History of local government in England facts for kids

The history of local government in England is all about how the ways towns and regions are managed have slowly changed over many centuries. England doesn't have a single, written rulebook for how its government works. Instead, its system is based on old traditions and powers given out long ago, often by the King or Queen, to older systems like the shires (which are like today's counties).

The idea of local government in England goes way back to the Anglo-Saxon times (around 700-1066 AD). Some parts of today's system still come from that era, especially the idea that towns and the countryside should be run separately. The feudal system, brought in by the Normans, was a big change for about 300 years. But after that, older ways of running things started to come back.

As England's population grew a lot during the Industrial Revolution, and people moved to cities, the old ways of local government just couldn't cope. Big changes happened gradually throughout the 1800s. The 1900s saw many attempts to find the perfect system. A huge change was the Local Government Act 1972, which created a two-level system of counties and districts in 1974. However, more changes since then mean that today's system is a mix of different setups.

Contents

How Local Government Began in England

Much of how local government works in England today comes directly from the old Kingdom of England. This is why some parts of England's system are different from those in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

The Kingdom of England grew out of the Saxon Kingdom of Wessex. It took over other kingdoms like Mercia and Northumbria, bringing all the Anglo-Saxon people together. So, some basic ideas of modern local government actually come from the ancient Wessex system.

Anglo-Saxon Times: Early Local Government (700–1066 AD)

Around 790 AD, the Kingdom of Wessex was split into areas called shires. Each shire was led by an Ealdorman, a powerful nobleman chosen by the King. The word 'Ealdorman' eventually combined with a Viking word to become 'Earl'.

Many of these shires have survived to this day as counties in England. For example, Defnascir became Devon, and Sumorsaete became Somerset. When Wessex took over other small kingdoms, they were also turned into shires, like Kent and Sussex. As Wessex expanded, new lands were divided into shires, often named after their main town, such as Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire. Most of the historic counties in southern England come from this time.

Another important person in the shire was the shire-reeve, which is where the word sheriff comes from. The shire-reeve was in charge of keeping the law and holding courts. While still important in some countries, the sheriff's role in England is mostly ceremonial now.

Below the shire, the Anglo-Saxon system was quite different. Shires were divided into areas called hundreds (or wapentakes in some northern areas). Each hundred was made up of ten groups of ten households. A group of ten households was called a tithing. The hundred system was flexible and changed with the population.

Hundreds had their own courts and were led by a 'hundred-man'. People in the hundreds were responsible for each other's actions, which helped keep order. Hundreds were also used to gather armies and collect taxes.

The Norman Conquest: Changes After 1066

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, they brought many changes to how the country was run locally. One of the biggest changes was the introduction of a strict feudal system. This meant that the King owned all the land and gave parts of it to his followers, who then controlled those areas.

Because feudal lords largely governed their own areas, the old Anglo-Saxon shire system became less important. However, shires (which the Normans called 'counties') remained the main geographical divisions. The Normans also created new counties in the north, like Yorkshire and Lancashire. Hundreds also continued to be used for administration, as shown in the Domesday Book, a big survey ordered by William the Conqueror. Over time, hundreds became more fixed areas, rather than changing groups of households.

Early Medieval Period: Towns Grow (1100–1300)

During the medieval period, local areas were mostly run by feudal lords. The Norman system made most people into serfs, meaning they were tied to the land. This made the hundreds less important. Instead, smaller areas like the parish, manor, or township became the basic local units.

Counties remained important for the legal system. The sheriff was still the main legal officer, and each county had its own court system. Over time, knights were appointed as 'Conservators of the Peace' to help keep order. These were the early versions of today's justices of the peace and magistrates' courts.

The Rise of Towns

The feudal system was good for controlling rural areas, but not for growing towns with complex economies. After the Norman Conquest, towns in England grew in importance as the population increased and trade expanded.

London, the biggest city, had special status even before the Normans. William the Conqueror gave London a royal charter in 1075, allowing it to govern itself and pay taxes directly to the King, rather than being part of the feudal system. This meant Londoners were 'burgesses' (free citizens) instead of serfs. Other towns also received charters from later kings, often to set up markets.

Henry II greatly increased the separation of towns from the countryside. He granted about 150 royal charters, turning towns into 'boroughs'. For an annual payment to the Crown, boroughs received special rights, like being free from feudal duties, holding markets, and collecting certain taxes.

These self-governing boroughs were the first truly modern part of local government in England. They were usually run by a town corporation, made up of 'aldermen' (town elders). These councils often chose their own new members, and a mayor was elected to lead for a set time. The idea of a town council running a town's affairs is still a key part of local government in England today.

Political Representation

The English Parliament started to develop in the 1200s. By 1297, it was decided that representatives in the House of Commons would come from counties and boroughs. Each shire sent two knights, and each borough sent two burgesses. This system stayed mostly the same for centuries, even as some towns grew huge and others shrank, until the Reform Act of 1832.

Late Medieval Period: Feudalism Declines (1300–1500)

By the 1300s, the feudal system in England was fading. The Black Death (1348–1350), which killed many people, effectively ended feudalism. The relationship between a lord and his people became more like that of a landlord and tenant. This left shires without a clear system of administration. The legal system and sheriffs remained, and local matters were handled by individual parishes or local landowners. In this time of "small government," there wasn't much need for higher levels of administration. Town councils continued to manage affairs in towns.

Counties Corporate

Some cities wanted even more independence than borough status offered. These cities were given full independence from the county, including their own sheriffs and courts. They were sometimes given control over surrounding countryside too. These were called "Counties Corporate," like the City and County of York, Bristol, and Chester. They were often referred to as "Town and County of..." or "City and County of...".

Modern Local Government Begins (1832-1974)

The Great Reform Act (1832)

Modern government in England really started with the Great Reform Act of 1832. This Act was driven by unfair practices in Parliament and the huge population growth during the Industrial Revolution. For a long time, some tiny villages, called "rotten boroughs," still sent representatives to Parliament, even though they had very few voters. Meanwhile, big new industrial towns had no representation at all.

Also, only wealthy male landowners could vote, and they could vote in every area where they owned property. This meant a small number of rich people had a lot of power. The Reform Act aimed to fix this by getting rid of rotten boroughs, giving new industrial towns their own representatives, and allowing more people to vote. While this didn't directly change local government, it pushed for reforms in other parts of government too.

The Municipal Corporations Act (1835)

After Parliament was reformed, the boroughs (towns with special charters) were next. The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 made sure that members of town councils had to be elected by local taxpayers. It also required councils to make their financial records public.

Before this Act, some town councils were like private clubs, where members chose new members for life. The Act reformed 178 boroughs right away, making them more democratic. Many industrial towns like Birmingham and Manchester quickly became boroughs under this new system. This Act made boroughs (now called "municipal boroughs") look much more like the modern, democratic councils we know today.

Public Welfare Reforms

The Industrial Revolution brought huge population growth, especially in cities, and created many poor people who couldn't support themselves. The small local governments couldn't handle these new problems. Between 1832 and 1888, several laws were passed to help.

In 1837, laws allowed rural parishes to join together as "Poor Law Unions" to better manage help for the poor. These unions could collect taxes and were run by a Board of Guardians, partly elected. In 1848, a Public Health Act created "Local Boards of Health" in towns to deal with sewage and disease. These boards had legal powers but were not full government bodies.

Later Public Health Acts in 1873 and 1875 created new organizations to handle both poor relief and public health. Urban areas got "sanitary districts" and rural areas got "rural sanitary districts."

Voting Rights Expanded

In local government elections, single women who paid taxes gained the right to vote in 1869. This right was confirmed and extended to some married women in the Local Government Act 1894.

The Local Government Act (1888)

By 1888, it was clear that the patchwork system of local government wasn't working well enough. The sanitary districts and parish councils were run by volunteers, and there was no clear responsibility if things went wrong. Also, the old county courts couldn't handle all the new "county business." People wanted elected officials to run local administration, just like in the reformed municipal boroughs. So, the Local Government Act 1888 was the first big attempt to create a standard system for local government in England.

The Act used the existing historic counties as a base. It created "administrative counties" for rural areas and "county boroughs" for large cities. There were 59 county boroughs, which were cities with populations over 50,000 (though some historic towns got this status with fewer people). These county boroughs were part of the geographical counties but were run separately. Each administrative county and county borough would have its own elected council to provide services. The Act also created the County of London for the capital city.

A second Act in 1894 (Local Government Act 1894) created a second level of local government: urban and rural districts. These districts took over from the sanitary districts. Municipal boroughs became a special type of urban district.

The 1894 Act also officially created civil parishes. These were like community councils for smaller, rural settlements. They took on some local responsibilities, while others went to the new district or county councils.

Attempts at Reform (1945-1974)

The new system worked well at first, and more county boroughs were created. However, after World War II, the creation of new county boroughs was paused because the government wanted to review local government. Various commissions were set up to recommend changes, but their ideas were often not fully put into action.

In 1965, a major reform happened in London. The old counties of London and Middlesex were abolished, and a new county called Greater London was formed. This new county was divided into 32 metropolitan boroughs. This London reform gave some ideas for the next big nationwide change in 1974.

The Redcliffe-Maud Report in 1969 suggested a system of single-level "unitary authorities" for most of England, with a two-level system only for big metropolitan areas. However, the Conservative Party won the 1970 election and preferred a two-level system.

The Local Government Act (1972)

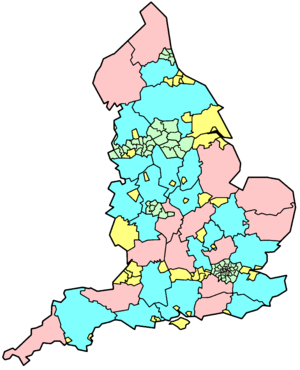

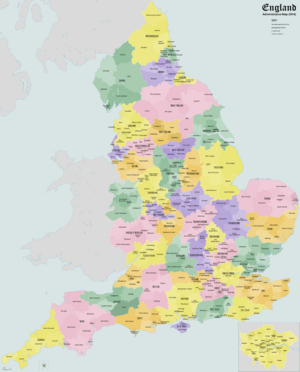

The Local Government Act 1972 brought the most uniform and simple system of local government to England. It basically wiped out all the old administrative areas and started fresh. All previous types of districts and counties were abolished, except for Greater London and the Isles of Scilly.

The goal was a uniform two-level system across the country. New counties were created, many based on the historic counties, but with some big changes. For example, Rutland joined Leicestershire, and Cumberland merged into Cumbria. The three parts of Yorkshire were replaced by North, South, and West Yorkshire. The Act also created six new "metropolitan" counties, like Greater London, for large urban areas. These included Greater Manchester and West Midlands.

Each new county got a county council to manage county-wide services like policing and social services. These new counties replaced the old ones for legal and ceremonial purposes too.

The second level of local government was different for metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties. Metropolitan counties were divided into metropolitan boroughs, which had more powers than the "districts" in non-metropolitan counties. For example, education was handled by metropolitan borough councils, but by county councils in non-metropolitan areas.

Old municipal boroughs were dissolved, but their special rights were often passed to the new district or metropolitan borough councils. Districts that received these rights could call themselves "borough councils," but it was just a ceremonial difference.

Civil parishes were kept in rural areas but abolished in large urban areas. The new system came into force on April 1, 1974, but its uniformity didn't last long.

Further Reforms (1974-Present)

Metropolitan County Councils Abolished

The uniform two-level system only lasted 12 years. In 1986, the metropolitan county councils and the Greater London Council were abolished by the Local Government Act 1985. This gave the metropolitan and London boroughs more independence, similar to the old county borough status. This meant that seven counties effectively stopped existing as administrative bodies, but they continued to exist as geographical areas for things like police forces. This led to the idea of "ceremonial counties" which still have a Lord Lieutenant and Sheriff.

Local Government Act (1992)

By the 1990s, it was clear that the "one-size-fits-all" approach of 1974 wasn't working everywhere. Larger towns outside the metropolitan counties, like Bristol and Plymouth, missed having control over services like education. The abolition of metropolitan county councils in 1986 meant their boroughs became "unitary" (single-level) authorities, and other big cities wanted the same.

The Local Government Act (1992) set up a commission to recommend where unitary authorities should be created. It was too expensive to make the whole country unitary, and some two-level systems worked well. The commission suggested that some counties become entirely unitary, some cities become unitary while the rest of their county remained two-level, and some counties stay as they were.

Some unpopular new counties created in 1974, like Cleveland, Humberside, and Avon, were split into new unitary authorities. This gave cities like Hull, Bristol, and Middlesbrough more local control. Rutland also got its independence back as a unitary authority.

This created a mixed system. To clarify things, the Lieutenancies Act 1997 officially separated local authority areas from the geographical concept of a county. The lieutenancies became known as ceremonial counties, which are now mainly for ceremonial purposes.

More Unitary Authorities After 2000

After 2000, even more changes happened, making the system even more varied. Several counties became unitary authorities, either by getting rid of their districts (like Cornwall) or by being divided into two or more unitary areas (like Bedfordshire).

The Labour government (1997–2010) had plans for eight regional assemblies across England to give more power to regions. However, only a London Assembly (with a directly elected Mayor) was set up. A vote in 2004 rejected a proposed North-East Assembly, effectively ending those plans.

Local Enterprise Partnerships

In 2010, the government announced the creation of local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) to replace regional development agencies. These LEPs are partnerships between local authorities and businesses, aiming to boost local economies.

Combined Authorities

The abolition of metropolitan county councils and regional development agencies meant there were no local government bodies with a broad strategy for major urban areas. In 2010, the government approved the creation of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority. These "combined authorities" are now used as a way for metropolitan areas to gain more powers and funding. By 2014, combined authorities were set up for South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, and other areas like the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. More combined authorities are being planned.

The City of London: A Special Case

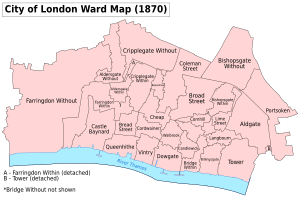

The City of London is a unique exception in the history of English local government. This refers only to the small, historic "Square Mile" financial district, not the wider Greater London area. It has a special relationship with the Crown and has kept many old traditions.

The City of London has been self-governing since the time of Alfred the Great and quickly gained independence after the Norman Conquest. Unlike most other cities, it was not reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 and has never been.

In the big local government reforms of 1888, the City of London was not made into a county borough or a district. It remained separate from the new County of London. Even in 1974, its special status was kept, and it wasn't included in any of the London boroughs created in 1965. It became part of the wider Greater London county, acting like a 33rd borough.

When the Greater London Council was abolished in 1986, the City of London went back to being a unitary authority (like the London boroughs). Under the Lieutenancies Act 1997, it is now considered its own ceremonial county, separate from the Greater London ceremonial county. However, it is part of the modern Greater London region and falls under the strategic management of the Greater London Authority.

The City of London still has some non-democratic elements in its local government. This is because its services are used by about 450,000 workers who don't live there, compared to only about 7,200 permanent residents. Businesses in the City can also vote in local elections, a practice abolished elsewhere in England in 1969. This ancient system is still being reviewed.

The City of London also has a different type of ward system than elsewhere, which is another old remnant of ancient local government. These wards are permanent parts of the City, not just electoral districts.

Images for kids

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |