Pruitt–Igoe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pruitt-Igoe |

|

|---|---|

The Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and William Igoe Apartments complex

|

|

| Location | St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°38′32.24″N 90°12′33.95″W / 38.6422889°N 90.2094306°W |

| Status | Demolished |

| Area | 57 acres (23 ha) |

| No. of flats | 33 |

| Units | 2,870 |

| Density | 50 units per acre |

| Constructed | 1951–1955 |

| Construction | |

| Architect | Minoru Yamasaki |

| Style | International Style, modern |

| Demolished | 1972–1976 |

The Pruitt–Igoe complex was a large public housing project in St. Louis, Missouri, in the United States. It was made up of two parts: the Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and the William Igoe Apartments. People started moving into the buildings in 1954.

At first, Pruitt–Igoe was seen as a modern solution for housing. But conditions quickly got worse after 1956. By the late 1960s, the complex became known around the world for its poverty, crime, and racial segregation. Most of the people living there were African-Americans. All 33 buildings were torn down using explosives between 1972 and 1976. Pruitt–Igoe is now a famous example of how urban renewal and public housing plans can fail.

The complex was designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki. He also designed the original World Trade Center towers in New York City.

Contents

Why Was Pruitt–Igoe Built?

In the 1940s and 1950s, the city of St. Louis was very crowded. Many homes were old and falling apart. Over 85,000 families lived in 19th-century tenement buildings. These were old, run-down apartment buildings. A survey in 1947 found that 33,000 homes had shared toilets.

Middle-class families, mostly white, were moving out of the city. This is sometimes called "white flight". Low-income families then moved into their old homes. The poor areas of the city were growing. City leaders wanted to fix this problem. They decided to tear down the old slums and build new housing. This idea was called urban renewal.

In 1949, the mayor of St. Louis, Joseph Darst, supported building tall public housing. He believed new projects would help the city. They would bring in more money and create new parks. In 1951, he said: "We must rebuild, open up and clean up the hearts of our cities."

The Housing Act of 1949 helped cities get money for public housing. St. Louis received federal money to build 5,800 new homes. The first large project was Cochran Gardens, built for low-income white families. Pruitt–Igoe was built next. It was meant for young, middle-class white and black families. However, they were put in separate buildings because of racial segregation laws at the time. This segregation ended in Missouri public housing in 1956.

Designing and Building the Complex

In 1950, the city hired a firm to design Pruitt–Igoe. It was named after two St. Louisans: Wendell O. Pruitt, an African-American pilot from World War II, and William L. Igoe, a former US Congressman. At first, the plan was to have separate buildings for black and white residents.

Architect Minoru Yamasaki led the design. This was his first big independent project. His first idea was to mix tall, medium, and short buildings. But federal rules about cost limits changed this. The government agency made them build all 33 buildings at the same height: 11 stories.

An article in Architectural Forum in 1951 praised Yamasaki's original plan. It called it "the best high apartment" of the year. The idea was to build tall so that more ground space could be used for shared activities. This was called "vertical neighborhoods for poor people."

Pruitt–Igoe was finished in 1955. It had 33 buildings, each 11 stories tall. There were 2,870 apartments in total. This made it one of the largest housing projects in the country. The apartments were small, and the kitchens had tiny appliances. The elevators were "skip-stop" elevators. This meant they only stopped on certain floors (1st, 4th, 7th, and 10th). Residents had to use stairs to reach other floors. These "anchor floors" had shared laundry rooms and common areas.

Even with cost-cutting rules, Pruitt–Igoe cost $36 million. This was 60% more than the average for public housing. Some people blamed high wages for workers. Problems with the heating system also caused other parts of the building to be built cheaply.

Despite these issues, Pruitt–Igoe was first seen as a great step forward. Residents often felt it was a big improvement from their old homes. Some even called the apartments "poor man's penthouses."

Why Pruitt–Igoe Declined

In 1955, a judge ordered St. Louis to stop separating people by race in public housing. In 1957, Pruitt–Igoe was 91% full. After that, the number of residents started to drop.

Many residents said that the buildings were not maintained well from the start. Elevators often broke down. Local officials said they did not have enough money to pay for proper upkeep. The buildings also had poor air flow and no central air conditioning.

The stairwells and hallways became dangerous places. People often got robbed there. The "skip-stop" elevators made this worse because people had to use the stairs more often. There were also not enough places for parking or recreation. Playgrounds were only added after residents asked for them.

By 1971, only 600 people lived in 17 buildings at Pruitt–Igoe. The other 16 buildings were empty and boarded up. Meanwhile, a nearby low-rise housing area called Carr Village had similar residents. But it stayed full and had few problems.

Even with the decay and violence, some parts of Pruitt–Igoe worked well. Apartments where only two families shared a landing were often kept clean by the residents. But when many families shared a hallway, these areas quickly became messy. It was hard for anyone to feel responsible for these "no man's lands."

The people living in Pruitt–Igoe also formed a strong tenant association. They created community projects, like craft rooms. Women in Pruitt–Igoe used these rooms to meet, socialize, and make things like quilts to sell.

The Demolition of Pruitt–Igoe

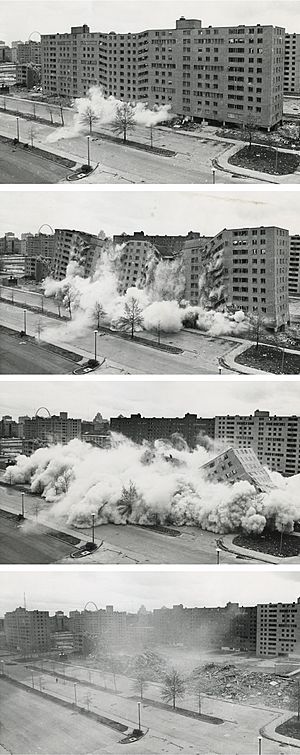

In 1968, the US Department of Housing started to encourage people to leave Pruitt–Igoe. By December 1971, state and federal leaders decided to tear down two of the buildings using explosives. They hoped that reducing the number of people and buildings might make things better. By this time, $57 million had been spent on Pruitt–Igoe.

Authorities thought about different ways to fix Pruitt–Igoe. One idea was to make the tall towers shorter, only four floors high. But in the end, they decided to tear them down.

The first building was demolished with explosives on March 16, 1972. The second building came down on April 21, 1972. More buildings were imploded on June 9. The government then decided not to try and fix the remaining buildings. The rest of the Pruitt–Igoe blocks were torn down over the next three years. The entire site was cleared by 1976.

What We Learned from Pruitt–Igoe

It's hard to say exactly why Pruitt–Igoe failed. Some people say it was a failure of architecture. Even though one magazine praised its design before it was built, Pruitt–Igoe never won any design awards. However, the same architects also designed Cochran Gardens, which did win awards.

Other people say social reasons caused the failure. These include St. Louis losing jobs and people moving to the suburbs. Also, many residents were unemployed, and there was political opposition to government housing. Pruitt–Igoe is now often studied in architecture, sociology, and politics classes. It's seen as a clear example of how the environment affects people's behavior.

Pruitt–Igoe was one of the first times a modern building was torn down. Some historians say its destruction marked "the day Modern architecture died." Its failure is often seen as a problem with the ideas of the International school of architecture. This style aimed to change society through design. But others argue that the location, how many people lived there, cost limits, and even the number of floors were decided by government officials. So, they say the failure wasn't just because of the architecture.

Videos of Pruitt–Igoe being torn down were used in the famous film Koyaanisqatsi.

As of 2020, most of the land where Pruitt–Igoe once stood is still empty. New public schools have been built on one corner of the site. These include Gateway Middle School and Gateway Elementary School, which focus on science and technology. The rest of the site is mostly covered in oak and hickory trees. The old slum areas around Pruitt–Igoe have also been torn down. They have been replaced with smaller, single-family homes.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pruitt-Igoe para niños

In Spanish: Pruitt-Igoe para niños