Thomas Beecham facts for kids

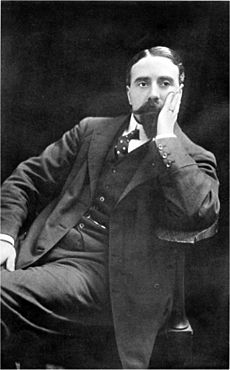

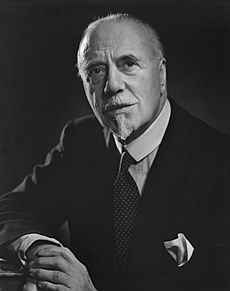

Sir Thomas Beecham, born on April 29, 1879, was a famous English conductor and someone who organized many concerts and operas. He is best known for working with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He also worked closely with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and The Hallé orchestras. From the early 1900s until he passed away in 1961, Beecham was a very important person in British music. The BBC even called him Britain's first international conductor.

Beecham came from a very rich family who owned a company that made medicines. He started his conducting career in 1899. He used his family's money to put on opera shows from the 1910s until World War II began. He staged seasons at famous places like Covent Garden and Drury Lane. He brought in international stars, used his own orchestra, and performed many different operas. Some of the works he introduced to England included operas by Richard Strauss like Elektra and Salome, and three operas by Frederick Delius.

Along with his younger friend Malcolm Sargent, Beecham started the London Philharmonic Orchestra. He conducted its first concert in 1932. In the 1940s, he spent three years in the United States, where he was the music director for the Seattle Symphony and conducted at the Metropolitan Opera. After returning to Britain, he founded the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in 1946 and led it until his death in 1961.

Beecham liked many different kinds of music. He sometimes preferred less famous composers over very well-known ones. He was especially good at performing works by composers like Delius and Berlioz, whose music wasn't very popular in Britain until Beecham supported them. Other composers whose music he often conducted included Haydn, Schubert, Sibelius, and his favorite composer, Mozart.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Thomas Beecham was born in St Helens, England, in a house next to the Beecham's Pills factory. This factory was started by his grandfather, also named Thomas Beecham. His parents were Joseph Beecham and Josephine Burnett. In 1885, as the family business grew, Joseph Beecham moved his family to a big house near Liverpool. Their old home was torn down to make the pill factory bigger.

Beecham went to Rossall School from 1892 to 1897. He wanted to study music in Germany, but his father said no. Instead, Beecham went to Wadham College, Oxford to study ancient Greek and Roman literature. He didn't like university life and got his father's permission to leave Oxford in 1898. He then studied how to compose music with different teachers in Liverpool, London, and Paris. He learned to conduct by himself.

First Orchestras and Opera Work

Beecham first conducted in public in St. Helens in October 1899. He led a group of local musicians and players from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and the Hallé orchestras. A month later, he filled in for the famous conductor Hans Richter at a concert. This concert was to celebrate his father becoming the mayor of St Helens. Around this time, Joseph Beecham had a serious disagreement with his wife, which led to family problems. Thomas and his older sister Emily helped their mother and made sure their father paid her money each year. Because of this, Joseph removed Thomas and Emily from his will. Beecham and his father did not speak for ten years.

Beecham's first professional conducting job was in 1902. He conducted The Bohemian Girl for an opera company in London. He was an assistant conductor for a tour and also conducted four other operas, including Carmen. Beecham also tried composing music in these early years, but he wasn't happy with his own pieces, so he focused on conducting instead.

In 1906, Beecham was asked to conduct the New Symphony Orchestra, a new group of 46 musicians, in London. Throughout his career, Beecham often chose to perform music he liked, even if it wasn't popular with the audience. In his early talks with this new orchestra, he suggested works by many composers that were barely known. During this time, Beecham first heard the music of Frederick Delius. He loved it immediately and became very connected to Delius's music for the rest of his life.

Beecham soon realized that to compete with other London orchestras, his group needed to be bigger and play in larger halls. For two years, starting in October 1907, Beecham and the larger New Symphony Orchestra gave concerts. He didn't worry much about selling tickets. His concerts often featured unusual pieces that didn't attract many people.

In 1908, Beecham and the New Symphony Orchestra stopped working together. They disagreed about who should control the artistic choices and about musicians sending substitutes to rehearsals or concerts. Beecham, like Henry Wood before him, banned this "deputy system."

In 1909, Beecham started the Beecham Symphony Orchestra. He didn't try to take musicians from other famous orchestras. Instead, he hired young musicians from theater bands, local music groups, hotels, and music schools. The orchestra was very young, with an average age of 25. Many of these young players later became famous musicians.

Because Beecham often chose music that didn't attract large audiences, his concerts usually lost money. Since he wasn't speaking to his father between 1899 and 1909, he had limited access to his family's wealth. He received some money from his grandfather's will and his mother helped pay for some concerts. But it wasn't until he and his father made up in 1909 that Beecham could use the family money to support opera.

1910–1920: Opera Seasons

From 1910, with his father's financial help, Beecham was able to put on opera seasons at Covent Garden and other theaters. In those days, star singers were seen as the most important part of an opera, and conductors were less noticed. Between 1910 and 1939, Beecham helped change this, making the conductor more important.

In 1910, Beecham conducted or was in charge of 190 performances at Covent Garden and Her Majesty's Theatre. He put on 34 different operas, most of which were new to London or hardly known there. Beecham later admitted that in his early years, the operas he chose were too unusual to attract many people. Of the 34 operas he staged in 1910, only four made money: Richard Strauss's new operas Elektra and Salome (which were very popular), and The Tales of Hoffmann and Die Fledermaus.

In 1911 and 1912, the Beecham Symphony Orchestra played for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (Russian Ballet). Beecham was praised for conducting Stravinsky's difficult new music for Petrushka with very little notice or rehearsal. While in Berlin, Beecham and his orchestra were a big success. The Berlin newspapers said the orchestra was one of the best in the world.

Beecham's 1913 seasons included the first British performance of Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier. He also put on a "Grand Season of Russian Opera and Ballet" at Drury Lane. This season included three operas, all new to Britain and starring the famous singer Feodor Chaliapin. There were also 15 ballets, with leading dancers like Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina. This included the first British performance of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, just six weeks after its first performance in Paris. Beecham didn't conduct during this season.

During the First World War, Beecham worked hard, often without pay, to keep music alive in London and other British cities. He conducted for and financially supported the Hallé Orchestra, the LSO, and the Royal Philharmonic Society. In 1915, he formed the Beecham Opera Company, mostly with British singers, performing across the country. In 1916, he was made a knight and became a baronet after his father's death.

After the war, Beecham temporarily stopped conducting to deal with a big financial problem.

Covent Garden Estate and Financial Matters

Before the war, Beecham's father, Sir Joseph Beecham, had agreed to buy the Covent Garden estate in London. This was a huge deal, but the war started, and new rules made it impossible to finish the purchase. When Sir Joseph died in 1916, the deal was still not complete.

Thomas Beecham and his brother Henry had to sell parts of their father's estate to pay off the debt for Covent Garden. For more than three years, Beecham was away from music, working to sell property worth over £1 million. By 1923, enough money was raised, and the debts were paid. In 1924, the Covent Garden property and the family's pill-making business were combined into one company, Beecham Estates and Pills. Beecham owned a large part of this company.

London Philharmonic Orchestra

After his break, Beecham returned to conducting in March 1923 with the Hallé Orchestra. He came back to London the next month, conducting a combined orchestra. He didn't have his own orchestra anymore, so he worked with the London Symphony Orchestra for the rest of the 1920s.

In 1931, a young conductor named Malcolm Sargent suggested to Beecham that they start a new orchestra with regular salaries, funded by Sargent's wealthy supporters. They tried to reorganize the London Symphony Orchestra, but the LSO, which was run by its musicians, didn't want to remove or replace players. In 1932, Beecham decided to start a completely new orchestra with Sargent.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) was formed with 106 musicians. It included some young musicians fresh from music school, many experienced players from other orchestras, and 17 top members from the LSO.

The orchestra played its first concert on October 7, 1932, conducted by Beecham. The audience loved it, clapping and cheering loudly. Over the next eight years, the LPO played many concerts, performed for Beecham's opera seasons at Covent Garden, and made over 300 recordings. His secretary, Berta Geissmar, wrote that Beecham and the orchestra had a great relationship. He treated rehearsals as a team effort, and the musicians gave their best performances for him.

By the early 1930s, Beecham had a lot of control over the Covent Garden opera seasons. He became the artistic director, focusing on the music, while Geoffrey Toye managed the business side. From 1935 to 1939, Beecham was in sole control, bringing in famous guest singers and conductors. He conducted about a third to half of the performances each season. He planned to perform the complete Les Troyens by Berlioz in 1940, but World War II started, and the season was canceled. Beecham didn't conduct at Covent Garden again until 1951.

Beecham took the London Philharmonic on a tour of Germany in 1936. Some people complained that he was being used by Nazi leaders. Beecham agreed to a Nazi request not to play a symphony by Felix Mendelssohn, who was Jewish. In Berlin, Adolf Hitler attended Beecham's concert. After this tour, Beecham refused more invitations to perform in Germany, though he did conduct at the Berlin State Opera in 1937 and 1938.

As his sixtieth birthday approached, doctors told Beecham to take a year off from music. He planned to go to a warm country. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation had been trying to get him to conduct in Australia for years. When war broke out on September 3, 1939, he had to delay his plans. He worked to secure the future of the London Philharmonic, which had lost its funding due to the war. Before leaving, Beecham raised a lot of money for the orchestra and helped its members form their own self-governing group.

1940s: America and Royal Philharmonic

Beecham left Britain in the spring of 1940, going first to Australia and then to North America. He became the music director of the Seattle Symphony in 1941. In 1942, he joined the Metropolitan Opera in New York as a senior conductor. He conducted many French operas like Carmen and Manon. He also guest conducted with 18 other American orchestras.

In 1944, Beecham returned to Britain. He had a great reunion with the London Philharmonic. However, the orchestra, which was now run by its musicians, wanted to hire him as a salaried artistic director. Beecham refused, saying he wouldn't be controlled by any orchestra. He decided to start another great orchestra. When Walter Legge founded the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1945, Beecham conducted its first concert. But he didn't want a salaried job from Legge either.

In 1946, Beecham founded the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO). He made an agreement that the new orchestra would play at all the Royal Philharmonic Society's concerts. Beecham also arranged for the RPO to be the main orchestra at the Glyndebourne Festival each summer. He got financial support from record companies in the US and Britain. Like before, Beecham's assistants hired musicians from various places. The RPO became known for its excellent woodwind players, often called "The Royal Family."

Beecham's long connection with the Hallé Orchestra ended after John Barbirolli became its chief conductor in 1944. Beecham was upset when he was removed from his honorary position with the Hallé. However, his relationship with the Liverpool Philharmonic, which he had first conducted in 1911, continued well after the war.

Later Years and Death

Beecham, called "Britain's first international conductor" by the BBC, took the RPO on a demanding tour through the United States, Canada, and South Africa in 1950. During the North American tour, he conducted 49 concerts almost every day. In 1951, he was invited to conduct at Covent Garden again after 12 years. The opera company was now funded by the government and run differently. Beecham, though he had been angry about being excluded, wasn't suited for this new way of working.

Between 1951 and 1960, Beecham conducted 92 concerts at the Royal Festival Hall. His concerts often included symphonies by Bizet, Franck, Haydn, Schubert, and Tchaikovsky. He also performed Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben and concertos by Mozart and Saint-Saëns. He often featured music by Delius and Sibelius, and many of his favorite shorter pieces.

In the summer of 1958, Beecham conducted an opera season in Buenos Aires, Argentina. These were his last opera performances. His wife, Betty Humby, died suddenly during this season. Beecham's own final illness prevented him from conducting The Magic Flute at Glyndebourne and a last performance at Covent Garden.

Sixty-six years after his first visit to America, Beecham made his last tour there in late 1959, conducting in several cities. He also conducted in Canada. He flew back to London on April 12, 1960, and did not leave England again. His final concert was on May 7, 1960. The program included the Magic Flute Overture, Haydn's Military Symphony, his own arrangement of Handel's music, Schubert's Symphony No. 5, a piece by Delius, and the Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah.

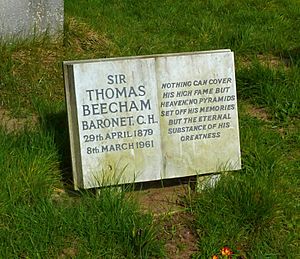

Sir Thomas Beecham passed away from a heart attack at his London home on March 8, 1961, at the age of 81. He was buried two days later. Later, his remains were moved to St Peter's Churchyard at Limpsfield, Surrey, near the grave of Delius and his wife.

Personal Life

Beecham was married three times. In 1903, he married Utica Celestina Welles. They had two sons: Adrian, born in 1904, who became a composer, and Thomas, born in 1909. After his second child was born, Beecham's first marriage began to break down. By 1911, he was no longer living with his family. His first wife, Utica, never remarried after Beecham divorced her in 1943.

Around 1909 or 1910, Beecham became very close with Maud Alice, also known as Lady Cunard. This relationship continued for many years, even though he had other connections. Lady Cunard worked tirelessly to raise money for his musical projects.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Beecham also had a relationship with Dora Labbette, a singer, with whom he had a son, Paul Strang, born in 1933.

In 1943, Beecham divorced Utica to marry Betty Humby, a concert pianist 29 years younger than him. They were a devoted couple until her death in 1958. On August 10, 1959, two years before he died, he married his former secretary, Shirley Hudson, in Zurich. She was 27, and he was 80.

Musical Preferences

Handel, Haydn, and Mozart

The earliest composer whose music Beecham often performed was Handel. Beecham called him "the great international master of all time." When performing Handel, Beecham didn't follow strict historical rules. He changed Handel's music to fit modern tastes, just like Mendelssohn and Mozart had done. At a time when Handel's operas were barely known, Beecham knew them so well that he created ballets and other pieces from them. He also brought Handel's oratorio Solomon back to the stage after many years.

With Haydn, Beecham also didn't try to play the music exactly as it was written. He used older versions of the scores and played the music in a romantic style. He recorded all twelve of Haydn's "London" symphonies and often included them in his concerts. He also conducted some of Haydn's earlier works and regularly performed The Seasons. In 1944, he added The Creation to his performances.

For Beecham, Mozart was "the central point of European music." He treated Mozart's music with more respect than most other composers. He completed Mozart's unfinished Requiem and introduced London audiences to operas like Così fan tutte and Die Entführung aus dem Serail. He also regularly performed The Magic Flute, Don Giovanni, and The Marriage of Figaro. He thought Mozart's best piano concertos were "the most beautiful compositions of their kind in the world" and played them many times with Betty Humby-Beecham and other pianists.

German Music

Beecham had mixed feelings about 19th-century German music. He often spoke badly about composers like Beethoven and Wagner, but he still conducted their works very successfully. He once said, "Wagner, though a tremendous genius, gorged music like a German who overeats." Despite his criticisms, Beecham conducted all of Beethoven's symphonies during his career and recorded many of them.

Beecham was not especially known for his Bach performances, but he chose a Bach piece (arranged by himself) for his debut at the Metropolitan Opera. He was selective with Brahms's music. He was especially good at the Second Symphony but rarely conducted the others.

Beecham loved Wagner's music, even though he often complained about how long and repetitive it was. He conducted almost all of Wagner's main operas. Critics noted that Beecham's Wagner performances were very lyrical and musical.

Richard Strauss had a lifelong supporter in Beecham, who introduced Elektra, Salome, Der Rosenkavalier, and other operas to England. Beecham performed Ein Heldenleben from 1910 until his last year. Strauss even gave Beecham a framed manuscript of Elektra as a gift, calling him "my highly honoured friend... and distinguished conductor of my work."

French and Italian Music

The Académie du Disque Français (a French music award group) said that "Sir Thomas Beecham has done more for French music abroad than any French conductor." Berlioz was a very important composer in Beecham's repertoire throughout his career. At a time when Berlioz's works were rarely performed, Beecham presented most of them and recorded many. Beecham is considered one of the two most important modern performers of Berlioz's music.

Beecham's choices of French music were very varied. He didn't often conduct Ravel but regularly performed Debussy. Other French composers he liked included Bizet, Delibes, Grétry, Lalo, and Saint-Saëns. Many of Beecham's later recordings of French music were made in Paris with the Orchestre National de France.

Of the many operas by Verdi, Beecham conducted eight during his career, including Il trovatore, La traviata, Aida, and Otello. Beecham met Puccini in 1904. Beecham rarely conducted Madama Butterfly, but he did conduct Tosca, Turandot, and La bohème. His 1956 recording of La bohème is still highly recommended by critics today.

Delius, Sibelius, and "Lollipops"

Except for Delius, Beecham generally didn't like the music of his own country and its main composers. However, Beecham's strong support for Delius helped the composer become much more famous. Eric Fenby, Delius's assistant, said Beecham was the best at conducting Delius's music. Beecham held Delius Festivals in 1929 and 1946 and performed his works throughout his career. He conducted the first British performances of Delius's operas A Village Romeo and Juliet and Koanga, and the world premiere of Irmelin.

Another important 20th-century composer Beecham liked was Sibelius. Sibelius himself recognized Beecham as a great conductor of his music. In a live recording of Sibelius's Second Symphony, Beecham can be heard shouting encouraging words to the orchestra at exciting moments.

Beecham sometimes dismissed famous classical pieces. He once said, "I would give the whole of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos for Massenet's Manon, and would think I had vastly profited by the exchange." He was also famous for playing short, light pieces as encores, which he called "lollipops." Some of the most well-known were Berlioz's Danse des sylphes and Gounod's Le Sommeil de Juliette.

Recordings

The composer Richard Arnell said that Beecham preferred making records to giving concerts. He felt that audiences sometimes got in the way of the music. However, the critic Trevor Harvey wrote that studio recordings could never fully capture the excitement of Beecham performing live.

Beecham started making recordings in 1910. His first recordings were excerpts from Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann and Johann Strauss's Die Fledermaus. In 1915, he began recording for Columbia. When new electrical recording technology came out in 1925–26, it allowed for recording a full orchestra with much better sound quality, and Beecham quickly used this new method. He often recorded his favorite works multiple times to take advantage of better technology over the years.

From 1926 to 1932, Beecham made over 70 recordings, including an English version of Gounod's Faust and the first of three recordings of Handel's Messiah. He began recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1933, making over 150 recordings for Columbia. One of his most famous pre-war recordings was the first complete recording of Mozart's The Magic Flute with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1937–38, which is still considered legendary. In 1936, during his German tour, Beecham conducted the world's first orchestral recording on magnetic tape.

During his time in the US and afterward, Beecham recorded for American Columbia Records and RCA Victor. His RCA recordings include important works like Beethoven's Fourth Symphony and Sibelius's Sixth Symphony. Some of his RCA recordings were only released in the US. His famous 1956 complete recording of Puccini's La bohème is still highly recommended by reviewers.

For the Columbia label, Beecham recorded his last or only versions of many works by Delius. Other Columbia recordings from the early 1950s include Beethoven's Eroica and Pastoral symphonies.

From his return to England after World War II until his final recordings in 1959, Beecham continued working with HMV and British Columbia, which had merged to form EMI. From 1955, his EMI recordings in London were made in stereo. He also recorded in Paris. For EMI, Beecham recorded two complete operas in stereo: Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Carmen. His last recordings were made in Paris in December 1959. Beecham's EMI recordings have been reissued many times on LPs and CDs. In 2011, to mark 50 years since his death, EMI released 34 CDs of his recordings.

Relationships and Sayings

Beecham's relationships with other British conductors were not always friendly. Sir Henry Wood was jealous of his success, and Sir Adrian Boult found him difficult. Sir John Barbirolli didn't trust him. Sir Malcolm Sargent worked with him to found the London Philharmonic and was a friend, but Beecham sometimes made witty, unkind jokes about him. Beecham often got along well with foreign conductors. He liked and supported Wilhelm Furtwängler, admired Pierre Monteux, and helped Rudolf Kempe become his successor with the RPO.

Beecham is famous for his many clever sayings. A book called Beecham Stories was published in 1978, full of his witty remarks and stories about him. Some of his well-known quotes include: "A musicologist is a man who can read music but can't hear it"; and his rule for a good performance: "There are only two things requisite so far as the public is concerned for a good performance: that is for the orchestra to begin together and end together; in between it doesn't matter much." At his 70th birthday celebration, after telegrams were read from famous composers, he asked, "Nothing from Mozart?"

He didn't care much for everyday tasks like answering letters. Once, during financial difficulties, two thousand unopened letters were found among his papers.

Honors and Commemorations

Beecham was knighted in 1916 and became a baronet later that year when his father died. In 1938, the President of France gave him the Legion of Honour. In 1955, he received the Order of the White Rose of Finland. He was also made a Companion of Honour in 1957. He received honorary music degrees from several universities, including Oxford and London.

A play called Beecham, by Caryl Brahms and Ned Sherrin, celebrates the conductor and uses many of his famous stories. It first opened in 1979.

In 1980, the Royal Mail put Beecham's image on a postage stamp in a series honoring British conductors. The Sir Thomas Beecham Society works to keep Beecham's legacy alive through its website and by releasing historical recordings.

In 2012, Beecham was voted into the first "Hall of Fame" by Gramophone magazine.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Beecham para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Beecham para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |