John Barbirolli facts for kids

Sir John Barbirolli CH (born Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 1899 – 29 July 1970) was a famous British conductor and cellist. He is best known for leading the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester. He helped save this orchestra in 1943 and conducted it for the rest of his life.

Earlier in his career, he took over from Arturo Toscanini as the music director of the New York Philharmonic. He held this important job from 1936 to 1943. He also led the Houston Symphony from 1961 to 1967. Barbirolli was a guest conductor for many other top orchestras around the world. These included the BBC Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia, Berlin Philharmonic, and Vienna Philharmonic. He made many recordings with these orchestras.

Born in London, Barbirolli came from a family of musicians. His parents were Italian and French. He started as a cellist but soon got the chance to conduct. He began conducting opera in 1926 with the British National Opera Company. Later, he worked with the touring company of Covent Garden.

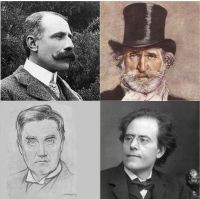

When he became the conductor of the Hallé, he had less time for opera. But in the 1950s, he conducted successful operas by Verdi, Wagner, Gluck, and Puccini at Covent Garden. He was even asked to become the permanent music director there, but he said no. Later in his career, he recorded several operas. His 1967 recording of Puccini's Madama Butterfly for EMI is very well known.

Barbirolli was especially famous for his performances of music by English composers. These included Elgar, Delius, and Vaughan Williams. People also admired his interpretations of other late Romantic composers. These were artists like Mahler and Sibelius. He also conducted earlier classical composers, such as Schubert.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Musical Start

Giovanni Battista Barbirolli was born in London on 2 December 1899. He was the second child of an Italian father and a French mother. He was a British citizen from birth. He considered himself a "Cockney" because he was born within the sound of Bow Bells. His father, Lorenzo Barbirolli, was a violinist from Venice. He had settled in London with his wife, Louise Marie. Both Lorenzo and his father had played in the orchestra at La Scala in Milan. They even performed in the first show of the opera Otello in 1887. In London, they played in theatre orchestras in the West End.

Young Barbirolli started playing the violin at age four. But he soon switched to the cello. He later said his grandfather encouraged this change. His grandfather was tired of him wandering around while practicing the violin. So, he bought him a small cello to keep him from "getting in everybody's way."

Barbirolli went to St. Clement Danes Grammar School. From 1910, he also had a scholarship at Trinity College of Music. As a student there, he played a cello concerto in the Queen's Hall in 1911. This was his first public concert.

The next year, he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music. He studied there from 1912 to 1916. He learned about harmony, counterpoint, and music theory. He also studied the cello with Herbert Walenn. In 1914, he won a prize for playing in an ensemble. In 1916, The Musical Times newspaper praised him as an "excellent young 'cello player."

The head of the Academy, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, didn't like modern music. He had forbidden students from playing the chamber music of Ravel. Barbirolli loved modern music. So, he and three friends secretly practiced Ravel's String Quartet in a men's restroom at the Academy!

From 1916 to 1918, Barbirolli worked as a freelance cellist in London. He played in the Queen's Hall Orchestra, which had a huge number of pieces to play. He also played in opera orchestras and for recitals. He even played in theatres, cinemas, hotels, and dance halls. During the last year of World War I, Barbirolli joined the army. He became a lance-corporal in the Suffolk Regiment. Here, he got his first chance to conduct. He led an orchestra of volunteers.

While in the army, Barbirolli changed his first name to John. This was for simplicity. He said, "The sergeant-major had great difficulty in reading my name on the roll-call. 'Who is this Guy Vanni?' he used to ask. So I chose John." After the war, he went back to using his original name until 1922.

After the war, Barbirolli continued his cello career. He played in the first performance of Edward Elgar's Cello Concerto in 1919. He was part of the London Symphony Orchestra. A year later, he was the solo cellist in another performance of the concerto. He also joined two new string quartets.

First Steps as a Conductor

Barbirolli really wanted to conduct. In 1924, he helped create the Guild of Singers and Players Chamber Orchestra. In 1926, he was asked to conduct a new group at the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea. It was first called the "Chenil Chamber Orchestra" and then "John Barbirolli's Chamber Orchestra."

Barbirolli's concerts impressed Frederic Austin, who directed the British National Opera Company (BNOC). In the same year, Austin invited him to conduct some shows. Barbirolli had never conducted a choir or a large orchestra before. But he was confident enough to accept. He made his opera debut conducting Gounod's Roméo et Juliette in Newcastle. Days later, he conducted Aida and Madama Butterfly. He conducted the BNOC often for the next two years. He made his debut at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, with Madama Butterfly in 1928.

In 1929, the BNOC had money problems and closed down. The Covent Garden management started a touring company to fill the gap. They made Barbirolli its music director and conductor. He conducted many operas on their first tour. These included Die Meistersinger, Lohengrin, La bohème, and Madama Butterfly. He also conducted the first English performances of Turandot. In later tours, he conducted more German operas.

While working with the opera companies, Barbirolli also conducted concerts. In 1927, he filled in for Sir Thomas Beecham at short notice. He conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in Elgar's Symphony No. 2. Elgar himself thanked him. Barbirolli also received praise from Pablo Casals, a famous cellist.

In 1932, the Hallé Orchestra announced that its regular conductor, Hamilton Harty, would be away. Barbirolli was one of four guest conductors chosen to lead the orchestra. The others were Elgar, Beecham, and Pierre Monteux. Barbirolli's programs included music by many different composers. In June 1932, Barbirolli married singer Marjorie Parry. In 1933, he was invited to conduct the Scottish Orchestra. He stayed with them for three seasons, improving their playing and programs. Even though he was becoming well-known in Britain, Barbirolli was not famous internationally. So, many people were surprised in 1936 when he was asked to conduct the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. He was replacing the legendary Arturo Toscanini.

Leading the New York Philharmonic

In 1936, the New York Philharmonic faced a challenge. Toscanini had left. Wilhelm Furtwängler had agreed to take the job. But some people in New York didn't want him because he lived and worked in Germany under the Nazi government. After protests, he couldn't take the position. So, the orchestra invited five guest conductors to share the season. Barbirolli was given the first ten weeks, which included 26 concerts.

Barbirolli's first concert in New York was on 5 November 1936. The program included pieces by Berlioz and Arnold Bax. It also featured symphonies by Mozart and Brahms. During his ten weeks, he played several new American pieces. The musicians told the Philharmonic management that they would be happy for Barbirolli to get a permanent job. So, he was invited to become the Music Director and Permanent Conductor for three years, starting in the 1937–38 season.

At the same time, Barbirolli's personal life changed. His marriage to Marjorie Parry ended in divorce in 1938. In 1939, Barbirolli married the British oboist Evelyn Rothwell. Their marriage lasted for the rest of his life.

One important part of Barbirolli's time in New York was his regular programming of modern works. He conducted the first performances of Walton's Façade Suite and Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem and Violin Concerto. He also introduced pieces by other composers. These new works were not extremely experimental, but they still upset some of the older audience members. Ticket sales went down after an initial rise.

Barbirolli also faced criticism from some New York newspapers. Influential critic Olin Downes was against Barbirolli's appointment from the start. He believed an American conductor should have been chosen. Downes and composer Virgil Thomson often wrote negative things about Barbirolli. They compared him unfavorably to Toscanini. Despite this, the orchestra management renewed Barbirolli's contract in 1940. In 1942, he was offered fewer concerts for the next season. He also received an offer from the Los Angeles Philharmonic. But he decided to return to England.

Barbirolli had two main reasons for leaving. First, the Musicians Union in New York said that all musicians and conductors had to become members. They also said conductors had to become American citizens. Barbirolli couldn't do that during the war. Second, he felt strongly that he was needed in England.

He returned to New York to finish his contract. Soon after, he received an urgent request from the Hallé Orchestra. The orchestra was in danger of closing down because it didn't have enough players. Barbirolli quickly agreed to help them.

Saving the Hallé Orchestra

In 1943, Barbirolli traveled across the Atlantic Ocean again. He avoided death by chance. He changed flights with actor Leslie Howard, who wanted to delay his flight. Barbirolli's plane landed safely. Howard's plane was shot down.

In Manchester, Barbirolli immediately started to rebuild the Hallé. The orchestra had only about 30 players. Most young musicians were serving in the armed forces. Also, the orchestra's management had ended an agreement where many players also worked for the BBC Northern Orchestra. The Hallé decided it needed to become a full-time orchestra, like the Liverpool Philharmonic. Only four players who worked for both the Hallé and the BBC chose to stay with the Hallé.

The Times newspaper later wrote about Barbirolli's first actions. "In a couple of months of endless auditions, he rebuilt the Hallé. He accepted any good player, no matter their musical background." He found a schoolboy as the first flute player and a schoolmistress as a horn player. He also found brass players from local bands. The Musical Times noted that the orchestra's string section immediately sounded amazing. Barbirolli was known for training orchestras. After he died, one former player said, "If you wanted orchestral experience you'd be set for life, starting in the Hallé with John Barbirolli."

Barbirolli turned down offers to lead more famous and higher-paying orchestras. Soon after joining the Hallé, he received an offer to lead the London Symphony Orchestra. In the early 1950s, the BBC tried to hire him for the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Also, the head of the Royal Opera House, David Webster, wanted him to be their music director. Barbirolli conducted six operas for Webster between 1951 and 1953. But he refused to leave the Hallé. His biographer Charles Reid wrote that his "Manchester kingdom" was a true kingdom. He could choose his own programs and conduct only what he loved.

However, in 1958, after building up the orchestra and touring a lot, he arranged a lighter schedule. This allowed him more time to be a guest conductor with other orchestras. He also performed at the Vienna State Opera and the Rome Opera House. In 1960, he became the chief conductor of the Houston Symphony in Texas. He held this job until 1967, conducting for 12 weeks each year. In 1961, he began working regularly with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. This continued for the rest of his life.

From 1953 onwards, Barbirolli and the Hallé regularly played at the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts in London. Besides major classical works, they gave an annual concert of music by Viennese composers. These concerts, like Sir Malcolm Sargent's Gilbert and Sullivan nights, became very popular. In 1958, Barbirolli and the Hallé even recreated Charles Hallé's first concert from 1858.

Barbirolli's interest in new music lessened after the war. But he and the Hallé still played regularly at the Cheltenham Festival. There, he performed new works by British composers. More and more, Barbirolli focused on his main repertoire. This included standard classical symphonies, English composers, and late-romantic music, especially Mahler. In the 1960s, he toured internationally with the Philharmonia (South America, 1963), BBC Symphony Orchestra (Eastern Europe, 1967), and the Hallé (South America and West Indies, 1968). He was always disappointed that he never got to take the Hallé on a tour of the United States.

In 1968, after 25 years with the Hallé, Barbirolli stepped down as the main conductor. No one was chosen to replace him while he was alive. He was named the orchestra's Conductor Laureate. He conducted the Hallé less often but still took them on another European tour in 1968. In his last years, he sometimes focused too much on small details instead of the whole piece. His friend, critic Neville Cardus, wrote privately in 1969 that Barbirolli seemed to "love a single phrase" so much that he would "linger over it," losing the overall flow.

His last year, 1970, was difficult due to heart problems. He collapsed several times. His last two concerts were with the Hallé at the 1970 King's Lynn Festival. He gave "inspired" performances of Elgar's Symphony No. 1 and Sea Pictures. The last piece he conducted in public was Beethoven's Symphony No. 7. This was just before his death. On the day he died, 29 July 1970, he spent hours rehearsing the New Philharmonia Orchestra for a tour of Japan.

Barbirolli died at his London home from a heart attack. He was 70 years old. He had planned to conduct Otello at the Royal Opera House and record more operas for EMI.

Awards and Tributes

Sir John Barbirolli received many honors. He was made a British knight in 1949 and a Companion of Honour in 1969. He also received awards from Finland, Italy, and France. Musical groups gave him awards too, like the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1950. He was also given an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the National University of Ireland in 1952.

There are memorials to Barbirolli in Manchester and London. Barbirolli Square in Manchester is named after him. It has a sculpture of him created in 2000. The Bridgewater Hall, home of the Hallé Orchestra, has a Barbirolli Room. At his old school, St Clement Danes, the main hall is named in his honor. A special blue plaque was placed on the Bloomsbury Park Hotel in London in 1993. This marks his birthplace.

After his death, the Sir John Barbirolli Memorial Foundation was created. It helps young musicians buy instruments. In 1972, the Barbirolli Society was formed. Its main goal is to keep releasing Barbirolli's recorded performances. In April 2012, he was voted into the first Gramophone "Hall of Fame."

Music He Loved and Recorded

Barbirolli is remembered for his amazing performances of music by Elgar, Vaughan Williams, and Mahler. He also excelled at music by Schubert, Beethoven, Sibelius, Verdi, and Puccini. He was a strong supporter of new music by British composers. Vaughan Williams even dedicated his Eighth Symphony to Barbirolli. He nicknamed him "Glorious John."

Barbirolli didn't just conduct serious classical music. He also enjoyed lighter pieces. Music critic Richard Osborne said that if all of Barbirolli's recordings were lost except for Lehár's Gold and Silver Waltz, it would still show what a great conductor he was.

Barbirolli's range of music was not as wide as some other conductors. This was because he spent a lot of time preparing every piece he conducted. His friend Sir Adrian Boult admired him but also teased him for being so careful. Barbirolli took his work very seriously. For example, he spent hours carefully marking all the string parts for Mahler's symphonies. His first performance of Mahler's Ninth Symphony took almost 50 hours of rehearsal!

Early Recordings

Barbirolli started recording very early in his career. As a young cellist, he made four records in 1911. He also recorded chamber music in 1925 and 1926. As a conductor, he began recording in 1927. One of his early recordings was the first ever of Elgar's Introduction and Allegro for Strings. When Elgar heard it, he said, "I'd never realised it was such a big work."

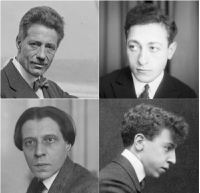

In 1928, Barbirolli began his long partnership with the His Master's Voice (HMV) record label. An HMV colleague called Barbirolli "a treasure." This was because he could work well with many famous soloists like Chaliapin, Heifetz, Artur Rubinstein, Fritz Kreisler, and Pablo Casals.

Many of Barbirolli's pre-war recordings were of concertos. He was so good at accompanying soloists that it sometimes overshadowed his skills as a symphony conductor. This made him sensitive about it later. For many years after the war, he didn't want to accompany anyone in the recording studio. His early HMV records include concertos by Brahms, Bruch, Chopin, Dvořák, and others. Since the 1990s, recordings of Barbirolli's early New York concerts have been released on CD. These show that the orchestra played wonderfully for him.

Recordings After 1943

Within six months of returning to Britain in 1943, Barbirolli restarted his contract with HMV. He conducted the Hallé in symphonies by Bax and Vaughan Williams. He also recorded works by many other composers. In 1955, he signed with Pye Records. With them, he and the Hallé made many recordings, including their first stereo recordings. They recorded symphonies by Beethoven, Dvořák, Elgar, Mozart, and Mahler, among others.

In 1962, HMV convinced Barbirolli to return. With the Hallé, he recorded a full set of Sibelius symphonies. He also recorded Elgar's Second Symphony, Falstaff, and The Dream of Gerontius. With other orchestras, Barbirolli recorded a wide range of his favorite music. Many of these recordings are still available today. His Elgar recordings include the Cello Concerto with Jacqueline du Pré and Sea Pictures with Janet Baker. His Mahler recordings include the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies. With the Vienna Philharmonic, he recorded all of Brahms's symphonies.

He also made three opera recordings for HMV. These were Purcell's Dido and Aeneas (1966), Verdi's Otello (1969), and Madama Butterfly (1967). The Madama Butterfly recording was so successful that the head of the Rome Opera invited him to conduct "any opera you care to name with as much rehearsal as you wish." HMV had planned to record Die Meistersinger with Barbirolli in Dresden in 1970. But after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, he refused to conduct in Soviet-controlled countries.

Images for kids

-

Royal Academy of Music, London

-

Carnegie Hall, New York, where Barbirolli conducted from 1936 to 1943

-

Elgar (top l.), Verdi, (top r.) Vaughan Williams (lower l.) and Mahler, whose music was central to Barbirolli's repertoire

-

Fritz Kreisler (top l.), Jascha Heifetz (top r.), Alfred Cortot (lower l.) and Arthur Rubinstein, whom Barbirolli accompanied in his early HMV recordings

See also

In Spanish: John Barbirolli para niños

In Spanish: John Barbirolli para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |