Jean Ricardou facts for kids

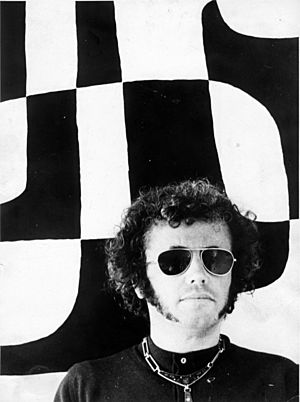

Jean Ricardou (born June 17, 1932, in Cannes, France – died July 23, 2016, in Cannes) was a French writer and thinker. He was known for his novels and his ideas about how writing works.

He joined the Tel Quel group, which was a famous literary magazine, in 1962 and wrote for them until 1971. Between 1961 and 1984, he wrote three novels, a collection of short stories, and four books about literary theory. He also created a "mix" of fiction and theory.

Jean Ricardou was the main thinker behind a French literary movement called the New Novel. After 1985, he focused almost entirely on creating a new way to study writing, which he called "textics."

After he passed away, all of Jean Ricardou's works (called L'Intégrale) began to be published by a company in Belgium called Les Impressions nouvelles.

Contents

- From Teacher to Writer

- Ricardou's Fiction

- Ricardou's Theories

- Complete Works (in French): Published After His Death

- Works of Fiction (Novels and Short Stories)

- Fiction (in English)

- Critical Theory (Books)

- Critical Theory (in English)

- Mix (of Theory, Fiction, Poetry, etc.)

- Textics

- About Textics (in English)

From Teacher to Writer

Jean Ricardou believed that to understand a book, you should focus on the text itself, not on the author's life. After finishing college in 1953, he taught reading and writing to young boys. Later, he taught literature, history, and science in a high school in Paris.

He also traveled the world as a visiting professor. He gave talks about his ideas on the French New Novel. In 1977, he stopped teaching full-time to have more time for his own writing. He still gave occasional talks.

Ricardou earned several advanced degrees in literature. From 1980 until his death in 2016, he also worked part-time as an advisor for a cultural center in France.

He started writing stories in primary school. His professional writing career began in 1955. He decided to write in the style of the "New Novel," which was just starting to become popular.

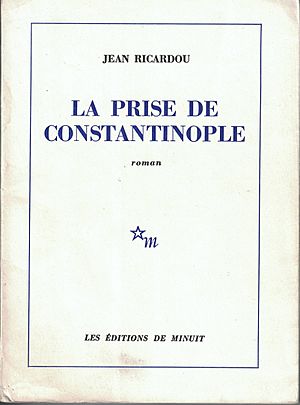

His first novel, L'Observatoire de Cannes, came out in 1961. In 1966, his second novel, La Prise de Constantinople (published in 1965), won the Feneon prize for literature. This was a big award!

Ricardou published his first book about literary theory, Problèmes du Nouveau Roman (1967). He helped organize the first big conference about the French New Novel. Important New Novel writers attended this event. He also led discussions about famous authors like Claude Simon and Alain Robbe-Grillet.

In 1985, while teaching in Paris, he came up with his new theory of writing called "textics." From 1989 to 2015, he held yearly workshops on this topic.

His writing style was very detailed and often poetic. He wanted to connect three different activities: writing stories (fiction), thinking about how writing works (theory), and teaching. He believed these three parts should work together.

Ricardou's Fiction

People often focus on Ricardou's ideas about writing. But he always said that he developed his theories to understand his own stories. He wanted to figure out how his fiction came to be, even parts he didn't plan consciously.

He experimented with writing by using specific rules and methods. He found that these rules, instead of limiting him, actually helped him be more creative. They pushed him to write things he might not have thought of otherwise.

His early writings, including poems, are kept in an archive in France. Some of these early, surrealist-style writings were published in a magazine in 1956.

La Prise de Constantinople

His first novel, L'Observatoire de Cannes, was well-received. This encouraged Ricardou to write a more complex second novel, La Prise de Constantinople. It won the Fénéon prize in 1966.

This book was very new, even for the New Novel movement. For example, the title on the front cover was different from the one on the back! This started a lot of wordplay throughout the book. The pages and chapters were not numbered.

The book also started with the word "rien," which means "nothing." It was like the author Gustave Flaubert's idea of "writing a book about nothing."

La Prise de Constantinople was called a "superbook." It used puzzles and word games from its cover design to create its story. It also explored how the book itself changed as it was written. This novel led to a new way of writing called polydiegetic. This means a story that combines different "stories" that seem to happen in impossible places or times.

Ricardou had a special painting, made around 1960, that hung above his writing desk. It showed his writing process: repeating things but always with a small change.

Les Lieux-dits & Révolutions minuscules

While working on his novels, Jean Ricardou also published shorter stories and essays. These appeared in different literary magazines. In 1962, he joined the team at Tel Quel magazine.

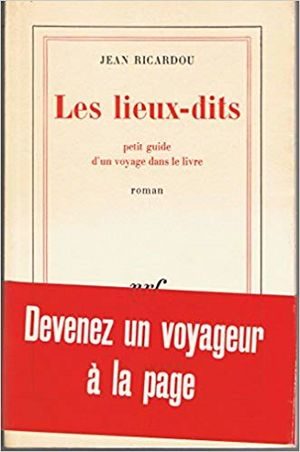

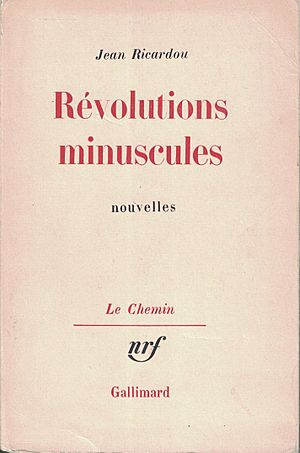

In 1971, he collected many of these stories into a book called Révolutions minuscules. All these stories were written using the special methods of the New Novel. Two years before that, his well-known novel, Les lieux-dits, petit guide d’un voyage dans le livre, was published.

Le Théâtre des métamorphoses

Ricardou's ninth book, Le Théâtre des Métamorphoses, came out in 1982. It was different from his previous books. He called it a "mix."

A "mix" meant it was a work of fiction and a work of theory at the same time. It included poems, illustrations, and different writing styles, all woven together. It wasn't just a simple collection of different things. It was a carefully crafted blend of various parts.

Ricardou wanted to keep readers awake and thinking. He did this by constantly changing the direction of the story. His goal was always to teach the reader something new about texts.

It might seem strange to combine fiction and theory in one book. These two types of writing are usually kept separate. People often think they don't go together.

However, this combination made sense to Ricardou. He wanted to challenge the idea that art and theory must be separate. It also fit his usual way of working: he often switched between writing fiction and writing theory. He also liked to do things in groups of four or eight.

This "mix" book was a very new idea and pushed the boundaries of writing. After this book, it seemed hard to go back to simply alternating between fiction and theory.

In 1988, two more collections of stories followed: La Cathédrale de Sens and a new edition of Révolutions minuscules. These books also included new stories that continued the "mix" idea. For example, La Cathédrale de Sens started with a long, unpublished story. The new Révolutions minuscules included a very complex story that opened with a detailed prose-poem about the game of bocce.

Ricardou's Theories

Jean Ricardou was a key figure in explaining the New Novel literary movement. He wrote several important books about theory: Problèmes du Nouveau roman (1967), Pour une théorie du Nouveau roman (1971), Le Nouveau roman (1973), and Nouveaux Problèmes du roman (1978).

He also wrote his own New Novels, like L’Observatoire de Cannes (1961) and La Prise de Constantinople (1965). Besides his own writing, he organized and published discussions about the New Novel. The famous 1971 conference at Cerisy is very important for understanding French literature of that time.

Before he died in 2016, he was working on a book of interviews. In it, he explained the New Novel movement in a clear and detailed way.

Ricardou's first theory book, Problèmes du Nouveau Roman (1967), shows his way of thinking. He would find a "problem" in a text that no one else noticed. Then, he would find the solution within the text itself.

In this book, he didn't focus on the author's life or hidden meanings. Instead, he looked at how descriptions, metaphors, and the act of writing itself worked in the New Novel. He famously said that the New Novel was "no longer the story of an adventure, but the adventure of a story." This means the way the story is told is more important than what happens in it.

His essays in Problèmes helped people understand New Novels by authors like Michel Butor and Alain Robbe-Grillet. He also looked at classic works like Œdipus Rex and stories by Edgar Allan Poe. By carefully examining the texts, he showed how fiction and narration are connected. He argued that fiction is not just created by narration, but can also challenge itself.

In his second theory book, Pour une Théorie du Nouveau Roman, Ricardou continued to develop his ideas. He applied them to classic authors like Flaubert and Proust. He created new theoretical ideas that he would continue to explore throughout his life.

His third theory book, Le Nouveau Roman, became a classic textbook. A new edition in 1990 included parts of interviews with New Novel writers. It also had a new essay that explained how the movement started and grew.

Complete Works (in French): Published After His Death

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 1: L'Observatoire de Cannes et autres écrits (1956-1961)

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 2: La prise de Constantinople et autres écrits (1962-1966)

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 3: Problèmes du Nouveau Roman et autres écrits (1967-1968)

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 4: Les lieux-dits et autres écrits (1969-1970)

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 5: Révolutions minuscules et Pour une théorie du NR et autres écrits (1971)

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 6: Le Nouveau Roman et autres écrits (1972-1973)

- Intégrale Jean Ricardou tome 7: La révolution textuelle et autres écrits (1974-1977)

Works of Fiction (Novels and Short Stories)

- Novel: L'Observatoire de Cannes (Minuit, 1961)

- Novel: La prise de Constantinople (Minuit, 1965)

- Novel: Les lieux-dits, petit guide d'un voyage dans le livre (Gallimard, 1969)

- Short Stories: Révolutions minuscules (Gallimard, 1971; rewritten and expanded in 1988)

- Short Stories: La cathédrale de Sens (Les Impressions nouvelles, 1988)

Fiction (in English)

- “Epitaphe”, translated by Erica Freiberg, Chicago Review, 1975.

- Les lieux-dits (Place Names: A Brief Guide to Travels in the Book), translated by Jordan Stump for Dalkey Archive Press, is the only book by Ricardou translated into English so far.

Critical Theory (Books)

- Problèmes du Nouveau Roman (Seuil, 1967)

- Pour une théorie du Nouveau Roman (Seuil, 1971)

- Le Nouveau Roman (Seuil, 1973; expanded in 1990)

- Nouveaux problèmes du Roman (Seuil, 1978)

- Une maladie chronique (Les Impressions nouvelles, 1989)

- Un aventurier de l'écriture, interviews with Amir Biglari (Éditions academia be, 2018)

Critical Theory (in English)

- “Rethinking Literature Today”, translated by Carol Rigolot, SubStance, 1972.

- “Composition Discomposed”, translated by Erica Freiberg, Critical Inquiry, 1976.

- “Gold in the Bug”, translated by Frank Towne, Poe Studies, 1976.

- “The Singular Character of the Water”, translated by Frank Towne, Poe Studies, 1976.

- “Birth of a Fiction”, translated by Erica Freiberg, Critical Inquiry, 1977.

- “The Populations of Mirrors: Problems of Similarity on a Text by Alain Robbe-Grillet”, translated by Phoebe Cohen, The MIT Press, 1977.

- “Time of Narration, Time of Fiction”, translated by Joseph Kestner, James Joyce Quarterly, 1978.

- “The Story within the Story”, translated by Joseph Kestner, James Joyce Quarterly, 1981.

- “Nouveau roman, Tel quel”, translated by Erica Freiberg, in Surfiction: Fiction Now … and Tomorrow, 1981.

- “Writing between the Lines”, Ibid., 1981.

- “Proust: A Retrospective Reading”, translated by Erica Freiberg, Critical Inquiry, 1982.

- “Elocutory Disappearance”, translated by Alec Gordon, Atlas Anthology 4, 1987.

- “Immersing the Narrative Text in the Text”, translated by Alan Varley, Jacqueline Berben, Graham Dallas, Style, 1992.

- “Text Generation”, translated by Erica Freiberg, Narrative Dynamics, Essays on Time, Plot, Closure, and Frames, 2002.

Mix (of Theory, Fiction, Poetry, etc.)

- Le Théâtre des métamorphoses (Seuil, 1982)

- Appreciation, first section of Le Théâtre des métamorphoses, translated by Jerry Mirskin and Michel Sirvent, Studies in 20th-century Literature, 1991.

Textics

- Intelligibilité structurale du trait (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2012)

- Grivèlerie (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2012)

- Intellection textique partagée (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2017)

- Intellection textique de l'écrit (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2017)

- Intellection textique de l'écriture (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2017)

- Intelligibilité structurale de la page (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2018)

- Salut aux quatre coins - Mallarmé à la loupe (Les Impressions nouvelles, 2019)

About Textics (in English)

- Interview (with Michel Sirvent): “How to Reduce Fallacious Representative Innocence, Word by Word”, Studies in 20th-century Literature, 1991.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |