John Treloar (museum administrator) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Treloar

|

|

|---|---|

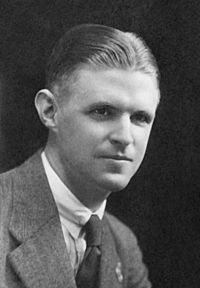

John Treloar in 1922

|

|

| Born | 10 December 1894 Melbourne, Australia

|

| Died | 28 January 1952 (aged 57) Canberra, Australia

|

| Resting place | Woden Cemetery, Canberra |

| Education | Albert Park State School |

| Occupation | Archivist and museum administrator |

| Known for | Director of the Australian War Memorial (1920–1952) |

| Awards | Officer of the Order of the British Empire Mentioned in Despatches |

John Linton Treloar (born 10 December 1894, died 28 January 1952) was an important Australian who helped create and lead the Australian War Memorial (AWM). During World War I, he worked in the army and led a team that collected war records. From 1920, he was the director and played a big part in building the AWM. In World War II, he led a government department and later managed the army's history section. He came back to the AWM in 1946 and stayed its director until he passed away.

Treloar spent his career focused on Australia's military history. Before World War I, he worked for the Department of Defence. After joining the army in 1914, he worked for a top officer, Brudenell White. In 1917, he took charge of the Australian War Records Section (AWRS). In this role, he improved how the army kept records. He also collected many items for future display in Australia.

Treloar became the director of what became the AWM in 1920. He was key in setting up the Memorial and raising money for its building in Canberra. He left the AWM at the start of World War II. He led the Australian Government's Department of Information. Later, he commanded the Australian military's history section. He worked very hard in all his jobs. This sometimes made him unwell. After the war, he returned to the Memorial in 1946. He continued as director until his death in 1952.

Today, Treloar is still seen as a very important person in Australian military history. His main achievements were collecting and organizing Australia's war records. He also successfully established the Australian War Memorial. A street and a storage building near the Memorial are named after him.

Contents

Early Life and Interests

John Treloar was born in Port Melbourne, Victoria, on 10 December 1894. His father sold beer, and his mother was a strict Methodist. John went to Albert Park State School. He also became a trained Sunday school teacher. He could not go to university. Instead, he taught himself by visiting museums and libraries in Melbourne.

Treloar was part of his school's army cadet unit. He believed the military could offer him a good career. He was also a talented athlete. He played football and cricket well. He was even asked to train with a professional football team. But he took his father's advice to wait until he was 21. In 1911, he started working for the Department of Defence. There, he worked as a clerk for Brudenell White. White later became a top Australian army officer.

World War I Service

On 16 August 1914, soon after World War I began, Treloar joined the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF). He became a staff sergeant working for Brudenell White. He landed at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915. He then took part in the Gallipoli Campaign. His main jobs were clerical, like typing reports and orders. He often worked from 7 am until midnight. This hard work affected his health.

He got typhoid fever in August. He was sent to Egypt on 4 September. Treloar nearly died from the illness. He was sent back to Australia to get better. He arrived in Melbourne on 4 December 1915. While recovering, he got engaged to Clarissa Aldridge. His older brother, William, also joined the AIF. William was captured by Turkish forces but survived.

When he recovered, Treloar returned to the military. He tried to rejoin White's staff but could not. Instead, he joined the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) as a lieutenant. In February 1916, he became an equipment officer in Egypt. In July 1916, he moved to France. There, he became White's confidential clerk. He was in charge of the corps headquarters' Central Registry. This office handled communications and orders.

Treloar learned a lot about military record-keeping in these roles. In May 1917, White chose him to lead the new Australian War Records Section (AWRS). He was promoted to captain. At first, he knew nothing about the Section's role.

Collecting War Records

Treloar took command of the AWRS on 16 May 1917. The Section had four soldiers and two rooms in London. It was set up to gather records for official histories after the war. Australia did not have a national archive then. The AWRS was the first group to save government records.

Treloar's first goal was to improve war diaries. These diaries were kept by army units. They were meant to record activities for historians. But most units did not record much detail. Treloar met with officers in charge of the diaries. He gave them advice and feedback. He also showed them that the diaries were important. He explained they would help their units get recognition after the war.

In August 1917, the AWRS started collecting items from battlefields. In September, they also began supervising official war artists. They also kept records of non-official publications. Soldiers were encouraged to give items and records. The AWRS gave out labels to help record details. The AWRS opened offices in France and Egypt. By November 1918, it had about 600 staff.

As commander, Treloar worked with great energy. He sometimes had to be told to take holidays. He told Charles Bean, the official war correspondent, he wanted "to do something really worthwhile for Australia." He actively collected records and items. Bean was impressed but worried Treloar was working too hard. Treloar was awarded the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in June 1918. He was promoted to major in December 1918. This helped his standing at meetings.

Treloar arranged for Clarissa Aldridge to come to Britain in 1918. They married in London on 5 November. They later had four children.

After the War

After the war, Treloar continued to organize the records. Many soldiers helped with this task. The AWRS kept collecting items. By February 1919, they had over 25,000 items. Treloar wanted to collect everything about Australia's war experience. He did not judge the historical value of items. He believed that was for others to do. On 3 June 1919, he was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). He returned to Australia on 18 July 1919.

The many items and records were also sent to Australia in 1919. Organizing them took until 1932. The Australian War Museum was formed in 1919. It was based on the AWRS collection. Treloar joined the Museum that year. Henry Gullett became the first director in August 1919. Bean turned down the job to focus on writing the official history. Treloar became the Museum's deputy director. Bean, Gullett, and Treloar were key to setting up the AWM.

Building the War Memorial

Treloar became the acting director of the Australian War Museum in 1920. Gullett had resigned to lead the Immigration Bureau. Treloar was only 26 years old. He faced the tough job of establishing the institution. Between 1920 and 1922, he did much of the work himself. He developed the Museum's first big exhibition. It opened in Melbourne on Anzac Day 1922.

During this time, the Museum staff also helped distribute captured German equipment. This was given out as war trophies to Australian states. Treloar was on the committee for this effort. The extra work almost overwhelmed him.

Treloar kept adding to the Museum's collections in the 1920s. In 1921, he wrote to all Australian Victoria Cross winners. He asked them or their families to donate diaries or personal items. The Museum also sought diaries and letters from other soldiers. Treloar hoped these records would help study the soldiers.

He also oversaw the creation of several dioramas. These showed important Australian battles. Professional artists made the models. Many of these dioramas are still popular exhibits at the AWM today. Treloar also oversaw the completion of artworks. These had been ordered from official war artists during World War I. The institution was renamed the "Australian War Memorial Museum" in 1923. This was likely Treloar's idea.

Finding a Permanent Home

In its early years, the AWM struggled financially. Treloar raised money and pushed for a permanent building. He and Bean convinced the Museum's committee to raise funds. This way, the Museum would not rely only on government money. In 1921, Treloar set up a sales section. They sold books, art prints, photos, and leftover items. These included German helmets and rifle cartridges.

The government was slow to build a permanent home. Treloar even thought about quitting in July 1922. He considered a job in the Department of Immigration. But he decided to stay. In mid-1923, he went to London. He worked as secretary for Australia's part in the British Empire Exhibition. He returned to Australia in early 1925.

While Treloar was away, the Museum moved to Sydney. Its collection was housed there from April 1925. The institution's name was shortened to "Australian War Memorial" that year. In September, a new law formally established it. This law made it the national memorial to Australians killed in World War I. A board of twelve people oversaw the Memorial. Treloar reported to this board. But they usually let him run the Memorial as he saw fit.

Building a permanent home for the Memorial was delayed by the Great Depression. In January 1924, the government approved building the War Memorial in Canberra. An architecture competition was held. Treloar helped choose the final designs. Work finally began in 1933. The building was finished in 1941. Until 1935, Treloar and his staff were in Melbourne. The collection was split between Sydney and Melbourne. In 1935, Treloar and 24 staff moved to the unfinished building in Canberra. The Sydney Memorial closed, and the collection moved.

Treloar continued to find ways to raise money. He sold guidebooks and art prints. The Memorial also earned a lot of money from Will Longstaff's painting, Menin Gate at Midnight. People paid to see it when it was displayed in 1929. It was so popular that Treloar hired ex-servicemen to sell prints door-to-door.

In 1931, Treloar made sure the Memorial took over publishing the official war history. The books were not selling well. Treloar actively promoted the series. He sold them to RSL branches and public servants. He even set up a plan for public servants to buy books through pay deductions. This was very successful. These efforts greatly increased sales. One historian said Treloar was better at selling books than the original publisher.

Treloar usually worked six days a week, often late into the night. He did not work on Sundays, following his beliefs. He kept adding to the Memorial's collections. He encouraged people to donate letters and diaries. He also focused on keeping the collection safe. In 1933, he personally investigated the theft of a German ship's bell. With his help, the bell was found later that year.

In May 1937, Treloar received a medal for King George VI's coronation. Despite his hard work, Treloar became frustrated. The Memorial's opening was delayed many times. He started looking for a new job in late 1938.

World War II and War Records

Before World War II began, Treloar suggested how the Memorial should respond. He thought it should focus on all wars, not just World War I. He also suggested using the building for storage or government offices. And that its staff should create a new war records section. The AWM board rejected these ideas in October 1939. However, they did offer to help the Department of Defence collect records. So, work continued on the Memorial during the war. In February 1941, the board decided to include the new war in its scope.

Treloar left the Memorial during World War II. In September 1939, his friend Henry Gullett appointed him secretary of the Department of Information (DOI). The DOI was responsible for censorship and spreading government information. Treloar ran the department carefully. He tried to keep its work from becoming political. He wanted to collect historical images, not just publicity photos.

In 1940 or 1941, Treloar asked to lead the War Records Section. This section was part of the army's headquarters. The government agreed in February 1941. Treloar's job was to collect material for the AWM. He also supervised official war artists and photographers. These duties were similar to his work in World War I. Treloar was made a lieutenant colonel. He mainly worked for the AWM, which paid his salary. The army commander, General Thomas Blamey, renamed the section the Military History and Information Section (MHIS). This name better described its role. Unlike the DOI, the MHIS focused on collecting records for historians.

Treloar was sent to the Middle East. Australian forces were fighting there. He also visited Malaya on the way. Conditions in North Africa were harder than in World War I. The fighting moved fast. Soldiers were less motivated to collect items. Treloar had a small staff. But he had disagreements with his second-in-command. He also had less influence with the army. Because he was away, Treloar had little say in the Memorial's design. He could not attend its official opening in November 1941.

After the Pacific War began in December 1941, most Australian forces returned home. Treloar stayed in Egypt until May 1942. He needed to secure space on ships for the Section's large collections. He reached Australia in mid-1942. He was based in Melbourne for the rest of the war. The front line of the Pacific War was just north of Australia. Treloar argued that Australia had a chance to create a complete record of the fighting. Blamey agreed. In July 1942, the MHIS was renamed the Military History Section (MHS). This showed its focus on history. In June 1942, Treloar received a Mention in Despatches for his service.

The MHS continued to produce high-quality records and photos. It also collected these documents and images. By the end of 1944, it had nine field teams. Treloar also focused on the official war artist program. He helped create a high-quality collection of art. However, he did not focus much on collecting physical items. He did not visit New Guinea, which was a main battlefield. This worried Bean.

In August 1943, Treloar's son, Ian, was reported missing. He was serving in the Royal Australian Air Force. It was later confirmed he was killed in action. Treloar's other son, Alan, also served in the army. He won a scholarship after the war.

By early 1944, Treloar was overworked and unhappy. He was also uncomfortable with how Bean and the AWM's acting director, Arthur Bazley, were running the Memorial. He tried to get involved in its management. This frustrated Bazley. It led to growing conflict between them. Their relationship worsened in 1945. The Memorial's board had to step in. In 1946, Bazley left the Memorial due to ongoing tensions with Treloar.

Throughout much of the war, Treloar compiled and edited service annual books. These were collections of articles written by military personnel. He first suggested this in 1941. The first book, Active Service, sold over 138,000 copies. Seventeen such books were produced during and after the war. They sold nearly 2 million copies combined. These books made a lot of money for the Memorial. Treloar's editing work was in addition to his full-time duties. It was a main cause of his exhaustion in the final war years.

Later Years and Legacy

Treloar returned to the AWM on 2 September 1946. He was formally discharged from the Army in 1947. He felt unwell but wanted to work at the Memorial. His daughter, Dawn, moved to Canberra and worked in the Memorial's library. Treloar continued to work long hours. He lived in a small room next to his office. Bean later said Treloar managed almost every part of the Memorial himself. Family and staff felt Treloar was lonely. But he was friendly with the official artists. He became friends with Leslie Bowles and William Dargie.

The main challenges for the Memorial after the war were combining the World War II collections with World War I items. They also needed more funding to expand the building. Treloar did not try to get many new World War II items. As a result, the Memorial's World War II collection was not as strong. Many famous items, like the bomber G for George, were donated by the government. It was not until October 1948 that the government agreed to fund an expansion. This happened after Treloar and the board lobbied for it.

Treloar had trouble managing the Memorial and its staff after World War II. The AWM could find staff, but struggled to keep them. This was due to housing shortages and Treloar's working style. He was friendly and cared about his staff. But he did not give out tasks to others. It was hard for staff to meet him to discuss their work. This caused delays in important projects. One staff member wrote that Treloar was "most dedicated, most incredibly hard-working, most unfailingly kind and most ineffectual." Treloar became very focused on small details. He also gained a reputation for being unable to make decisions.

Treloar's work habits affected his health. His performance declined after 1946, possibly from exhaustion. But the Memorial's board did not step in. They let him stay in his position. In January 1952, Dawn found him ill in bed. Treloar was taken to the hospital. He died on 28 January from internal bleeding. His funeral was held two days later. He was buried in the soldiers' section of Woden Cemetery.

Treloar's death caused problems for the AWM. Because he controlled everything so closely, no one knew his plans. It was unclear how to continue key tasks. These included completing the Roll of Honour and managing finances. Also, two-fifths of the staff positions were empty. Jim McGrath became acting director. He was confirmed in the role in May 1952. Bean, who was chairman of the board, set up a committee. This committee would plan for the Memorial's future. Bean also reviewed the World War I collection. He found that many items were hard to locate. He blamed this on the collection moving between cities. He also blamed the changes in leadership when Treloar was away.

Lasting Impact

After his death, Treloar was praised for his hard work. People also praised the high quality of the Memorial. The Memorial's storage and display building in Mitchell was named the Treloar Resource Centre in his honor. A street behind the main Memorial building was named Treloar Crescent in 1956. The AWM also named a research grant the 'John Treloar Grant'.

Treloar is still seen as a very important person in Australian military history. The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History says the AWM would have failed without him. It states his hard work likely shortened his life. It also calls him "Australia's first great museum professional." The World War I records he organized are still used by historians. They are described as "remarkably detailed and accessible." In 1993, his son Alan published his father's World War I diary.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |