History of York facts for kids

The city of York in England has a very long and interesting history, going back thousands of years! People lived in this area as early as 8,000 to 7,000 years BC. When the Romans arrived, they called the city Eboracum. Later, the Angles changed the name to Eoforwīc, which meant "wild-boar town." Even later, the Vikings called it Jórvík, meaning "wild-boar bay." Today, the Welsh name for York is Efrog.

After the Angles settled in northern England, York became an important capital. First, it was the capital of a kingdom called Deira. Then, it was a key city for the kings of Northumbria in the early 600s. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, York was badly damaged. But it grew back to be a very important city. It became the main administrative center for the county of Yorkshire. York did very well during the later Middle Ages, especially in the late 1300s and early 1400s.

During the English Civil War, York was a strong supporter of the King. It was attacked and eventually captured by Parliament's forces in 1644. After the war, York remained a top city in the North. By 1660, it was the third-largest city in England, after London and Norwich. Today, York has many protected areas and historic buildings. Thousands of visitors come every year to see its amazing Roman, Viking, medieval, and Georgian buildings.

Contents

Ancient Times: Early Settlements

Archaeologists have found signs that people lived in the York area between 8,000 and 7,000 BC. We don't know if they lived there all the time or just visited. Later, during the Stone Age (Neolithic period), people used polished stone axes. These have been found near the River Ouse, where York is now.

Evidence from the Bronze Age shows people continued to live here. They left behind flint tools, weapons, and bronze items. A special pot from the Beaker culture was also found. During the Iron Age, burials have been discovered near the River Ouse. A farm from the late Iron Age was found a few miles away at Naburn.

Roman Eboracum: A Powerful City

The Romans called the local tribes around York the Brigantes and the Parisii. York might have been on the border between these two groups. When the Romans took over Britain, the Brigantes first became allies. But when their leaders turned against Rome, a Roman general named Quintus Petillius Cerialis led his army, the Ninth Legion, north.

York was founded in 71 AD. Cerialis and the Ninth Legion built a military fort on flat land next to the River Ouse. This fort was later rebuilt with stone. It was huge, covering 50 acres, and housed 6,000 soldiers! The earliest mention of York by its Roman name, Eburaci, is from a wooden writing tablet found at another Roman fort. Much of the Roman fort in York is now under the famous York Minster church. Digs under the Minster have shown parts of the original Roman walls.

Around 109 to 122 AD, the Ninth Legion was replaced by the Sixth Legion. No one knows what happened to the Ninth Legion after 117 AD. The Sixth Legion stayed in York until the Romans left Britain around 400 AD. Important Roman Emperors like Hadrian, Septimius Severus, and Constantius I all visited York. Emperor Severus even made York the capital of a Roman province called Britannia Inferior. He likely gave York the special status of a "colonia," which meant it was a city with special rights. Constantius I died in York, and his son, Constantine the Great, was declared Emperor by the soldiers there.

The army was very important for York's economy. Workshops grew up to supply the 5,000 soldiers. They made pottery, tiles, glass, and metal goods. Local people also started a civilian town across the River Ouse from the fort. By 237 AD, this civilian town also became a "colonia." York was self-governing, run by a council of rich local people, including merchants and retired soldiers.

Signs of Roman religious beliefs have been found in York. These include altars to Roman gods like Mars, Hercules, Jupiter, and Fortune. The most popular gods were the spirits of York itself and the Mother Goddesses. There was also a Christian community in York, though we don't have many archaeological signs of it. We know about it because a bishop from York, Eborius, attended an important Christian meeting in 314 AD.

By 400 AD, York faced problems. The city often flooded from the Rivers Ouse and Foss. Its docks were buried under mud, and the main Roman bridge might have fallen apart. York was probably no longer a big population center, though it may have remained a place of authority. The "colonia" part of the city, which was higher up, was also mostly abandoned.

Early Middle Ages: From Roman to Anglo-Saxon York

After the Romans: Ebrauc

After the Romans left Britain in 410 AD, there isn't much written about York for a few centuries. This was common across Britain. However, archaeologists have found signs that people continued to live in York near the River Ouse in the 400s. Some Roman houses were still lived in after the Romans left.

Some historians think York remained an important regional center for the Britons. An old text from around 830 AD lists "fortified cities," and one of them is called Cair Ebrauc, which refers to York. This suggests York continued to be important. One scholar, Christopher Allen Snyder, says that York might have been a military outpost or the center of a small kingdom. However, another historian, Nick Higham, believes the settlement had shrunk so much that it was unlikely to be a major center.

Anglo-Saxon Eoforwic: A Royal City

Angles, a Germanic people, settled in the York area in the early 400s. Their cemeteries from this time have been found nearby. It's not clear if York itself was settled much during this early period. The Roman fort was probably not used as a base against the Angles. The flooded areas were not fixed until the 600s. After the Angles settled, York became the capital of the kingdom of Deira. Later, when Deira joined with another kingdom to form Northumbria, York was one of its capitals.

By the early 600s, York was a very important royal city for the Northumbrian kings. This is where Paulinus (later Saint Paulinus) came to build his wooden church, which was the first version of York Minster. King Edwin of Northumbria was baptized here in 627.

For centuries, York remained a key royal and church center. It was the home of a bishop, and from 735, an archbishop. We don't know much about Anglo-Saxon York from written records. But we do know that the Minster was built and rebuilt. York also became a center for learning, with a famous library and school. Alcuin, who later advised the great leader Charlemagne, was a student and teacher there.

Archaeological digs show that the Roman fort walls likely survived. The Anglian Tower, a small square tower, might have been built to fix a gap in the Roman wall. This shows that the Roman street plan probably survived inside the fort. Digs under York Minster show that the great hall of the Roman headquarters was still used until the 800s.

By the 700s, York was a busy trading center. It had links with other parts of England, France, the Netherlands, and Germany. Buildings from the 600s and 800s have been found near the Rivers Foss and Ouse. This suggests a trading settlement grew along the rivers, separate from the old Roman center.

Viking Jórvík: The Wild-Boar Bay Kingdom

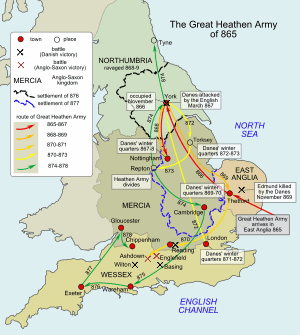

In November 866 AD, a large army of Danish Vikings, known as the "Great Heathen Army," captured York. They took the city easily because the Northumbrian kingdom was fighting among itself. The next year, the Vikings held the city when the Northumbrians tried to take it back. The army left later that year, putting a local puppet king in charge of York.

The Viking army returned in 875, and their leader Halfdan took control of York. From York, Viking kings ruled an area that historians call "The Kingdom of Jorvik." Many Danes moved to and settled in this kingdom and in York itself. A Viking royal palace might have been located where King's Square is today, near the old Roman fort. In 954, the last Viking king, Eric Bloodaxe, was forced out. His kingdom then became part of the newly united Anglo-Saxon state of England.

Several churches were built in York during the Viking Age. These include St Olave's, built before 1055, and St Mary Bishophill Junior, which has a tower from the 900s.

Medieval York: Castles, Guilds, and Walls

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, York was severely damaged by William the Conqueror. He attacked the North to stop rebellions. Two castles were built in the city, one on each side of the River Ouse. Over time, York became a very important city again. It was the administrative center for Yorkshire, the home of an archbishop, and sometimes even a second seat for the king's government. It was also a major trading hub.

Many religious houses were founded after the Conquest, including St Mary's Abbey. York also had a large Jewish community, protected by the sheriff. However, on March 16, 1190, a mob forced the Jews in York to hide in the castle keep. The castle was set on fire, and many Jews were killed. This happened during a time when Jews were being attacked in many parts of Britain. The Jewish community in York did recover, but Jews were later expelled from England in 1290.

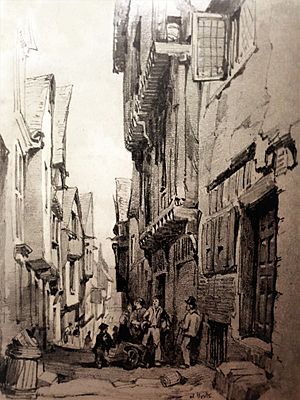

York did very well during much of the later medieval period. Twenty-one medieval churches still exist today, though only a few are regularly used. Many old timber-framed buildings also survive. While some old medieval areas were removed in the 1800s, streets like The Shambles are still here. The Shambles mostly dates from the later medieval era. It has many timber-framed shops with upper floors that hang over the street. It was originally a street for butchers but is now a popular tourist spot with souvenir shops. Some shops still have the outdoor shelves and hooks where meat was displayed.

The medieval city walls, with their entrance gates called "bars," surrounded almost the entire city and are still standing today. York was also made a "county corporate," which gave it the same status as a county.

The late 1300s and early 1400s were especially prosperous for York. This is when the famous York Mystery Plays began. These were religious plays performed by different craft guilds. Important people from this time included Nicholas Blackburn, who was Lord Mayor in 1412. He was a leading merchant. York's importance in the region seemed to decline a bit after the late 1400s. The building of the city's new Guildhall around the mid-1400s might have been an effort to show the city's confidence.

Early Modern York: Changes and Conflicts

Few important buildings were built in the century after York Minster was finished in 1472. Exceptions include the King's Manor, which housed the Council of the North, and the rebuilding of St. Michael le Belfrey church. Guy Fawkes, famous for the Gunpowder Plot, was baptized there in 1570.

During the time when monasteries were closed in England, all the monastic institutions in York were shut down. This included St. Leonards Hospital and St. Mary's Abbey in 1539. In 1547, fifteen parish churches were closed, reducing the number from forty to twenty-five. This showed that the city's population was shrinking. Even though practicing Catholicism became illegal, a Catholic community secretly remained in York. One famous member was St. Margaret Clitherow, who was executed in 1586 for hiding a priest.

In 1642, King Charles I set up his court in York for six months. Later, during the English Civil War, York was a strong supporter of the King. It was attacked and captured by Parliament's forces in 1644. After the war, York slowly became important again in the North. By 1660, it was the third-largest city in England.

In 1686, the Bar Convent was founded in secret because of anti-Catholic laws. It is the oldest surviving convent in England. York also elected two members to Parliament. The Judges Lodgings, a beautiful townhouse built between 1711 and 1726, was used to house judges when they visited York Castle.

On March 22, 1739, a famous lawbreaker named Dick Turpin was found guilty of stealing horses in York. He died on April 7, 1739. Turpin is buried in the churchyard of St George's Church. In 1740, York's first hospital, York County Hospital, opened. It was funded by public donations.

Modern York: Railways and Recovery

| York population 1801–2001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Data for UK Census results for York UA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1796, a Quaker named William Tuke founded The Retreat. This was a hospital for people with mental health conditions. It was located outside the city walls and used a kind of therapy called "moral treatment."

The Yorkshire Museum opened in 1830. The British Association for the Advancement of Science held its first meeting there in 1831. York became a major railway center in the 1800s, thanks to "Railway King" George Hudson. It kept this status well into the 1900s.

On April 29, 1942, York was bombed by German planes during World War II. This was part of the "Baedeker Blitz." 92 people were killed, and hundreds were hurt. Buildings like the Railway Station, Rowntree's Factory, and the Guildhall were damaged. The Guildhall was completely destroyed and rebuilt later.

During the Cold War, a special bunker was built in York for the Royal Observer Corps. It opened in 1961 and was used until 1991. Now, it's a museum. In 1971, York became an army Saluting Station, firing gun salutes five times a year. This marked 1900 years of the army being in York. The University of York opened in 1963. In 1975, the National Railway Museum opened near the city center.

In October and November 2000, the River Ouse flooded very badly. Over 300 houses in York were flooded, but thankfully no one was seriously hurt.

Images for kids

-

Men outside a shop in St Helen's Square around 1910

-

The Yorkshire Museum in around 1910

-

Low Petergate looking toward Bootham Bar in around 1910

See also

- Timeline of York

- History of Yorkshire

- Medieval churches of York

- Religion in York

- Walker Iron Foundry