England in the Late Middle Ages facts for kids

The Late Middle Ages in England lasted from the 13th century until 1485. This period began with Henry III becoming king and ended when the Tudor dynasty took the throne. Many historians see 1485 as the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the English Renaissance and early modern Britain.

When Henry III became king, England had only a small part of its lands left in Gascony, France. English kings had to pay respect to the French king for these lands. Also, many powerful nobles, called barons, were rebelling. Henry's son, Edward I, became king in 1272. He brought back royal power and took control of Wales and most of Scotland.

His son, Edward II, lost control of Scotland after being defeated at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. Edward II was later removed from power. In 1330, his son, Edward III, became king. Arguments over Gascony led Edward III to claim the French throne. This started the Hundred Years' War, where England had some big wins. But France fought back during the reign of Edward III's grandson, Richard II.

The 14th century was a tough time. The Great Famine and the Black Death were terrible events. They killed about half of England's people. This caused big problems for the economy and changed the old political system. With fewer farm workers, much farmland was turned into pastures, mostly for sheep. This led to social unrest, like the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Richard II was removed by Henry of Bolingbroke in 1399. Henry became Henry IV and started the House of Lancaster. He also restarted the war with France. His son, Henry V, won a huge victory at Agincourt in 1415. He took back Normandy and made sure his baby son, Henry VI, would inherit both the English and French crowns. But Henry V died unexpectedly in 1421. The French fought back again, and by 1453, England had lost almost all its lands in France.

Henry VI was a weak king. He was eventually removed from power during the Wars of the Roses. Edward IV became king, starting the House of York. After Edward IV died, his brother Richard III took the throne. But in 1485, Henry Tudor invaded and won the Battle of Bosworth Field. This battle ended the Plantagenet dynasty and started the Tudor rule.

During this time, the English government changed a lot. The Parliament of England became very important. Women also played a key role in the economy. Noblewomen managed their estates when their husbands were away. English people started to feel superior to their neighbours in the British Isles. New religious groups came to England, and pilgrimages became popular. But a new religious movement called Lollardy also appeared. The Little Ice Age made farming and living conditions harder. Economic growth slowed down in the late 13th century due to too many people, not enough land, and poor soil. New ideas in technology and science came from Greek and Islamic thinkers. In wars, kings started using hired soldiers, and having enough money became very important. By Edward III's time, armies were smaller but better equipped. Medieval England also produced beautiful art, literature, and music. Architecture changed from Norman to the more ornate Early English Gothic style.

Political History

The Plantagenet Kings

How the Plantagenets Began

The Plantagenet family gained control of Normandy and England by 1154. This happened through the marriage of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou to Empress Matilda. Geoffrey's son, Henry Curtmantle, married Eleanor of Aquitaine. This marriage greatly expanded their lands, which became known as the Angevin Empire. As Henry II, he made his control stronger and gained power in Wales and Ireland.

His son, Richard I, was often away from England, focusing on crusades and his French lands. Richard's brother, John, lost many battles in France. This weakened his power in England. His English nobles rebelled and forced him to sign the Magna Carta. This document limited the king's power and set up common law. Magna Carta was important for many political struggles over the next two centuries. But both the king and the nobles often ignored it. This led to the First Barons' War. The rebel nobles even invited Prince Louis of France to invade. King John died, and William Marshal became the protector for the young Henry III. Some historians say this marked the end of the Angevin period and the start of the Plantagenet dynasty.

Henry III (1216–1272)

When Henry III became king in 1216, France held much of his land in Europe. Many nobles were also rebelling in the First Barons' War. William Marshal won the war with victories at Lincoln and Dover in 1217. This led to the Treaty of Lambeth, where Louis gave up his claims. After the war, the Magna Carta was reissued as a guide for future government.

Even with the treaty, fighting continued. Henry had to give up more power to the new French king, Louis VIII, and his stepfather, Hugh X of Lusignan. They took over more of Henry's lands in Europe. Henry felt he was like England's patron saint, Edward the Confessor, who also struggled with nobles. So, Henry named his first son Edward and built a grand shrine for the saint at Westminster.

The nobles did not want to pay for a war to get back Henry's lands in Europe. To get their support, Henry III reissued Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest. In return, he got a huge tax of £45,000. This was agreed upon in an assembly of nobles and bishops. This meeting allowed them to discuss the king's powers. Henry was forced to agree to the Provisions of Oxford. These were demands from nobles led by his brother-in-law, Simon de Montfort. The Provisions paid Henry's debts in exchange for big changes in government. Henry also had to sign the Treaty of Paris with Louis IX of France. He gave up the Dukedom of Normandy, Maine, Anjou, and Poitou, but kept the Channel Islands. This treaty meant English kings had to pay homage to the French king for their French lands. This was one of the reasons for the Hundred Years War.

Second Barons' War and Parliament

Tensions grew between the nobles and the king. Henry went back on the Provisions of Oxford. He got permission from the Pope in 1261 to break his oath. Both sides started raising armies. Prince Edward, Henry's oldest son, first thought about joining Simon de Montfort. He even supported holding a Parliament without his father. But then he decided to support his father.

Montfort's nobles took control of most of south-eastern England. During this war, Jewish communities were attacked. This was to destroy records of debts owed to them by the nobles. About 500 Jewish people died in London, and communities in Worcester and Canterbury were destroyed. At the Battle of Lewes in 1264, Henry and Edward were defeated and captured. Montfort then called the Great Parliament. This is seen as the first true English Parliament because it included representatives from cities and towns.

Edward escaped and raised an army. He defeated and killed Montfort at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. The rebels faced harsh punishment, and Henry's power was restored. Edward then left England to join a crusade. He was one of the last crusaders trying to take back the Holy Lands. Edward's small army only managed to help Acre. He survived an attack and left for Sicily, never crusading again. England's government was stable. When Henry III died, his son Edward I became king. The nobles swore loyalty to Edward even though he did not return for two years.

Edward I (1272–1307)

Conquest of Wales

From the start of his rule, Edward I wanted to organize his lands. He also wanted to be the main ruler in the British Isles. Wales had many small princedoms that often fought each other. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd ruled North Wales under the English king. But he had used England's civil wars to strengthen his position as Prince of Wales. He said his principality was "entirely separate" from England. Edward saw Llywelyn as a "rebel." Edward's strong will, military skill, and use of ships ended Welsh independence. Llywelyn was driven into the mountains and later died in battle.

The Statute of Rhuddlan brought Wales into the English legal system. When Edward's son was born, he was named the first English Prince of Wales. Edward's Welsh campaigns created one of the largest armies an English king had ever gathered. It combined strong Anglo-Norman cavalry with Welsh archers. This army laid the groundwork for later English victories in France. Edward spent about £173,000 on his two Welsh campaigns. Much of this went to building a network of castles to secure his control.

Domestic Policy

Edward is sometimes called "The English Justinian" because of his legal changes. But people debate if he was a reformer or just reacting to events. His wars left him in debt. This meant he needed more support from landowners, merchants, and traders. He raised taxes by calling Parliaments often. When Philip IV of France took the duchy of Gascony in 1294, Edward needed more money for war in France. To get financial help, Edward called a special meeting called the Model Parliament. It included nobles, church leaders, knights, and townspeople.

Edward made his power strong over the Church. He passed the Statutes of Mortmain, which stopped land from being given to the Church. He also strengthened the Crown's rights over old noble privileges. He made justice more uniform, raised income, and organized the legal system. He also made Parliament and common law more important through new laws. He surveyed local governments and updated laws from Magna Carta with the Statute of Westminster 1275. Edward also made economic changes. He taxed wool exports, which brought in nearly £10,000 a year. He also charged fees for gifts of land to the Church. Noble power was regulated by the Statute of Gloucester and Quo Warranto. The Statute of Winchester strengthened royal policing. The Statute of Westminster 1285 kept estates within families. This meant tenants could only hold property for life and could not sell it. Quia Emptores stopped tenants from subletting their properties and related services.

Expulsion of the Jews

Jews faced increasing hardship, especially after they were excluded from the protections of Magna Carta. This led to Edward expelling them from England. Christians were not allowed to lend money with interest by church law. So, Jewish people played a key role by providing this service. The kings taxed them heavily because they were direct subjects, without needing Parliament's approval. Edward's first big step was the Statute of Jewry. This law made all lending with interest illegal. It gave Jews fifteen years to buy farmland. However, public dislike made it impossible for Jewish people to move into trade or farming. Edward tried to clear his debts by expelling Jews from Gascony. He took their property and all debts owed to them. He made his tax demands more acceptable to his subjects by offering to expel all Jews in exchange. The heavy tax was passed, and the Edict of Expulsion was issued. This was very popular and quickly carried out.

Anglo-Scottish Wars

Edward claimed that the Scottish king owed him loyalty. This made relations between England and Scotland bitter for the rest of his rule. Edward wanted to create a united kingdom by marrying his son Edward to Margaret, Maid of Norway. She was the only heir to the Scottish throne. When Margaret died, there was no clear heir. Scottish nobles asked Edward to settle the dispute. Edward got the Scottish claimants to agree that he had "sovereign lordship" over Scotland. He chose John Balliol as king, who then swore loyalty to him.

Edward insisted that Scotland was not independent. He said that as sovereign lord, he could hear appeals against Balliol's decisions in England. This weakened Balliol's power. John, urged by his advisors, made an alliance with France in 1295. In 1296, Edward invaded Scotland. He removed Balliol from power and sent him away.

Edward was less successful in Gascony, which France took over. His wars were costing more than he had. He had huge debts from wars against Flanders and Gascony in France, and Wales and Scotland in Britain. The clergy refused to pay their share, and the Archbishop of Canterbury threatened to excommunicate them. Parliament did not want to pay for Edward's expensive and unsuccessful wars. Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford and Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk refused to serve in Gascony. The nobles presented a list of their complaints. Edward had to reconfirm the charters (including Magna Carta) to get the money he needed. A truce and peace treaty with the French king gave Gascony back to Edward.

Meanwhile, William Wallace had risen up in Balliol's name and taken back most of Scotland. But he was defeated at the Battle of Falkirk. Edward called a full Parliament, including elected Scottish representatives, to settle Scotland. The new government in Scotland included Robert the Bruce. But Bruce rebelled and was crowned king of Scotland. Despite being ill, Edward was carried north for another campaign. But he died on the way at Burgh by Sands. Edward had asked for his bones to be carried on Scottish campaigns and his heart to be taken to the Holy Land. But he was buried at Westminster Abbey. His plain black marble tomb was later painted with the words "Hammer of the Scots" and "Honour the vow." His son, Edward II, became king.

Edward II (1307–1327)

Edward II's coronation oath in 1307 was the first to say the king must uphold laws that the community "shall have chosen." The king was popular at first. But he faced three problems: unhappiness about war costs, his household spending, and his favorite, Piers Gaveston. When Parliament decided Gaveston should be exiled, the king had to agree. The king brought Gaveston back, but was forced to agree to the appointment of "Ordainers." These were led by his cousin, Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster. They were to reform the royal household, and Gaveston was exiled again.

Great Famine

In the spring of 1315, very heavy rain began in much of Europe. It kept raining through spring and summer, and the weather stayed cool. This caused widespread crop failures. Hay for animals could not be dried, so there was no food for livestock. Food prices started to rise, doubling in England between spring and midsummer. Salt, needed to preserve meat, was hard to get because it could not be made in the wet weather. Its price peaked between 1310–1320, reaching double the price of the decade before.

In the spring of 1316, it continued to rain. People across Europe were weak from lack of food. Everyone was affected, from nobles to peasants. But peasants, who were most of the population, had no extra food. The famine was worst in 1317 as the wet weather continued. Finally, in the summer, the weather returned to normal. But people were so weakened by diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis. Also, much of the seed for planting had been eaten. So, it was not until 1325 that food supplies returned to normal, and the population began to grow again.

Late Reign and Removal

The Ordinances were widely published to gain public support. But there was a struggle for ten years over whether to keep or cancel them. When Gaveston returned to England again, he was kidnapped and executed after a fake trial. This cruel act removed Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, and his supporters from power. Edward's humiliating defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 confirmed Bruce as an independent king of Scots. In England, this gave power back to Lancaster and Guy de Beauchamp, 10th Earl of Warwick. They had not joined the campaign, saying it went against the Ordinances. Edward finally cancelled the Ordinances after defeating Lancaster at the Battle of Boroughbridge and executing him in 1322.

The War of Saint-Sardos, a short conflict with France, indirectly led to Edward's overthrow. The French king used his court to overrule decisions in noble courts. As a French vassal, Edward felt this in Gascony. The French king was judging disputes between Edward and his French subjects. Edward could do little but watch his duchy shrink. Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent, decided to resist one such judgment. As a result, Charles IV declared the duchy lost.

Charles's sister, Queen Isabella, was sent to negotiate. She agreed to a treaty that required Edward to pay homage to Charles in France. Edward gave Aquitaine and Ponthieu to his son, Prince Edward. Prince Edward traveled to France to give homage instead. With the English heir in her power, Isabella refused to return to England. She demanded Edward II dismiss his favorites and also formed a relationship with Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March. The couple invaded England. Joined by Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, they captured the king. Edward II gave up his throne on the condition that his son would inherit it instead of Mortimer. He is generally believed to have been murdered at Berkeley Castle. In 1330, Edward III led a takeover, ending four years of control by Isabella and Mortimer. Mortimer was executed. Isabella was removed from power but treated well, living in luxury for 27 more years.

Edward III (1327–1377)

Renewal of the Scottish War

After the English were defeated by the Scots at Battle of Stanhope Park, the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton was signed in Edward III's name in 1328. Edward was not happy with this peace deal. But the new war with Scotland started from private actions, not royal ones. A group of English nobles, called The Disinherited, had lost land in Scotland because of the peace. They invaded Scotland and won a victory at the Battle of Dupplin Moor in 1332. They tried to make Edward Balliol king of Scotland instead of David II. But Balliol was soon driven out and had to ask Edward III for help.

The English king responded by besieging the important border town of Berwick. He defeated a large Scottish army trying to relieve the siege at the Battle of Halidon Hill. Edward put Balliol back on the throne and received a large amount of land in southern Scotland. However, these victories were hard to keep. Forces loyal to David II slowly regained control of the country. In 1338, Edward had to agree to a truce with the Scots.

Hundred Years' War

In 1328, Charles IV of France died without a son. His cousin Phillip of Valois and Queen Isabella, on behalf of her son Edward, were the main claimants to the throne. Philip became king. Edward III paid homage to Philip as Duke of Aquitaine. But the French king continued to put pressure on Gascony. Philip demanded that Edward hand over an exiled French advisor, Robert III of Artois. When Edward refused, Philip declared Edward's lands in Gascony and Ponthieu lost. In response, Edward formed an alliance of European supporters, promising over £200,000 in payment. Edward borrowed heavily from banks and wealthy merchants. He also asked Parliament for £300,000 in return for more concessions.

The delay in raising money allowed the French to invade Gascony. They also threatened English ports, while the English engaged in widespread piracy in the Channel. Edward declared himself king of France. This encouraged the Flemish people to rebel against the French king. Edward won a major naval victory at the Battle of Sluys, destroying most of the French fleet. Inconclusive fighting continued at the Battle of Saint-Omer and the Siege of Tournai (1340). But both sides ran out of money, and the fighting ended with the Truce of Espléchin. Edward III had achieved nothing militarily, and English public opinion was against him. Bankrupt, he cut his losses, ruining many people he could not repay.

Both countries were tired of war. Taxes were heavy, and the wool trade was disrupted. Edward spent the next few years paying off his huge debt. In Gascony, the war mixed with banditry. In 1346, Edward invaded from the Low Countries using a strategy called chevauchée. This was a large, extended raid for plunder and destruction. The English would use this throughout the war. The chevauchée made Philip VI of France's government look bad. It also threatened to make his vassals disloyal. Edward won two battles, the Storming of Caen and the Battle of Blanchetaque. He then found himself outmaneuvered and outnumbered by Philip. He was forced to fight at Crécy. The battle was a huge defeat for the French. This left Edward free to capture the important port of Calais. A later victory against Scotland at the Battle of Neville's Cross resulted in the capture of David II. This reduced the threat from Scotland.

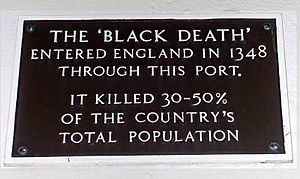

Black Death

According to a historical record, the plague arrived by ship from Gascony to Melcombe (now Weymouth) in Dorset. This happened just before June 24, 1348. From Weymouth, the disease spread quickly across the southwest. Bristol was the first major city hit. London was reached in the autumn of 1348, before most of the surrounding countryside. This was certainly by November, though some say as early as September 29. The full impact of the plague was felt in London early the next year. Conditions in London were perfect for the plague: narrow streets filled with sewage, overcrowded houses, and poor air flow.

By March 1349, the disease was spreading randomly across all of southern England. During the first half of 1349, the Black Death spread north. A second wave started when the plague arrived by ship at the Humber river. From there, it spread both south and north. In May, it reached York. During June, July, and August, it devastated the north. Some northern counties, like Durham and Cumberland, had been attacked by the Scots. This made them especially vulnerable to the plague. The plague is less strong in winter and spreads slower. The Black Death in England survived the winter of 1348–49. But it ended the following winter, and by December 1349, things were returning to normal. It took the disease about 500 days to cross the entire country.

The Black Death stopped Edward's wars. It killed between one-third and more than half of his people. The king passed the Ordinance of Labourers and the Statute of Labourers because of the labor shortage and social unrest after the plague. These labor laws were not enforced well, and the harsh rules caused anger.

Poitiers Campaign and Conflict Expansion (1356–1368)

In 1356, Edward, Prince of Wales, restarted the war. He led one of the most destructive chevauchées of the conflict. Starting from Bordeaux, he devastated the lands of Armagnac before turning east into Languedoc. Toulouse prepared for a siege, but the Prince's army was not equipped for one. So, he bypassed the city and continued south, looting and burning. Unlike large cities, rural French villages were not organized for defense. This made them much easier targets.

In a second great chevauchée, the Prince burned the suburbs of Bourges without capturing the city. He then marched west along the Loire River to Poitiers. There, the Battle of Poitiers resulted in a decisive English victory and the capture of John II of France. The Second Treaty of London was signed, promising a four million écus ransom. Valois family members were held hostage in London to guarantee it. John returned to France to raise his ransom. Edward gained control of Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine, and the coastline from Flanders to Spain. This restored the lands of the former Angevin Empire. The hostages quickly escaped back to France. John, horrified that his word had been broken, returned to England and died there.

Edward invaded France, hoping to take advantage of the popular rebellion of the Jacquerie. He hoped to seize the throne. No French army stood against him, but he could not take Paris or Rheims. In the later Treaty of Brétigny, he gave up his claim to the French crown. But he greatly expanded his territory in Aquitaine and confirmed his conquest of Calais.

Fighting in the Hundred Years' War often spread from French and Plantagenet lands to nearby kingdoms. This included a family conflict in Castile between Peter of Castile and Henry II of Castile. Edward, Prince of Wales, allied with Peter. He defeated Henry at the Battle of Nájera. But then he fell out with Peter, who could not pay him back. This left Edward bankrupt. The Plantagenets continued to interfere. John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, the prince's brother, married Peter's daughter Constance. He claimed the Crown of Castile in his wife's name. He arrived with an army, asking John I to give up the throne for Constance. John refused. Instead, his son married John of Gaunt's daughter, Catherine of Lancaster. This created the title Prince of Asturias for the couple.

French Resurgence (1369–1377)

Charles V of France restarted the fighting when Prince Edward refused a summons as Duke of Aquitaine. During Charles's reign, the Plantagenets were steadily pushed back in France. Prince Edward showed his brutal side at the Siege of Limoges. After the town opened its gates to John, Duke of Berry, he ordered the killing of 3,000 people, including men, women, and children. After this, the prince was too ill to fight or govern. He returned to England, where he soon died. He was the son of a king and the father of a king, but never a king himself.

Prince Edward's brother, John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, took over leadership of the English in France. Despite more chevauchées, which destroyed the countryside, his efforts were not effective strategically. The French commander, Bertrand Du Guesclin, used Fabian tactics. He avoided major English armies while capturing towns, including Poitiers and Bergerac. In another strategic blow, English control of the sea was lost. This happened with the terrible defeat at the Battle of La Rochelle. This hurt English sea trade and allowed Gascony to be threatened.

Richard II (1377–1399)

Peasants' Revolt

The 10-year-old Richard II became king after his father and grandfather died. The government was run by a council until he was old enough. The poor economy caused much unrest. His government collected several poll taxes to pay for wars. A tax of one shilling for everyone over 15 was very unpopular. This, along with enforcing the Statute of Labourers (which limited wages), caused an uprising in 1381. People refused to pay the tax.

Kent rebels, led by Wat Tyler, marched on London. At first, they only attacked properties linked to John of Gaunt. The young king himself is said to have met the rebels. They presented demands, including firing some ministers and ending serfdom. Rebels stormed the Tower of London and executed those hiding there. At Smithfield, more talks were arranged. But Tyler acted aggressively. In the fight, William Walworth, the Lord Mayor of London, attacked and killed Tyler. Richard took charge, shouting, "You shall have no captain but me." This statement was unclear on purpose to calm the situation. He had promised mercy. But once he had control, he hunted down, captured, and executed the other rebel leaders. All promises were taken back.

Deposition

A group of powerful nobles, including the king's uncle Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester, Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel, and Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick, became known as the Lords Appellant. They wanted to remove five of the king's favorites and control his increasingly harsh rule. Later, Henry Bolingbroke, John of Gaunt's son, and Thomas de Mowbray, 1st Duke of Norfolk, joined them.

At first, they succeeded in setting up a commission to govern England for one year. But they were forced to rebel against Richard. They defeated an army led by Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, at the Battle of Radcot Bridge. Richard was left with little power. As a result of the Merciless Parliament, de Vere and Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk, who had fled abroad, were sentenced to death in their absence. Alexander Neville, Archbishop of York, had all his property taken. Several of Richard's council members were executed.

After John of Gaunt returned from Spain, Richard was able to regain his power. He had Gloucester murdered in captivity in Calais. Warwick lost his title. Bolingbroke and Mowbray were exiled. When John of Gaunt died in 1399, Richard took away Henry of Bolingbroke's inheritance. Henry invaded England in response with a small force that quickly grew. Meeting little resistance, Henry removed Richard and crowned himself Henry IV of England. Richard died in captivity early the next year, probably murdered. This ended the main Plantagenet line.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (1399–1413)

Henry claimed the throne through his mother, who he said was a descendant of Edmund Crouchback. He claimed Edmund was Henry III's older son, set aside due to a deformity. But these claims were not widely believed. Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was the rightful heir to Richard II through his grandmother. As a child, he was not seen as a serious threat. As an adult, he never wanted the throne and served the House of Lancaster loyally. When Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, later plotted to use him to replace Henry's newly crowned son, Edmund told the new king, and the plotters were executed. However, the later marriage of Edmund's granddaughter to Richard's son combined their claims to the throne with that of the more junior House of York.

Henry restarted the war with France. But he faced money problems, poor health, and frequent rebellions. A Scottish invasion was defeated at the Battle of Homildon Hill. But this led to a long war with Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, for northern England. This was only resolved with the near complete destruction of the Percy family at the Battle of Bramham Moor. In Wales, Owain Glyndŵr's widespread rebellion was only put down in 1408. Many saw it as punishment from God when Henry later became ill with leprosy and epilepsy.

Henry V (1413–1421)

Henry IV died in 1413. His son, Henry V, was a successful and tough military leader. He knew that Charles VI of France's mental illness had caused instability in France. So, he invaded to assert the Plantagenet claims. He captured Harfleur, made a chevauchée to Calais, and won a huge victory over the French at the Battle of Agincourt on October 25, 1415. This was despite being outnumbered, outmaneuvered, and low on supplies.

In the following years, Henry recaptured much of Normandy. He also successfully arranged his marriage to Catherine of Valois. The resulting Treaty of Troyes stated that Henry's heirs would inherit the throne of France. However, conflict continued with the Dauphin. Henry's brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, was killed in the defeat at the Battle of Baugé in 1421. When Henry died in 1422, possibly from dysentery, his nine-month-old son, Henry VI of England, became king. The elderly Charles VI of France died two months later.

Henry VI (1421–1471)

Led by Henry's brother, John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, there were several more English victories, such as the Battle of Verneuil in 1424. But it was impossible to keep fighting at this level. Joan of Arc helped force the lifting of the siege of Orleans. French victory at the Battle of Patay allowed the Dauphin to be crowned at Reims. He continued to use successful Fabian tactics, avoiding direct attacks and using logistical advantages. Joan was captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, tried as a witch, and burned at the stake.

During the time when Henry VI was a child king, the war caused political division among the Plantagenet family. Bedford wanted to defend Normandy, Humphrey of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Gloucester, just Calais, but Cardinal Beaufort wanted peace. This division led to Humphrey's wife being accused of using witchcraft to put him on the throne. Humphrey was later arrested and died in prison.

The English refusal to give up their claim to the French crown at the congress of Arras allowed the former Plantagenet ally, Philip III, Duke of Burgundy, to make peace with Charles. This gave Charles time to reorganize his armies into a modern professional force. The French retook Rouen and Bordeaux, regained Normandy, won the Battle of Formigny in 1450, and, with victory at the Battle of Castillon in 1453, ended the war. England was left with only Calais and its surrounding area in France.

Henry VI was a weak king. He was seen as vulnerable to powerful nobles who had their own private armies. These nobles took advantage of the old system of feudal levies being replaced by taxation. This led to rivalries that often turned into armed fights, like the Percy–Neville feud. The common goal of the war in France had ended. So, Richard, Duke of York, and Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, used their connections to challenge the king. The gentry joined different groups based on their own private feuds. Henry became the focus of unhappiness. The population, farm production, prices, wool trade, and credit all declined in the Great Slump. Most seriously, in 1450, Jack Cade led a rebellion. He tried to force the king to fix economic problems or give up his throne. The uprising was stopped, but the situation remained unstable.

Wars of the Roses

Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York's feelings about Henry's marriage contract, which included giving up Maine and extending the truce with France, led to him being appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. This conveniently removed him from English and French politics, where he had influence as a descendant of both Lionel, Duke of Clarence, and Edmund, Duke of York. Richard was aware of what happened to Duke Humphrey at the hands of the Beauforts. He also suspected Henry intended to name Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, as heir instead of him. So, he raised an army when he returned to England. Richard claimed to be a reformer but was possibly plotting against his enemy Somerset. Armed conflict was avoided because Richard lacked noble support and was forced to swear loyalty to Henry. However, when Henry had a mental breakdown, Richard was named regent. Henry himself was trusting and not a man of war. But Margaret was more assertive, showing open dislike toward Richard, especially after the birth of a son who solved the succession question.

When Henry regained his sanity, the court party took back power. Richard of York and the Nevilles, who were related by marriage and had been angered by Henry's support of the Percys, defeated them in a small fight called the First Battle of St Albans. Perhaps as few as 50 men were killed. But among them were Somerset and two Percy lords, Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland, and Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford. This created feuds that would be impossible to settle. Clifford's son is said to have later murdered Richard's son Edmund. The ruling class was deeply shocked, and they tried to make peace.

Threatened with treason charges and lacking support, York, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, and Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, fled abroad. The Nevilles returned to win the Battle of Northampton, where they captured Henry. When Richard joined them, he surprised Parliament by claiming the throne. He then forced through the Act of Accord. This stated that Henry would remain king for his lifetime, but York would succeed him. Margaret found this disregard for her son's claims unacceptable, so the conflict continued. York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield along with his son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury.

House of York

Edward IV (1461–1483)

The Scottish queen Mary of Guelders supported Margaret, and a Scottish army looted southern England. London resisted, fearing plunder. Then, it enthusiastically welcomed York's son, Edward, Earl of March. Parliament confirmed that Edward should be made king. Edward was crowned as Edward IV after making his position strong with a victory at the Battle of Towton.

Edward favored the Woodville family, who had supported the Lancastrians, after his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. This led Warwick and Edward's brother, George Duke of Clarence, to help Margaret remove Edward and return Henry to the throne in 1470. Edward and his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, fled. But when they returned the next year, Clarence switched sides at the Battle of Barnet. This led to the death of the Neville brothers. The later Battle of Tewkesbury brought the end of the last male line of the Beauforts. The execution of Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, on the battlefield and the later murder of Henry VI ended the House of Lancaster.

Edward V and Richard III (1483–1485)

By the mid-1470s, the victorious House of York seemed safely established. It had seven living male princes. But it quickly brought about its own end. Clarence plotted against his brother and was executed. After Edward's early death in 1483, his son Edward Prince of Wales became king. But Parliament declared him and his brother Richard, Duke of York illegitimate. This was based on a claim of a prior marriage to Lady Eleanor Talbot, making Edward's marriage invalid. Richard became king as Richard III. The fate of Edward's sons, known as the Princes in the Tower, remains a mystery. Richard's own son died before him. In 1485, an invasion of foreign hired soldiers was led by Henry Tudor. He claimed the throne through his mother, Margaret Beaufort. After Richard was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field, Tudor became king as Henry VII. This founded the Tudor dynasty and ended the Plantagenet line of kings.

Government and Society

Governance and Social Structures

When Edward I became king in 1272, he brought back royal power. He improved royal finances and appealed to the wider English elite. He used Parliament to approve new taxes and hear complaints about local government problems. This political balance broke down under Edward II. Fierce civil wars broke out in the 1320s. Edward III restored order with the help of most nobles. He ruled through the exchequer (treasury), the common bench (court), and the royal household. This government was better organized and larger than ever before. By the 14th century, the king's traveling chancery (office) had to stay permanently in Westminster.

Edward used Parliament even more than previous kings. He used it for general administration, making laws, and raising taxes for the wars in France. The royal lands and their incomes had decreased over the years. So, more frequent taxes were needed to support the king's plans. Edward held grand events to unite his supporters around the idea of knighthood. The ideal of chivalry continued to grow throughout the 14th century. This was seen in the growth of knightly orders (like the Order of the Garter), big tournaments, and round table events.

By the time Richard II was removed in 1399, the power of the major nobles had grown a lot. Strong rulers like Henry IV could control them. But when Henry VI was a child king, these nobles controlled the country. The nobles depended on their income from rent and trade. This allowed them to keep groups of paid, armed followers, often wearing special uniforms. They also bought support among the wider gentry. This system was called "bastard feudalism." Their influence was felt in the House of Lords at Parliament and through the king's council. The gentry and wealthier townspeople had growing influence through the House of Commons. They opposed raising taxes for the French wars.

In the 1430s and 1440s, the English government faced major financial problems. This led to the crisis of 1450 and a popular revolt led by Jack Cade. Law and order got worse. The king could not stop the fighting between different nobles and their followers. The resulting Wars of the Roses saw a brutal increase in violence between the noble leaders on both sides. Captured enemies were executed, and family lands were taken away. By the time Henry VII took the throne in 1485, England's government and social structures had been greatly weakened. Whole noble families had died out.

Women

Medieval England was a patriarchal society. Women's lives were greatly shaped by beliefs about gender and power at the time. However, the position of women changed a lot based on things like their social class, whether they were single, married, widowed, or remarried, and where they lived. Big differences between genders remained throughout this period. Women usually had fewer life choices, less access to jobs and trade, and fewer legal rights than men.

As government institutions grew, the role of queens and their households in formal government became smaller. Married or widowed noblewomen remained important supporters of culture and religion. They also played a big part in political and military events, even if writers were unsure if this was proper behavior. Like in earlier centuries, most women worked in agriculture. But roles became more clearly divided by gender. For example, ploughing and managing fields were men's work. Dairy production became mostly women's work.

After the Black Death, many women became widows. In the wider economy, there was a shortage of workers, and land was suddenly easy to get. In rural areas, peasant women could have a better standard of living than ever before. But the amount of work done by women might have increased. Many other women traveled to towns and cities, so much so that they outnumbered men in some places. There, they worked with their husbands or in a limited number of jobs. These included spinning, making clothes, selling food, and being servants. Some women became full-time ale brewers. But they were later pushed out of business by the male-dominated beer industry in the 15th century. Higher-status jobs and apprenticeships, however, remained closed to women. As before, noblewomen used their power on their estates when their husbands were away. They also defended them in sieges and small battles if needed. Wealthy widows who successfully claimed their rightful share of their late husband's property could live as powerful members of the community on their own.

Identity

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the English began to see themselves as better than the Welsh, Scots, and Bretons. They thought of themselves as civilized, rich, and truly Christian. Meanwhile, the Celtic fringe (Wales, Scotland, Ireland) was seen as lazy, wild, and backward. After the invasion of Ireland in the late 12th century, similar feelings were expressed about the Irish. These differences were made clearer in English laws in the 14th century.

The English also felt strongly about foreign traders living in special areas in London during the Late Middle Ages. There was much hostility towards Jews, which led to their expulsion. But Italian and Baltic traders were also seen as foreigners. They were often attacked during economic downturns. Even within England, different identities existed, each with its own sense of status. Regional identities could be important. For example, people from Yorkshire had a clear identity within English society. Professional groups, like lawyers, also had distinct identities. They sometimes fought openly with others in cities like London.

English began to be used as a second language at court during Edward I's reign. Edward III encouraged English to be used again as the official language of courts and Parliament. The Statute of Pleading made English the language of royal and noble courts. It was officially adopted for diplomatic language instead of French during Henry IV's reign. Many scholars believe the Hundred Years War was important in creating an English national identity. This is shown by the use of propaganda, the growth of insults and national stereotypes, and intense debates between scholars from different kingdoms. Maps also showed national boundaries. The patron Saint George and the Church played a central role in delivering a national message. The war saw changes in armies. Lower ranks identified with a national cause and answered calls to arms. Near-permanent taxation developed, making the general population invested in a national effort. There was also the growth of knightly orders like the Garter. The monarchy and Parliament became increasingly central to English life.

Religion

Religious Institutions

New religious orders were introduced into England during this period. The French Cluniac order became popular, and their houses were built in England from the late 11th century. The Augustinians spread quickly from the early 12th century. Later in the century, the Cistercians reached England. They built houses with stricter monastic rules, creating great abbeys like Rievaulx and Fountains. By 1215, England had over 600 monastic communities. But new donations slowed down in the 13th century, causing long-term money problems for many institutions.

Dominican and Franciscan friars arrived in England in the 1220s. They established 150 friaries by the end of the 13th century. These mendicant (begging) orders quickly became popular, especially in towns. They greatly influenced local preaching. Religious military orders that became popular across Europe from the 12th century also gained property in England. These included the Templars, Teutonic Order, and Hospitallers.

Pilgrimage

Pilgrimages were a popular religious practice throughout the Middle Ages in England. Pilgrims usually traveled short distances to a shrine or a specific church. They did this either to do penance for a sin or to seek relief from an illness. Some pilgrims traveled further, either to more distant sites within Britain or, in a few cases, to Europe. Major shrines in the Late Middle Ages included those of Thomas Becket at Canterbury, Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey, Hugh of Lincoln, William of York, Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury (buried in France), Richard of Chichester, Thomas Cantilupe of Hereford, St Osmund of Salisbury, and John of Bridlington.

Heresy

In the 1380s, new challenges to the Church's traditional teachings appeared. These came from the ideas of John Wycliffe, a scholar at Oxford University. Wycliffe argued that scripture (the Bible) was the best guide to understanding God's intentions. He believed that the superficial nature of the liturgy (church services), along with the Church's wealth and senior churchmen's role in government, distracted from studying the Bible. A loose movement, including many gentry members, followed these ideas after Wycliffe's death in 1384. They tried to pass a Parliamentary bill in 1395. The authorities quickly condemned this movement and called it "Lollardy." English bishops were tasked with controlling this trend. They stopped Lollard preachers and enforced the teaching of proper sermons in local churches. By the early 15th century, fighting Lollard teachings became a key political issue. Henry IV and his Lancastrian followers championed this, using the powers of both church and state to fight the heresy.

Economy and Technology

Geography

England had diverse geography in the medieval period. This ranged from the Fenlands of East Anglia and the heavily wooded Weald, to the upland moors of Yorkshire. Despite this, medieval England generally had two zones. These were roughly divided by the rivers Exe and Tees. The south and east of England had lighter, richer soils. These could support both crop growing and animal farming. The poorer soils and colder climate of the north and west mainly supported animal farming. Slightly more land was covered by trees than in the 20th century. Bears, beavers, and wolves lived wild in England. Bears were hunted to extinction by the 11th century, and beavers by the 12th.

Of the 10,000 miles of roads built by the Romans, many were still used. Four were especially important: the Icknield Way, the Fosse Way, Ermine Street, and Watling Street. These criss-crossed the entire country. The road system was good enough for the time. However, it was much cheaper to transport goods by water. The major river networks were key transport routes. Many English towns were navigable inland ports.

For much of the Middle Ages, England's climate was different from today. Between the 9th and 13th centuries, England had the Medieval Warm Period. This was a long time of milder temperatures. For example, in the early 13th century, summers were about 1°C warmer than today, and the climate was slightly drier. These warmer temperatures allowed poorer land to be farmed. Grapevines could also be grown quite far north. The Warm Period was followed by several centuries of much cooler temperatures, called the Little Ice Age. By the 14th century, spring temperatures had dropped a lot, reaching their coldest in the 1340s and 1350s. This cold end to the Middle Ages greatly affected English farming and living conditions. England's environment continued to be shaped throughout the period. This included building dykes to drain marshes, clearing trees, and large-scale extraction of peat. Managed parks for hunting game, like deer and boars, were built as status symbols by nobles from the 12th century.

Economy

The English economy was mainly agricultural. It depended on growing crops like wheat, barley, and oats using an open field system. It also involved raising sheep, cattle, and pigs. Farmland was usually organized around manors. It was divided between fields the landowner managed directly (called demesne land) and most fields cultivated by local peasants. These peasants paid rent to the landowner either by working on the lord's demesne fields or by paying cash and produce. By the 11th century, a market economy was thriving across much of England. Towns in the east and south were heavily involved in international trade. About 6,000 watermills were built to grind flour. This freed up workers for other farming tasks.

Economic growth began to slow down at the end of the 13th century. This was due to too many people, not enough land, and poor soil. The Great Famine severely shook the English economy, and population growth stopped. The first outbreak of the Black Death in 1348 then killed about half the English population.

Some scholars argue that peasants who survived famine, plague, and disease found their situation much better. The period 1350-1450 was a golden age of prosperity and new opportunities for them. Land was plentiful, wages were high, and serfdom had almost disappeared. It was possible to move around and rise higher in life. Younger sons and women especially benefited. However, as population growth resumed, peasants again faced hardship and famine.

Conditions were less favorable for the great landowners. The farming sector shrank quickly. Higher wages, lower prices, and falling profits led to the end of the old demesne system. This brought about the modern farming system, where cash rents were charged for land. As returns on land fell, many estates, and sometimes entire settlements, were simply abandoned. Nearly 1,500 villages were deserted during this period. A new class of gentry emerged who rented farms from the major nobility. The government tried to control wages and spending. But these efforts largely failed in the decades after the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

The English cloth industry grew at the start of the 15th century. A new class of international English merchants emerged, usually based in London or the Southwest. They prospered at the expense of older, shrinking economies in eastern towns. These new trading systems led to the end of many international fairs and the rise of chartered companies. Fishing in the North Sea expanded into deeper waters, supported by commercial investment from major merchants.

However, between 1440 and 1480, Europe entered a recession. England suffered the Great Slump. Trade collapsed, driving down farm prices, rents, and ultimately the acceptable levels of royal taxation. The resulting tensions and unhappiness played an important part in Jack Cade's popular uprising in 1450 and the later Wars of the Roses. By the end of the Middle Ages, the economy had begun to recover. Significant improvements were being made in metalworking and shipbuilding. These would shape the early modern economy.

Technology and Science

Technology and science in England advanced a lot during the Middle Ages. This was partly driven by Greek and Islamic ideas that reached England from the 12th century. Many advances were made in scientific ideas. These included the introduction of Arabic numerals and improvements in units for measuring time. Clocks were first built in England in the late 13th century. The first mechanical clocks were installed in cathedrals and abbeys by the 1320s. Astrology, magic, and palm reading were also seen as important forms of knowledge in medieval England, though some doubted their reliability.

The period produced some important English scholars. Roger Bacon (around 1214–1294), a philosopher and friar, wrote works on natural philosophy, astronomy, and alchemy. His work laid the groundwork for future experiments in natural sciences. William of Ockham (around 1287–1347) helped combine Latin, Greek, and Islamic writings into a general theory of logic. "Ockham's Razor" was one of his famous ideas. Despite the limits of medieval medicine, Gilbertus Anglicus published the Compendium Medicinae. This was one of the longest medical works ever written in Latin. Important historical and science texts began to be translated into English for the first time in the second half of the 14th century. These included the Polychronicon and The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge were established during the 11th and 12th centuries, based on the model of the University of Paris.

Technological advances happened in many areas. Watermills to grind grain had existed during most of the Anglo-Saxon period, using horizontal mill designs. From the 12th century on, many more were built, ending the use of hand mills. The older horizontal mills were slowly replaced by a new vertical mill design. Windmills began to be built in the late 12th century and slowly became more common. Water-powered fulling mills (for cloth) and powered hammers first appeared in the 12th century. Water power was used to help in smelting (extracting metal) by the 14th century, with the first blast furnace opening in 1496. New mining methods were developed, and horse-powered pumps were installed in English mines by the end of the Middle Ages.

The introduction of hopped beer changed the brewing industry in the 14th century. New techniques were invented to better preserve fish. Glazed pottery became widespread in the 12th and 13th centuries. Stoneware pots largely replaced wooden plates and bowls by the 15th century. William Caxton and Wynkyn de Worde began using the printing press in the late 15th century. Transport links also improved. Many road bridges were either built or rebuilt in stone during the long economic boom of the 12th and 13th centuries. England's sea trade benefited from the introduction of cog ships. Many docks were improved and fitted with cranes for the first time.

Warfare

Armies

In the late 13th century, Edward I expanded the familia regis, which was the king's permanent military household. This was supported in war by feudal levies, which were armies raised by local nobles for a limited time during a campaign. This grew into a small standing army. It formed the core of much larger armies, up to 28,700 strong, mostly foot soldiers, for campaigns in Scotland and France.

By the time of Edward III, armies were smaller. But the soldiers were usually better equipped and had uniforms. The archers carried the longbow, a very powerful weapon. Cannons were first used by English forces at battles like Crécy in 1346. Soldiers began to be hired for specific campaigns. This practice may have sped up the development of private armies under "bastard feudalism." However, by the late 15th century, English armies were somewhat behind European standards. The Wars of the Roses were fought by inexperienced soldiers, often with old weapons. This allowed European forces that intervened in the conflict to have a big impact on battle outcomes.

English fleets in the 13th and 14th centuries usually included special ships, like galleys and large transport ships. They also used pressed merchant vessels, which were forced into service. These increasingly included cogs, a new type of sailing ship. Battles might happen when one fleet found another at anchor, like the English victory at Sluys in 1340. Or they could happen in open waters, like off the coast of Winchelsea in 1350. Raiding campaigns, such as the French attacks on southern England between 1338–1339, could cause great damage. Some towns never fully recovered from these attacks.

Fortifications

During the 12th century, the Normans began to build more castles out of stone. These had characteristic square keeps that served both military and political purposes. Royal castles were used to control key towns and forests. Noble castles were used by Norman lords to control their widespread lands. A feudal system called "castle-guard" was sometimes used to provide soldiers for the garrisons. Castles and sieges continued to become more advanced militarily during the 12th century. In the 13th century, new defensive town walls were built across England.

By the 14th century, castles combined defenses with luxurious living spaces. They often had fancy tiles, murals, glass windows, and landscaped gardens and parks. These buildings were often designed as a set of apartments to allow more privacy. Fashionable brick began to be used in some parts of the country, copying French styles. Architecture that looked like older defensive designs remained popular. Less is known about peasant houses during this period. However, many peasants seem to have lived in fairly large, timber-framed long-houses. The quality of these houses improved in the good years after the Black Death. They were often built by professional craftsmen.

Arts

Art

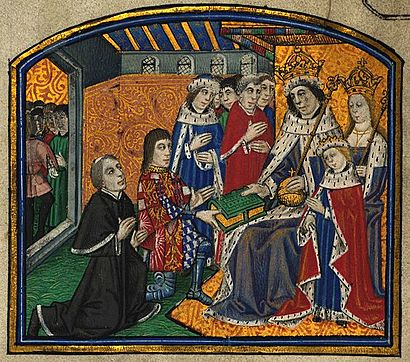

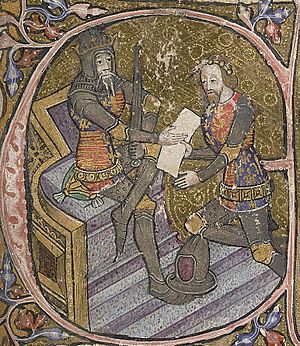

Medieval England produced art in the form of paintings, carvings, books, fabrics, and many useful but beautiful objects. A wide range of materials were used, including gold, glass, and ivory. The art usually highlighted the materials used in the designs. Stained glass became a common form of English art during this period. However, the colored glass for these works was almost entirely imported from Europe. Little early stained glass in England has survived. But it typically had both a decorative and educational purpose. Later works also honored the people who paid for the windows in their designs. English embroidery in the early 14th century was especially high quality. It regained its international reputation from Anglo-Saxon times. Works made by nuns and London professionals were exported across Europe, known as opus anglicanum.

During this period, manuscript painting in England became as good as any in Europe. This was seen in Romanesque works like the Winchester Bible and the St Albans Psalter. Then came early Gothic ones like the Queen Mary Psalter and Tickhill Psalter. English illumination declined in the final phase of the Gothic period. This was because wealthy patrons started commissioning works from Paris and then Flanders instead. Competition from a strong French industry also overshadowed English ivory-carving. Some of the extremely rare surviving English medieval panel paintings, like the Westminster Retable and Wilton Diptych (the artist's nationality here is uncertain), are of the highest quality. Wall-paintings were very common in both churches and palaces, but very little survives now. There was an industry producing Nottingham alabaster reliefs. These were made in Nottingham, but also Burton-on-Trent, Coventry, and perhaps Lincoln and London. They ranged from commissioned altarpieces to single figures and story panels, which were exported across Europe. English monumental carving in stone and wood was often very high quality, and much of it survived the Reformation.

Literature, Drama, and Music

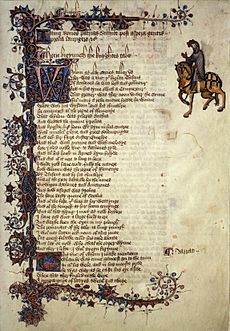

Poetry and stories written in French were popular after the Norman conquest. By the 12th century, some works on English history began to be written in French verse. Romantic poems about tournaments and courtly love became popular in Paris. This trend spread to England in the form of lays. Stories about the court of King Arthur were also popular, partly due to Henry II's interest. English continued to be used on a small scale to write local religious works and some poems in northern England. But most major works were produced in Latin or French. Among others, the Pearl Poet, John Gower, and William Langland created a unique English culture and art.

During Richard II's reign, there was a rise in the use of Middle English in poetry, sometimes called "Ricardian poetry." These works still copied French styles. However, the work of Geoffrey Chaucer from the 1370s, ending with the influential Canterbury Tales, was uniquely English in style. Important courtly poetry continued to be produced into the 15th century by Chaucer's followers. Thomas Malory put together older Arthurian tales to create Le Morte d'Arthur.

Music and singing were important in England during the medieval period. They were used in religious ceremonies, court events, and to accompany plays. Singing techniques called gymel were introduced in England in the 13th century. They were accompanied by instruments like the guitar, harp, pipes, and organ. Henry IV supported a wide range of music in England. His son Henry V brought back many influences from occupied France. Carols became an important type of music in the 15th century. Originally, these were songs sung during a dance with a strong chorus. The 15th-century form lost the dancing and added strong religious themes. Ballads were also popular from the late 14th century. These included the Ballad of Chevy Chase and others describing the activities of Robin Hood. Miracle plays were performed to teach the Bible in various places. By the late 14th century, these had expanded into local mystery plays. These were performed annually over several days, broken into different cycles of plays. A few have survived into the 21st century. Guilds competed to produce the best plays in each town, and performances often showed civic identity.

Architecture

During the 12th century, the Anglo-Norman style became richer and more decorative. Pointed arches from French architecture replaced the curved Romanesque designs. This style is called Early English Gothic and continued, with variations, throughout the rest of the Middle Ages. In the early 14th century, the Perpendicular Gothic style was created in England. It focused on vertical lines, huge windows, and soaring arches. Fine timber roofs in various styles, especially the hammerbeam, were built in many English buildings. In the 15th century, the focus of architecture shifted from cathedrals and monasteries to parish churches. These were often decorated with richly carved woodwork. In turn, these churches influenced the design of new chapels for existing cathedrals.

By the 14th century, grander houses and castles were sophisticated. They had expensive tiles, often featured murals and glass windows. These buildings were often designed as a set of apartments to allow more privacy. Fashionable brick began to be used in some parts of the country, copying French tastes. Architecture that looked like older defensive designs remained popular. Less is known about peasant houses during this period. However, many peasants seem to have lived in fairly large, timber-framed long-houses. The quality of these houses improved in the good years after the Black Death. They were often built by professional craftsmen.

Legacy

Popular Representations

The medieval period has been used in many forms of popular culture. William Shakespeare's plays about the lives of medieval kings have remained popular. They greatly influenced how people see figures like King John and Henry V. Other playwrights have since taken key medieval events, such as the death of Thomas Becket. They used these to explore current themes and issues. Medieval mystery plays continue to be performed in key English towns and cities. Filmmakers have drawn a lot from the medieval period, often taking themes from Shakespeare or the Robin Hood stories for inspiration.

Historical fiction set in England during the Middle Ages remains very popular. The 1980s and 1990s saw a particular growth in historical detective fiction. The period has also inspired fantasy writers, including J. R. R. Tolkien's stories of Middle-earth. English medieval music was revived from the 1950s. Choral and musical groups tried to accurately reproduce the original sounds. Medieval living history events were first held in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The period has inspired a large community of historical re-enactors. This is part of England's growing heritage industry.