Westminster Assembly facts for kids

The Westminster Assembly was a special meeting of religious experts and members of the English Parliament. They met from 1643 to 1653 to make big changes to the Church of England. Some Scottish people also joined in. The Assembly created important documents like a new way to run the church, a statement of beliefs called the Westminster Confession of Faith, and two teaching guides called catechisms (the Shorter and Larger). They also made a guide for church services, the Directory for Public Worship. These documents became very important for the Church of Scotland and other Presbyterian churches. They also influenced Congregational and Baptist churches in England and America.

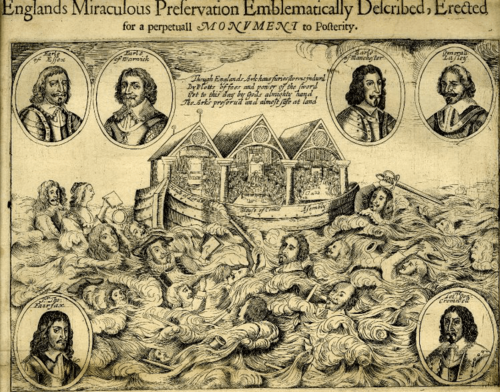

This Assembly was called by the Long Parliament during the First English Civil War. Parliament was influenced by Puritanism, a group that wanted to make the church simpler and more "pure." They disagreed with King Charles I and William Laud, the main archbishop. To get military help from Scotland, Parliament agreed to make the English Church more like the Scottish Church. The Scottish Church was run by elected groups called presbyterianism, not by bishops like the English Church. Scottish advisors came to the Assembly. There were big disagreements about how the church should be run. Most members wanted presbyterianism. But another group, the Congregationalists, wanted each local church to be independent. Parliament tried to set up a presbyterian system, but it didn't fully happen. When the king returned in 1660, all the Assembly's work was cancelled.

The Assembly followed Reformed Protestant ideas, also known as Calvinism. They believed the Bible was God's true word and the basis for all beliefs. They believed in predestination, meaning God chooses some people to be saved. They also used covenant theology, a way of understanding the Bible. Their Confession was the first to teach about the covenant of works. This idea says that before humans sinned, God promised Adam eternal life if he perfectly obeyed God.

Contents

Why the Assembly Was Called

The Parliament called the Westminster Assembly because of growing problems between King Charles I and the Puritans. Puritans believed that church worship should only follow what the Bible said. They felt the Church of England was still too much like the Roman Catholic Church. They wanted to remove all Catholic influences, including the system of rule by bishops.

Under King Charles, people who disagreed with the Puritans were given powerful jobs. The most famous was William Laud, who became the main archbishop in 1633. Puritans were often punished if they spoke out. Laud also brought back old worship practices like kneeling at communion. To Puritans, these changes felt like a step back towards Catholicism.

There were also problems between the king and the Scots. Their church was run by elected assemblies, a system called presbyterianism. King James, Charles's father, tried to force the Scottish Church to use bishops and the English prayer book. Charles continued these efforts, leading to wars with the Scots in 1639 and 1640. Charles needed money for these wars, so he had to call Parliament.

The Long Parliament had many Puritans and people who supported them. They generally disliked the system of bishops. In 1640, a petition signed by 15,000 Londoners asked Parliament to completely get rid of bishops. Parliament began making religious changes. Archbishop Laud was even sent to prison. Courts that had punished Puritans were also closed down.

Starting the Assembly

The idea of a national meeting of religious experts to advise Parliament came up in 1641. This idea was also in a list of complaints Parliament gave to King Charles. But Charles said the church didn't need any changes.

Parliament then passed laws in 1642 to create the Assembly. They said Parliament would choose the members. Charles disagreed, saying only the clergy (church leaders) should choose them.

Despite the king's disapproval, Parliament chose 121 ministers and 30 non-voting members from Parliament itself. Most of these experts were from England. Many were well-known scholars of the Bible and ancient languages. Most were also famous preachers. Even though they disagreed with some church practices, they all considered themselves members of the Church of England.

The Assembly was completely controlled by Parliament. Members could only discuss topics Parliament gave them. They couldn't share their disagreements or information about the meetings with anyone outside Parliament. William Twisse, a respected theologian, was chosen to lead the Assembly.

Early Meetings and Debates

The Assembly's first meeting started with a sermon on July 1, 1643, in Westminster Abbey. The room was so full that members of Parliament had to arrive early to get seats. After the sermon, they moved to the Henry VII Chapel. Later, they moved to the warmer Jerusalem Chamber.

On July 6, Parliament gave them rules. They were told to look at the first ten of the Thirty-Nine Articles, which were the Church of England's main beliefs. The Assembly promised to only teach what they believed was true. They split into three groups to prepare topics for discussion. They also had over 200 smaller groups for other tasks.

The Assembly decided that all beliefs in the Thirty-Nine Articles had to be proven from the Bible. Progress was slow because members gave long speeches. One early disagreement was about the Apostles' Creed, Nicene Creed, and Athanasian Creed. These are basic statements of Christian belief. Some members didn't want to be bound by these old creeds. This showed early on that there were deep differences among the members.

Debating Church Government

During the Civil War, Parliament knew they needed help from the Scots. In return for military help, the Scottish Parliament made the English sign the Solemn League and Covenant in 1643. This agreement said the English Church would become more like the Scottish Church. Scottish advisors came to London and joined the Assembly.

On October 12, 1643, Parliament told the Assembly to stop working on the Thirty-Nine Articles. Instead, they were to create a common way to run the church for both England and Scotland. The Assembly spent a lot of time on this topic.

Most Assembly members supported presbyterian polity, where the church is governed by elected groups of church leaders and regular members. However, many were not completely set on this idea.

There were also several Congregationalists. They believed each local church should be independent. These members were sometimes called the "dissenting brethren." They were important because Oliver Cromwell and his army, who were winning the war, supported congregationalism.

A third group was called Erastians. They believed the government should have a lot of power over the church. Only two religious experts in the Assembly were Erastian. But because Parliament was in charge of the Assembly, and some Members of Parliament were Erastian, their ideas had a big impact.

Debates about church leaders began in October. Many members were worried about new religious groups forming and the lack of a clear way to appoint ministers. The Congregationalists believed a church was just one local group. But the majority saw the national church as one whole. Despite these debates, people hoped they could find a church government that everyone would agree on.

However, in January 1644, the five main Congregationalists published a pamphlet. It argued that their system was better for government control than the presbyterian system. By January 17, most of the Assembly wanted a presbyterian system like Scotland's. But the Congregationalists were allowed to keep arguing their case.

On February 21, it became clear how different the groups were. Philip Nye, a Congregationalist, said that a presbytery (a group of church leaders) overseeing local churches would become too powerful. This caused a strong reaction from the presbyterians. The next day, the Assembly began to plan a presbyterian government. They tried to find ways to include the Congregationalists throughout 1644. But in November, the Congregationalists gave their reasons for disagreeing to Parliament. In December, the majority submitted their plan for a presbyterian government.

Problems with Parliament

Relations between the Assembly and Parliament got worse in 1644. Parliament ignored the Assembly's request to stop certain people from taking communion. Parliament members agreed that the sacrament should be pure. But many disagreed with the Assembly about who had the final power to excommunicate (kick someone out of the church). They believed the government should have this power.

By 1646, Oliver Cromwell's army had won the war for Parliament. Cromwell and many in the army strongly supported religious toleration for all Christians. This made it unlikely that a strict presbyterian church without freedom for others would be set up.

In May 1645, Parliament passed a law allowing people kicked out of the church to appeal to Parliament. Another law in October listed the only sins for which the church could excommunicate people. The Assembly protested this, and Parliament asked them nine questions about it.

The "Nine Queries" focused on whether church government was established by divine right (by God's command). The presbyterian members could defend their view. But they didn't want to answer the questions because it would show how divided the Assembly was.

In July 1647, Cromwell's army took over London. Parliament passed a law for religious tolerance. This meant the Assembly's idea of a national, required presbyterian church would not happen. In London, only 64 out of 108 churches became presbyterian. A planned national presbyterian meeting never happened. Many presbyterians still set up their own churches. But when the king returned in 1660, the system of bishops was brought back.

The new Form of Government was more accepted by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. They approved it in 1645. But because of Cromwell's rise to power, the hope of formally uniting the two churches was lost.

Other Important Documents

While debating church government, the Assembly also created other documents. The Directory for Public Worship, which replaced the Book of Common Prayer, was written quickly in 1644. It was approved by Parliament in January 1645. This Directory was a middle ground between presbyterians and congregationalists. It gave an order for services with sample prayers.

Work on a Confession of Faith (a statement of beliefs) began in August 1646. There were many debates over almost every belief in it. The Confession was sent to Parliament in December. Parliament asked for Bible verses to be added, which were provided in April 1648. Parliament approved the Confession with some changes in June 1648. The Church of Scotland had already adopted it without changes in 1647. But when Charles II became king in 1660, this law was cancelled.

The Assembly also worked on a catechism (a teaching guide). They decided to create two instead of one. The Larger Catechism was for ministers to teach adults. The Shorter Catechism was based on the Larger Catechism but made for teaching children. Parliament also asked for Bible verses for the catechisms. The Scottish Church approved both catechisms in 1648.

The Assembly felt its main work was done by April 1648. The Scottish advisors had already left. The Assembly continued to meet mainly to examine ministers for ordination. Most members were unhappy with the new government that formed after 1648. Many stopped attending rather than agree to a new oath. The Assembly likely stopped meeting around April 1653.

Assembly's Beliefs

The Westminster Assembly followed the British Reformed Protestant tradition. They used the Thirty-Nine Articles and the ideas of James Ussher as main sources. They also connected with other Reformed thinkers in Europe. They believed the Bible was God's authoritative word.

The Confession starts by explaining how people can know about God. The Assembly believed people could learn about God from nature and the Bible. But they also believed the Bible was the only way to truly know God and be saved. They had a strong belief that the Bible was inspired by God. They thought God revealed himself through the ideas in the Bible. They believed the Bible had no errors.

Puritans believed God controls all of history and nature. There was a big debate in the Assembly about how God's plan of predestination (choosing who will be saved) related to Christ's death. Many Reformed thinkers believed Christ died only for those God chose to save. But a few members argued that Christ's death offered salvation to everyone, if they believed. The Confession's language allows for both interpretations.

Covenant theology was an important way Reformed thinkers understood the Bible. The Assembly explained God's dealings with people through two agreements: the covenant of works and the covenant of grace. The Westminster Confession was the first major Reformed document to clearly mention the covenant of works. This idea says that God offered Adam eternal life if he perfectly obeyed. But when Adam sinned, he broke this agreement. To fix this, God offered salvation through the covenant of grace. This allowed people to have eternal life even if they couldn't perfectly obey God's law.

The Assembly members strongly opposed Catholicism. Before the Civil War, they saw Catholics as the biggest threat. But during the war, new radical religious groups appeared. The Assembly became more worried about these groups than about Catholicism.

Lasting Impact

The work of the Westminster Assembly was rejected by the Church of England when the king returned in 1660. A new law in 1662 forced Puritan ministers to leave the church. Even though some presbyterians wanted to rejoin the official church, new rules made it hard for non-conformists to worship. This led presbyterians and congregationalists to work together.

The Civil War ended the idea that England should have only one state-controlled church. This led to the rise of denominationalism, the idea that there can be several true churches in one place.

The Confession made by the Assembly was adopted with changes by Congregationalists in England in 1658. It was also used by Particular Baptists in 1689. When the Church of Scotland's General Assembly was restarted in 1690, it approved the Westminster Confession. Today, the Confession is still the Church of Scotland's main standard, but it is always under the authority of the Bible. Many Presbyterian churches still require children to memorize the Shorter Catechism.

Because these groups spread around the world, the Westminster Assembly's work became very important in English-speaking countries. The Assembly's Confession especially influenced American Protestant beliefs. It was included in the 1648 Cambridge Platform in colonial Massachusetts and the 1708 Saybrook Platform in Connecticut. It was also changed for American Baptists in the 1707 Philadelphia Confession. In 1729, American Presbyterians had to agree to the Assembly's Confession. It is still part of the Presbyterian Church (USA)'s Book of Confessions. One historian called the Confession "the most influential doctrinal symbol in American Protestant history."

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |