Citizenship in the Polis

Many agree that true citizenship began in ancient Greece. It appeared in the Greek city-states, called poleis, around the 8th century BCE. These cities were found around the Aegean Sea, the Black Sea, and the Mediterranean. The modern idea of citizenship by choice (like naturalization) versus citizenship by birth (like birthright) can be traced back to ancient Greece. Some thinkers, like J.G.A. Pocock, say that the ancient Athenians and Romans first developed the ideal of citizenship.

For the ancient Greeks, citizenship was a strong bond between a person and their city-state. Before this, people were usually connected to a tribe or extended family. Citizenship added a new layer: a bond with the state that wasn't based on family. Historian Geoffrey Hosking suggests that citizenship in ancient Greece grew from a deep appreciation for freedom. He explained that any Greek farmer could fall into debt and become a slave. So, Greeks fought to avoid being enslaved and set up their political systems to stay free.

The Greek idea of the polis, where citizenship and the rule of law were important, helped them greatly in their wars with Persia.

The polis was based on nomos, the rule of law. This meant no person, no matter how powerful, was above the law. Everyone followed the same rules. Any leader who put himself above the law was called a tyrannos—a tyrant. It was also based on citizenship—the idea that every person born into the community shared in power and responsibility. This idea that we should live as citizens under the rule of law was started by the Greeks. It was their greatest gift to mankind. It meant Greeks were willing to live, fight, and die for their poleis...

Greeks benefited from having slaves. Slaves did the hard work, which gave slaveowners free time to take part in public life. Even though Greek city-states often fought, they shared many things. These included the Mediterranean trade, family ties, the Greek language, and a dislike for non-Greek-speaking people. They also believed in the oracle at Delphi and later had the Olympic Games. Some believed that regular wars were needed to keep citizenship strong, as seized goods and slaves made the city-state rich.

A key part of polis citizenship was that it was exclusive. Polis meant both the political meeting and the whole society. People accepted that not everyone was equal. Citizens had a higher status than non-citizens, like women, slaves, or barbarians. For example, women were thought to be unable to take part in politics, though Plato disagreed. Citizenship could be based on wealth (how much tax you paid), political involvement, or if both your parents were citizens.

The first type of citizenship was based on how people lived in ancient Greek times, in small communities. Citizenship was not separate from a person's daily life. The duties of citizenship were deeply connected to everyday life in the polis.

The Greek idea of citizenship might have come from military needs. A key military formation, the phalanx, required soldiers to stand shoulder-to-shoulder in a "compact mass." Each soldier's shield protected the soldier to his left. If one soldier failed, the whole group could fall apart. This technique needed many soldiers, sometimes most adult men in a city-state. They bought their own weapons. The idea was that if each man had a say in whether the city-state fought, and if each man followed the group's will, then loyalty on the battlefield was much stronger. So, political participation was linked to military success.

Greek city-states were also the first to separate judicial (court) functions from legislative (law-making) functions. Citizens were chosen to be jurors and were often paid a small amount. Greeks usually disliked tyrannical governments. In a tyranny, there was no citizenship because political life was only for the ruler's benefit.

Spartan Citizenship

Some thinkers believe that ancient Sparta, not Athens, was where citizenship began. Spartan citizenship was based on the idea of equality among a ruling military group called Spartiates. These were "full Spartan citizens"—men who finished tough military training. At age 30, they received land, but they had to keep paying dues for food and drink to stay citizens. In Spartan warfare, courage and loyalty were very important.

Each Spartan citizen owned enough public land to feed a family. Spartan citizens relied on captured slaves called helots to do the farming and daily work. This allowed Spartan men to focus on military training and citizenship. Manual labor was seen as not fitting for citizens. Citizens ate meals together in a "communal mess." They were "frugally fed, fiercely disciplined, and kept in constant training," according to Hosking. Young men served in the military. As they got older, it was seen as good to take part in government. Participation was required; if you didn't show up, you could lose your citizenship.

However, the philosopher Aristotle thought the Spartan model of citizenship was "artificial and strained." While Spartans learned music and poetry, serious study was not encouraged. Spartan women had more independence and rights than Athenian women. They could own property and, at one point, owned up to 40% of the land. Their main job was to have strong, healthy babies.

Athenian Citizenship

In his book Constitution of the Athenians (350 BCE), Aristotle suggested that ancient Greeks believed being a citizen was natural. It was an elitist idea, meaning only a few had this status. Small communities generally agreed on how people should act. Geoffrey Hosking described how Athens might have moved towards participatory democracy:

If you have many soldiers with modest means, and you want them to fight enthusiastically, then you need a political and economic system that doesn't let too many fall into debt. Debt eventually means slavery, and slaves cannot fight in the army. And it needs a political system that gives them a say in matters that affect their lives.

Because of this, the old aristocratic constitution in Athens slowly changed. It became more open to more people. In the early 6th century BCE, the reformer Solon replaced the strict Draconian constitution with the Solonian Constitution. Solon canceled all land debts. He allowed free Athenian men to take part in the assembly, called the ecclesia. He also encouraged foreign craftsmen, especially potters, to move to Athens and offered them citizenship. Solon expected the wealthy Athenians to still run things, but citizens now had a "political voice in the Assembly."

Later reformers pushed Athens even more towards direct democracy. In 508 BCE, Cleisthenes reorganized Athenian society. He changed groups based on family (like phratries) into larger, mixed groups. These new groups combined people from different areas: coasts, cities, and plains. Cleisthenes removed the old tribes, making them disappear. This meant farmers, sailors, and shepherds came together in the same political unit. This lessened the importance of family ties for citizenship. So, Athenian citizenship went beyond family, race, or tribal membership. It moved towards the idea of a diverse state built on democratic principles.

Cleisthenes brought democracy to the common people in a way Solon didn't. ... Cleisthenes gave these same people the chance to take part in a political system where all citizens—rich and poor—were equal in theory. No matter where they lived in Attica, they could take part in some form of state administration.

Athenian citizenship was based on the duties citizens had to the community, rather than just rights. This wasn't a problem because people felt a strong connection to their polis. Their personal future and the future of the community were closely linked. Citizens also saw their duties as a chance to be good and honorable. The citizens were "their own masters." The people were sovereign; no power was outside of them. In Athens, citizens were both rulers and ruled. Important political and court jobs were rotated to allow more people to participate and prevent corruption. All citizens had the right to speak and vote in the assembly.

... what makes the citizen the highest order of being is his ability to rule. This means that ruling over someone equal is only possible if that equal also rules over you. So the citizen rules and is ruled; citizens join together to make decisions where each person respects the authority of the others, and all obey the decisions (now called "laws") they have made.

Athenians believed in "laws that should govern everybody," meaning equality under the law, or isonomia. Citizens had certain rights and duties. Rights included speaking and voting in the assembly, holding public office, serving as jurors, being protected by law, owning land, and taking part in public worship. Duties included obeying the law and serving in the armed forces. This could be "costly" because they had to buy war equipment or risk their lives.

This balance of participation, duties, and rights was the core of citizenship. It also included the feeling that there was a common interest that everyone had to follow.

Hosking noted that citizenship was "relatively narrowly distributed." It excluded all women, all minors, all slaves, all immigrants, and most colonists. Many historians saw this exclusiveness as a weakness. However, Hosking pointed out that there were about 50,000 Athenian citizens, and only about a tenth of them ever attended an assembly at one time. He argued that if citizenship had been spread more widely, it might have hurt their unity. Pocock agreed, saying citizenship needed some distance from daily chores. Greek men solved this by having women and slaves do the daily work, freeing them to participate in the assembly.

Plato on Citizenship

The philosopher Plato imagined a warrior class, similar to Sparta's idea. These warriors would not farm, do business, or handicrafts. Their main duty was to constantly prepare for war. Like the Spartans, Plato's ideal community had citizens who ate common meals to build strong bonds. Citizenship status, in Plato's ideal view, was inherited. There were penalties for not voting. A key part of citizenship was obeying the law and having self-control.

Aristotle on Citizenship

Aristotle, writing after Plato, did not like Sparta's community-focused approach. He felt Sparta's land system and communal meals created a society where rich and poor were too far apart. He saw differences in citizenship based on age: young people were "underdeveloped" citizens, and the elderly were "superannuated" citizens. He also noted it was hard to classify some people, like resident foreigners who could use the courts, or citizens who had lost their rights.

Still, Aristotle believed citizenship was a legally guaranteed role in creating and running government. He saw it as a commanding role in society, with citizens ruling over non-citizens. But there couldn't be a permanent barrier between rulers and ruled. Aristotle's idea of citizenship depended on a clear separation of public and private life. To be truly human, one had to be an active citizen in the community:

To take no part in the running of the community's affairs is to be either a beast or a god!

In Aristotle's view, "man is a political animal." Isolated men were not truly free. A "beast" was animal-like, without self-control, and couldn't work with others, so it couldn't be a citizen. A god was too powerful and immortal to need help from others. Aristotle believed citizenship was generally possible only in a small city-state, where people knew "one another's characters" and could participate directly in public affairs. Citizens had the freedom to join political discussions if they wanted. Citizenship was not just a way to be free, but was freedom itself. It meant actively sharing in civic life, where all men rule and are ruled in turn. Citizens were those who shared in law-making and judicial roles. What citizens did should benefit everyone, not just a part of society. Unlike Plato, Aristotle believed women could not be citizens because it didn't suit their nature.

Roman Citizenship: Law and Expansion

How Rome Differed from Greece

Roman citizenship was similar to the Greek model but had important differences. Geoffrey Hosking argued that Greek ideas like equality under the law, civic participation, and limiting power were carried into the Roman world. But unlike Greek city-states, which enslaved captured people, Rome offered relatively good terms to its captives. They could even gain a "second category of Roman citizenship." Conquered people couldn't vote in the Roman assembly but had full legal protection. They could make business deals and marry Roman citizens. They mixed with Romans in a culture called Romanitas, which included ceremonies, public baths, and games.

The Roman idea of citizenship also considered that citizens could act upon material things, like buying and selling property. This added a new level of complexity to citizenship, as commerce often needed rules.

The person was defined and represented through his actions upon things; over time, the term property came to mean, first, the defining characteristic of a human or other being; second, the relation which a person had with a thing; and third, the thing defined as the possession of some person.

Social Classes in Rome

Another difference from the Greek model was that the Roman government often saw conflicts between the upper-class patricians and the lower-class working groups, called the plebeians. This was a "tense tug-of-war." The plebeians, unhappy with their situation, threatened to create their own city. Through talks around 494 BCE, they won the right to have their interests represented in government by officers called tribunes. The Roman Republic tried to balance the upper and lower classes. For upper-class men, citizenship meant actively influencing public life. For lower-class men, it was about respecting their "private rights."

Citizenship as a Legal Relationship

Pocock explained that a citizen became someone "free to act by law, free to ask and expect the law's protection." An example is Saint Paul demanding fair treatment after his arrest by saying he was a Roman citizen. Many thinkers, including Pocock, suggest that the Roman idea of citizenship focused more on it being a legal relationship with the state. It was seen as the "legal and political shield of a free person." Citizenship also had a "cosmopolitan character," meaning it applied to many different people.

Citizenship meant having rights to possessions, protections, and expectations. These were available in many ways and degrees. Citizens could "sue and be sued in certain courts." The law itself was a bond uniting people. Citizenship came to mean "membership in a community of shared or common law." According to Pocock, Rome's focus on law changed citizenship. It became more impersonal, universal, and had different levels and uses. It included many types of citizenship, sometimes for a city, sometimes for the whole empire.

Law continued to grow under the Romans. They developed law into a science called jurisprudence. Law helped protect citizens:

The priests agreed to have basic laws written on twelve stone tablets and displayed in the forum for everyone to see ... Writing these things on stone tablets was very important. First, it meant the law was stable and permanent; it was the same for everyone and couldn't be changed by powerful people. Second, it was publicly known; it wasn't secret; anyone could look it up at any time.

Law experts found ways to adapt fixed laws and to make common law (jus gentium) work with natural law (ius naturale). Property was protected by law, which protected individuals from the state's power. Also, unlike Greece, where laws were mostly made in the assembly, Roman law was often decided in other places, like court rulings or sovereign decrees. This meant the assembly's power became less important.

Expanding Citizenship in Rome

In the Roman Empire, polis citizenship grew from small communities to the entire empire. In the early Roman Republic, citizenship was highly valued and not given to many. Romans realized that giving citizenship to people across the empire made their rule more legitimate. Over centuries, citizenship became less about political involvement and more about legal protection and the rule of law.

Roman citizenship was more complex than the Athenian idea. It usually didn't involve political participation. There were many different roles for citizens, which sometimes led to "contradictory obligations." Roman citizenship wasn't just "citizen" or "non-citizen." There were more levels and relationships. Women were respected more and had a secure status as "subsidiary citizens."

These citizenship rules generally helped build loyalty throughout the diverse empire. The Roman statesman Cicero encouraged political participation. But he also saw that too much civic activism could be dangerous. David Burchell argued that in Cicero's time, too many citizens wanted to "enhance their dignity." This led to disagreements. Extreme inequality in land wealth led to a decline in the citizen-soldier system. This was one reason for the Republic's fall and the rise of dictators. The Roman Empire slowly expanded who was considered a "citizen." But the economic power of people declined, and fewer men wanted to serve in the military. Giving citizenship to many non-Romans, some say, made its meaning less special.

Fall of Rome

When the Western Roman empire fell in 476 AD, the western part was attacked. The eastern empire, with its capital at Constantinople, continued. Some thinkers believe that because of this, western Europe developed two sources of authority: religious and secular. This separation of church and state was a "major step" towards modern citizenship. In the eastern empire, religious and secular power were combined in the emperor. The eastern Roman emperor Justinian (527-565) believed citizenship meant living with honor, not causing harm, and giving "each their due."

Early Modern Ideas of Citizenship

Feudalism and New Beginnings

In the feudal system, there were two-way relationships between lords and vassals. Vassals promised loyalty and support, and lords promised protection. Feudalism was based on controlling land. A person's loyalty was not to a law or a nation, but to another person, like a knight, lord, or king. Some believe feudalism's system of mutual duties led to the idea of the individual and the citizen.

The Magna Carta, though a "feudal document," marked a change. It wasn't a personal bond between nobles and the king. Instead, it was more like a contract written in formal language, describing how different groups should act. Magna Carta promised that the liberty, security, and freedom of individuals were "inviolable." Slowly, the personal ties between vassals and lords were replaced by more formal, impersonal relationships.

Early medieval communes sometimes had very active citizenship. Intense religious activity led to conflict and violence. Because of this, Europeans learned to value the "dutiful passive citizen" more than the "self-directed religious zealot."

Renaissance Italy: Cities and Humanism

In the 14th century, Italy was more urban than the rest of Europe. Cities like Milan, Rome, Genoa, Florence, and Venice had large populations. Trade with the Middle East and new industries like wool brought more wealth. This led to more education and study of the liberal arts, especially among young people in cities. A philosophy called Studia Humanitatis, later known as humanism, emerged. It shifted focus from the church to secular life. Thinkers studied ancient Rome and ancient Greece, including their ideas about citizenship and politics. Competition among cities also encouraged new thinking.

Florence was the city that most resembled a true Republic. Most other Italian cities were "complex oligarchies" ruled by rich citizens called patricians. Florence's leaders believed that civic education was vital to protect the Republic. They wanted citizens and leaders to handle future crises. Politics, once seen as unspiritual, became a "worthy and honorable vocation." Most people, from rich merchants to workers, were expected to participate in public life. A new sense of citizenship began to grow, based on the "often turbulent internal political life in the towns." There was competition among guilds and much political debate.

Early European Towns and Nation-States

During the Renaissance and Europe's growth, medieval scholar Walter Ullmann suggested that people changed from being subjects of a monarch to being citizens of a city, and later a nation. A city's key features were its own laws, courts, and independent administration. Being a citizen often meant following the city's law and helping choose officials. Cities were also for defense. Citizens were people who could afford weapons and train themselves. One idea is that the need for individual citizen-soldiers to provide their own equipment explains why Western cities developed citizenship, while Eastern ones generally did not. City dwellers who fought alongside nobles no longer wanted a lower social status. They demanded a greater role as citizens. Besides city administration, joining guilds was an indirect form of citizenship. Guilds helped their members financially and had much political influence in growing towns.

During the European Middle Ages, citizenship was usually linked to cities. Nobility had higher privileges than commoners. The rise of citizenship was connected to the rise of republicanism. If a republic belonged to its citizens, kings had less power. In the new nation-states, the nation's land was its territory, and citizenship was an ideal. Citizenship increasingly connected a person to the state based on abstract ideas like rights and duties, rather than to a lord or count.

Citizenship was increasingly seen as something you got at birth. But nations often welcomed foreigners with important skills. These new people could become citizens through a process called naturalization. More naturalization cases helped people see citizenship as a choice. Citizens were people who freely chose loyalty to the state, accepted the legal status of citizenship with its rights and duties, obeyed its laws, and were loyal to the state.

Great Britain: Rights and Parliament

The early modern period in Great Britain saw big changes in how individuals fit into society. The power of Parliament grew compared to the monarch.

The English Reformation in the 16th century brought political, constitutional, social, and cultural changes. It also shaped England's national identity and slowly changed people's religious beliefs, establishing the Church of England.

In the 17th century, there was new interest in the Magna Carta. English judge Sir Edward Coke brought back the idea of rights based on citizenship. He argued that Englishmen had always had these rights. Laws like the Petition of Right (1628) and the Habeas Corpus Act (1679) set certain freedoms for subjects. The idea of political parties began with groups discussing political representation during the Putney Debates (1647). After the English Civil Wars (1642–1651) and the Glorious Revolution (1688), the Bill of Rights was passed in 1689. This law set out rights and freedoms. It required regular elections, allowed freedom of speech in Parliament, and limited the monarch's power. This meant that, unlike much of Europe, royal absolutism (absolute rule by a king) would not happen in Britain.

Across Europe, the Age of Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries spread new ideas about liberty, reason, and politics.

The American Revolution: New Freedoms

British colonists in America had grown up with democratic local governments, where wealthy men participated. But after the French and Indian War, colonists disliked new taxes from Britain. They were especially angry about not having representatives in the British Parliament. The cry "no taxation without representation" became common. The fight between colonists and British troops was a time when citizenship "worked."

American and later French declarations of rights helped link basic rights to popular sovereignty. This meant governments got their power from the consent of the governed. The people who wrote the United States Constitution chose representative democracy instead of direct democracy to handle a growing country. This changed citizenship, as citizens now chose others to represent them. The revolution created a sense of "broadening inclusion."

The Constitution set up a federal government and state governments. But it didn't define citizenship. The Bill of Rights protected individual rights from the federal government. The term citizen wasn't defined until the Fourteenth Amendment was added in 1868. It said U.S. citizenship included "All persons born or naturalized in the United States." The American Revolution showed that Enlightenment ideas about government could actually be put into practice.

The French Revolution: Loyalty to the Nation

The French Revolution brought huge changes and is seen as a major event in modern politics. Before the revolution, under the Ancien Regime, people were loyal to the person above them in a hierarchy. For example, serfs were loyal to local lords, who were loyal to nobles, who were loyal to the king, who was loyal to God. Clergy and nobles had special privileges, like better treatment in courts and no taxes. This meant peasants paid most of the national expenses. Powerful groups kept a small elite in power and kept ordinary people from political decisions.

These arrangements changed a lot during and after the French Revolution. Louis XVI mismanaged money and was blamed for inaction during a famine. The French people saw the king's interests as against the nation's. Early in the uprising, aristocratic privileges were abolished on August 4, 1789. A noble, Vicomte de Noailles, announced he would give up all special privileges and be known only as the "Citizen of Noailles." Other nobles joined him, dismantling the old system.

Later that month, the Assembly's Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen linked rights with citizenship. It stated that human rights were "natural, inalienable, and sacred," and that all men were "born free and equal." The goal of government was to protect these rights. However, the document didn't mention women's rights. Activist Olympe de Gouge later argued that women were born with equal rights. People began to feel a new loyalty to the nation as a whole, as citizens. The idea of popular sovereignty, first suggested by Rousseau, took hold, along with strong feelings of nationalism. Louis XVI and his wife were executed.

Citizenship became more inclusive and democratic, linked to rights and national membership. The king's government was replaced with an administrative hierarchy at all levels, from national to local. Power flowed both up and down. Loyalty became a key part of citizenship. One expert suggested that in the French Revolution, two different ideas of citizenship merged: (1) the abstract idea of citizenship as equality before the law, and (2) the idea of citizenship as a special status for rule-makers. The British thinker T. H. Marshall saw "serious growth" of civil rights in the 18th century. These civil rights included free speech, the right to a fair trial, and equal access to the legal system. Marshall saw civil rights as a step towards political rights (like suffrage) and later, in the 20th century, social rights (like welfare).

Early Modern Period: 1700s-1800s

After 1750, countries like Britain and France built huge armies and navies. These were so expensive that hiring mercenary soldiers became less appealing. Rulers found troops from their own people and taxed them to pay for the military. Some believe this military buildup indirectly weakened the military's political power. Others agree that military conscription (drafting citizens) helped develop a broader role for citizens.

A new idea called the public sphere emerged, according to philosopher Jürgen Habermas. This was a space between government authority and private life. In this space, citizens could meet informally, share views on public matters, criticize government decisions, and suggest reforms. This happened in places like public squares, coffeehouses, museums, and restaurants. It also happened in media like newspapers and journals. The public sphere acted as a check on government power, as bad decisions could be criticized by the public. According to Schudson, the public sphere was a "playing field for citizenship."

Eastern Ideas of Citizenship

In the late 19th century, ideas about citizenship began to influence China. Discussions started about concepts like legal limits, definitions of monarchy and the state, parliaments, elections, a free press, and public opinion. Ideas like civic virtue, national unity, and social progress also became important.

Citizenship Today

Changes and Evolution

John Stuart Mill in his book On Liberty (1859) believed there should be no differences between men and women. He thought both were capable of citizenship. British sociologist Thomas Humphrey Marshall suggested that citizenship changed in stages: first, civil rights (like equality before the law), then political citizenship (like the power to vote), and later social citizenship (like state support in a welfare state). Marshall argued in the mid-20th century that modern citizenship included all three: civil, political, and social. He wrote that citizenship needed a strong sense of community and loyalty to a shared civilization.

Thinkers like Marc Steinberg saw citizenship emerge from class struggles linked to nationalism. People who were born in a country or became naturalized citizens gained more rights through ongoing interactions between individuals and the state. This led to a shared understanding of the powers of both the citizen and the state.

Nationalism grew. Many thinkers suggest that ideas of citizenship rights came from people strongly identifying with their birth nation. A modern type of citizenship allows people to participate in many different ways. Citizenship is not the only important relationship a person has. It has been seen as an "equalizing principle" because most people have the same status. One theory sees different types of citizenship spreading out from local to national to global levels.

The idea that taking part in lawmaking is key to citizenship continues today. For example, British journalist William Cobbett said the "greatest right" was having a share in "making the laws" and then making sure those laws served "the good of the whole."

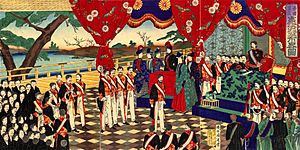

The idea of citizenship and Western forms of government began to appear in Asia in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Meiji Japan, popular social forces challenged traditional authority. Through talks and agreements, a period of "expanding democracy" began. More military activity led to a larger state and territory, which increased the power of the military and the Japanese emperor. But this also led to popular resistance, struggles, and bargaining, which expanded the role of citizens in early 20th century Japan.

Citizenship Today: Rights and Responsibilities

The idea of citizenship is hard to define because it connects to many other parts of society. These include the family, military service, the individual, freedom, religion, ideas of right and wrong, ethnicity, and how a person should behave. According to British politician Douglas Hurd, citizenship is basically doing good for others. When a nation has many different ethnic and religious groups, citizenship can be the only real bond that unites everyone equally. It gives people a universal identity—as a legal member of a nation—beyond their ethnic ties.

But there are clear differences between ancient and modern citizenship. While modern citizenship still values political participation, it's usually done through "elaborate systems of political representation at a distance," like representative democracy. This happens under the "shadow of a permanent professional administrative apparatus." Unlike ancient times, modern citizenship is much more passive. Actions are often delegated to others. Citizenship is often a limit on acting, not a push to act. Still, citizens know their duties to authorities, and they know these bonds "limit their personal political freedom in a very deep way." However, some disagree that the contrast between ancient and modern citizenship is so sharp. One theorist suggested that "modern" aspects of passive citizenship, like tolerance and respecting others, were also present in ancient times.

Citizenship can be seen as both a status and an ideal. Sometimes, talking about citizenship brings up many theories and the chance for social reform. It suggests a model of what a person should do in relation to the state.

Some thinkers see the modern idea of individualism as sometimes fitting with citizenship, and other times opposing it. The modern individual and the modern citizen seem similar, but too much individualism can lead to a "crisis of citizenship." Another agreed that individualism can harm citizenship. Another sees citizenship as a big challenge between the individual and society, and between the individual and the state. It raises questions like: should a person focus on the common good or their own good? In a Marxist view, the individual and the citizen were both "necessary" to each other, but also in conflict. Habermas suggested that while citizenship grew to include more people, the public sphere shrank and became more about business. Serious debate lessened, and media focused more on short statements and political scandals. In this process, citizenship became more common but meant less. Political participation declined for most people.

Other thinkers say citizenship is a mix of competing ideas. For example, sociologist T. H. Marshall suggested that citizenship was a contradiction between "formal political equality" (like voting rights) and "extensive social and economic inequality." Marshall saw citizenship as a way to bridge these two issues. A rich person and a poor person were equal as citizens, but separated by economic inequality. Marshall saw citizenship as the basis for giving social rights. He argued that extending these rights would not harm social classes or end inequality. He saw capitalism as a dynamic system with constant clashes between citizenship and social class. How these clashes played out shaped a society's political and social life.

Citizenship was not always about including everyone. It was also a powerful force to exclude people at the edges of society, like outcasts and illegal immigrants. In this sense, citizenship was not just about getting rights. It was also a struggle to "reject claims of entitlement by those initially residing outside the core, and later, of migrant and immigrant labor." But one thinker described democratic citizenship as generally inclusive. They wrote that democratic citizenship:

... (democratic citizenship) extends human, political and civil rights to all inhabitants, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, or culture. In a civic state, which is based on the concept of such citizenship, even foreigners are protected by the rule of law."

Different Views of Citizenship Today

Citizenship today often has two very different ideas, which are sometimes in tension.

Liberal-Individualist View

The liberal-individualist idea of citizenship worries that the government might harm the individual's status. This view talks about "needs" and "entitlements" necessary for human dignity. It focuses on making material things and a person's economic strength. Society is seen as a "market-based association of competitive individuals." From this view, citizens are independent beings with duties to pay taxes, obey the law, do business, and defend the nation if attacked. But they are mostly passive politically. This idea of citizenship is sometimes called conservative. This is because passive citizens want to protect their private interests, and private people have a right to be left alone. This idea was partly expressed by John Rawls. He believed every person has an "equal right to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic rights and liberties." He also thought society should try to benefit the "least advantaged members of society." But this idea has been criticized. Some say it can lead to a "culture of subjects" and a "decline of public spirit." This is because economic man, or homo economicus, is too focused on money to take part in civic activities and be a true citizen.

Civic-Republican View

A different idea is that democratic citizenship can be based on a "culture of participation." This view is sometimes called the civic-republican or classical idea of citizenship. It focuses on how important it is for people to actively practice citizenship. Unlike the liberal-individualist view, the civic-republican view emphasizes a person's political nature. It sees citizenship as an active, not passive, activity. A problem with this idea, say critics, is that it might lead to the free rider problem. This is when some people ignore basic citizenship duties and benefit from the efforts of others. This view stresses the democratic participation in citizenship. It can "channel legitimate frustrations and grievances" and bring people together to focus on common concerns. This can lead to a politics of empowerment, according to Dora Kostakopoulou. Like the liberal-individualist view, it worries about government harming individuals. But it is more concerned that government will interfere with places where people can practice citizenship in the public sphere, rather than taking away specific citizenship rights. This sense of citizenship has been called "active and public citizenship" and sometimes a "revolutionary idea." Most people today live as citizens according to the liberal-individualist idea but wish they lived more like the civic-republican ideal.

Other Perspectives

The topic of citizenship, and political discussions about it, can be a battleground for different ideologies. In Canada, citizenship and related issues like civic education are "hotly debated." Many academics still believe that trying to define one "unitary theory of citizenship" that describes it in every society, or even in one society, would be pointless. Citizenship has been described as "multi-layered belongings"—different attachments, bonds, and loyalties. This is the view of Hebert & Wilkinson, who suggest there isn't one single view of citizenship but "multiple citizenship" relationships, as each person belongs to many different groups that define them.

Sociologist Michael Schudson looked at changing patterns of citizenship in U.S. history. He suggested there were four main periods:

- The colonial era: White men who owned property gave authority to "gentlemen." Most people did not participate as citizens. Early elections didn't get much interest and had low voter turnout. They mostly showed the existing social order. Representative assemblies "barely existed" in the 18th century.

- The 19th century: Political parties became important to win jobs. Citizenship meant party loyalty.

- The 20th century: The ideal citizen was an "informed voter," choosing rationally (voting) based on information from newspapers and books.

- Later 20th century: Citizenship became seen as a basis for rights and benefits from the government. Schudson predicted the rise of the monitorial citizen: people who watch for issues like corruption and government violations of rights.

Schudson noted that citizenship expanded to include groups like women and minorities who were once excluded, while political parties declined. Interest groups influenced lawmakers directly through lobbying. Politics became less important to citizens, who were often described as "self-absorbed."

In 21st-century America, citizenship is generally a legal marker showing a person is American. Duty is usually not part of citizenship. Citizens generally don't see themselves as having a duty to help each other, though officeholders are seen as having a duty to the public. Instead, citizenship is a bundle of rights, including getting help from the federal government. A similar pattern is seen in many Western nations. Most Americans don't think much about citizenship unless they are applying for a passport and traveling internationally. Feliks Gross sees 20th-century America as an "efficient, diverse, and civic system that gave equal rights to all citizens, regardless of race, ethnicity, and religion." According to Gross, the U.S. can be a "model of a modern civic and democratic state," even though discrimination and prejudice still exist. The exception, of course, is that people living in America illegally see citizenship as a major issue.

Still, one constant is that experts agree the idea of citizenship is hard to define and lacks a precise meaning.

See also

- Citizenship

- Citizenship in the United States

- Cosmopolitanism

- Global citizenship

- Transnational citizenship

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |