Arnold Bax facts for kids

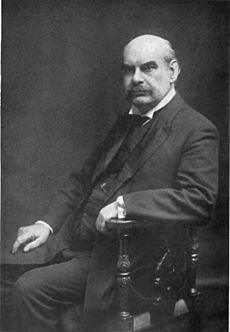

Sir Arnold Edward Trevor Bax (born November 8, 1883 – died October 3, 1953) was an English composer, poet, and writer. He wrote many different kinds of music, including songs, music for choirs, and pieces for solo piano. However, he is most famous for his orchestral music. He wrote seven symphonies and many symphonic poems, which are like musical stories. For a while, many people thought he was the most important British composer of symphonies.

Bax grew up in Streatham, a part of London, in a wealthy family. His parents encouraged him to study music. Because his family had money, he could compose the music he wanted, without worrying about what was popular. This made him an important but somewhat separate figure in music. When he was a student at the Royal Academy of Music, Bax became very interested in Ireland and Celtic culture. This had a big effect on his early music. Before World War I, he lived in Ireland and joined writing groups in Dublin. He wrote stories and poems using the pen name Dermot O'Byrne. Later, he also became interested in Nordic culture, which influenced his music after World War I.

Between 1910 and 1920, Bax wrote a lot of music. This included the symphonic poem Tintagel, which is his most famous work. During this time, he formed a close and lasting musical partnership with the pianist Harriet Cohen. In the 1920s, he started writing his seven symphonies, which are a very important part of his orchestral music. In 1942, Bax was given the special title of Master of the King's Music, but he didn't compose much in this role. Towards the end of his life, his music was seen as old-fashioned, and after he died, it was mostly forgotten. But from the 1960s onwards, people started to rediscover his music, mainly through new recordings. Even so, his music is not often played in concert halls today.

Contents

Life and Music Journey

Growing Up and Early Studies

Arnold Bax was born in Streatham, London, into a well-off family. He was the oldest son of Alfred Ridley Bax and Charlotte Ellen. His younger brother, Clifford Lea Bax, became a writer. Arnold's father was a lawyer, but he didn't need to work because the family had money. In 1896, his family moved to a large house in Hampstead. Bax later said that even though he wished he had grown up in the countryside, their big gardens were the next best thing. He was a musical child and could play the piano from a very young age.

After attending a preparatory school in Balham, Bax went to the Hampstead Conservatoire in the 1890s. This school was run by Cecil Sharp, who loved English folk songs and dances. However, Bax was not interested in folk music, unlike many other British composers of his time like Vaughan Williams and Holst.

In 1900, Bax went to the Royal Academy of Music and stayed there until 1905. He studied composing with Frederick Corder and piano with Tobias Matthay. Corder was a big fan of Wagner's music, which was a major influence on Bax when he was young. Bax later said he spent many years deeply involved in Wagner's music. Bax also discovered and studied the music of Debussy on his own. The teachers at the academy often didn't approve of Debussy's music or that of Richard Strauss.

Bax won important awards for his compositions and was known for being able to read difficult music very well. However, he didn't get as much recognition as other students like Benjamin Dale and York Bowen. He was a very skilled pianist, but he didn't want to be a solo performer. Unlike most other composers, he had his own money, so he didn't need to earn a living from music. This meant he was free to compose whatever he wanted. Some people thought this freedom might have hurt his music because he didn't always learn the discipline to express his ideas clearly.

After leaving the Academy, Bax visited Dresden, where he saw the first performance of Strauss's opera Salome. He also heard Mahler's music for the first time, which he found interesting but sometimes confusing. The Irish poet W. B. Yeats was another important influence on young Bax. Bax's brother Clifford introduced him to Yeats's poems and to Ireland. Inspired by Yeats's poem The Wanderings of Oisin, Bax visited the west coast of Ireland in 1902. He felt an immediate connection to Celtic culture. His first piece of music performed in public was an Irish song called "The Grand Match" in 1902.

Early Composing Career

Bax started to move away from the influences of Wagner and Strauss. He began to use what he thought of as an Irish musical style. In 1908, he started a series of tone poems called Eire. These pieces are seen as the beginning of his truly mature style. The first of these, Into the Twilight, was first performed in 1909. The next year, Henry Wood asked him to write the second, In the Faëry Hills. This piece received mixed reviews. Some critics liked how it created a mysterious atmosphere, while others found it unclear.

Bax's personal wealth allowed him to travel to the Russian Empire in 1910. He was following Natalia Skarginska, a young Ukrainian woman he had met in London. The romantic part of the trip didn't work out, but it helped his music. In Saint Petersburg, he discovered and loved ballet. He was inspired by Russian music, which led to pieces like his First Piano Sonata and "May Night in the Ukraine." Bax was like a "musical magpie," taking new ideas and making them his own. Russian music continued to influence him until World War I.

After returning to England, Bax married the pianist Elsita Luisa Sobrino in 1911. They lived in London for a short time before moving to Rathgar, a suburb of Dublin, Ireland. They had two children, Dermot and Maeve. In Dublin, Bax became known in writing groups under the name "Dermot O'Byrne." He published stories, poems, and a play. Some of his writings were seen as supporting the Irish republican cause, and the government even banned some of them.

World War I and New Influences

When World War I began, Bax returned to England. He had a heart condition that meant he couldn't join the military. While other composers like Vaughan Williams were fighting, Bax was able to write a lot of music. He reached his full artistic potential in his early thirties. Some of his well-known works from this time include the orchestral tone poems November Woods (1916) and Tintagel (1917–19).

During his time in Dublin, Bax had many friends who supported Irish independence. The Easter Rising in April 1916, and the executions of its leaders, deeply upset him. He put his feelings into some of his music, like the orchestral piece In Memoriam and the "Elegiac Trio" for flute, viola, and harp (1916). He also wrote poems about it.

Besides Irish influences, Bax also found inspiration in Nordic traditions. He was inspired by the Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Icelandic sagas. His Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra (1917) is seen as a turning point from his Celtic to his Nordic style.

During the war, Bax started a close relationship with the pianist Harriet Cohen. She became his musical inspiration for the rest of his life. He wrote many pieces for her, and she was the person he dedicated 18 of his works to. He moved to a flat in Swiss Cottage, London, where he lived until World War II. He often started his music there and then took it to quiet places like Glencolmcille in Ireland or Morar in Scotland to finish it.

Between the World Wars

After World War I, critics noticed that the Celtic influence in Bax's music was fading. A more serious and abstract style was appearing. From the 1920s onwards, Bax rarely used old legends for inspiration. He became known as an important, though somewhat separate, figure in British music. Many of his major works from the war years were performed in public, and he began writing symphonies. For a time, many people considered Bax the leading British symphonist.

Bax's First Symphony was written in 1921–22. When it was first performed, it was a big success, even though it had a strong and sometimes harsh sound. Critics described it as dark and serious. One newspaper said it was "full of strong, almost loud, energy." Another called it "a truly great English symphony." This symphony was very popular at the Proms concerts for several years. However, Bax's peak of popularity was relatively short, and other composers like Vaughan Williams and William Walton soon became more famous. His Third Symphony, finished in 1929, became one of his most popular works, thanks to conductor Henry Wood.

In the mid-1920s, Bax met Mary Gleaves. His close musical partnership with Harriet Cohen continued, but Gleaves became his life companion until he died.

In the 1930s, Bax composed the last four of his seven symphonies. Other works from this time include the popular Overture to a Picaresque Comedy (1930) and several pieces for small groups of instruments. His Cello Concerto (1932) was written for Gaspar Cassadó, but Cassadó stopped playing it. Bax was very disappointed that this work was not performed more often.

Bax was knighted in 1937, which meant he became "Sir Arnold Bax." He didn't expect or seek this honor and was surprised to receive it. As the 1930s went on, he composed less. He joked that he wanted to "retire, like a grocer." One of his compositions from this time was the Violin Concerto (1938). He wrote it hoping the famous violinist Jascha Heifetz would play it, but Heifetz never did. It was first performed in 1942 by Eda Kersey.

Later Years (1940s and 1950s)

After the death of Sir Walford Davies in 1941, Bax was chosen to take his place. This choice surprised many people because Bax was not a typical "establishment" figure. He himself didn't like the idea of official duties. The Times newspaper thought it wasn't a good appointment because Bax didn't enjoy official tasks. Still, Bax wrote a few pieces for royal events, including a march for the Coronation in 1953.

When World War II started, Bax moved to the White Horse Hotel in Storrington, Sussex, where he lived for the rest of his life. He stopped composing for a while and wrote a book of memories about his early life called Farewell, My Youth. Later in the war, Bax was asked to write music for a short film called Malta G. C.. He also wrote music for David Lean's film Oliver Twist (1948) and another short film, Journey into History (1952). Other works from this time include Morning Song for piano and orchestra, and the Left-Hand Concertante (1949), both written for Harriet Cohen.

In his final years, Bax enjoyed a quiet retirement. He loved watching cricket matches more than attending performances of his own music. In 1950, after hearing his Third Symphony, he thought about writing an eighth. However, his health declined, which made it harder for him to focus on large compositions. In 1952, he wrote, "I doubt whether I shall write anything else... I have said all I have to say." Celebrations were planned for his seventieth birthday in November 1953. But while visiting Cork in October 1953, Bax died suddenly from heart failure. He was buried in St. Finbarr's Cemetery, Cork.

Bax's Music Style

Another composer, Arthur Benjamin, said that Bax was like a "fountain of music" because he had so many ideas. Bax's music often combines strength with a touch of sadness. His early music can be difficult to play and complex in its sound. But from about 1913 onwards, his style became simpler. Some experts believe Bax's best works were written between 1910 and 1925, including The Garden of Fand, Tintagel, and his first two symphonies. By the 1930s, Bax's music was no longer seen as new or difficult, and it started to get less attention.

The conductor Vernon Handley, who knows Bax's music well, said that Bax was influenced by composers like Rachmaninoff and Sibelius, as well as Richard Strauss and Wagner. Bax also knew about jazz and many other European composers, and these influences found their way into his music.

York Bowen thought it was a shame that Bax's orchestral works often needed very large groups of musicians. This made them harder to perform. However, the composer Eric Coates said that orchestral musicians loved playing Bax's music. He wrote for each instrument as if he played it himself.

His Symphonies

In 1907, Bax started working on a huge symphony that would have lasted about an hour. He later said, "Happily, it never has!" But he left a complete piano sketch, which was arranged for orchestra in 2012–13 and recorded. This early work shows a strong Russian influence.

Bax wrote his seven completed symphonies between 1921 and 1939. Some people used to think they were shapeless, but in fact, they are very strong and often sharp. They also have a clear structure. The symphonies can be divided into two groups: the first three and the last three, with the Fourth Symphony acting as a more cheerful break in between. The first three symphonies show a strong Celtic influence, reflecting Bax's feelings about the Easter Rising. The Fourth Symphony is generally seen as more optimistic. The Fifth and Sixth symphonies are more serious. The Sixth Symphony is known for its "magnificent final movement." The Seventh Symphony has a sadder, simpler tone, very different from his earlier, more complex music.

Music for Solo Instruments and Orchestra

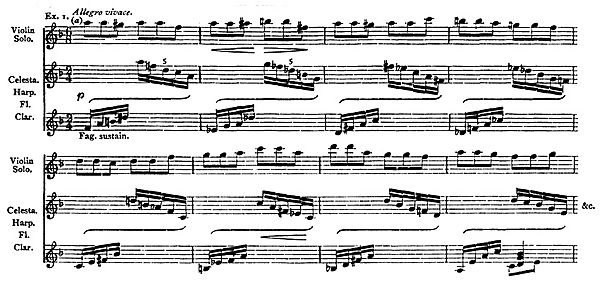

Bax's first major work for a solo instrument and orchestra was the 50-minute Symphonic Variations (1919), written for Harriet Cohen.

The Cello Concerto (1932) was Bax's first attempt at a traditional concerto. It uses a smaller orchestra than he usually did. Even though it has many subtle musical details, it has never been one of his most famous works. The Violin Concerto (1937–38) is, like his last symphony, more relaxed than much of his earlier music. One critic called it "unusually fine." Bax himself described it as being in the romantic style of Joachim Raff.

Among his shorter works for solo instrument and orchestra is Variations on the Name Gabriel Fauré (1949) for harp and strings. Bax's last piece for solo instrument and orchestra was a short work for piano and orchestra (1947). He wrote it as Master of the King's Music to celebrate Princess Elizabeth's twenty-first birthday.

Other Orchestral Works

Bax's tone poems vary in style and popularity. His impressionistic tone poem In the Faëry Hills is described as a "short and attractive piece." It was somewhat successful. However, Spring Fire (1913) was a difficult work and was not performed during Bax's lifetime. During World War I, Bax wrote three tone poems. Two of them – The Garden of Fand (1913–16) and November Woods (1917) – are still sometimes played today. The third, Tintagel (1917–19), was the only work by which Bax was known to the public for a decade after his death. All three pieces are musical pictures of nature. The orchestral piece that was forgotten the longest was In memoriam (1917), a sad piece for Patrick Pearse, who was executed after the Easter Rising. This work was not played until 1998. Bax later used the main tune from it in his music for the film Oliver Twist (1948). Another of Bax's impressionistic tone poems is "Nympholept," based on a poem about a wanderer enchanted by a wood nymph. This piece was also not performed during Bax's life.

Oliver Twist was Bax's second film score. The first was for a short wartime film called Malta, G. C.. A suite of music from Malta, G. C. includes a "notable March" that sounds like the grand music of Elgar. Bax's third and last film score was for a short film called Journey into History in 1952.

Other orchestral works include Overture, Elegy and Rondo (1927), which is a lighter piece. The Overture to a Picaresque Comedy (1930) was one of his most popular works for a time. Bax described it as a "Straussian pastiche," meaning it was a playful imitation of Richard Strauss's style.

Songs and Choral Music

A critic once asked Bax why he never set any of Yeats's poems to music. Bax replied, "What, I? I should never dare!" He felt that even the best musical setting might not do justice to a poem. This feeling eventually made him stop writing songs completely.

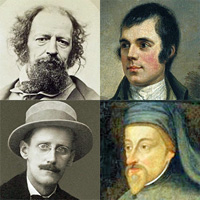

When he first started composing, songs and piano music were very important to Bax's work. Some of his early songs have very difficult piano parts that can sometimes overpower the singer. "The White Peace" (1907) is one of his most popular songs, known for its simpler piano part. Bax set poems by many different writers, including his brother Clifford, Burns, Chaucer, Hardy, Joyce, and Tennyson. He particularly mentioned his "A Celtic Song-Cycle" (1904). Some of his later songs, like "In the Morning" (1926), are considered masterpieces of 20th-century song.

Bax wrote many pieces for choirs, both secular (non-religious) and religious. Although he was a member of the Church of England, his choral music is not usually described as devotional. It is often rich and expressive. His largest work for unaccompanied voices is Mater ora Filium (1921), inspired by William Byrd's music. Other choral works include settings of words by Shelley and Masefield.

Chamber and Solo Piano Music

Among Bax's early chamber works (music for small groups of instruments), some of the most successful include the Phantasy for viola and the Trio for piano, violin, and viola. His Second Violin Sonata (1915) is seen as one of his most unique works from that time. The Piano Quintet is also considered a very rich and inventive piece. Other important chamber works include the First String Quartet (1918), the "grittier" Second Quartet (1925), the Viola Sonata (1922), and the Sonata for Flute and Harp (1928).

Bax was one of the few British composers to write a lot of music for solo piano. He published four piano sonatas (1910–32), which are as important to his piano music as his symphonies are to his orchestral music. The first two sonatas are in one long movement, while the third and fourth have the usual three movements. Bax's own skill as a pianist is clear in how demanding many of his piano pieces are. Composers like Chopin, Liszt, and Russian composers influenced his piano style. For two pianos, Bax wrote two tone poems, Moy Mell (1917) and Red Autumn (1931). His shorter piano pieces include charming miniatures like In a Vodka Shop (1915) and A Hill Tune (1920).

His Music: Forgotten and Rediscovered

In his later years, Bax's music became less popular. The conductor Sir John Barbirolli wrote that Bax felt his music was no longer "fashionable." After Bax died, his music was largely forgotten.

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were big changes in the music world. Many people thought that British music had been too old-fashioned. Composers like Bax were seen as out of date. It took about twenty years for the music of British romantic composers, including Bax, to start gaining attention again.

The revival of Bax's music began with performances by Vernon Handley and recordings by Lyrita Recorded Edition in the 1960s. Books about Bax's life and music were also published. In 1983, for his 100th birthday, BBC Radio 3 broadcast many programs featuring his music. In 1985, the Sir Arnold Bax Trust was created to promote his work, including live performances, recordings, and publications. Since then, many of Bax's works have been recorded. However, even with many recordings, his music is still not often played in concert halls.

Recordings of Bax's Music

Bax himself made two recordings as a pianist in 1929. He recorded his own Viola Sonata with Lionel Tertis and Delius's Violin Sonata No 1 with May Harrison. Of his symphonies, only the Third was recorded during his lifetime, in 1944. Other pieces like the Viola Sonata and Mater ora Filium were also recorded in the late 1930s. The first recording of the tone poem Tintagel was made in 1928. By 1955, it was hard to find Bax's music on record.

Today, there are many more recordings of Bax's music. There are three complete sets of his symphonies available on CD. His major tone poems and other orchestral works have also been recorded many times. Bax's chamber music is well represented on recordings, with many versions of pieces like the Elegiac Trio and the Clarinet Sonata. Much of his piano music has been recorded by various pianists. Many of his choral works, especially Mater ora Filium, and a selection of his songs are also available on disc.

Awards and Recognition

Bax received several important awards during his life. He was given gold medals from the Royal Philharmonic Society (1931) and the Worshipful Company of Musicians (1931). He also received honorary doctorates from the universities of Oxford (1934), Durham (1935), and the National University of Ireland (1947). In 1955, a Bax Memorial Room was opened at University College, Cork.

Bax was knighted in 1937, becoming "Sir Arnold Bax." In 1953, he was given an even higher honor, the KCVO. In 1993, a blue plaque was placed on his birthplace in Streatham to remember him.

In 1992, filmmaker Ken Russell made a television film called The Secret Life of Arnold Bax, which showed Bax's later years. Russell played Bax, and Glenda Jackson played Harriet Cohen.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Arnold Bax para niños

In Spanish: Arnold Bax para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |