Charles-Valentin Alkan facts for kids

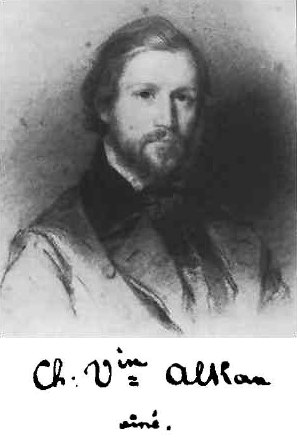

Charles-Valentin Alkan (born November 30, 1813 – died March 29, 1888) was a French-Jewish composer and an amazing piano player. In the 1830s and 1840s, he was one of the top pianists in Paris, just like his friends Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. He lived almost his whole life in Paris.

Alkan won many awards at the Conservatoire de Paris, a famous music school he joined before he was six years old. He often performed in fancy homes (called salons) and concert halls in Paris. Sometimes, he would stop performing for long periods for personal reasons. Even though he knew many artists in Paris, like Eugène Delacroix and George Sand, he started living a more private life from 1848 onwards. During this time, he kept composing music, mostly for the piano.

He published important collections of long studies (musical exercises) for piano. These included his Symphony for Solo Piano and Concerto for Solo Piano. These pieces are considered some of his best works. They are very complex and difficult to play. In the 1870s, Alkan started performing again. Many young French musicians came to his concerts.

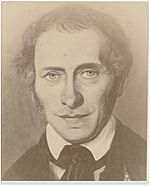

Alkan was proud of his Jewish background. This showed in his life and his music. He was the first composer to use Jewish melodies in classical music. He could speak Hebrew and Greek very well. He spent a lot of time translating the Bible into French. Sadly, this translation, like many of his musical pieces, is now lost. Alkan never married, but his son Élie-Miriam Delaborde was also a brilliant pianist, just like Alkan. He also played the pedal piano and helped publish some of his father's music.

After Alkan died, his music was mostly forgotten for a while. Only a few musicians, like Ferruccio Busoni and Kaikhosru Sorabji, kept it alive. But since the late 1960s, pianists like Raymond Lewenthal and Ronald Smith have recorded his music. This has helped bring his amazing compositions back into the spotlight.

Contents

Life

His Family

Charles-Valentin Alkan was born Charles-Valentin Morhange on November 30, 1813, in Paris. His parents were Alkan Morhange (1780–1855) and Julie Morhange. His father's family came from a Jewish community near Metz, France. Charles-Valentin was the second of six children. He had an older sister and four younger brothers.

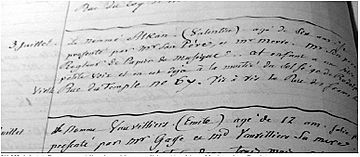

Alkan Morhange supported his family as a musician. Later, he owned a private music school in Paris. Charles-Valentin and his brothers and sister started using their father's first name, Alkan, as their last name. This is how they were known at the Conservatoire and in their careers. His brother Napoléon (1826–1906) became a music professor. His brother Maxim (1818–1897) wrote light music for theaters. His sister, Céleste (1812–1897), was a singer. His brother Ernest (1816–1876) played the flute, and his youngest brother Gustave (1827–1882) published piano dances.

A Child Genius (1819–1831)

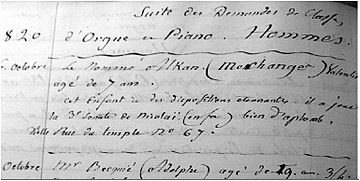

Alkan was a true child prodigy, meaning he was incredibly talented at a very young age. He joined the Conservatoire de Paris when he was unusually young. He studied both piano and organ there. Records show that when he was just over five years old, examiners noted his "pretty little voice" during a music audition. When he was almost seven, examiners said, "This child has amazing abilities" at his piano audition.

Alkan became a favorite student of his teacher, Pierre-Joseph-Guillaume Zimmerman. Zimmerman also taught other famous composers like Georges Bizet and César Franck. At seven, Alkan won a top prize for music. Later, he won prizes for piano (1824), harmony (1827), and organ (1834). When he was seven and a half, he performed publicly for the first time as a violinist. His first published work for piano came out in 1828, when he was 14. Around this time, he also started teaching at his father's school.

Early Success (1831–1837)

In his early years, Alkan continued to teach and perform in Paris. He became friends with many important artists, including Franz Liszt, George Sand, and Victor Hugo. He also became friends with Frédéric Chopin, who arrived in Paris in 1831. In 1832, Alkan played the solo part in his first Concerto da camera for piano and strings. That same year, at 19, he joined an important music society.

Alkan tried twice to win the Prix de Rome, a famous prize for composers, but he didn't succeed. In 1834, he became friends with the Spanish musician Santiago Masarnau. They wrote many letters to each other, which helps us understand Alkan's life. Later in 1834, Alkan visited England and gave concerts there. In 1835, he finished his first truly original piano works, the Twelve Caprices. In 1836, Liszt suggested Alkan for a teaching job in Geneva, but Alkan said no. In 1837, Liszt wrote a very positive review of Alkan's music.

Living in Square d'Orléans (1837–1848)

From 1837, Alkan lived in the Square d'Orléans in Paris. Many famous people lived there, including Marie Taglioni, Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, and Chopin. Chopin and Alkan were close friends and often talked about music. By 1838, at 25, Alkan was at the peak of his career. He gave many concerts, and his new music was being published. He often performed with Liszt and Chopin.

For about six years, Alkan took a break from public performances. During this time, his son, Élie-Miriam Delaborde (1839–1913), was born. Alkan gave his son early piano lessons. His son later became a famous piano player, just like him.

When Alkan returned to performing in 1844, critics were very excited. They praised his amazing technique and called him a "sensation." They also noted that famous people like Liszt, Chopin, Sand, and Dumas came to his concerts. In the same year, he published his piano piece Le chemin de fer (The Railway). Many believe this was the first time a steam engine was shown in music. Between 1844 and 1848, Alkan wrote more difficult pieces, like the 25 Préludes and the sonata Op. 33 'Les quatre âges' (The Four Ages).

Living in Seclusion (1848–1872)

In 1848, Alkan was very upset when he didn't get a top teaching job at the Conservatoire. He had hoped for this position and had a lot of support from friends like Sand and Dumas. This disappointment might explain why he stopped performing in public for a long time. The death of Chopin in 1849 also affected him deeply. Chopin respected Alkan so much that he left him his unfinished piano method, hoping Alkan would complete it. After Chopin died, some of his students started studying with Alkan. Despite his fame, Alkan mostly stayed out of public life for about twenty years.

We don't know much about this period of Alkan's life. We know he composed music and studied the Bible and the Talmud (a collection of Jewish teachings). He wrote many of his most important piano works during this time. These included the Douze études dans tous les tons mineurs (Twelve Studies in all Minor Keys), the Sonatine, and the Esquisses. He also wrote the Sonate de concert for cello and piano. Other musicians, like Hans von Bülow, praised his work, even though Alkan didn't travel much.

From the early 1850s, Alkan also became very interested in the pedal piano, which is a piano with foot pedals like an organ. He gave his first public performances on the pedal piano in 1852, and they were very successful.

Returning to the Stage (1873–1888)

In 1873, Alkan decided to start performing again. He gave a series of six "Small Concerts" at the Érard piano showrooms. This might have been because his son, Delaborde, was becoming a successful concert pianist and was appointed a professor at the Conservatoire. The "Small Concerts" were very popular and became an annual event until at least 1880. Alkan played his own music and pieces by his favorite composers, like Bach. He played both the piano and the pedal piano. His siblings and other musicians, including Camille Saint-Saëns, sometimes joined him.

Young musicians who saw Alkan perform during this time were very impressed. Vincent d'Indy, a young composer, remembered Alkan's "skinny, hooked fingers" playing Bach. He said Alkan's playing was "expressive, crystal-clear." D'Indy also described Alkan playing Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 31, saying it was incredibly moving.

His Death

Charles-Valentin Alkan died in Paris on March 29, 1888, at the age of 74. He was buried on April 1 in the Jewish section of Montmartre Cemetery in Paris. His sister Céleste was later buried in the same tomb.

For many years, a story was told that Alkan died when a bookcase fell on him as he reached for a book. However, a letter from one of his students found later gives a different story. It says Alkan was found after an accident in his kitchen, under a heavy coat rack. He might have fainted and pulled it down on himself. He was taken to his bedroom and died later that evening. The bookcase story might have come from an old legend about a rabbi from Metz, the town where Alkan's family came from.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles-Valentin Alkan para niños

In Spanish: Charles-Valentin Alkan para niños