Peter Warlock facts for kids

Philip Arnold Heseltine (born October 30, 1894 – died December 17, 1930) was a British composer and music critic. He used the special name Peter Warlock for all his musical works. This name showed his interest in old, mysterious practices. Peter Warlock is most famous for writing songs and other music for voices. He was also known for his unusual and sometimes shocking way of life.

When he was a schoolboy at Eton College, Heseltine met the famous British composer Frederick Delius. They became very close friends. After not doing well in his studies at Oxford and London, Heseltine started writing about music. He also became very interested in folk songs and music from the Elizabethan era. His first serious musical pieces were written around 1915.

Later, in 1916, he met the Dutch composer Bernard van Dieren, who had a big and lasting impact on his music. He also got new ideas from spending a year in Ireland, where he studied Celtic culture and language. When he came back to England in 1918, Heseltine began writing songs in his own unique style. From 1920 to 1921, he was the editor of a music magazine called The Sackbut. He wrote most of his music in the 1920s, first when he lived in Wales and then in Eynsford in Kent.

Heseltine also wrote important articles about early music under his real name. He wrote a full book about Delius and helped with several other books. Towards the end of his life, Heseltine felt sad because he lost his creative ideas. He died in his London home in 1930.

Contents

Life of Peter Warlock

Early Life and Family

Childhood and Family Background

Philip Heseltine was born on October 30, 1894, at the Savoy Hotel in London. His parents were staying there at the time. His family was wealthy and had many connections to art and classical studies. Philip's father, Arnold Heseltine, was a lawyer. His mother, Bessie Mary Edith, was the daughter of a country doctor from Knighton, a town near the Welsh border. She was Arnold's second wife. Soon after Philip was born, the family moved to Chelsea. There, he went to a nearby kindergarten and started learning to play the piano.

In March 1897, Arnold Heseltine died suddenly when he was 45 years old. Six years later, Bessie married Walter Buckley Jones, a Welsh landowner and local judge. They moved to Jones's estate, Cefn Bryntalch, in Llandyssil, near Montgomery. However, the London house was kept. Young Philip was proud of his Welsh background. He kept a strong interest in Celtic culture throughout his life. He later lived in Wales during one of his most creative periods.

In 1903, Heseltine started at Stone House Preparatory School in Broadstairs. He was very smart and won many awards. In January 1908, he heard a piece called Lebenstanz by Frederick Delius at a concert in the Royal Albert Hall. He didn't think much of the music at first. But then he found out that his uncle, Arthur Joseph Heseltine (called "Joe"), an artist, lived near Delius's home in France. Philip used this connection to get Delius's autograph for his music teacher at Stone House.

Eton and Meeting Delius

Heseltine left Stone House in the summer of 1908 and started at Eton College that autumn. His biographer, Ian Parrott, wrote that Heseltine hated Eton. He disliked the loud singing of Victorian hymns in the all-male chapel. He also didn't like other parts of school life, such as the military training. He found comfort in music. Because of his uncle's connection, he became very interested in Delius. He also found a good friend in Edward Mason, an Eton music teacher and cellist who liked Delius. Heseltine borrowed a copy of Delius's Sea Drift from Mason. He thought it was "heavenly" and soon asked his mother for money to buy more of Delius's music. According to Cecil Gray, Heseltine's first biographer, Heseltine "did not rest until he had procured every work of Delius which was then accessible."

In June 1911, Heseltine learned that Thomas Beecham would conduct an all-Delius concert in London. Delius himself would be there, and his Songs of Sunset would be performed for the first time. Colin Taylor, a kind piano tutor at Eton, helped Heseltine get permission to attend the concert. Before this, his mother had arranged to meet Delius at her London home. Because of this, Heseltine was introduced to the composer during the concert break. The next day, he wrote Delius a long letter, saying how much he enjoyed the music. He told his mother that "Friday evening was the most perfectly happy evening I have ever spent, and I shall never forget it." Delius became the first strong influence on Heseltine's music. Even though his admiration changed later, their friendship lasted for most of Heseltine's life.

Studies and Early Career

Cologne, Oxford, and London

By the summer of 1911, Heseltine was tired of Eton. He asked his mother if he could live abroad for a while. His mother wanted him to go to university and then work in the city or for the government. But she agreed, as long as he would continue his education later. In October 1911, he went to Cologne to learn German and study piano at the conservatory. In Cologne, Heseltine wrote his first few songs. Like all his early works, they sounded very much like Delius's music. His piano studies did not go well, but Heseltine learned more about music by going to concerts and operas. He also tried writing for newspapers, publishing an article about an old Welsh train line.

In March 1912, Heseltine returned to London. He hired a tutor to prepare for his university entrance exams. He spent time with Delius at a music festival that summer. He also published his first music review, an article about Arnold Schoenberg, in September 1912. Even though his mother wanted him to go to university and he had no formal music training, he hoped to have a career in music. He asked Delius for advice. Delius told him that if he was determined, he should follow his instincts. Beecham, who knew both men, later criticized this advice. He felt Heseltine was too young and unsettled. In the end, Heseltine agreed to his mother's wishes. He passed the exams and was accepted to study classics at Christ Church, Oxford. He started there in October 1913.

A friend at Christ Church described the 19-year-old Heseltine as tall, fit, with bright blue eyes. Although he was popular, he soon became sad and unhappy with life at Oxford. In April 1914, he spent part of his Easter break with Delius in France. He helped Delius with his music, including an English version of the words for Delius's opera Fennimore and Gerda. He did not go back to Oxford after the summer break in 1914. With his mother's permission, he moved to Bloomsbury in London. He enrolled at University College London to study language, literature, and philosophy. In his free time, he led a small amateur orchestra in Windsor. However, his time as a student in London was short. In February 1915, he got a job as a music critic for the Daily Mail. He quickly left his university studies to start this new career.

A Time of Change

Music Critic and New Friends

During his four months at the Daily Mail, Heseltine wrote about 30 articles. These were mostly short reports on music events. His first article, in February 1915, praised a performance of Delius's Piano Concerto. He called Delius "the greatest composer England has produced for two centuries." He also wrote for other publications. A long article called "Some notes on Delius and his Music" appeared in The Musical Times in March 1915. In it, Heseltine said that Delius's music must be felt deeply. Heseltine left the Daily Mail in June because he was frustrated that the paper often cut out his more critical opinions. Without a job, he spent his days at the British Museum, studying and editing old Elizabethan music.

Heseltine spent much of the summer of 1915 in a rented cottage. In November 1915, his life became more active when he met D. H. Lawrence. In late December, he followed the Lawrences to Cornwall.

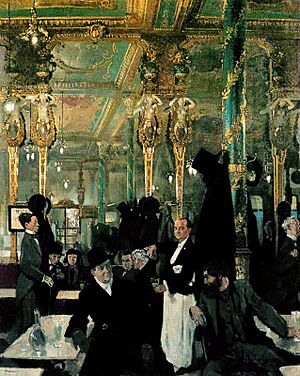

In February 1916, Heseltine returned to London. The Café Royal became the main social spot for Heseltine. There, he met Cecil Gray, a young Scottish composer. The two decided to share a studio in Battersea. They planned many things, including a new music magazine and a season of operas and concerts in London.

A very important event for Heseltine's music happened in late 1916. He was introduced to the Dutch composer Bernard van Dieren. This friendship greatly influenced Heseltine, who continued to promote Van Dieren's music for the rest of his life. In November 1916, Heseltine used the name "Peter Warlock" for the first time. This was in an article about Eugene Aynsley Goossens's music.

On December 22, 1916, he married his girlfriend, Minnie Lucie Channing, an artist's model. She was known as "Puma."

Time in Ireland

By April 1917, Heseltine was again tired of London. He went back to Cornwall. By the summer of 1917, his military exemption was being reviewed. To avoid being drafted, he moved to Ireland in August 1917, taking Puma with him.

In Ireland, Heseltine studied early music and became very interested in Celtic languages. He spent two months on a remote island where only Irish was spoken.

On May 12, 1918, Heseltine gave a popular lecture called "What Music Is" at Dublin's Abbey Theatre. It included music by Bartók and Van Dieren. Heseltine's support for Van Dieren's music led to a strong disagreement with a music publisher in August 1918. This argument made Heseltine's own creative ideas flow. In his last two weeks in Ireland, he wrote ten songs. Later critics have said these are among his best works.

Journalism and The Sackbut Magazine

When Heseltine returned to London in August 1918, he sent seven of his new songs to a publisher. Because of his recent disagreement, Heseltine sent these songs as "Peter Warlock." They were published under this name. From then on, he used "Peter Warlock" for all his music and his own name for his writing about music. Around this time, the composer Charles Wilfred Orr remembered Heseltine as a "tall fair youth" who tried to convince Delius about Van Dieren's piano music. Orr was especially impressed by Heseltine's whistling, which he said was "flute-like."

For the next few years, Heseltine focused on writing about music. In May 1919, he gave a speech called "The Modern Spirit in Music." Much of his writing was strong and sometimes caused arguments. He made comments about music critics that offended some older writers. He also wrote articles in The Musical Times that caused debate.

In a letter from July 17, 1919, Delius advised Heseltine to focus on either writing or composing. By this time, Heseltine's private opinions about Delius's music were becoming more critical. However, in public, he continued to praise Delius.

Heseltine had long wanted to start a music magazine. In April 1920, a publisher decided to replace his old magazine with a new one called The Sackbut. He invited Heseltine to be the editor. Heseltine edited nine issues, using a strong and often controversial style. The Sackbut also organized concerts. However, the publisher stopped his financial support after five issues. Heseltine tried to run it himself for several months. In September 1921, the magazine was taken over by another publisher, who replaced Heseltine as editor.

Creative Years in Wales

Without a regular income, Heseltine returned to Cefn Bryntalch in the autumn of 1921. This became his home for the next three years. He found the place good for creative work. He told Gray that "Wild Wales holds an enchantment for me stronger than wine or woman." His years in Wales were filled with intense musical and writing activity. Some of Heseltine's most famous music, including the song-cycles Lilligay and The Curlew, were finished there. He also wrote many songs, choral pieces, and a string serenade for Delius's 60th birthday in 1922. Heseltine also edited and copied a lot of old English music. His growing fame as a composer was shown when The Curlew was chosen to represent British music at the 1924 Salzburg Festival.

Heseltine's main writing project during this time was a book about Delius. It was the first full book about the composer and was considered the best for many years. When it was reissued in 1952, it was called "a work of art, a charming and penetrating study of a musical poet's mind." Heseltine also worked with Gray on a study of the 16th-century Italian composer Carlo Gesualdo. However, disagreements between the two men delayed the book's publication until 1926.

While visiting Budapest in April 1921, Heseltine became friends with the Hungarian composer and pianist Béla Bartók. When Bartók visited Wales in March 1922 for a concert, he stayed for a few days at Cefn Bryntalch. Heseltine continued to promote Bartók's music, but they did not meet again after the Wales visit. Heseltine's on-again, off-again friendship with Lawrence ended after a book was published in 1922 that seemed to describe Heseltine and Puma in an unflattering way. Heseltine started legal action, but eventually settled with the publishers. Puma had left Heseltine's life by this time. She had lived for a while with their young child at Cefn Bryntalch. There was no return to married life, and she left Heseltine sometime in 1922.

In September and October 1923, Heseltine traveled with his fellow composer Ernest John Moeran to eastern England. They were looking for original folk music. Later that year, he and Gray visited Delius in France. In June 1924, Heseltine left Cefn Bryntalch. He lived briefly in a flat in Chelsea, where he held many parties. After spending Christmas 1924 in Majorca, he rented a cottage in the Kent village of Eynsford.

Life in Eynsford

In Eynsford, Heseltine lived in an artistic household with Moeran as his housemate. Many artists, musicians, and friends came and went. Moeran had studied music and collected folk music. He also admired Delius. Although they had much in common, he and Heseltine rarely worked together. They did write one song together, "Maltworms." Other people who lived in the Eynsford house were Barbara Peache, Heseltine's long-term girlfriend, and Hal Collins, a Māori from New Zealand who helped around the house. Peache was described as a "quiet, attractive girl." Collins was a talented graphic designer and sometimes helped Heseltine with music. Other visitors included composers William Walton and Constant Lambert, and artist Nina Hamnett.

Heseltine continued to copy old music, write articles, and finish the book on Gesualdo. He tried to bring attention back to a forgotten Elizabethan composer, Thomas Whythorne. He also wrote a general study of Elizabethan music called The English Ayre.

In January 1927, Heseltine's string serenade was recorded by John Barbirolli. A year later, the song "Captain Stratton's Fancy" was recorded. These were the only recordings of Heseltine's music released during his lifetime. By the summer of 1928, his way of life had caused serious money problems. In October, he had to leave the cottage in Eynsford and returned to Cefn Bryntalch.

Final Years and Passing

By November 1928, Heseltine was tired of Cefn Bryntalch and returned to London. He looked for jobs reviewing concerts and cataloging music, but without much success.

In early 1929, Heseltine received two offers from Beecham that gave him a new sense of purpose. Beecham invited Heseltine to edit a music journal. Beecham also asked Heseltine to help organize a festival to honor Delius in October 1929. Even though Heseltine's excitement for Delius's music had lessened, he accepted the job. He traveled to France to find forgotten Delius compositions for the festival. He was happy to find Cynara, a piece for voice and orchestra, which had been set aside since 1907. For the festival, Heseltine wrote many of the program notes for the concerts and a short biography of Delius. Delius's wife said that Heseltine was "the soul of the thing" next to Beecham.

At a Promenade Concert in August 1929, Heseltine conducted a performance of the Capriol Suite. This was the only time he conducted in public. Heseltine edited three issues of the journal. But in January 1930, Beecham closed the project, and Heseltine was out of work again. His attempt to get funding for a performance of Van Dieren's opera also failed.

The last summer of Heseltine's life was filled with sadness and little activity. In July 1930, two weeks spent with a friend brought a brief return of his creativity. Heseltine composed "The Fox" and "The Fairest May." These were his last original compositions.

Death

In September 1930, Heseltine moved with Barbara Peache into a flat in Chelsea. Without new creative ideas, he worked at the British Museum. On the evening of December 16, Heseltine met Van Dieren and his wife. They left his flat around 12:15 a.m. Neighbors later heard sounds from the flat in the early morning. When Peache returned early on December 17, she found the doors and windows locked and smelled gas. The police entered the flat and found Heseltine unconscious. He was declared dead shortly after.

Philip Heseltine was buried next to his father in Godalming cemetery on December 20, 1930. In February 1931, a memorial concert of his music was held. A second concert took place the following December.

In 2011, the art critic Brian Sewell wrote his memories. He claimed he was Heseltine's son, born in July 1931, seven months after the composer's death. Sewell's mother was Mary Jessica Perkins. Sewell did not know who his father was until 1986.

Legacy and Impact

Heseltine's music includes about 150 songs, mostly for a single voice and piano. He also wrote pieces for choirs and some instrumental works. Music historian Stephen Banfield described his songs as "polished gems of English art song." He said they were intense, consistent, and excellent. According to Delius's biographer Christopher Palmer, Heseltine influenced other composers like Moeran and Walton. He helped them connect with Delius's musical style.

Critical Views of His Music

Heseltine's music was generally well-liked by the public and critics. His first works to get attention were three songs published in 1918. One critic called them "first rate." In 1922, a short song cycle was praised for its "rattling good tunes." Ralph Vaughan Williams was very happy with how his Three Carols were received in 1923. In early 1925, the BBC broadcast a performance of his Serenade for string orchestra. This showed that the music world was starting to take Warlock seriously. Heseltine himself noted the warm reaction from the audience when he conducted the Capriol Suite in 1929.

After Heseltine's death, people spoke highly of his music. One critic said some of his choral pieces were "among the finest music written for massed voices by a modern Englishman." Constant Lambert called him "one of the greatest song-writers that music has ever known." Another said his music was "a national treasure." In later years, his standing as a composer lessened. However, when the Peter Warlock Society was created in 1963, interest in his music began to grow again. While some of Warlock's music might be considered less important, many of his works are of the highest quality. They are often thrilling, passionate, and sometimes very new and different.

Writings

Besides his many articles about music, Heseltine wrote or helped create 10 books or long pamphlets:

- Frederick Delius (1923). John Lane, London

- Thomas Whythorne: An unknown Elizabethan composer (1925). Oxford University Press, London (pamphlet)

- (Editor) Songs of the Gardens (1925). Nonesuch Press, London (a collection of 18th-century popular songs)

- (Preface) Orchésography by Thoinot Arbeau, tr. C.W. Beaumont (1925). Beaumont, London

- The English Ayre (1926). Oxford University Press, London

- (with Cecil Gray) Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa: Musician and Murderer (1926). Kegan Paul, London

- Miniature Essays: E.J. Moeran (1926). J.& W. Chester, London (pamphlet, published without a name)

- (with Jack Lindsay) Loving Mad Tom: Bedlamite verses of the 16th and 17th centuries (1927). Fanfrolico Press, London (music copied by Peter Warlock)

- (Editor, joint with Jack Lindsay) The Metamorphosis of Ajax (1927). Fanfrolico Press, London

- (Editor under the name "Rab Noolas") Merry-Go-Down, A Gallery of Gorgeous Drunkards through the ages (1929) (a collection of writings)

At the time of his death, Heseltine was planning to write a book about John Dowland.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Peter Warlock para niños

In Spanish: Peter Warlock para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |