Alexey Shchusev facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

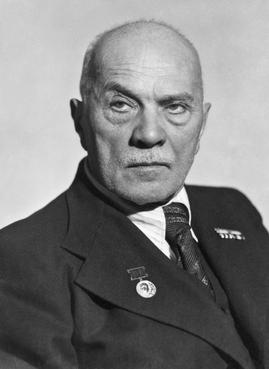

Alexey Shchusev

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 8 October 1873 |

| Died | 24 May 1949 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Russian Empire, Soviet Union |

| Alma mater | Imperial Academy of Arts |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Stalin Prize 1940, 1946, 1948, 1952 |

| Practice | Own practice (1900s–1910s) 2nd Mosproekt Workshop (1932–1937) Akademproekt (1938–1948) |

Alexey Victorovich Shchusev (8 October 1873 – 24 May 1949) was a famous Russian and Soviet architect. He was successful during three different periods of Russian architecture. These included Art Nouveau, Constructivism, and Stalinist architecture.

Shchusev was one of the few architects who was celebrated by both the old Russian Empire and the new Soviet government. He received many Stalin Prizes, which were important awards.

In the early 1900s, Shchusev became known for designing churches. He created a unique style that mixed Art Nouveau with Russian Revival architecture. Before and during World War I, he designed railway stations, like the big Kazansky Rail Terminal in Moscow.

After the October Revolution, Shchusev worked with the new Soviet government. He was chosen to design the Lenin Mausoleum. He built three mausoleums in total: two temporary ones and one permanent one. He also oversaw its expansion in the 1940s.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, he used the Constructivist architecture style. But when the government decided modern styles were not suitable, he switched back to more traditional, historical styles. His career faced some challenges in 1937, but he later returned to his work. He became a leading figure in Stalinist architecture.

Contents

Who Was Alexey Shchusev?

Alexey Shchusev was born in Chișinău (now in Moldova) in 1873. He was the fourth of five children. Both his parents died when he was fifteen. With help from his older siblings and a scholarship, he went to school. His younger brother, Pavel, also became an architect and engineer. Pavel later helped Alexey with bridge projects.

In 1891, Alexey went to the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. He studied both architecture and painting. In 1894, he focused on architecture. Around this time, he designed his first project on a private estate. In 1895, he traveled to Central Asia to study. That same year, he designed a small crypt chapel in a Russo-Byzantine style. He even found his first client in Saint Petersburg by offering his design services to families who had recently lost someone.

In 1896, his last year at the Academy, Shchusev studied old Russian architecture in cities like Kostroma and Yaroslavl. He also studied European architecture in Romania and Austria-Hungary. In 1897, he graduated and married Maria Karchevskaya. He spent the winter of 1897–1898 in Samarkand, studying medieval shrines. This experience with Islamic architecture influenced his later designs. In 1898, he and his wife went on a sixteen-month trip to Europe and Tunisia. He studied for six months in Paris.

What Were Shchusev's Major Architectural Projects?

Designing Churches (1900–1918)

When Shchusev returned to Saint Petersburg, he struggled to find clients. His luck changed in 1901–1902. His design for an iconostasis (a screen with icons) at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra was highly praised. He became a consultant to the Most Holy Synod (a church council). Soon, he helped Mikhail Nesterov with church repairs. Nesterov was impressed and became his supporter.

Shchusev began getting contracts from wealthy families and charities. Over ten years, he became known as a church architect. He moved from historical styles to his own unique "proto-modernist" style. This style mixed Art Nouveau with Russian Revival architecture. His church murals, however, were not as popular.

In 1904, Shchusev was asked to restore a ruined church in Ovruch. His five-domed design in the Byzantine style was debated but approved. The church was rebuilt from 1908 to 1911.

In 1905, he designed a new cathedral at the Pochayiv Lavra. This building, in a medieval style, was completed in 1911. It was a very large structure for its time.

Shchusev's unique style first appeared in a small chapel in Nice (1904–1907). He used ideas from medieval architecture but did not just copy them. Instead, he created his own flowing visual language. This was different from other architects who simply copied old styles. His churches often had a deliberate asymmetry, meaning one side might look different from the other.

One of his best examples of this style is the Saint Basil Monastery in Ovruch (1907–1910). It had a very practical layout and modern forms, even with its old Russian influences. Another striking church was on the Natalievka estate, designed as a private museum for Russian icons.

