Meditations on First Philosophy facts for kids

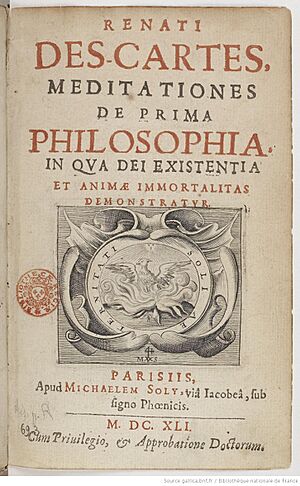

The title page of the Meditations

|

|

| Author | René Descartes |

|---|---|

| Original title | Meditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qua Dei existentia et animæ immortalitas demonstratur |

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Philosophical |

|

Publication date

|

1641 |

|

Original text

|

Meditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qua Dei existentia et animæ immortalitas demonstratur at Script error: The function "name_from_code" does not exist. Wikisource |

| Translation | Meditations on First Philosophy at Wikisource |

Meditations on First Philosophy is a famous book by the French thinker René Descartes. It was first published in Latin in 1641. The full Latin title means "Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are demonstrated."

In this book, Descartes tries to find out what we can know for sure. He starts by doubting everything he thinks he knows. Then, he tries to build up knowledge step by step, based only on things he can be absolutely certain about.

The book is divided into six "meditations." Descartes wrote them as if he was thinking deeply for six days. Each meditation refers to the previous one as "yesterday." This book is one of the most important philosophy texts ever written. People still read it and study it today.

Descartes first shared some of these ideas in his book Discourse on Method (1637). The Meditations goes into much more detail about his ideas on how the world works and what is real.

Contents

Why Descartes Wrote This Book

A Special Message to Smart Thinkers

Descartes wrote a special message at the beginning of his book. It was for the smart professors and thinkers at the University of Paris. He wanted them to protect his work.

He believed it was important to prove that God exists using logic and reason. This way, even people who didn't believe in God could understand his arguments. He also thought that relying only on religious texts might seem like a circular argument. This is because people might say they believe in God because of the Bible, and believe the Bible because God inspired it.

Descartes wanted to show that human minds are capable of discovering God through clear thinking. He hoped his method, which he used for science, could also prove these important truths.

A Note to Readers

Descartes also wrote a note to his readers. He explained that he had talked about God and the soul in his earlier book, Discourse on Method. After that, he received some questions and challenges.

One question was about his idea that the soul is only a "thinking thing." Descartes replied that he clearly felt he was a thinking being. He didn't clearly feel anything else about himself. So, he concluded that the main part of who he is, his "self," is just a thinking thing.

Another challenge was about proving God's existence. Some people said that just because you can imagine something more perfect than yourself, it doesn't mean that perfect thing actually exists. Descartes argued that, in his book, he would show that the idea of something more perfect does mean it must exist.

He also mentioned that people who don't believe in God often make a mistake. They think God is too much like a human, or they think their own minds are so powerful they can fully understand God. Descartes said we should remember that God is endless and impossible to fully understand. Our minds, however, are limited.

Finally, he shared that he let other smart people read his book before it was published. He wanted to hear their questions and challenges. He included their questions and his answers at the end of the book.

How the Book is Structured

Descartes didn't write the book like a textbook with clear sections and chapters. Instead, he wrote it from his own point of view, like a diary. He wanted readers to think along with him as they read. So, the book is like a guide for thinking deeply. It's not just about sharing ideas, but also about having an experience of thinking them through.

Questions and Answers

Before Descartes published Meditations, he sent his writings to many other thinkers. These included philosophers, religious scholars, and logicians (people who study reasoning). He asked them to criticize his work. He wanted to make his arguments as strong as possible. He said, "I will be very glad if people put to me many objections, the strongest they can find, for I hope that the truth will stand out all the better."

The first published version of Meditations included these challenges from other thinkers and Descartes' own detailed answers. There were seven main people or groups who sent him objections.

Some of the most important challenges they raised were:

- About God's Existence:

* Can we truly have a clear idea of something infinite, like God? * Just because we can imagine a perfect being, does that mean it really exists? * Could we have the idea of God without God actually being the cause of that idea? * Can anything create itself? If not, how could God exist if nothing can cause itself?

- About Knowing Things (Epistemology):

* How can we be sure that what we think is a "clear and distinct" idea is truly clear and distinct? * Some argued that Descartes' ideas went in a circle. For example, if we need God to be sure our clear ideas are true, but we use clear ideas to prove God exists, how can we be sure of anything? * Are we really sure that our senses show us the real world? Maybe our minds just create the idea of bodies, and they don't really exist outside of us.

- About the Mind:

* Are ideas always like pictures in our heads? If so, how can we have an idea of a "thinking substance" (the mind) if it's not a picture? * How can we be sure the mind isn't also a physical thing? We don't know everything about the mind, so we can't be sure it's not physical.

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia also wrote to Descartes about his Meditations. She questioned how the mind and body could be connected. She also wondered if moral truths needed more than just the mind to understand them.

Later thinkers have also looked at Descartes' ideas. For example, his idea that a person knows their own mind best has been challenged. Modern psychology shows that our minds and consciousness develop through our interactions with others, language, and culture. Also, the idea that the mind can exist without the body is harder to accept now, given what we know about the brain.

How the Book Changed Thinking

The first two meditations of Descartes' book had a huge impact on philosophy. In these parts, he used a method of doubting everything. He concluded that the only thing he could be sure of was his own existence as a thinking being. This idea was a big step for modern philosophy. Many people see it as a necessary starting point for new ways of thinking.

Some thinkers, like Edmund Husserl, mostly focused on these first two meditations. This suggests they believed these parts were the most important for philosophy.

Other Editions of the Book

Collected Works in French and Latin

- Oeuvres de Descartes, edited by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery, Paris: Léopold Cerf, 1897–1913, 13 volumes; new revised edition, Paris: Vrin-CNRS, 1964–1974, 11 volumes (the first 5 volumes contains the correspondence).

English Translations

- The Philosophical Writings Of Descartes, 3 vols., translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

- The Philosophical Works of Descartes, 2 vols, translated by Elizabeth S. Haldane, and G.R.T. Ross (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

- The Method, Meditations and Philosophy of Descartes, translated by John Veitch (1901)

Single Works

- Six Metaphysical Meditations ..., translated by William Molyneux (1680)

- Méditations Métaphysiques, translated to French from Latin by Michelle Beyssade (Paris: GF, 1993), accompanied by Descartes' original Latin text and the French translation by the Duke of Luynes (1647).

See also

- 17th-century philosophy

- Cartesian Meditations

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |