Kalākaua coinage facts for kids

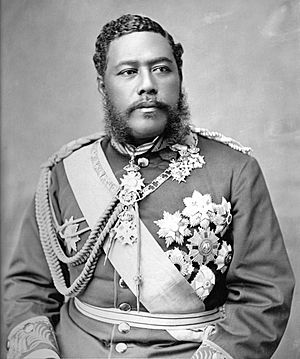

The Kalākaua coinage is a special set of silver coins made for the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1883. King Kalākaua wanted Hawaii to have its own money to show national pride. These coins were designed by Charles E. Barber, who was the main engraver at the United States Mint. They were actually made in the San Francisco Mint in the USA.

The set included four types of coins: a dime (worth ten cents), a quarter dollar, a half dollar, and a dollar.

Even though a law was passed in 1880 to make these coins, nothing happened right away. But King Kalākaua was very interested. Government officials also saw a chance to solve some money problems by issuing coins. A businessman named Claus Spreckels helped arrange everything with the United States. He would make money from the coin production. He agreed with the US Mint to make $1,000,000 worth of coins.

At first, they planned to make a 121⁄2 cent coin. A few test coins were even made. But this idea was dropped so that Hawaiian coins would be similar to US coins. So, a dime was made instead. The coins were minted in San Francisco in 1883 and 1884. However, all the coins have the date 1883 on them.

When the coins arrived in Honolulu, many businesses did not like them. They worried that too much new money would make prices go up. This was a problem because Hawaii was already in a difficult economic time. After some discussions, the government agreed to use more than half of the new coins to support paper money. This continued until the economy improved in 1885. After that, people accepted the coins more easily. They were used in Hawaii until 1903, when Hawaii became a US territory and US money became standard.

Contents

Hawaii's Money History

Before Captain Cook arrived in Hawaii in 1770, Native Hawaiians did not use coins. They traded goods like food and tools directly, which is called barter. When Hawaiians first met explorers, they also traded. Sometimes, things like nails, beads, or small pieces of iron were used as money.

As more trade with other countries began in the early 1800s, coins from many different lands came to Hawaii. These coins were used to pay for Hawaiian goods. Later, missionaries, farms, and other businesses started. This led to the first local money: tokens and scrip. These were like special notes used to pay workers because there wasn't enough small change.

Hawaii had strong trade and cultural ties with the United States. So, businesses in Hawaii started using the US dollar as their main currency. The Hawaiian government would even publish lists showing how much foreign coins were worth compared to the US dollar. This was important because many different coins were used alongside American silver and gold money.

In 1847, King Kamehameha III made a one-cent coin. It was probably made by a company in New England. But merchants did not like it because it was for such small amounts. Only about 12,000 of these coins were ever used. Because this coin was not popular, the government decided not to make more types of coins for a while.

By 1883, most of the money in Hawaii was American. This was because Hawaii and the US had very close economic ties. Hawaiian laws also showed this. American gold coins were considered "legal tender" for any amount. This meant they had to be accepted for payments. American silver coins were legal tender up to $50. In 1879, Hawaii also started issuing its own paper money. These were like certificates that could be exchanged for silver coins. They came in values from $10 to $500.

At that time, gold coins in Hawaii were worth more than their face value if you bought them with silver. This was because gold was needed for certain payments, like customs duties. A lot of silver had been brought into Hawaii in the 1870s. This happened even though the government tried to slow it down with taxes. So, gold was more expensive in Hawaii than in the United States. If a lot of new silver coins, like the Kalākaua coins, were put into circulation, the silver people had might become worth less compared to gold. In 1883, Hawaii was also in a difficult economic period. This was partly because sugar prices had fallen due to too much sugar being produced.

Making the Coins

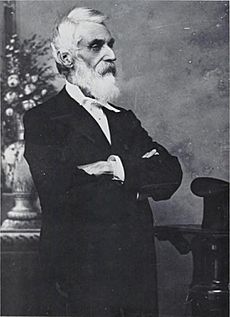

Walter M. Gibson, who was in charge of finances, pushed for a new money law in 1880. He was supported by Samuel G. Wilder, the Minister of the Interior. This law allowed the kingdom to buy gold and silver to make new Hawaiian coins. The government hoped that having its own coins would make Native Hawaiians feel more proud. Their population and influence had been decreasing for decades.

King Kalākaua became more interested in having coins with his picture on them during his world tour in 1881. During this trip, he met someone who owned a nickel mining company. This person wanted to use nickel for coins. Sample five-cent coins were sent to the king after he returned to Honolulu. But these coins were not liked, possibly because Hawaii's motto was spelled wrong.

Nothing happened until 1882, when the king chose Gibson to lead the government. Gibson then moved forward with the coin idea. The coins were to have the king's image on the front side. On the back, they would have Hawaii's coat of arms and motto. The motto is "Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono" (The Life of the Land is Perpetuated in Righteousness). The 1880 law said that the silver coins should be in denominations of one dollar, fifty cents, twenty-five cents, and twelve and one-half cents. A twelve and one-half cent coin, also called "one bit," was sometimes a laborer's daily pay.

A law called the National Loan Act allowed for $2 million in government bonds. But Hawaii's government had trouble selling these bonds because its financial standing was not good. Gibson came up with an idea to combine the two laws. He suggested that businessman Claus Spreckels, a close friend of the king, be appointed as a government agent. Spreckels would arrange for the coins to be made at the United States Mint. In return, Spreckels would be paid with government bonds.

In March 1883, the cabinet council allowed Finance Minister John Mākini Kapena to make this deal with Spreckels. Spreckels officially got this role in May. H.A.P. Carter, Hawaii's representative in Washington, helped connect the Hawaiians and the US government. He wrote to Kapena in June that US officials thought this arrangement was unusual. Usually, the Hawaiian government would just contract directly and pay cash for the coins.

Spreckels was already talking with American officials. In January 1883, Horatio Burchard, the Director of the United States Mint, wrote to him. He explained the laws for making coins for foreign governments. He said the coins could be made at the San Francisco Mint. But the designs for the coins would have to be prepared in Philadelphia. He asked Spreckels for sketches. Spreckels sent a sketch showing a full-face picture of the king. But Charles E. Barber, the Chief Engraver in Philadelphia, said it was too hard to use. Barber suggested showing the king's profile instead. A good photograph was sent to him to help create models for the coins.

Once the Mint received Spreckels' official role as agent, the Acting Director, Robert E. Preston, wrote back. He noted that the authorization asked for 121⁄2 cent pieces. But Hawaiian law said the coins should be the same size, weight, and purity as US coins. And the US Mint did not make a 121⁄2 cent coin. He asked if they wanted ten-cent pieces instead. No answer came right away. So, Barber finished the first designs, including the 121⁄2 cent piece.

Barber finished the main models, called hubs, for the four coins in September 1883. The Philadelphia Mint Superintendent, A. Loudon Snowden, had two sets of coins made and sent them to Preston in Washington. Snowden praised how beautiful the coins were. He was also happy that Barber used less relief (how much the design sticks out) than on US coins. This meant the coins would be easier to make. Preston sent the coins to Spreckels in San Francisco. He also allowed Philadelphia to make more sets. These were for the Mint's own collection and for the director's office in Washington. Barber was told to make five sets of coining dies (the tools that stamp the coins) for each coin type. These were to be sent to the San Francisco Mint. But no coins were to be made until a final contract with Spreckels was signed. The dies would remain Hawaii's property and be returned if asked for.

The official contract was signed on October 29 by Spreckels, acting for Hawaii, and E. F. Burton, the San Francisco Mint Superintendent. It said that $1,000,000 worth of coins would be made. This included $500,000 in silver dollars, $300,000 in half dollars, $125,000 in quarter dollars, and $75,000 in dimes. The Hawaiian government changed from 121⁄2 cent pieces to dimes. This was because they were trying to make a money agreement with the United States. They wanted their coins to match America's, though this agreement never happened.

By mid-November, the Mint noticed the change. Spreckels sent a confirmation and permission to make dies for the dime. It was understood that a new official approval from Honolulu would be needed before dimes could be produced. This approval arrived in December. By this time, the kingdom's order was already being made, starting with half dollars in November. Barber did not finish the dime hubs until January 1884. The dies were not sent to San Francisco until February, even though they all have the date 1883. Once he received the dies for the ten-cent coin, Burton sent the unneeded 121⁄2 cent dies to the director's office in Washington.

Spreckels provided the silver for the coins, which cost about $850,000. He paid $17,500 to the Mint for making the coins, $2,500 for the designs, and $250 for the dies. A final change reduced the total value of dimes to $25,000 (250,000 coins). The value of half dollars was increased to $350,000 (700,000 coins).

Coin Designs

Charles E. Barber designed both sides of each coin. The front side, called the obverse, shows a picture of King Kalākaua. His name and title are around him, and the date is below. W. T. R. Marvin, who wrote about coins in 1883, said that people who saw the coins thought the king's profile looked as good as those of rulers from more important countries. Ernest Andrade, who wrote about the coin controversy, said they showed Kalākaua's profile, which he called "handsome."

The dollar, half dollar, and quarter dollar coins show the royal coat of arms on the back side, called the reverse. On the dollar coin, the shield is shown on a special cloak, possibly made of ermine fur. Marvin suggested that the famous feather cloak worn by Kamehameha the Great would have been a better choice than fur. Below the shield on the dollar is the Star of the Order of Kamehameha, a royal award. Above it is the royal crown.

Around the coin is Hawaii's motto, "Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono". These words were spoken by Kamehameha after a difficult time. On either side of the shield are the letters "1" and "D." Below is the value of one dollar written in Hawaiian, "AKAHI DALA". "Dala" became the Hawaiian word for dollar during missionary times. This happened as words changed to fit the smaller Hawaiian alphabet. The word "dollar" is pronounced "dala" in many parts of Asia and the Pacific.

The back sides of the half dollar and quarter dollar coins show the coat of arms without the cloak or the royal order. The motto surrounds them. The value is shown as "HAPALUA" for half dollar and "HAPAHA" for quarter dollar. Each of these two coins has its fraction with the letter "D." on either side of the shield.

The 121⁄2 cent coin, which only exists as a few special proof pieces today, has a wreath with a crown separating its branches. The motto surrounds it. The value is inside the wreath, written as "HAPAWALA". This design was then used for the dime. On the dime, the value inside the wreath is "UMI KENETA". Below the wreath, it says "ONE DIME". Both phrases mean ten cents.

What Happened to the Coins?

Some of the coins that were not exchanged for new money were likely lost in fires. These fires destroyed Honolulu's Chinatown in 1887 and 1900. People in that community often did not trust banks. They would hide valuable items in their homes. Many remaining coins were used by jewelers. They bought thousands of dollars worth of coins in the last months they were legal money.

After Hawaii became a US territory in 1900, many people wanted souvenirs of the old kingdom. A wide variety of items were sold featuring the coins. These included jewelry like pins, watch fobs, cuff links, belt buckles, and hat pins. Decorative items like spoons and napkin rings were also made. Usually, the side of the coin with the coat of arms was decorated with enamel.

Coin collectors today own some of the Kalākaua coins. The 2018 edition of Richard S. Yeoman's A Guide Book of United States Coins says the quarter dollar is usually the least expensive Hawaiian coin. It can cost from $50 to $375 for coins that were used in circulation. Proof coins are much more expensive. For example, a 121⁄2 cent piece (hapawalu) sold for $43,125 at an auction in 2011. The Kalākaua coins have also been copied. Their designs have been used for medals made by private companies. The original tools used to make the coins were officially marked as unusable. They are now kept in the Hawaiʻi State Archives.

How Many Coins Were Made?

The table below shows how many of each type of Kalākaua coin were made.

| Coin Type | For Circulation | Proof (Test Coins) | Melted Down | Total Distributed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dime | 250,000 | 26 | 79 | 249,947 |

| 121⁄2 cents | 0 | 20 | 0 | 20 |

| Quarter dollar | 500,000 | 26 | 257,400 | 243,626 |

| Half dollar | 700,000 | 26 | 612,245 | 87,781 |

| Dollar | 500,000 | 26 | 453,652 | 46,374 |