Anglo-Saxon law facts for kids

Anglo-Saxon law was a set of written rules and traditions used in England during the Anglo-Saxon period, before the Norman conquest in 1066. These laws were similar to other early laws from places like Scandinavia and Germany, all coming from ancient Germanic customs. However, Anglo-Saxon laws were special because they were written in Old English instead of Latin. They were the second laws in medieval Western Europe, after those from Ireland, to be written in a language other than Latin.

Contents

History of Anglo-Saxon Law

The first people in England were the Celtic Britons. Their laws were not written down but were remembered and taught by Druids, who were also judges. After the Roman conquest of Britain in the first century, Roman law was used, at least for Roman citizens. But when the Romans left in the 5th century, their legal system disappeared.

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Anglo-Saxons came from Germany and set up several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Each kingdom had its own legal traditions based on Germanic law. These traditions were not much influenced by Celtic or Roman laws. After the Anglo-Saxons became Christian, they started writing down their laws, which were called "dooms." Christian priests brought the skills of writing and reading with them.

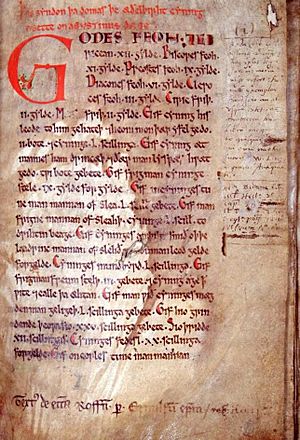

The very first written Anglo-Saxon laws were created around the year 600 by Æthelberht of Kent. A writer named the Venerable Bede said that Æthelberht made his laws "following the examples of the Romans." This probably meant he was inspired by other Roman-influenced groups, like the Franks, who had written down their laws. As a new Christian king, Æthelberht's law code showed he was part of the Roman and Christian traditions. However, the laws themselves were not based on Roman law. Instead, they wrote down older customs and protected the church, as bishops helped write them. The first few rules were all about paying back the church for any damage.

In the 9th century, an area called the Danelaw was taken over by Danes and was governed by Scandinavian law. The word "law" itself comes from the Old Norse word laga. Starting with Alfred the Great (who ruled from 871 to 899), the kings of Wessex united the Anglo-Saxon people against the Danes. Through this, they created a single Kingdom of England. This joining of kingdoms was finished under Æthelstan (who ruled from 924 to 939). The Norman Conquest in 1066 ended the Anglo-Saxon monarchy. But Anglo-Saxon laws and systems continued and became the basis for later English law, known as the common law.

Sources of Law

Anglo-Saxon law came from two main places: folk-right (customary law) and royal laws.

Folk-right: The Unwritten Rules

Most laws in Anglo-Saxon England came from folk-right, which was unwritten custom. These customs were mainly used and decided in local courts, like the shire court and hundred courts. There were no professional judges back then. Instead, the people who had to attend the court made the decisions. Royal officials called reeves made sure that folk-right was followed.

Older laws about land, who inherited property, agreements, and standard fines were mostly based on folk-right. These customs could be different from one local area to another. For example, there were different folk-rights for people in Wessex, Essex, East Anglia, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, the Danelaw, and for Welshmen. These main differences stayed even when the smaller kingdoms joined into one larger kingdom.

Kings could change or add to folk-right with special laws or grants. The Church often suggested these changes. For example, a special type of land ownership called bookland was created. Rules about family inheritance could be changed by allowing people to make wills. Special permissions were also given, like being free from the hundred court's power or having special rights to collect fines. Over time, these royal grants became very important and led to a new legal system called the feudal system.

Royal Law Codes: Written Laws from Kings

Besides folk-right, kings could also create new laws to make older ones clearer. These royal law codes were written for specific situations and were meant for people who already knew the law. Anglo-Saxon kings made rules about selling animals with witnesses, chasing thieves, and requiring people to prove they owned what they sold. Groups of people who promised to be responsible for each other also became important. A hlaford (lord) and his hired men were not just a private group, but also helped to catch criminals and suspicious people.

The first written law code was the Law of Æthelberht (around 602 AD). It wrote down the unwritten customs of Kent. After this, two more Kentish law codes followed: the Law of Hlothhere and Eadric (around 673-685 AD) and the Law of Wihtred (695 AD). Outside of Kent, Ine of Wessex issued a law code between 688 and 694 AD. Offa of Mercia (who ruled from 757 to 796 AD) also made a law code, but it no longer exists.

Alfred the Great, king of Wessex, created a law code around 890 AD, known as the Doom Book. The introduction to Alfred's code says that the Bible and church rules were studied to help create it. Older law codes from Æthelberht, Ine, and Offa were also looked at. This might have been the first attempt to create a set of similar laws across England, setting an example for future English kings.

The House of Wessex became rulers of all England in the 10th century, and their laws were used throughout the kingdom. Important law codes in the 10th century were made by Edward the Elder, Æthelstan, Edmund I, Edgar, and Æthelred the Unready. However, local differences in laws and customs still existed. The Domesday Book of 1086 noted that different laws were used in Wessex, Mercia, and the Danelaw.

The law codes of Cnut (who ruled from 1016 to 1035 AD) were the last laws made during the Anglo-Saxon period. They were mostly a collection of earlier laws. After the Norman Conquest, these laws became the main source for understanding old English law. For political reasons, these laws were later said to be from Edward the Confessor (who ruled from 1042 to 1066 AD). Under the name Leges Edwardi Confessoris, they gained great importance and inspired the Magna Carta in 1215. They were also included in the Coronation Oath for centuries. The Leges Edwardi Confessoris is the most famous of the custumals, which were books written after the Conquest to explain Anglo-Saxon customs to the new Norman rulers.

Courts and Justice

The Anglo-Saxons had a well-organized system of meetings or "moots" (from the Old English words mot and gemot, meaning "meeting").

The Witan: King's Court

The witan (or witanagemot) was the king's own court. With advice from his important noblemen (ealdormen), the king made final decisions himself. He heard cases about royal property or serious crimes against the king, as well as appeals from lower courts.

Shire and Hundred Courts

By the 10th century, England was divided into areas called shires. The shire court met twice a year to handle important community matters. It was overseen by the ealdorman (later called an earl) and the bishop. The "shire reeve" or sheriff was an official who first appeared in written records in the 11th century, but the role probably existed earlier. The royal sheriff was one of the most powerful officials in Anglo-Saxon England.

Each shire was divided into smaller units called hundreds. These hundreds had their own courts that met every month. All free men over the age of twelve were expected to attend. The hundred court's officer was the reeve, a royal official chosen by the king. His job included collecting money for the king and handling court business. His power and the ealdorman's power seemed to overlap.

Hundreds were further divided into "tithings." These were groups of ten households, and each tithing had a tithingman responsible for it. Tithings were part of a system called frankpledge, where people helped police themselves. Every man belonged to a tithing and promised to report crimes committed by others in his group. If he didn't, he could be fined. Most daily administrative and court business was handled by the hundred court.

Boroughs (towns) were separate from the hundreds and had their own meetings (called burghmoot, portmanmoot, or husting). These met three times a year. London's Court of Husting had the same authority as a shire court, and the city was divided into wards.

Private Courts

During the Anglo-Saxon period, the king could create private courts in two ways:

- The king could give the church (either a bishop or the abbot of a religious house) the right to manage a hundred. The hundred's reeve would then report to the bishop or abbot. The same types of cases would be heard, but the money from fines would now go to the church.

- The king could grant special rights to a landowner, called sake and soke, through a written order or charter. This gave the landowner the right to hold a court with power over his own lands, including the power to punish thieves caught on his land (called infangthief).

The king could take away these special rights if they were misused.

Key Features of Anglo-Saxon Law

Compensation and Punishment

Early law codes aimed to stop violent arguments between families by requiring criminals to pay money (called bote) to victims or their families for injuries or death. If someone was killed, the victim's family was owed a wergild ("man price"). Anglo-Saxon society had different social levels, and a person's wergild was higher or lower depending on their status:

- King

- Ætheling (prince)

- Ealdorman (a powerful nobleman)

- Thegn (a lesser nobleman)

- Ceorl (a low-ranking free person)

- Slave

Anglo-Saxon England did not have professional police. To catch a criminal, victims or witnesses could raise the "hue and cry." This meant every able-bodied man had to do everything he could to chase and catch the suspect.

Trial Methods

There were two ways to start court cases. In one, the person who claimed to be a victim made an accusation, which the accused person formally denied. The second way was the "presentment" of crimes as part of the frankpledge system (mentioned above). Since there were no juries, cases were decided by the people who had to attend the court: for the hundred court, it was all free men, and for the shire court, it was the thegns.

Cases about land disputes were often decided based on written documents (charters) and what local people knew. For other types of cases, evidence and witnesses were less important. Communities used trial by oath and trial by ordeal to decide if someone was guilty. In trial by oath (also called compurgation), the accused person swore on the Bible that they were innocent without being questioned. The accused also had to bring "oath-helpers," who were neighbors willing to swear that the accused was a good person and could be trusted to tell the truth. In Christian Anglo-Saxon society, lying under oath was a serious sin against God. If the accused swore innocence and brought the right number of oath-helpers (usually 12), they were found not guilty.

If an accused person could not prove their innocence by oath in criminal cases (like murder, theft, or witchcraft), they might still clear their name through trial by ordeal. Trial by ordeal was a way to ask God to show if someone was lying. Because it was seen as divine, the church regulated it. A priest had to oversee the ordeal in a place chosen by the bishop. The most common types in England were ordeal by hot iron and ordeal by water. Before an accused person went through the ordeal, the person making the accusation had to present a clear case under oath. The accuser was helped by their own supporters, who might act as witnesses.

Peace and Protection

Another very important part of Anglo-Saxon law was its focus on keeping the peace. Even in Æthelberht's early laws, there were specific fines for breaking the peace of a household, depending on the rank of the householder—a ceorl (free person), an eorl (noble), or the king himself. This showed that the law recognized the father's authority over his family, a master's over his servants, and a lord's over his followers. The fence around a house was considered sacred, and crimes committed inside it were punished severely. This Anglo-Saxon idea of peace is where the later legal idea of the king's peace comes from.

Protection (called mund in Old English) was given through family ties or by serving a lord (called hlaford, meaning "bread-giver"). People who were not protected by a lord or family (like foreign traders) were under the king's protection.

The law codes from the early 11th century (like those of Cnut and Aethelred) set up specific conditions for guaranteed peace or protection based on certain times or places. This was known as grith. Examples include ciric-grið ("church-grith," which was the right of asylum in a church) or hand-grið ("hand-grith," protection under the king's hand).

Land Law

Many parts of England (including Kent, East Anglia, and Dorset) used forms of partible inheritance. This meant that land was divided equally among heirs. In Kent, this was known as gavelkind.

Slavery

Slavery was common in Anglo-Saxon England. A slave (called þēow in Old English or þræll in Old Norse) might have sold themselves into slavery, become a slave as a punishment (for theft, for example), or been enslaved after being captured in war. While owners had a lot of power over their slaves, their power was not total.

There is evidence that slavery was becoming less common by the late Anglo-Saxon period. One reason was that the church did not approve of it, and Christians were encouraged to free their slaves before they died. Another reason was that turning slaves into serfs (people tied to the land) was more practical for the economy.

Religion and the Church

The creation of written law codes happened at the same time as the spread of Christianity. The Anglo-Saxon church received special rights and protections in the earliest laws. The Law of Æthelberht required payment for crimes against church property:

- 12 times the value for church property

- 11 times the value for a bishop's property

- 9 times the value for a priest's property

- 6 times the value for a deacon's property

- 3 times the value for a cleric's property

In the late 7th century, the laws of Kent and Wessex supported the church in many ways. Not getting baptism was punished with a fine, and the oath of a Christian who had taken communion was worth more than a non-Christian's oath in court. Laws supported observing the Sabbath (Sunday rest) and paying church dues (church-scot). Laws also set up rights to church sanctuary (a safe place where people could not be arrested).

Influences on Anglo-Saxon Law

The oldest Anglo-Saxon law codes, especially from Kent and Wessex, show a strong connection to Germanic law. For example, they divided social ranks in a way similar to how people were ranked in Lower Germany.

Later, there were many similarities between the laws of Charlemagne and his successors in Europe and the laws of Alfred, Edward the Elder, Æthelstan, and Edgar in England. This was less because they copied each other directly, but more because they faced similar political challenges. After the Norman Conquest, Frankish law became a strong influence on English legal history.

The Scandinavian invasions brought many northern legal customs, especially in the area known as the Danelaw. Old records like the Domesday Book show clear differences in local organization and justice in places like Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, and Yorkshire. There were also special customs for fines and keeping the peace. However, the introduction of Danish and Norse elements was more important because of the conflicts and agreements it caused, and its social effects, rather than bringing many completely new ideas into English law. The Scandinavian newcomers blended easily and quickly with the local population.

The direct influence of Roman law was not very strong during the Saxon period. There wasn't a direct transfer of important legal ideas or a continuous flow of Roman traditions in local customs. But Roman law did have an indirect influence through the Church. Even though the Anglo-Saxon Church seemed isolated, it was still filled with Roman ideas and culture. Old English "books" (charters and legal documents) were indirectly based on Roman styles. The tribal law of land ownership was greatly changed by new ideas about individual ownership, gifts, wills, and the rights of women. However, the Norman Conquest further increased Roman ideas by connecting the English Church more closely with France and Italy.

Language of the Laws

The English dialect used in most Anglo-Saxon laws is a common language that came from the West Saxon dialect. Wessex was the main part of the united Kingdom of England, and the royal court at Winchester became the main center for writing. You can find traces of the Kentish dialect in the Textus Roffensis, an old book that contains the earliest Kentish laws. Northumbrian dialect differences are also seen in some law codes. Some Danish words appear as technical terms in certain documents. After the Norman Conquest, Latin replaced English as the language for writing laws, though many technical English terms that Latin didn't have an equivalent for were kept.

See also

In Spanish: Derecho anglosajón para niños

In Spanish: Derecho anglosajón para niños

Comparative customary law systems

- Cyfraith Hywel (Wales)

- Early Irish law

- Leges inter Brettos et Scottos (Scotland)

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |