Pennsylvania Station (1910–1963) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pennsylvania Station

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

View from the northeast in the 1910s

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | New York City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°45′01″N 73°59′35″W / 40.7503°N 73.9931°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | Pennsylvania Railroad Penn Central |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect | McKim, Mead, and White | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Demolished | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | September 8, 1910 (LIRR) November 27, 1910 (PRR) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key dates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | 1904–1910 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demolition | 1963–1968 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pennsylvania Station was a very important train station in New York City. It was built by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) and opened in 1910. People often called it Penn Station for short. The station was huge, covering about 8 acres (3.2 hectares) in Midtown Manhattan. It was located between Seventh and Eighth Avenues and 31st and 33rd Streets.

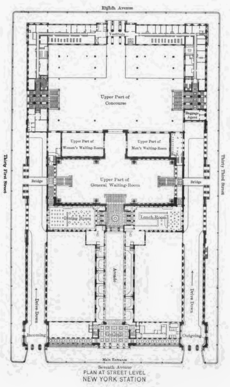

The building was designed by a famous architecture firm called McKim, Mead, and White. It was a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style, which was popular at the time. This style used grand, classical designs. The station had 11 platforms and 21 tracks, similar to the current Penn Station. It was one of the first stations to have separate waiting rooms for people arriving and departing. These rooms were some of the biggest public spaces in New York City when they were built.

After World War II, fewer people traveled by train. In the 1950s, the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the rights to build above the station. This meant the grand building above ground could be torn down. Demolition began in 1963. This loss made many people realize how important it was to save historic buildings. This led to the modern historic preservation movement in the United States. Over the next six years, the underground parts of the station were changed a lot. This became the modern Penn Station. Above it, Madison Square Garden and Pennsylvania Plaza were built. Today, only the underground platforms and tracks, plus a few small pieces, remain from the original station.

History of Penn Station

Why a New York City Train Station?

Before the early 1900s, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) trains stopped in Jersey City, New Jersey. This was on the western side of the Hudson River. Passengers going to Manhattan had to take ferries across the river. Another big railroad, the New York Central Railroad, brought passengers from the north. Their trains ended at Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan.

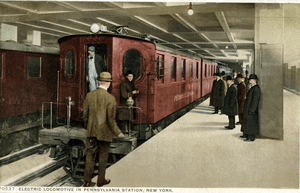

Many ideas for a bridge or tunnel across the Hudson River were suggested in the late 1800s. But these plans didn't work out because of money problems. The PRR thought about building a bridge, but New York State wanted it to be a joint project with other railroads. The other railroads were not interested. Tunnels were another option, but steam locomotives couldn't use them because of smoke. Also, New York State banned steam locomotives in Manhattan after 1908.

Planning the New York Tunnel Extension

In 1901, the PRR found a solution from Paris. In Paris, electric trains were used for the last part of the journey into the city. PRR President Alexander Johnston Cassatt decided to use this idea for New York City. He planned a huge project called the New York Tunnel Extension. This project included:

- New York Penn Station

- The North River Tunnels under the Hudson River

- The East River Tunnels under the East River

The PRR also planned to take control of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). This way, they could build one large train station in Manhattan for both railroads.

The first plan in 1901 suggested a bridge over the Hudson River. It also included two separate stations for the LIRR and PRR. This would let passengers travel between Long Island and New Jersey easily. But in December 1901, the plans changed. The PRR decided to build tunnels under the Hudson River instead of a bridge. Tunnels were much cheaper, costing only a third of a bridge.

The city leaders and other transit companies first opposed the project. But the PRR agreed to some of the city's demands. In December 1902, the New York City Board of Aldermen approved the project. The tunnels would go under the rivers, and the PRR and LIRR lines would meet at the new Penn Station. This "immense passenger station" would be on the east side of 8th Avenue. The whole project was expected to cost over $100 million.

Cassatt's design for Penn Station was inspired by the Gare d'Orsay in Paris. This was also a Beaux-Arts style station. He hired Charles Follen McKim to design the terminal. McKim wanted the station to feel like a grand entrance to a major city. He studied ancient Roman buildings, like the Baths of Diocletian. The original plan was for a station 1,500 feet (457 m) long and 500 feet (152 m) wide. It would have three floors for passengers and 25 tracks.

As part of the plan, the PRR suggested that the United States Postal Service build a post office across from the station. This post office, now the Farley Post Office, was also designed by McKim, Mead & White. The PRR also built a train storage yard in Queens. This yard was for storing train cars and turning locomotives around.

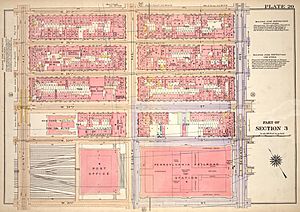

Building the Grand Station

The PRR started buying land for the station in late 1901 or early 1902. They bought a large area between Seventh and Ninth Avenues and 31st and 33rd Streets. This spot was chosen because other areas were too crowded. The main station would be between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. In June 1903, the city started taking ownership of 17 city-owned buildings. By November 1903, all 304 properties in the four-block area were bought. The PRR also bought land for extra tracks and a pedestrian walkway to 34th Street. To make way for the station, about 500 buildings were torn down. This meant thousands of residents, many of them African Americans, had to move.

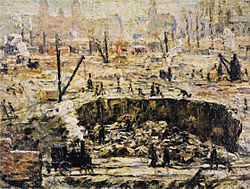

In June 1904, a $5 million contract was given to dig out the site. This was the start of the actual construction. The federal government was still deciding about the post office. The PRR planned to give the land rights above the tracks to the government. Some members of Congress worried the government would only own "a chunk of space in the air." But the Postmaster of New York City, William Russell Willcox, approved the post office. McKim, Mead & White was chosen to design it in 1908.

In June 1906, the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad got permission to run trains to Penn Station from the northeast. They would build a new track to connect to the station. This track, now the Port Morris Branch, would cross the Hell Gate Bridge to Queens. Then it would connect to the East River Tunnels and Penn Station.

The tunnels connecting to Penn Station were very new for their time. The PRR even showed a 23-foot (7 m) section of the East River Tunnels at an exhibition in 1907. The Hudson River tunnels were finished on October 9, 1906. The East River tunnels were finished on March 18, 1908. Workers started laying the stone for the station in June 1908. They finished it 13 months later.

New York Penn Station was officially finished on August 29, 1910. A small part of the station opened on September 8, along with the East River Tunnels. This allowed LIRR riders to travel directly to Manhattan for the first time. Before this, LIRR riders had to take a ferry to Manhattan. The rest of the station opened on November 27, 1910. On its first full day, 100,000 people visited the station. The PRR became the only railroad to enter New York City from the south.

The total cost for the station and tunnels was $114 million. This would be billions of dollars today. The railroad honored Cassatt, who died in 1906, with a statue in the station. It said he achieved "the extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad System into New York City."

How Penn Station Operated

When Penn Station opened, it could handle 144 trains per hour on its 21 tracks. Every weekday, 1,000 trains were scheduled. 600 were LIRR trains, and 400 were PRR trains. LIRR riders' travel times were cut by up to half an hour. The station was so busy that the PRR soon added 51 more trains daily. After the Hell Gate Bridge opened in 1917, New Haven trains also used the station. For 50 years, many long-distance trains arrived and departed daily. They went to cities like Chicago and St. Louis. Penn Station also served trains from the New Haven and Lehigh Valley Railroads. The tunnels made it easier for people to travel from the suburbs. Within 10 years, two-thirds of daily passengers were commuters.

Penn Station gave the Pennsylvania Railroad an advantage over its rivals. Other railroads ended in New Jersey, so travelers had to use ferries to get to New York City. During World War I, the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) also used Penn Station. But the PRR ended the B&O's access in 1926. Penn Station was kept in good condition, which was unusual for a public building. Even the President of the United States used tracks 11 and 12 when arriving in New York.

Over the years, changes were made to increase the station's capacity. The LIRR concourse, waiting room, and platforms were expanded. Connections were added to the New York City Subway stations at Seventh Avenue and Eighth Avenue. The station's electricity system was also updated. By 1935, Penn Station had served over a billion passengers.

A Greyhound Lines bus terminal was built next to Penn Station in 1935. But it soon declined and was used by criminals and homeless people. It also faced competition from the Port Authority Bus Terminal, which opened in 1950. By 1962, the Penn Station bus terminal closed.

The station was busiest during World War II. In 1945, over 100 million passengers passed through it. But after the war, with the rise of air travel and highways, train travel declined. The station also started to look dirty by the 1950s. A renovation in the late 1950s covered some grand columns with plastic. It also blocked the main hallway with a new ticket office. Architect Lewis Mumford wrote in 1958 that "nothing further that could be done to the station could damage it." The station became covered in advertisements, and stores filled the concourses. The beautiful pink granite was stained gray.

The Demolition of Penn Station

In 1954, the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the rights to build above Penn Station to a developer named William Zeckendorf. He suggested building a "world trade center" on the site. This plan allowed the main building and train shed to be torn down. They would be replaced by offices and a sports complex. The underground tracks and platforms would stay, but the station's lower levels would be changed.

Plans for the new Madison Square Garden above Penn Station were announced in 1962. The company that bought the rights, Graham-Paige, would build a new, smaller station underground for free. The Pennsylvania Railroad would also get a share in the new Madison Square Garden Complex. A hotel and office building would be built on the eastern side. The arena would take up most of the block.

One reason given for tearing down the old Penn Station was that it was too expensive to maintain. Its huge size cost a lot of money to keep up. Some people argued that a building meant for function shouldn't be saved just as a monument. As The New York Times wrote, "any city gets what it wants, is willing to pay for, and ultimately deserves." Modern architects tried to save the building. They called it a treasure and chanted "Don't Amputate – Renovate." But despite public opposition, the city decided in January 1963 to start demolishing the station that summer.

Demolition of the above-ground station began on October 28, 1963. A giant steel deck was placed above the tracks. This allowed trains to keep running with few problems. Most of the station's important parts, like the waiting room and platforms, were already underground. About 500 columns were put into the platforms. Madison Square Garden and two office towers were built above the renovated underground areas. The first parts of Madison Square Garden were placed in late 1965. By summer 1966, most of the old station was gone. By late 1966, much of the new station was built. New entrances were added, shops were renovated, and escalators were installed.

The Impact of Demolition

The demolition of Penn Station caused anger around the world. The New York Times wrote that "no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished." They called it a "monumental act of vandalism." A photo of a sculpture from the station lying in a landfill showed how much was lost. This led to efforts to save some of the sculptures. Critics said that tearing down Penn Station was different from other demolitions. Usually, what replaced a building was as good or better.

The controversy over Penn Station's demolition helped start the architectural preservation movement in the United States. In 1965, two years after the demolition began, New York City passed a law to protect landmarks. This created the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. New York City's other main train station, Grand Central Terminal, was also planned for demolition in 1968. But Grand Central Terminal was saved by the Landmarks Commission.

Penn Station Today

The new Penn Station was built underground, beneath Madison Square Garden. It has three levels. The concourses are on the top two levels, and the train platforms are on the lowest level. The concourses were part of the original station but were heavily changed. The tracks and platforms are mostly original. Today, there are separate areas for Amtrak, NJ Transit, and the LIRR.

Many people criticize the modern Penn Station. Architect Vincent Scully said, "One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat." It is often called a "catacomb" because it has low ceilings and lacks charm. This is especially true when compared to the grand Grand Central Terminal. The New York Times called it "the ugly stepchild of the city's two great rail terminals."

In the early 1990s, U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan wanted to rebuild a replica of the historic Penn Station. He suggested building it in the nearby Farley Post Office building. In 1999, Senator Charles Schumer helped pass a law to name the new facility "Daniel Patrick Moynihan Station." This project, now called "Moynihan Train Hall", was built in two parts. The first part opened in June 2017. The second part, which expanded Penn Station into the post office building, opened in January 2021.

Design of the Original Penn Station

The original Pennsylvania Station covered two city blocks. It stretched from Seventh Avenue to Eighth Avenue and from 31st to 33rd Streets. It was 788 feet (240 m) long on the side streets and 432 feet (132 m) long on the main avenues. The station covered 8 acres (3.2 hectares). During construction, over 3 million cubic yards (2.3 million cubic meters) of dirt were dug out. The building used a lot of materials:

- 490,000 cubic feet (13,875 cubic meters) of pink granite

- 60,000 cubic feet (1,699 cubic meters) of interior stone

- 27,000 short tons (24,494 metric tons) of steel

- 48,000 short tons (43,545 metric tons) of brick

- 30,000 light bulbs

When it was finished, The New York Times called it "the largest building in the world ever built at one time."

Outside the Station

The outside of Penn Station had impressive rows of columns. These were based on ancient Roman and Greek designs. The rest of the facade was modeled after famous places like St. Peter's Square in Vatican City. The design combined glass-and-steel train sheds with a grand entrance. The building had entrances on all four sides. Two wide driveways, like Berlin's Brandenburg Gate, led into the station. One was for LIRR trains, and the other for PRR trains. Above each driveway was a 230-foot (70 m) wide colonnade.

The Entrance Arcade

The main entrance was through a shopping arcade. This arcade led west from 7th Avenue and 32nd Street. Two plaques were at the Seventh Avenue entrance. One listed the names of people who led the New York Tunnel Extension project. The other had dates and contractor names. Cassatt wanted passengers to have a special experience when they arrived. He designed the arcade with high-end shops, like those in Milan and Naples. The arcade was 45 feet (14 m) wide and 225 feet (69 m) long. The entrance to this arcade was considered the grandest. Its colonnade was 35 feet (11 m) above the ground. The columns supporting it were 4.5 feet (1.4 m) wide.

At the western end of the arcade, a statue of Alexander Johnston Cassatt stood in a niche. Wide stairs led down to a waiting room. A statue of PRR president Samuel Rea was also installed in 1930.

Inside the Station

The huge waiting room stretched the entire length of Penn Station. It had long benches, smoking lounges, newspaper stands, phones, and baggage windows. This main waiting room was inspired by the Baths of Diocleziano in Rome. It was 314 feet 4 inches (95.8 m) long, 108 feet 8 inches (33.1 m) wide, and 150 feet (46 m) tall. It had three large semicircular windows on each wall. Each window had a radius of 38 feet 4 inches (11.7 m). With these dimensions, Penn Station was the largest indoor space in New York City. It was also one of the largest public spaces in the world.

Penn Station was one of the first train stations to separate arriving and departing passengers. The main concourse for departing passengers was next to the waiting room. It was even larger, at 314 feet 4 inches (95.8 m) long by 200 feet (61 m) wide. This concourse had glass domes supported by a steel frame. LIRR trains used the northernmost four tracks. PRR trains used the southernmost tracks. They shared the center tracks when needed. LIRR commuters could also use an entrance on 34th Street. There was another level below the main concourse for arriving passengers. It had two smaller concourses, one for each railroad.

At platform level, there were 21 tracks and 11 platforms. The station could handle up to 144 trains per hour. About 4 miles (6.4 km) of storage tracks could hold up to 386 train cars. The station had 25 elevators for baggage and passengers. The storage yards were located between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. The building above was supported by 650 steel columns. East of the station, the tracks merged into tunnels under the East River. West of the station, all 21 tracks merged into the two North River Tunnels. Four control towers managed train movements. Tower A, the main one, still exists today under the Farley Post Office.

Art and Decorations

Artist Jules Guérin created six murals for Penn Station. Each was over 100 feet (30 m) tall. The station also had four pairs of sculptures by Adolph Alexander Weinman, called Day and Night. These sculptures, based on model Audrey Munson, were next to large clocks on each side of the building. The Day and Night sculptures had two small stone eagles each. There were also 14 larger, freestanding stone eagles on the outside of Penn Station.

What Remains Today

After the original Penn Station was torn down, many of its parts were lost or buried. But some pieces were saved and moved. Other parts are still in the current station, either covered up or visible.

Ornaments and Art Pieces

We know where all 14 of the larger eagle sculptures are today.

- Three are in New York City: two at Penn Plaza and one at Cooper Union.

- Three are on Long Island: two at the United States Merchant Marine Academy and one at the LIRR station in Hicksville, New York.

- Four are on the Market Street Bridge in Philadelphia.

- Individual eagles are in Farmville, Virginia, Washington, D.C. (at the National Zoo), Vinalhaven, Maine, and Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

Of the eight smaller eagles, four have been found. Two are at Skylands in Ringwood, New Jersey. The other two are part of the Eagle Scout Memorial Fountain in Kansas City, Missouri.

Three pairs of the Day and Night sculptures have been found. One complete pair is at Kansas City's Eagle Scout Memorial Fountain. A Night sculpture was moved to the sculpture garden at the Brooklyn Museum. Another pair was found in a parking lot in Newark, New Jersey. A Day sculpture was found damaged in the Bronx in 1998.

The Brooklyn Museum also has part of one of the station's columns and some plaques. The largest saved piece is a 35-foot (11 m) Doric column. It was moved to Woodridge, New York, around 1963 for a college that was never built. It was too hard to move it back. Eighteen columns were supposed to go to Battery Park in Lower Manhattan. But they were dumped in a landfill in New Jersey instead.

The statue of Samuel Rea still exists. It is outside the modern Penn Station entrance on Seventh Avenue.

Remaining Layout Features

Some small architectural details remain in the station. Some of the original staircases to the platforms, with brass and iron handrails, are still there. Original granite can sometimes be seen where modern flooring has worn away. The current waiting areas and ticket booths are in roughly the same places as the original ones. Parts of the northern entrance driveway also still exist. The modern station still uses the original structure underneath. From the platform level, you can still see glass vault lights in the ceiling. These once let light from the original train shed shine down to the concourse.

Penn Station Services Building

The Penn Station Services Building is just south of the station. It is at 242 West 31st Street. It was built in 1908 to provide electricity and heat for the station. The building is 160 feet (49 m) long and 86 feet (26 m) tall. It has a pink granite front in the Roman Doric style. It was also designed by McKim, Mead and White.

This building survived the demolition of the main station. But it was changed to only provide compressed air for the train switches. In 2020, a plan was suggested to expand Penn Station south. This would be called Penn South. It would require tearing down the block where this building is located.

Penn Station in Movies

The 1945 film The Clock has scenes that are supposed to be in Pennsylvania Station. But they were actually filmed on a movie set. The 1951 Alfred Hitchcock film Strangers on a Train has a chase scene in Pennsylvania Station. This scene shows its grand central terminal.

Pennsylvania Station was also recreated for a scene in the film Motherless Brooklyn. They used special effects, a real set, and actors in old-fashioned clothes. The movie showed the station as it looked in the 1920s and 1930s, not its more run-down look by the film's 1957 setting.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Estación Pensilvania (1910-1963) para niños

In Spanish: Estación Pensilvania (1910-1963) para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |