Émile Ollivier facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

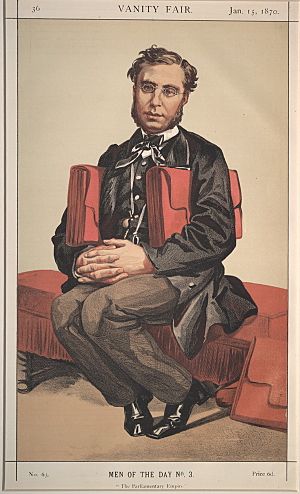

Émile Ollivier

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 27 December 1869 – 9 August 1870 |

|

| Monarch | Napoleon III |

| Preceded by | Personal rule of Napoleon III between 1852 and 1869. Previous Prime Minister: Léon Faucher (1852) |

| Succeeded by | Charles Cousin-Montauban, Comte de Palikao |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Olivier Émile Ollivier

2 July 1825 Marseille, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 20 August 1913 (aged 88) Saint-Gervais-les-Bains, France |

| Political party | None |

| Spouses |

Blandine Liszt

(m. 1857; died 1862)Marie-Thérèse Gravier

(m. 1869) |

| Children | 4 |

Olivier Émile Ollivier (born July 2, 1825 – died August 20, 1913) was an important French politician. He started his career as a strong supporter of a republic, which meant he was against Emperor Napoleon III.

However, Ollivier later worked to convince the Emperor to make France more free and democratic. He eventually became a key government leader, serving as the prime minister just before Napoleon III's rule ended.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Émile Ollivier was born in Marseille, a city in France. His father, Démosthène Ollivier, was a strong opponent of the king's rule at the time, known as the July Monarchy.

In 1848, his father was elected to the assembly that created the Second Republic (a government without a king). Because his father was against Louis Napoleon (who later became Emperor Napoleon III), he was sent away from France in 1851. He could only return in 1860.

Starting in Government

When the Second Republic was formed, Émile Ollivier's father helped him get a job as a high-ranking official in the Bouches-du-Rhône area. Ollivier was only 23 years old and had just become a lawyer in Paris.

He was not as extreme in his political views as his father. He helped stop a workers' uprising in Marseille, which impressed General Cavaignac. This general then made Ollivier the head official, or prefect, of the area.

Later, he was moved to a less important job, possibly because of his father's enemies. Ollivier then left government work to focus on his law career, where he became very successful.

Pushing for a Liberal Empire

In 1857, Ollivier returned to politics as a representative for the Seine area. He joined a group of politicians who wanted to change the government.

He and four other politicians formed a group called Les Cinq (The Five). They worked hard to get Emperor Napoleon III to allow more freedoms and a more constitutional government.

Working with the Emperor

Even though Ollivier was a republican, he was willing to work with the Empire if it meant gaining more civil liberties for the people. He believed these changes could happen step by step.

In November 1859, the Emperor made a new rule that allowed parliamentary reports to be published. This was a big step towards a more open government, and Ollivier welcomed it.

Over time, Ollivier started to move away from his old republican friends. By 1866, he formed a new group that supported the idea of a "Liberal Empire." This meant an empire that still had an emperor but also gave more rights and power to the people and their elected representatives.

In 1866, Ollivier was offered a job as the Minister of Education. However, he refused because he felt the Emperor's promises for freedom of the press and public meetings were not enough.

Leading the Government

Before the 1869 elections, Ollivier wrote a public statement about his political goals. In September 1869, a new law gave the two parts of the parliament more power. This led to a new government being formed in December, with Ollivier as the main leader, even though he wasn't officially called "prime minister."

Challenges and Reforms

This new government, called the "ministry of 2 January," faced many challenges. A week after it was formed, a republican journalist named Victor Noir was shot by Prince Pierre Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor's cousin.

Ollivier quickly brought the Prince to court. He also made sure that riots after the shooting were stopped peacefully. He sent out rules to government officials, telling them not to pressure voters. He even fired a powerful official named Baron Haussmann.

To stop strong criticism of the Emperor in the newspapers, Ollivier took legal action against some journalists. On April 20, 1870, a new law officially changed the Empire into a constitutional monarchy. This meant the Emperor's power was limited by a constitution and a parliament.

Public Vote and Resignations

Even with these changes, some opposition groups were not happy. However, on May 8, 1870, the new constitution was put to a public vote (a plebiscite). Nearly seven out of ten people voted in favor of the government. This seemed to confirm that Napoleon III's son would become the next emperor, which was a big disappointment for those who wanted a republic.

Some important members of Ollivier's government resigned in April because they disagreed with the plebiscite. Ollivier himself took over as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for a month. Other empty positions were filled by more conservative politicians.

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871)

In early 1870, a new problem arose: a German prince, Leopold of Hohenzollern, was considered for the throne of Spain. This upset Ollivier's plans.

The French government, following advice from its foreign minister, told their ambassador to Prussia to demand that the Prussian king officially reject the prince's claim to the Spanish throne.

War Declared

Ollivier was convinced by those who wanted war. It's possible he couldn't have stopped the war, but he might have delayed it. He was outsmarted by Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian leader.

On July 15, Ollivier quickly announced to the parliament that the Prussian government had insulted the French ambassador. He then got approval for a large amount of money for the war. He famously said he accepted the responsibility for the war "with a light heart," claiming France was forced into it.

End of Ollivier's Government

By August 9, the French army had lost three battles in just three days. As a result, Ollivier's government was forced out of office. Ollivier himself had to leave France and went to Italy to escape public anger.

He returned to France in 1873, but his political influence was gone. Even within his own political group, he faced disagreements.

Personal Life

Émile Ollivier had many connections with artists and writers. He was one of the first people in Paris to support the famous composer Richard Wagner.

In 1870, he was elected to the French Academy, a very respected group of scholars. His first wife, Blandine Rachel Liszt, was the daughter of the famous musician Franz Liszt. They had one son, Daniel. Blandine died in 1862. In September 1869, Ollivier married Marie-Thérèse Gravier, who was 19 years old. They had three children together.

Writings

During his retirement, Ollivier spent his time writing a history book called L'Empire libéral (The Liberal Empire). The first part came out in 1895. This large work explained the reasons for the Franco-Prussian War and was also Ollivier's way of defending his actions.

The book, which eventually had 18 volumes, showed that the blame for the war couldn't be placed entirely on him. L'Empire libéral is considered an important document for understanding the history of his time.

- Vol. 1 (1895): le principe des Nationalités (online)

- Vol. 2 (1897): Louis-Napoléon et le coup d' état (online)

- Vol. 3 (1898): Napoléon III (online)

- Vol. 4 (1899): Napoléon III et Cavour (online)

- Vol. 5 (1900): L'Inauguration de l'Empire libérale roi Guillaume (online)

- Vol. 6: La Pologne; les élections de 1863, la loi des coalitions (online)

- Vol. 7 (1903): Le démembrement du Danemark; Le syllabus; La mort de Morny; L'entrevue de Biarritz (online)

- Vol. 8 (1903): L' Année fatale – Sadowa (1866) (online)

- Vol. 9 (1904): Le Désarroi (online)

- Vol. 10 (1905): l' Agonie de l' Empire autoritaire (online)

- Vol. 11 (1907): La veillée des armes. L'affaire Baudin. Préparation militaire prussienne. Le plan de Moltke. Réorganisation de l'armée française par l'empereur et le maréchal Niel. Les élections en 1869. L'origine du complot Hohenzollern (online)

- Vol. 12 (1908): Le ministère du 2 janvier. Formation du ministère. L'affaire Victor Noir. Suite du complot Hohenzollern. (online)

- Vol. 13 (1909): Le guet-apens Hohenzollern. Le concile œcuménique. Le plébiscite (online)

- Vol. 14 (1909): La guerre. Explosion du complot Hohenzollern. Déclaration du 6 juillet. Retrait de la candidature Hohenzollern. Demande de garantie. Soufflet de Bismarck. Notre réponse au soufflet de Bismarck. La déclaration de guerre (online)

- Vol. 15 (1911): Étions-nous prêts? Préparation. Mobilisation. Sarrebruck. Alliances (online)

- Vol. ..... Premier acte: Woerth. Forbach. Renversement du ministère (online)

- Vol. 17 (1915): La fin (online)

- Vol. 18 (1918): Table générale et analytique (online)

- The Franco-Prussian War and its hidden causes (1913, online)

His other works include:

- Démocratie et liberté (1867, online)

- Le Ministère du 2 janvier, mes discours (1875)

- Principes et conduite (1875)

- L'Eglise et l'Etat au concile du Vatican (2 vols., 1879)

- Solutions politiques et sociales (1893)

- Nouveau Manuel du droit ecclésiastique français (1885).

See also

In Spanish: Émile Ollivier para niños

In Spanish: Émile Ollivier para niños