Perhaps his most famous church is the cathedral of the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent in Moscow (1908–1912). Before World War I, Shchusev also designed churches in Italy, Moldova, and on the Kulikovo Field.

For a long time, Soviet critics avoided calling Shchusev's church designs "Art Nouveau." They presented his work as a unique, patriotic Russian art. Later, experts saw his work as part of the "Neorussian style." This style mixed traditional Russian art with new ideas from Art Nouveau.

Designing Railway Stations (1911–1930s)

In 1911, Shchusev won a competition to design the Kazansky rail terminal in Moscow. His early plans were like his church designs, but the final building was different. He decided to make the long facade (front) look like a series of separate sections. He used the Naryshkin Baroque style, which he studied by visiting old towns. The clock tower was inspired by the Söyembikä Tower and the Borovitskaya Tower, as well as the St Mark's Clocktower in Venice.

The terminal's function was affected by budget cuts. Shchusev wanted a two-story building for better passenger flow, but a cheaper single-story plan was chosen. Construction started in 1913 but was stopped by World War I and the revolutions. The first part of the terminal was finished in 1926, and the western facade in 1940. The last part of the original plan was not built until the 1990s. Shchusev's team also designed nearby service buildings and an elevated viaduct.

From 1914 to 1916, Shchusev also designed smaller railway stations in the Volga region. Many of these followed a standard design inspired by older Baroque styles. Larger stations, like those in Krasnoufimsk and Sergach, used more elaborate Baroque or Empire styles.

The Lenin Mausoleum (1924, 1929–1930, 1940s)

During the Russian Civil War, Shchusev stayed in Moscow and worked with the new Bolshevik government on city planning. By 1921, he was a respected leader among Moscow's architects.

On the night of January 22–23, 1924, Shchusev was called to the Kremlin. He received the most important job of his life: designing the Lenin Mausoleum. The first temporary wooden mausoleum was designed overnight and built in three days, in very cold weather. It was too small, so in March 1924, Shchusev was asked to design a larger temporary structure. This second wooden mausoleum was built in April and opened in August 1924.

Five years later, the government decided to build a permanent mausoleum. Shchusev's early design was asymmetrical, but the government wanted it to look like the wooden one. The final design, built in 1929–1930, was credited to Shchusev and his team.

The design changed during construction. Shchusev wanted the mausoleum to look like a solid block of black stone. But most of the stone was replaced with granite panels over a concrete frame. This created the illusion of solid granite. Like Shchusev's churches, the mausoleum is slightly asymmetrical, though it's hard to notice.

While the exterior of the building became a symbol of Soviet Moscow, much about its underground parts remains unknown. Its internal layout is still secret. The mausoleum was expanded between 1939 and 1946.

Constructivist Buildings (1923–1932)

Around 1923–1924, Shchusev started to use the new constructivism style. He supported this movement publicly. His first building in this style was a club next to the Kazansky terminal. It had a traditional exterior but a modern, open interior.

In 1925, Shchusev entered three major architectural competitions. He designed constructivist proposals for buildings in Kharkiv and Moscow, but he did not win any of them. In 1928–29, he lost another competition to design the Lenin Library. He submitted two designs: one traditional and one very modern, similar to the work of Le Corbusier. Other architects criticized Shchusev for changing his style so much.

Shchusev's first finished constructivist buildings were a sanatorium in Matsesta and a residential building in Moscow, both built in 1928. His largest constructivist design was the Narkomzem Building in Moscow (1928–1933). Shchusev personally managed its construction.

One of his last constructivist buildings in Moscow was the Military Transport Academy (1929–1934). It is considered one of his best modern works. In 1930, he designed two constructivist hotels for Intourist (a state travel agency) in Batumi and Baku.

Early Stalinist Period (1932–1937)

The competition for the Palace of Soviets (1931–1933) marked a big change in Soviet architecture. It moved from modern styles to grand, historical styles. Shchusev's early designs for the Palace were modern, but critics said they "did not look like a palace." He later submitted neoclassical designs. Joseph Stalin chose another architect's design, and was suspicious of Shchusev.

In 1933, Moscow's independent architectural firms became state-owned workshops. Shchusev became the head of the 2nd State Workshop. He led a large team of architects and engineers.

Shchusev was asked to take over and redesign ongoing constructivist projects into a "neoclassical style." This included a large theater in Novosibirsk and the Moscow Hotel. For the Moscow Hotel, Shchusev took full responsibility. The first part of the hotel opened in 1935. Its asymmetrical design was due to incorporating an older building. The theaters in Novosibirsk and Moscow were also completed with Shchusev's influence.

From 1934 to 1936, Shchusev's workshop proposed many grand and varied buildings for Moscow. Only one, the Architects' House, was built. A theater in Tashkent was built later in the 1940s. Shchusev had more success in the Caucasus region. In 1933, he won a competition for the IMEL building in Tbilisi. This project, completed in 1938, became an important example of Stalinist architecture.

Difficult Times and Comeback (1937–1938)

In August 1937, during a difficult political period, Shchusev faced public accusations. He was accused of copying others' work and other professional issues. He lost his leadership positions and was removed from the Union of Soviet Architects. Many of his former colleagues turned against him. Only a few people, like Eugene Lanceray, defended him.

Shchusev disappeared from public life for a while. However, the state did not prosecute him. A few months later, the president of the Academy of Sciences quietly gave Shchusev a contract to design the academy's headquarters. This allowed him to restart his design workshop. The government seemed to give him a second chance.

In July 1938, Shchusev's new workshop became the Akademproekt Institute. This state-owned firm designed various academy projects. Over the next ten years, Shchusev designed academy buildings in Moscow and Almaty. The Akademproekt also received contracts for expanding the Lubyanka Building and the Lenin Mausoleum. After World War II, it focused on top-secret research facilities.

Wartime and Post-War Projects (1941–1949)

After Operation Barbarossa began (Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union), Shchusev was asked to protect the Lenin Mausoleum from air attacks. He decided it was impossible, so Lenin's body was moved to Siberia. Shchusev also worked on a temporary war trophy pavilion in Gorky Park (1941–1942).

In 1942, Shchusev and his team went to Istra, a town damaged by war. He proposed to rebuild Istra as a winter skiing resort. The new city hall, designed by Lanceray, looked similar to Stockholm City Hall. This grand plan was highly publicized, but its full purpose is unclear. Some smaller, less expensive buildings were actually built near the New Jerusalem Monastery.

From 1943 to 1948, Shchusev worked on plans to restore cities like Stalingrad, Veliky Novgorod, and Chișinău. These projects were managed by a special state workshop. The Akademproekt was busy with other projects, including the expansion of the Lenin Mausoleum and the new Lubyanka Building. In 1947, Shchusev tried to get the contract to design the future Hotel Ukraina skyscraper in Moscow, but he did not win.

Shchusev's last major work was the Komsomolskaya–Koltsevaya metro station. He conceived the idea in 1945. The station was designed by Alisa Zabolotnaya and Viktor Kokorin in 1949 and built from 1949 to 1951. It used new steel construction for a very spacious interior. The Baroque style of the station echoed the Kazansky terminal. This design earned Shchusev his fourth Stalin Prize, given after his death in 1952. Some critics later found the design too ornate for a busy transport hub.

In May 1949, Shchusev had a heart attack in Kyiv. He returned to Moscow and died a few days later in a hospital.

How Was Shchusev Remembered?

In his last ten years, Shchusev designed few memorable buildings. However, he received many state awards, including four Stalin Prizes. These awards were for the IMEL building (1940), the Lenin Mausoleum expansion (1946), the Navoi Theater in Tashkent (1948), and the Komsomolskaya-Koltsevaya station (1952). These awards showed the influence of the powerful government agencies he worked for.

After his death, the state honored Shchusev greatly. He was declared the most valuable Soviet architect. His earlier religious and modernist works were often overlooked. Instead, critics focused on his contributions to "socialist realism" in architecture. Even with all the praise, Shchusev still valued practical design and creative freedom more than just grand decorations. He adapted to the strict rules of the time, but he never fully embraced the new "superhuman monumentality" style. Younger architects who fully adopted this style soon surpassed him.

Images for kids

-

Eugene Lanceray. Reconstruction of Istra, main square and city hall. Watercolor, 1942.

See also

In Spanish: Alekséi Shchúsev para niños

In Spanish: Alekséi Shchúsev para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |