Taxation in medieval England facts for kids

Taxes in medieval England were how kings and governments collected money. This money paid for royal expenses and running the country. In the time of the Anglo-Saxons, people mainly paid taxes on land. They also paid fees for trading goods and making coins. The most important tax later in the Anglo-Saxon period was the geld. This was a land tax that started in 1012. It helped pay for soldiers who were hired from other countries. After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, the geld continued until 1162. Later, taxes on personal belongings and income became more common.

Contents

How Taxes Started in England

Britannia was the southern part of Great Britain. It was a province of the Roman Empire until the Romans left around 400 AD. In 410, Emperor Honorius told the Britons they had to protect themselves. We don't know much about how Britain was governed or how it collected money after that. This changed when Augustine of Canterbury arrived in the Kingdom of Kent in 597.

Anglo-Saxon Taxes (597–1066)

The first clear mention of taxes in Anglo-Saxon England is in the laws of King Æthelberht of Kent. These laws said that fines from court cases went to the king. Other kings, like Wihtred of Kent, gave churches tax breaks. This shows that other taxes must have existed. King Ine of Wessex also had laws about taxes.

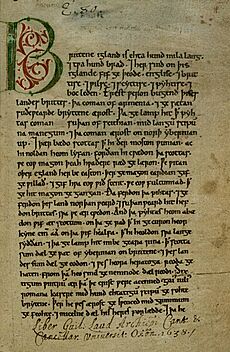

The writer Bede mentioned that land was divided into units called hides. King Ine's laws defined a hide as an area of land. This land could provide food and other goods for the king. A document from the 7th or 8th century, the Tribal Hidage, shows that much of Anglo-Saxon land was divided into hides. King Offa of Mercia collected tolls on trade. He also introduced silver coins, which made paying taxes easier.

The Hide and Common Burdens

In early Anglo-Saxon England, the hide was used to figure out how much food rent (called feorm) was owed. The size of a hide changed based on the land's value. Over time, the hide became the basis for all public duties. Landowners had three main duties:

- Provide soldiers for the army.

- Help build and fix forts.

- Help repair bridges.

Dealing with Vikings and the Danegeld

When Viking raiders became a big problem, Anglo-Saxon leaders raised taxes. These taxes were also based on how much land a person owned (their hidage). This tax was called the Danegeld. It was used to pay off the raiders instead of fighting them.

In the 9th century, Alfred the Great faced the Vikings. After winning the Battle of Edington in 878, he built a system of fortified towns called burhs. He also created a standing army and navy. To pay for this, Alfred needed a new tax system. This system is described in a document called the Burghal Hidage. It lists over thirty fortified places and the taxes (in hides) needed to keep them running.

Later, King Edgar improved the tax system. He regularly recalled all coins and had them reminted. The people who made the coins had to pay for new tools. All the money from this went to the king. Despite these changes, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that England paid a huge amount of money to Scandinavian attackers between 991 and 1012.

The Geld and Its End

In 1012, King Æthelred the Unready introduced the geld or heregeld (meaning "army tax"). This was an annual tax used to pay for hired soldiers for the army and navy. This stronger military was needed because King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark was invading England. Later, after Sweyn's son Cnut the Great conquered England, the geld continued. This tax was collected in a similar way to the Danegeld. It was also based on the number of hides a person owned. The amount owed from each hide could change.

In 1051, King Edward the Confessor stopped the heregeld. He saved money by selling off his navy. He gave the job of naval defense to the Cinque ports in exchange for special rights. However, the heregeld might have been brought back in 1052.

Norman and Angevin Taxes (1066–1216)

After the Normans took over, there was no clear difference between the king's personal money and the government's money. So, tax money mixed with other income to pay for both the king and the government. Under the Norman and Angevin kings, the government had four main ways to get money:

- Money from lands the king owned directly.

- Money from his rights as a feudal lord, like feudal aid or scutage.

- Taxes.

- Money from fines and other profits from justice.

By the time of King Henry I, most money went into the Exchequer, which was like England's Treasury. The first records of the Exchequer are from 1130. From King Henry II's reign, these records (called Pipe Rolls) show royal income and taxes. However, not all money went into the Exchequer. Some special taxes were not recorded there.

Types of Taxes in This Period

The main tax was still the geld, based on land. It was special in Europe because it applied to everyone, not just the king's direct tenants. It was still based on the hide, usually 2 shillings per hide. Sometimes, taxes were paid by doing services for the king, like Avera and Inward.

The geld only applied to free men who owned land. Serfs and slaves did not have to pay it. Some favored people or government officials were also exempt. The geld was not popular. Because more and more people were exempt, it brought in less money. We don't know if the geld was collected during King Stephen's reign because no financial records exist. But when King Henry II became king, the geld was collected again. After 1162, however, the geld was no longer collected.

New Taxes Emerge

A new type of tax started in 1166. It was not an annual tax. This was a tax on movable property (like goods) and income. The tax rate could change. For example, the Saladin tithe was set in 1188. It was meant to raise money for a crusade planned by King Henry II. This tax was 10% of all goods and income. Some things were exempt, like a knight's horse and armor. People who promised to go on the crusade with the king were also exempt.

In 1194, a new land tax called the carucage was introduced. This was partly to raise the huge amount of money needed to free King Richard I, who was held captive in Germany. Like the geld, it was based on land. The carucage was collected six times in total. But it brought in less money than other ways of raising funds. It was last collected in 1224. Also in 1194, a 25% tax was put on all personal property and income to help pay Richard's ransom. In other years, different rates were set, like the "thirteenth" in 1207.

Besides taxes on land and personal property, taxes on trade also began. In 1202, King John started a custom duty. This was a tax of one-fifteenth of the value of all goods coming into or leaving the country. However, these duties seemed to stop in 1206.

Plantagenet Taxes (1216–1360)

During King Henry III's reign, the king and government asked England's nobles for permission to collect taxes. This led to the start of the Parliament of England in 1254. The nobles advised the king to call knights from each area (shire) to help decide on new taxes. In the 1260s, men from towns were also included. This was the beginning of the House of Commons of England.

By the mid-13th century, the tax on movable property became standard. It was one-fifteenth for people in the countryside and one-tenth for those in towns. A new idea in 1334 was to set a total amount for each community. This replaced individual tax calculations.

In 1275, King Edward I brought back customs duties. He set a tax on each sack of wool and on a last of hides. In 1294, Edward added another tax called the maltolt on wool. This was on top of the existing customs duty. These taxes were removed in 1296. But in 1303, they were brought back, but only for non-English merchants. For the next 40 years, the maltolt caused arguments between the king and Parliament. In the end, the tax was kept at a lower rate, but Parliament's permission was needed to collect it.

Late Medieval Taxes (1360–1485)

The money from traditional taxes went down in later medieval England. So, the government tried different types of poll taxes (a tax on each person). In 1377, there was a flat-rate poll tax. In 1379, there was a graduated tax, meaning richer people paid more. By 1381, these unpopular taxes helped cause the Peasants' Revolt. Later attempts at income taxes in the 15th century did not raise enough money. Other taxes, like taxes on parishes, were also tried.

Images for kids

See also

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |