Jérôme Pasquier (courtier) facts for kids

Jérôme Pasquier was a French servant who worked for Mary, Queen of Scots. His job involved writing and understanding secret coded letters.

Contents

Working for a Queen in Custody

Jérôme Pasquier was a "groom of the chamber" for Queen Mary. This meant he was a personal attendant. He also managed her clothes and belongings as "master of her wardrobe." Other grooms included Bastian Pagez. People called him "young Pasquier." One person described him as a clerk and treasurer, someone who handled money.

Pasquier might have joined Mary's service through Albert Fontenay. Fontenay was the brother of Mary's secretary, Claude Nau.

In March 1586, Pasquier and Bastian Pagez witnessed a document at Chartley Castle. This document was about Mary's surgeon, Jacques Gervais. It put his affairs in the hands of Jean de Champhuon. Champhuon managed Mary, Queen of Scots' properties in France.

Handling Secret Letters

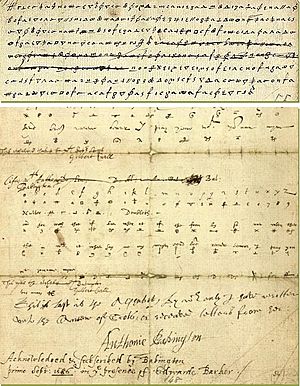

Pasquier worked closely with Mary's secretaries, Claude Nau and Gilbert Curle. They managed all of Mary's letters. Letters written in code, called "cipher," came to him from the French ambassador in London, Guillaume de l'Aubespine de Châteauneuf. In May 1586, Mary said she received many coded letters. Curle would translate Mary's French ideas into English and then put them into code. Nau handled the French letters.

In August 1584, Pasquier helped decode a long letter for Mary and Claude Nau. It was from Albert Fontenay. The letter described Fontenay's visit to Scotland and his talks with King James VI. This letter described the young king and his hobbies. It is now an important source of information about him. Pasquier also decoded another letter from Fontenay in November 1584. This letter talked about King James VI's thoughts on a plan to invade England. Pasquier even decoded a letter in Spanish for Mary in 1585. It was from Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma.

In November 1584, Pasquier went to London with Nau. Nau was acting as Mary's diplomat, meaning he represented her. They borrowed money from other people in Mary's household. Pasquier said he first heard about the Throckmorton plot during this trip. In June 1586, Nau sent Pasquier to Amias Paulet. Nau complained that Mary's letters should be sent right away. They should not have to wait for someone to carry them.

Mary used secret codes for her letters. She mentioned this in a letter in August 1571. This was before Pasquier joined her service. Drafts of coded letters were usually burned for safety. This was in case her letters were taken or her belongings searched.

Arrested and Questioned

The Babington Plot was a plan to free Mary and put her on the English throne. When this plot was discovered by Francis Walsingham, Pasquier was arrested in August 1586. Mary's secretaries were also arrested. Amias Paulet suggested arresting Pasquier, saying he was "half a secretary." Pasquier was moved to a house at Chartley Castle. Walsingham told Paulet to send Pasquier to London under "sure guard." Pasquier was taken to the Tower of London on August 29, escorted by three men.

Pasquier's Confession

Pasquier was questioned twice in September 1586. The people questioning him included Owen Hopton and the code expert Thomas Phelippes. They showed him examples of his coded work. Pasquier admitted to writing and copying coded letters for Mary. He said that Nau was in charge of the secret code keys. The code work happened in Nau's room. Pasquier delivered the finished coded and decoded letters to Mary or Nau. He claimed he could not remember what the letters said. But he did remember encoding a letter for Mary in 1584. It was sent to the French ambassador Michel de Castelnau. Mary asked him to help Francis Throckmorton after his trial for treason.

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley suggested threatening Nau, Curle, and Pasquier. The idea was to make them confirm Mary's involvement. This would help them escape punishment. Claude Nau said that some important letters were kept in Pasquier's chests. These letters were copied in French and English. Finding proof of Mary's involvement in treasonous letters was important. But it was hard to prove she wrote the coded messages herself. Mary denied writing to Anthony Babington with her own signature. She questioned if any letters were truly hers.

Walsingham sent news to the Royal Court of Scotland in September 1586. He said Mary would be moved to Fotheringhay Castle. He also said that "the matters whereof she is guilty are already so plain and manifest (being also confessed by her two secretaries), as it is thought, they shall required no long debating." This meant her guilt was clear, and her secretaries had confessed.

Pasquier signed a confession on October 8, 1586. He was called Mary's "argentier," or money handler. He said he coded and decoded letters. These letters were sent to people like the Archbishop of Glasgow, Albert Fontenay, Thomas Morgan, and French ambassadors. Nau gave Pasquier the drafts of the letters he had written. Pasquier knew little about a plan for Mary's allies to invade England. He said it was put off because of changing political situations.

Pasquier's statements were not directly used in Mary's treason trial. The focus was on a letter sent to Babington by Nau. This was called the "bloody letter." A code used to write to him was also found in Mary's papers. Pasquier had a smaller role in Mary's letters than Nau and Curle. He mostly coded drafts from Nau or decoded incoming letters.

After Mary's Trial

French diplomats thought Mary might not be executed. Guillaume de l'Aubespine de Châteauneuf believed Pasquier would be set free. He thought Pasquier would return to Mary and tell her about efforts to help her. Then Pasquier could advise Mary to write apology letters to Elizabeth. However, Mary was executed on February 8, 1587. Pasquier remained in custody.

Pasquier was still in charge of some household accounts. He also managed the distribution of cloth for clothes in Mary's household. He wrote about these money matters in January 1587. Mary later came to distrust Pasquier and Nau. She thought they had betrayed her. She removed them from her will. She also wrote a note about her concern over money Pasquier received. Mary wrote from Fotheringhay Castle that she feared they had sped up her death.

Pasquier and the two secretaries were released in August 1587. This was after Mary's funeral. They were given papers to return home. Pasquier carried a letter from the French ambassador to the King of France. This letter included a short description of Mary's funeral.