Medieval cuisine facts for kids

Medieval cuisine is all about the food, eating habits, and cooking styles in Europe during the Middle Ages. This time period lasted from the 5th to the 15th century. During these years, diets and cooking changed slowly.

Grains were the most important food for people. Rice came to Europe late, and potatoes were not used much until the 16th century. Poor people ate barley, oats, and rye. Wheat was more expensive. Everyone ate these grains as bread, porridge, or pasta. Cheese, fruits, and vegetables were important for poorer people. Meat was more costly and usually eaten by richer people. Wild game, like deer, was mostly for nobles who hunted. The most common meats were pork, chicken, and other birds. Beef was less common because it needed a lot of land to raise cows. Many kinds of fish from rivers and the sea were also eaten. Cod and herring were very important in northern areas.

Transporting food over long distances was slow and expensive. This meant that rich people's food was more influenced by foreign styles. They used exotic spices and costly imports. Everyone tried to copy the social class above them. So, new ideas from trade and wars slowly spread to the wealthy middle class in cities. Laws also stopped people from showing off too much with their food. People believed that hard workers should eat simple, cheap food.

A special kind of cooking developed in the Late Middle Ages. It became the standard for nobles across Europe. Rich people's food often tasted sweet and sour. They used ingredients like verjuice (sour grape juice), wine, and vinegar. Spices like black pepper, saffron, and ginger were also popular. Honey or sugar made many dishes sweet and sour. Almonds were very popular for making soups, stews, and sauces thicker. Almond milk was used a lot.

Contents

Eating Rules and Habits

For a long time, people in the Mediterranean area ate mostly grains, especially wheat. Porridge and bread became the main foods, providing most of the calories for many people. From the 8th to the 11th centuries, grains made up a much bigger part of people's diets. Bread was very important in religious ceremonies, like the Eucharist. This made it a highly respected food. Only olive oil and wine were seen as equally valuable. But these were mostly for warmer regions where grapes and olives grew.

The Church's Influence

The Catholic and Orthodox Churches had a big impact on what people ate. Christians were not allowed to eat meat for about one-third of the year. During strict fasting times, all animal products were forbidden. This included eggs, milk, and cheese. Sometimes, even fish was not allowed. People also fasted before taking the Eucharist. These fasts sometimes lasted a whole day and meant no food at all.

The Churches said that feast days should switch with fast days. In most of Europe, Fridays were fast days. Fasting also happened during Lent and Advent. Meat and animal products like milk, cheese, butter, and eggs were not allowed. Sometimes, fish was also forbidden. Fasting was meant to help people control their bodies and strengthen their souls. It also reminded them of Jesus' sacrifice. The goal was not to say certain foods were bad. It was to teach self-control. On very strict fast days, people ate only one meal.

Even though most people followed these rules, they often found ways around them. Writer Bridget Ann Henisch said that people love to make rules, then find clever ways to break them. Lent was a challenge, and people enjoyed finding loopholes.

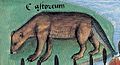

During fasting, animal products were supposed to be avoided. But people often made practical choices. The word "fish" was sometimes used for water animals like whales, puffins, and even beavers. This was because they spent a lot of time in water. Even if food choices were limited, meals were not always small. There were no rules against drinking (in moderation) or eating sweets. Fish-day banquets could be grand. People served "illusion food" that looked like meat, cheese, or eggs. Fish could be shaped to look like deer meat. Fake eggs were made by filling empty eggshells with fish roe and almond milk.

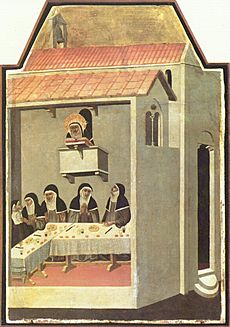

From the 13th century, fasting rules became stricter. Nobles avoided meat on fast days but still ate fancy meals. Fish replaced meat, often shaped like ham or bacon. Almond milk replaced cow's milk as an expensive alternative. Fake eggs made from almond milk were cooked in eggshells. These were flavored and colored with costly spices. Some monasteries, like Benedictine ones, served up to sixteen courses on certain feast days.

Exceptions to fasting were often made for many groups. Thomas Aquinas (around 1225–1274) thought children, the old, travelers, workers, and beggars should be excused. Monks often found ways around the rules. Since sick people were exempt, some monks would eat their fast-day meals in a special room called the misericord, not the main dining hall. Church leaders tried to fix this by making sure good non-meat dishes were available on fast days.

Social Class and Food

Medieval society had strict social classes. Food was a big sign of a person's status. This is very different from today. Society had three main groups: commoners (workers), clergy (church members), and nobility (rich landowners). The nobility and clergy were at the top. People were expected to stay in their social class. They also had to respect those above them. Showing off wealth was a way to show power.

Rich nobles ate fresh game with exotic spices. They used refined table manners. Hard-working laborers ate coarse barley bread, salted pork, and beans. They were not expected to have fancy manners. Even health advice was different for each class. It was thought that a lord's body was more refined. So, it needed finer foods than a common worker's body.

In the late Middle Ages, middle-class merchants became richer. They started to copy the nobles. This worried the nobility. So, two things happened: writers warned people not to eat food that was wrong for their class. Also, laws were made to limit how fancy commoners' banquets could be. Even parts of animals were assigned to different social classes.

Health and Food

Medieval medical science greatly influenced what rich people thought was healthy. A healthy life included diet, exercise, and proper behavior. All foods were thought to have certain properties. They were classified as hot or cold, and moist or dry. This was based on the "four humours" theory by Galen. This theory was popular throughout the Middle Ages.

Scholars believed that digestion was like cooking. Food in the stomach continued the cooking process. To digest food well, the stomach needed to be filled correctly. Easily digestible foods were eaten first, followed by heavier dishes. If not, heavy foods might block digestion. This could cause food to rot and create bad humours. It was also important not to mix foods with different properties.

Before a meal, the stomach was "opened" with an appetizer. This was usually hot and dry. It could be sweets made from honey or sugar-coated spices like ginger or anise. Wine and sweetened milk drinks were also used. After the meal, the stomach was "closed" with a digestive. This was often spiced sugar lumps or spiced wine. Aged cheese was also common.

Ideally, a meal started with light fruits like apples. Then came vegetables like cabbage and lettuce, and light meats like chicken. Pottages and broths were also eaten. After that, "heavy" meats like pork and beef were served. Pears and chestnuts were considered hard to digest. It was popular to finish with aged cheese and digestives.

The best food was thought to be moderately warm and moist. Food should also be finely chopped, ground, or strained. This helped mix all ingredients well. White wine was seen as cooler than red wine. Egg yolks were warm and moist, while whites were cold and moist. Cooks were expected to follow these health rules.

Food Across Europe

Different parts of Europe had their own food traditions. These differences were mainly due to climate, local rules, and customs. In the British Isles, northern France, and Scandinavia, the climate was too cold for grapes and olives. In the south, wine was the common drink for everyone. In the north, beer was the common drink, and wine was an expensive import. Citrus fruits and pomegranates were common around the Mediterranean Sea. Dried figs and dates were available in the north but used sparingly.

Olive oil was used everywhere in Mediterranean cultures. But it was expensive in the north. There, people used oils from poppy, walnut, or hazelnut. Butter and lard were used a lot in northern Europe, especially after the Black Death made them more available. Almonds were used almost everywhere in middle and upper-class cooking. Almond milk was very common and used instead of eggs or milk in many dishes.

Meal Times and Manners

In Europe, people usually ate two meals a day: dinner at midday and a lighter supper in the evening. Smaller meals in between were common. But these were mostly for people who did not do manual labor. Church leaders and polite society did not like eating breakfast too early. Working men, young children, women, the elderly, and the sick still ate breakfast for practical reasons. Men often felt ashamed of eating breakfast because the church preached against overeating. Big dinner parties and late-night suppers with lots of alcohol were seen as wrong. These late meals were linked to gambling and rude talk. Snacks were common, even though the church did not like them. Working men often got money from their bosses to buy small snacks during breaks.

Table Manners

Medieval meals were usually shared by the whole household, including servants. Eating alone was seen as selfish. In the 13th century, Bishop Robert Grosseteste told the Countess of Lincoln to forbid private meals. He said it caused waste and dishonored the lord and lady. He also said servants should not take leftovers for their own parties. Instead, leftovers should be given to the poor.

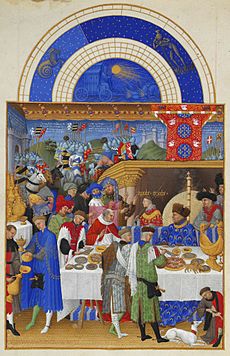

By the end of the Middle Ages, rich people started to eat in private rooms more often. Being invited to a lord's private room was a great honor. It was a way to reward friends and impress others. This allowed lords to eat more luxurious food while serving simpler food to the rest of the household in the great hall. However, at big events, the host and hostess usually ate in the great hall with everyone else. We know less about daily meals or the manners of common people. But they likely did not have many courses, fancy spices, or scented water for hand-washing.

For the wealthy, cleanliness was important. Before and between courses, guests were offered basins and towels to wash their hands. Women often ate privately or very little at feasts. This was because social rules made it hard for them to stay neat while eating. Fine dining was mostly for men. It was rare for guests to bring their wives or ladies-in-waiting. Social rank was shown through manners. Lower-ranked people helped higher-ranked ones. Younger people helped older ones. Men helped women to avoid them getting messy. Sharing drinking cups was common, except at the main table. Breaking bread and carving meat for others was also standard.

Food was served on plates or in pots. Diners took their share with spoons or bare hands. They put it on trenchers (stale bread slices), wood, or pewter plates. In poorer homes, people ate directly from the table. Knives were used, but most people brought their own. Only special guests got a personal knife. A knife was often shared with another guest. Forks were not widely used in Europe until much later. Even in Italy, forks only became common in the 14th century. When a Byzantine princess used a golden fork in the 11th century, it shocked people. Some even said her refined manners led to her body rotting away.

Cooking Food

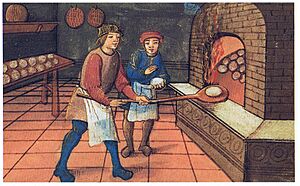

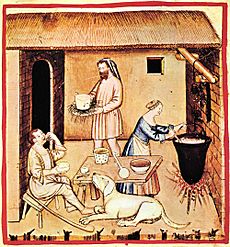

All cooking involved direct fire. Kitchen stoves did not exist until the 18th century. Cooks had to know how to cook over an open fire. Ovens were expensive and only found in large homes or bakeries. Communities often shared an oven for baking bread. There were also portable ovens that could be buried in hot coals. Larger wheeled ovens sold pies in the streets. But most people cooked in simple stewpots. This was the best way to use firewood and save cooking juices. So, stews were very common. Medieval dishes often had a lot of fat, if people could afford it. This was not a problem then, as people did hard work. Being plump was even seen as good. Only the poor, sick, or very religious were thin.

Fruits were often mixed with meat, fish, and eggs. A fish pie recipe from the 14th century included figs, raisins, apples, and pears with fish. It was important that dishes followed medical rules. Food had to be "tempered" by cooking it in the right way and mixing ingredients. Fish was seen as cold and moist. So, it was best fried or baked and seasoned with hot, dry spices. Beef was dry and hot, so it should be boiled. Pork was hot and moist, so it should be roasted. Some recipes even suggested replacing quince with cabbage or turnips with pears.

The fully edible pie crust appeared in recipes in the 15th century. Before that, the crust was just a container. Cookbooks from the Late Middle Ages show that cooking improved a lot. New techniques appeared, like clarifying jelly with egg whites. Recipes started to give detailed instructions.

Medieval Kitchens

In most homes, cooking happened on an open fireplace in the main living area. This made good use of heat. Even in rich homes, kitchens were often part of the dining hall for most of the Middle Ages. Later, a separate kitchen area started to appear. First, fireplaces moved to the walls. Then, a separate building or wing was built for the kitchen. This kept smoke, smells, and noise away from guests. It also reduced fire risk. Few medieval kitchens still exist because they were often temporary.

Many cooking tools we use today already existed. These included frying pans, pots, kettles, and waffle irons. But they were often too expensive for poor homes. Other tools for open-fire cooking included spits of different sizes. These could hold anything from small quails to whole oxen. There were also cranes with hooks to move pots away from the fire. Knives, stirring spoons, ladles, and graters were also used.

In rich homes, mortars and sieves were common. Many recipes called for food to be finely chopped, mashed, or strained. Doctors believed that finer food was absorbed better by the body. It also let skilled cooks shape food beautifully. Fine-textured food was a sign of wealth. For example, finely milled flour was expensive. Commoners' bread was usually dark and coarse. A common technique was "farcing." This meant skinning an animal, grinding its meat with spices, and putting it back into its own skin. Or, shaping it like a different animal.

Large noble or royal kitchens sometimes had hundreds of staff. These included bakers, butchers, carvers, and many helpers. A peasant home used firewood from nearby woods. But big kitchens needed to feed hundreds of people daily. A 1420 cookbook, Du fait de cuisine, suggests a chief cook should have at least 1,000 cartloads of dry firewood and a barn full of coal.

Food Preservation

Food preservation methods were similar to ancient times. They did not change much until the 19th century. The simplest method was drying food with heat or wind. This removed moisture and made food last longer. Drying stopped tiny organisms that cause decay. In warm places, food was dried in the sun. In colder areas, it was dried by strong winds (like for stockfish) or in warm ovens.

Chemical processes like smoking, salting, brining, and fermenting also made food last longer. These methods also added new flavors. Salting meat in autumn was common. This avoided feeding too many animals in winter. Butter was heavily salted (5–10%) to prevent spoiling. Vegetables, eggs, or fish were often pickled in jars with salt water and sour liquids like lemon juice or vinegar. Another method was cooking food in honey, sugar, or fat, then storing it in that. Grains and fruits were made into alcoholic drinks, which killed germs. Milk was fermented into cheese or buttermilk.

Professional Cooks

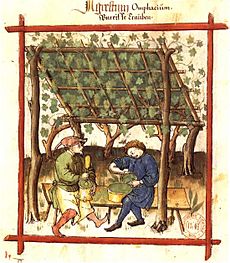

Most Europeans lived in the countryside and grew their own food. Large towns were different. They needed food from the surrounding areas. City people could find many food places. Many poor city dwellers lived in small places without kitchens. So, buying food from vendors was their only choice. Cookshops sold hot, ready-made food, like early fast food. Or, they cooked food that customers brought. Travelers, like pilgrims, used professional cooks to avoid carrying food. For richer people, there were specialists like cheesemongers, pie bakers, and wafer makers. Wealthy citizens could also hire cooks for big banquets.

City cookshops for workers were seen as bad places by the rich. Professional cooks often had a poor reputation. Geoffrey Chaucer's cook in Canterbury Tales was described as selling bad food. A French cardinal in the 13th century said cooked meat sellers were a health risk. While cooks were sometimes appreciated, they were often looked down upon. This was because they served basic body needs, not spiritual ones. The typical cook in stories was a hot-tempered man. He was often shown guarding his stewpot from thieves. In the 15th century, a monk named John Lydgate said, "Hot fire and smoke make many an angry cook."

Grains

Between 500 and 1300, European diets changed a lot. More farming meant a shift from meat and dairy to grains and vegetables. Before the 14th century, bread was less common for poorer people, especially in the north. A bread-based diet became more common in the 15th century. It replaced warm porridge or gruel meals. Leavened bread (with yeast) was common in wheat-growing areas in the south. Unleavened flatbread from barley, rye, or oats was more common in northern and highland regions. Flatbread was also common for soldiers.

The most common grains were rye, barley, buckwheat, millet, and oats. Rice was an expensive import for most of the Middle Ages. It was only grown in northern Italy later on. Wheat was common everywhere and seen as the most nutritious. But it was more prestigious and expensive. Fine white flour was only for the bread of the upper classes. As you went down the social ladder, bread became coarser, darker, and had more bran. During food shortages, cheaper substitutes were used. These included chestnuts, dried beans, acorns, and various plants.

Sops were common in medieval meals. These were pieces of bread soaked in wine, soup, or sauce. Another common dish was frumenty, a thick wheat porridge cooked in meat broth with spices. Porridges were made from all grains. They could be desserts or sick food if cooked in milk (or almond milk) and sweetened. Pies filled with meat, eggs, vegetables, or fruit were common. Turnovers, fritters, and doughnuts were also popular pastries. Grain, as bread crumbs or flour, was the most common thickener for soups and stews. By the Late Middle Ages, biscuits and wafers became high-status desserts.

Bakers were very important in medieval communities. Bread consumption was high in Western Europe by the 14th century. People ate about 1 to 1.5 kg of bread per day. Bakers were among the first town guilds. Laws controlled bread prices. The English Assize of Bread and Ale (1266) set tables for bread size, weight, and price based on grain prices. Bakers' profits were later increased to cover costs like firewood, salt, and even the baker's wife, house, and dog. Cheating with bread was a serious crime. Bakers who tampered with weights or added cheap ingredients faced harsh penalties. This led to the "baker's dozen." Bakers gave 13 loaves for the price of 12 to avoid being called a cheat.

Fruits and Vegetables

Fruits were popular and served fresh, dried, or preserved. They were often used in cooked dishes. Since honey and sugar were expensive, many dishes used fruits for sweetness. In the south, lemons, bitter oranges, pomegranates, quinces, and grapes were popular. Farther north, apples, pears, plums, and wild strawberries were more common. Figs and dates were eaten everywhere but were expensive imports in the north.

While grains were the main part of most meals, vegetables were common. Cabbages, chard, onions, garlic, and carrots were everyday foods. Peasants and workers ate many of these daily. They were less fancy than meat. Cookbooks from the late Middle Ages, meant for the wealthy, had few recipes using vegetables as the main ingredient. This does not mean nobles did not eat them. It means they were so basic they did not need to be written down. Carrots came in reddish-purple and less popular green-yellow types.

Legumes like chickpeas, fava beans, and field peas were common. They were important sources of protein, especially for poorer people. Doctors advising the upper class often viewed legumes with suspicion. This was partly because they caused gas. Also, they were linked to peasant food. Accounts from 16th-century Germany say many peasants ate sauerkraut three to four times a day.

Many common modern European ingredients were not available until after 1492. These include potatoes, kidney beans, cocoa, vanilla, tomatoes, chili peppers, and maize. Even then, it took a long time for these new foods to be accepted.

Dairy Products

Milk was an important source of protein for those who could not afford meat. It mostly came from cows, but goat and sheep milk were also common. Fresh milk was not usually drunk by adults, except for the poor or sick. It was mostly for very young or old people. Poor adults sometimes drank buttermilk or whey. Fresh milk was less common than other dairy products because it spoiled quickly. It was sometimes used in rich kitchens for stews. But almond milk was generally used instead.

Cheese was much more important, especially for common people. It might have been the main source of animal protein for the lower classes. Many cheeses we eat today, like Edam, Brie, and Parmesan, were known in the late Middle Ages. There were also whey cheeses, like ricotta. Cheese was used in pies and soups. Butter was popular in Northern Europe, where many cattle were raised. These areas included the Low Countries and Southern Scandinavia. While other regions used oil or lard, butter was the main cooking fat there. Butter production also led to profitable exports from the 12th century.

Meats

Wild game was popular for those who could get it. But most meat came from farm animals. Old working animals were slaughtered, but their meat was not very tasty. Beef was less common than today. Raising cattle needed a lot of land and feed. Oxen and cows were more valuable for work and milk. Lamb and mutton were common, especially where there was a lot of wool production. Veal was also eaten. Goat meat was consumed in some parts of medieval Europe.

Pork was much more common. Pigs needed less care and cheaper food. Pigs often roamed freely, even in towns. They could eat almost any organic waste. Suckling pig was a special treat. Almost every part of the pig was eaten, including ears, snout, tail, and tongue. Intestines and bladders were used for sausage casings. Sometimes, they were even used to make illusion foods like giant eggs. Some rare meats mentioned in recipes included hedgehog and porcupine. Rabbits were rare and highly prized. In England, they were introduced in the 13th century and carefully protected. In the south, domesticated rabbits were raised for meat and fur. It is often wrongly said that monks considered newborn rabbits as fish, allowing them to be eaten during Lent.

Many birds were eaten. These included pheasants, swans, peacocks, quails, partridges, storks, cranes, pigeons, and larks. Swans and peacocks were partly domesticated. But only the rich ate them. They were more for show at banquets than for their meat. Like today, ducks and geese were farm animals. But chickens were the most popular, like pigs. The barnacle goose was believed to grow from barnacles, not eggs. So, it was thought to be okay for fast days. But in 1215, Pope Innocent III banned eating barnacle geese during Lent. He said they lived and ate like ducks, so they were birds.

Meats were more expensive than plant foods, up to four times the price of bread. Fish was even more costly, up to 16 times as much. This meant that fasts could be very hard for those who could not afford meat alternatives. After the Black Death killed half of Europe's population, meat became more common for poorer people. Fewer people meant higher wages. Also, a lot of farmland was left empty. This allowed more land for animals, putting more meat on the market.

Fish and Seafood

Fish was less fancy than other meats. It was often just an alternative for fast days. But seafood was a main food for many people living near coasts. To medieval people, "fish" meant anything not a land animal. This included whales and porpoises. Beavers were also included because of their scaly tails and time in water. Barnacle geese were also sometimes called fish. These foods were allowed on fast days. However, the idea of barnacle geese as fish was not accepted by everyone. Emperor Frederick II checked barnacles and found no bird embryos.

Herring and cod fishing and trade were very important in the Atlantic and Baltic Sea. Herring was hugely important to the economy of Northern Europe. It was a main product traded by the Hanseatic League. Kippers (smoked herring) from the North Sea were sold as far away as Constantinople. Much fish was eaten fresh. But a lot was salted, dried, or smoked. Stockfish, which was dried cod, was very common. It needed to be beaten with a mallet and soaked in water before cooking.

Many shellfish like oysters, mussels, and scallops were eaten by people near coasts and rivers. Freshwater crayfish were a good alternative to meat on fish days. Fish was much more expensive than meat for people living inland, especially in Central Europe. So, it was not an option for most. Freshwater fish like eel, pike, carp, and salmon were common.

Drinks

Today, water is often drunk with meals. But in the Middle Ages, people worried about water purity. Doctors also recommended against it. So, alcoholic drinks were preferred. They were seen as more nutritious and good for digestion. Alcohol also kept them from spoiling. Wine was drunk daily in most of France and the Western Mediterranean. Further north, it was the drink of the wealthy. Peasants and workers there drank beer or ale.

Juices and wines from many fruits and berries were known since Roman times. These included pomegranate, mulberry, and blackberry wines. Perry (pear cider) and cider (apple cider) were popular in the north. Medieval drinks that still exist include prunellé (plum brandy) and mulberry gin. Many types of mead (honey drink) were in medieval recipes. Mead became less common at tables later on. It was mostly used as medicine. Mead was important for Slavic people at special events. It was a ceremonial gift for treaties and weddings. In medieval Poland, mead was as valuable as imported spices and wines. Kumis, fermented mare's or camel's milk, was known but mostly prescribed by doctors.

Plain milk was not drunk by adults, except the poor or sick. It was for the very young or old. They usually drank buttermilk or whey. Fresh milk was less common because it spoiled easily. Tea and coffee were popular in East Asia and the Muslim world during the Middle Ages. But they did not come to Europe until the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Wine

Wine was commonly drunk and seen as the best and healthiest choice. Doctors believed it was hot and dry, but watering it down made it more balanced. Unlike water or beer, wine was thought to help digestion, make good blood, and improve mood. Wine quality varied a lot. The first pressing of grapes made the best and most expensive wines for the rich. Second and third pressings were lower quality and had less alcohol. Common people usually drank cheap white or rosé wine from these later pressings. So, they could drink a lot of it. The poorest might drink watered-down vinegar.

Aging high-quality red wine needed special skills and expensive storage. This made it even more costly. Many medieval writings give advice on how to save wine that was going bad. This shows that spoilage was a common problem. A 14th-century cookbook, Le Viandier, describes ways to save spoiling wine. Spiced or mulled wine was popular with the rich. Doctors also thought it was very healthy. Wine was believed to carry food nutrients to the body. Adding fragrant spices made it even healthier. Spiced wines were made by mixing regular red wine with spices like ginger, cardamom, pepper, nutmeg, cloves, and sugar. These spices were put in small bags and steeped in the wine to make hypocras and claré. By the 14th century, pre-made spice mixes could be bought from merchants.

Beer

While wine was the main drink in much of Europe, it was not in northern regions where grapes did not grow. Rich people drank imported wine. But even nobles in these areas often drank beer or ale, especially later in the Middle Ages. In England, the Low Countries, northern Germany, Poland, and Scandinavia, beer was drunk daily by everyone. By the mid-15th century, barley, which is good for brewing, made up 27% of all grain fields in England.

However, medical ideas from Arab and Mediterranean cultures often disliked beer. For most medieval Europeans, beer was a simple drink compared to wine, lemons, and olive oil from the south. Even exotic things like camel milk got more positive attention in medical texts. Beer was just an acceptable alternative and was given negative qualities.

People thought beer's intoxicating effect lasted longer than wine's. But it did not cause the "false thirst" linked to wine. Though less common than in the north, beer was drunk in northern France and Italy. One French beer variant in a 14th-century cookbook was called godale (likely from English 'good ale'). It was made from barley and spelt, but without hops. In England, there were also poset ale (hot milk and cold ale) and brakot or braggot (spiced honey ale).

Hops could flavor beer and had been known since Carolingian times. But they were adopted slowly. Before hops, gruit, a mix of herbs, was used. Gruit also preserved beer, but less reliably. Another way to flavor was to increase alcohol content, but this was more expensive. Hops might have been widely used in England by the 10th century. They were grown in Austria by 1208 and Finland by 1249.

Before hops became popular, beer was hard to preserve. So, it was mostly drunk fresh. It was unfiltered and cloudy. It probably had less alcohol than modern beer. People in medieval Europe drank huge amounts of beer. Sailors in 16th-century England and Denmark got about 4.5 liters of beer per day. Polish peasants drank up to 3 liters of beer daily.

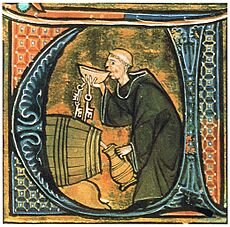

In the Early Middle Ages, beer was brewed mostly in monasteries and homes. By the High Middle Ages, breweries in German towns took over. Most were small family businesses. But regular production allowed for better equipment and new recipes. These breweries spread to the Netherlands in the 14th century, then to Flanders and Brabant, and reached England by the 15th century. Hopped beer became very popular in the late Middle Ages. In England and the Low Countries, people drank about 275 to 300 liters per year. They drank it with almost every meal: low-alcohol beers for breakfast, and stronger ones later. Hops made beer last six months or more, helping with exports. In late medieval England, "beer" meant hopped, and "ale" meant unhopped. Beer or ale was also called "strong" or "small." Small beer had less alcohol and was for children. As late as 1693, John Locke said small beer was the only drink suitable for children.

Brewing was less efficient by modern standards. But it could make strong alcohol if desired. A 1998 attempt to recreate medieval English "strong ale" made a very alcoholic brew (over 9% alcohol) with a pleasant, apple-like taste.

Distilled Drinks

Ancient Greeks and Romans knew about distillation. But it was not widely used in Europe until alembics were invented in the 9th century. Medieval scholars believed distillation made the "essence" of a liquid. They called all distillates aqua vitae ('water of life'). Early distillates, alcoholic or not, were used for cooking or medicine. Grape syrup with sugar and spices was used for illnesses. Rosewater was a perfume, cooking ingredient, and hand wash. Alcoholic distillates were also used to make fire-breathing show dishes. A piece of cotton soaked in spirits was put in the mouth of a cooked animal and lit.

Medieval doctors highly praised alcoholic aqua vitae. In 1309, Arnaldus of Villanova wrote that it "prolongs good health, gets rid of extra humours, reanimates the heart and maintains youth." In the Late Middle Ages, homemade spirits became more common, especially in German-speaking areas. By the 13th century, Hausbrand (literally 'home-burnt') was common, which was the start of brandy. By the end of the Late Middle Ages, spirits were so popular that sales and production limits appeared in the late 15th century. In 1496, Nuremberg limited aquavit sales on Sundays and holidays.

Herbs, Spices, and Condiments

Spices were among the most luxurious products. The most common were black pepper, cinnamon, cumin, nutmeg, ginger, and cloves. They all came from Asia and Africa, making them very expensive. This gave them high social status. Pepper was hoarded and traded like gold. About 1,000 tons of pepper and 1,000 tons of other common spices were imported into Western Europe each year in the late Middle Ages. This was worth enough grain to feed 1.5 million people for a year. Pepper was common, but saffron was the most exclusive. It was used for its bright yellow-red color and flavor. Yellow meant hot and dry, which were good qualities. Turmeric was a cheaper yellow substitute.

Some spices that are now rare include grains of paradise, which almost replaced pepper in French cooking. Also, long pepper, mace, spikenard, galangal, and cubeb. Sugar was considered a spice because it was expensive and had special health qualities. Few dishes used only one spice or herb. They usually combined several, like parsley and cloves, or pepper and ginger.

Common herbs like sage, mustard, and parsley were grown and used everywhere. Caraway, mint, dill, and fennel were also popular. Many of these plants grew across Europe or in gardens. They were a cheaper choice than exotic spices. Mustard was very popular with meat dishes. Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) called it "poor man's food." Local herbs were less fancy than spices. But they were still used in upper-class food, often for color. Anise flavored fish and chicken dishes. Its seeds were served as sugar-coated candies.

Medieval recipes often called for sour liquids. Wine, verjuice (juice of unripe grapes), vinegar, and tart fruit juices were common. They were a key part of late medieval cooking. With sweeteners and spices, they made a unique "pungent, fruity" flavor. Sweet almonds were also common. They balanced the sourness. Almonds were used whole, sliced, ground, and most importantly, as almond milk. Almond milk was probably the most common ingredient in late medieval cooking. It mixed spice and sour liquid aromas with a mild, creamy taste.

Salt was essential in medieval cooking. Salting and drying were the main ways to preserve food. This meant fish and meat were often very salty. Many recipes warned against too much salt. They suggested soaking foods to remove extra salt. Salt was present at fancy meals. The richer the host and the more important the guest, the fancier the salt container and the higher the quality of salt. Wealthy guests sat "above the salt." Others sat "below the salt." Salt cellars for the rich were made of precious metals and decorated. The diner's rank also decided how fine and white the salt was. Salt for cooking or for common people was coarser. Sea salt often had impurities and could be black or green. Expensive salt looked like the white salt we use today.

Sweets and Desserts

The word "dessert" comes from the Old French desservir, meaning 'to clear a table'. It started in the Middle Ages. Desserts usually included spiced sugar candies and mulled wine with aged cheese. By the Late Middle Ages, they also had fresh fruit with honey, sugar, or syrup, and boiled fruit pastes. Sugar was seen as much as a medicine as a sweetener. Its high cost made it a luxury. It appeared in fancy meals with meats, which seems strange to us today.

There were many kinds of fritters, crepes with sugar, sweet custards, and darioles. These were almond milk and eggs in a pastry shell. They could also have fruit, bone marrow, or fish. German-speaking areas liked krapfen: fried pastries with sweet and savory fillings. Marzipan was well-known in Italy and southern France by the 1340s. It is thought to be from Arab origins. English cookbooks have many recipes for sweet and savory custards, potages, sauces, and tarts with strawberries, cherries, apples, and plums. English chefs also liked using flower petals like roses and violets. An early form of quiche is in Forme of Cury, a 14th-century recipe book. It was a cheese and egg yolk tart.

Le Ménagier de Paris (1393) includes a quiche recipe with three cheeses, eggs, beet greens, spinach, fennel, and parsley. In northern France, many waffles and wafers were eaten with cheese and spiced wine. Candied ginger, coriander, aniseed, and other spices were called épices de chambre ('parlor spices'). They were eaten as digestives at the end of a meal to "close" the stomach.

Like in Spain, Arab conquerors in Sicily brought many new sweets and desserts to Europe. Sicily was famous for its candied fruits, nougat, and almond clusters. From the south, Arabs also brought ice cream making, which led to sorbet. They also brought sweet cakes and pastries. Cassata alla Siciliana was made from marzipan, sponge cake, and sweetened ricotta. Cannoli alla Siciliana were fried, chilled pastry tubes with a sweet cheese filling.

Cookbooks

Cookbooks, or recipe collections, from the Middle Ages are very important for understanding medieval food. The first cookbooks appeared in the late 13th century. These include Liber de Coquina and Tractatus de modo preparandi. While they describe real dishes, food experts do not think they were used like modern cookbooks. They were not step-by-step guides. Few people in a kitchen could read back then.

Recipes were often short and did not give exact amounts. Cooking times and temperatures were rarely given. This was because accurate clocks were not available. All cooking was done with fire. Professional cooks learned their trade by working as apprentices. A medieval cook in a large household could plan and make a meal without recipes. Surviving manuscripts are often in good condition. This suggests they were records for wealthy, educated household masters, like Le Ménagier de Paris from the late 14th century. Over 70 medieval recipe collections exist today in different European languages.

Housekeeping instructions, like those in Ménagier de Paris, also included details on how to oversee kitchen preparations. Later, in 1474, the Vatican librarian Bartolomeo Platina wrote De honesta voluptate et valetudine ("On honorable pleasure and health").

High-status exotic spices like ginger, pepper, cloves, sesame, and citron leaves appear in an 8th-century list of spices for a Carolingian cook. This list was written by Vinidarius.

Images for kids

-

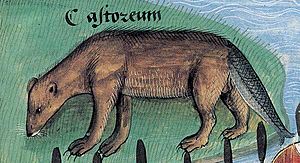

During the Middle Ages it was believed that beaver tails were of such a fish-like nature that they could be eaten on fast days; Livre des simples médecines, about 1480.

See also

In Spanish: Gastronomía de la Edad Media para niños

In Spanish: Gastronomía de la Edad Media para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |