Law of Æthelberht facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Law of Æthelberht |

|

|---|---|

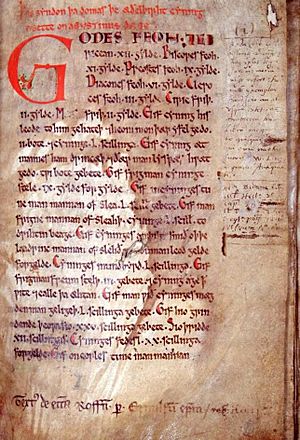

Opening folio of the code

|

|

| Ascribed to | Æthelberht, king of Kent |

| Language | Old English |

| Date | 7th century |

| Principal manuscript(s) | Textus Roffensis |

| First printed edition | George Hickes and Humfrey Wanley, Linguarum Vett. Septentrionalium Thesaurus Grammatico-Criticus et Archaeologicus (Oxford, 1703–05) |

| Genre | law code |

The Law of Æthelberht is a very old set of rules from the early 600s. It was written in Old English, which is an early form of the English language. This law code came from the kingdom of Kent in England. It's special because it's the first known law code written in any Germanic language. It's also believed to be the oldest surviving document written in English! We only have a copy from the 1100s, found in a book called Textus Roffensis.

These laws mainly aimed to keep peace and order in society. They did this by setting clear rules for paying back people who were hurt or wronged. This was common in old Germanic legal systems. The amount of payment depended on a person's social rank, from the king down to a slave. The first parts of the law protected the church. While some parts were new ideas, much of the law likely came from older customs passed down by word of mouth.

Contents

The Only Surviving Copy of the Law

There is only one surviving copy of King Æthelberht's law. It is found in a book called Textus Roffensis, also known as the "Rochester Book". This book is a collection of Anglo-Saxon laws, lists, and family trees. It was put together around the early 1120s. This was about 500 years after Æthelberht's law was first written down.

The laws of Æthelberht are found at the very beginning of the Textus Roffensis. They come before other laws from Kent and other parts of England. The same person wrote down Æthelberht's law as well as the laws of other Kentish kings.

The Textus Roffensis was created because Ernulf, who was the bishop of Rochester, asked for it. Bishop Ernulf was very interested in law, much like his friend, the lawyer-bishop Ivo of Chartres. Ernulf also asked for copies of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to be made at other important churches.

In 2014, Rochester Cathedral and the John Rylands University Library of Manchester made the full text of Textus Roffensis available online. This means people can now see the old document for themselves.

Where Did the Law Come From?

The Law of Æthelberht is named after King Æthelberht. He ruled from about 590 to 616 or 618 AD. This is why the law is thought to be from his time. It is believed to be the oldest law code in any Germanic language. It's also the earliest document we have written in the English language. The Textus Roffensis says in red ink at the start that King Æthelberht created it.

Bede, a famous writer from the 700s, also wrote about King Æthelberht's laws. He said that the king "established enacted judgments for them, following the examples of the Romans." Bede added that these laws were "written in English speech." He said they were still used in his time. Bede's description of the laws matches what we find in the Textus Roffensis. Even Alfred the Great, a later king, said he looked at Æthelberht's laws when making his own.

The original law text itself does not say it was written by the king. The person who added the red-ink note in the 1100s might have been influenced by Bede's writings. The fact that the original text doesn't name the king might show that making laws wasn't just a king's job back then.

Old Customs and New Ideas

Much of the law likely came from old customs that were passed down orally, meaning by speaking, not writing. The law's structure seems like a way to help people remember it. It starts with the most important person, the king, and ends with slaves. The section about injuries also follows a pattern. It starts with injuries to the head and goes down to the toenail.

The use of poetic styles, like repeating sounds (alliteration), also suggests the law was once spoken. This means Æthelberht's law mostly came from ælþeaw, which means "established custom." It was less about the king's new domas, or "judgements."

It's not fully clear why the law was written down. It happened around the time Christianity came to the English people in Kent. Christianity was the religion of the Romans and the Franks. The law might have been an attempt to be more like the "civilized" Romans. Christianity and writing were also helped by King Æthelberht's marriage to Bertha. She was the daughter of the Frankish king Charibert I.

Some historians think Augustine of Canterbury, a missionary, might have encouraged the writing of the law. One historian, Patrick Wormald, suggested it followed a plan from a church meeting in Paris in 614. The abbot of St Augustine's and the bishop of Rochester attended this meeting. The payments for churchmen in Æthelberht's law are similar to those in other old Germanic laws.

What the Law Says

The Law of Æthelberht covers many different situations. It sets out how much compensation, or payment, should be made for various wrongs. Legal experts have divided the text into sections based on who is involved.

Here are some of the main sections:

- Payments for Church People: Rules for how much to pay if someone harms a church official or church property.

- Payments for the King and His Household: Rules for offenses against the king or people who work for him.

- Payments for Noblemen (eorlas): Rules for wrongs committed against important noble people.

- Payments for Freemen (ceorlas): Rules for offenses against regular free people.

- Payments for Semi-Free People: Rules for people who were not fully free, but not slaves either.

- Personal Injuries: This is a large section covering payments for different types of injuries, from a cut finger to a lost eye.

- Payments and Injuries for Women: Rules about wrongs committed against women.

- Payments for Servants: Rules for offenses against people who worked as servants.

- Payments for Slaves: Rules for wrongs committed against slaves.

The law helped to prevent fights and end disputes by setting clear ways to "right wrongs." The law used two types of money: the scilling (shilling) and the sceatt. In Æthelberht's time, a sceatt was a small amount of gold, about the weight of a barley grain. There were 20 sceattas in one scilling. One ox was probably worth one scilling.

The Language of the Law

The law is written in Old English, and it uses many old language features. For example, it uses a special way of saying "with 4 shillings" that was not common in later Old English. This way of speaking is found in other old Germanic languages.

Some words in the law are very rare or not found in other Old English texts. Examples include mæthlfrith ("assembly peace") and feaxfang ("seizing of hair"). The meaning of some words is still debated by experts. For instance, the word læt might have meant a freed person. Some thought it meant people from the native British population of Kent. However, newer studies suggest it just meant a certain social status, not an ethnic group.

The law also sometimes doubles vowels to show a long sound, like taan for "foot." This was common in early medieval writing in England but became less common later.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |