Memphis sanitation strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Memphis sanitation strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

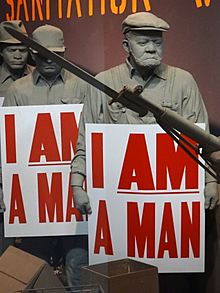

The strikers' slogan was "I AM a Man".

|

|||

| Date | February 12 – April 16, 1968 (2 months and 4 days) |

||

| Location |

Memphis, Tennessee, Charles Mason Temple, Clayborn Temple

|

||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

The Memphis sanitation strike was a major event in the Civil Rights Movement. It started on February 12, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee. Over 1,300 African American sanitation workers went on strike. They were protesting unfair treatment and dangerous working conditions.

The strike began after two workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, died in a garbage compactor. The workers demanded better pay, safer conditions, and recognition for their union. The strike lasted for over two months. It gained national attention and support from civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr..

Contents

Why the Strike Happened

Memphis had a long history of racial discrimination. Black residents faced unfair treatment in many parts of life. This included their jobs. Police often treated Black people violently. Laws known as Jim Crow laws kept Black people separate from white people.

Black workers were often paid much less than white workers. They were also kept out of unions. These unfair conditions continued for many years.

Workers' Conditions

Most sanitation workers in Memphis were Black. They had very low pay and few protections. Their supervisors, who were usually white, could fire them without warning. In 1968, sanitation workers earned about $1.60 an hour. This was not enough to live on. Many workers had to take other jobs or rely on welfare.

Their work was also very dangerous. They often worked unpaid overtime. They did not have proper uniforms or restrooms. There was no way for them to complain about unfair treatment.

Attempts to Form a Union

In the early 1960s, Black sanitation workers tried to form a union. They wanted better wages and working conditions. Their first attempt to strike in 1963 failed. Many workers were afraid to join a union. In 1963, 33 workers were fired just for going to a meeting.

In 1964, a union called Local 1733 of the AFSCME was successfully formed. It was led by T.O. Jones. However, city officials refused to officially recognize the union. Another strike attempt in 1966 was stopped by the city.

The Strike Begins

In late 1967, Henry Loeb became the mayor of Memphis. He had previously been in charge of the sanitation department. During his time there, he oversaw very tough working conditions.

On February 1, 1968, two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were killed. They were crushed to death in a garbage compactor. They had been sheltering from the rain inside the truck. This was not the first time workers had died this way. The city had refused to replace old, unsafe equipment.

This tragedy was the final straw for the workers. On February 11, over 400 workers met. They decided to go on strike. They wanted immediate action from the city.

First Days of the Strike

On February 12, 1968, most sanitation workers did not show up for work. Only a few garbage trucks were running. Mayor Loeb was very angry. He refused to meet with the striking workers.

The workers marched to the City Council chamber. They were met by many police officers. Mayor Loeb told them to go back to work. He even grabbed a microphone and shouted at them. The workers responded with laughter and boos. Loeb then stormed out of the room.

By February 15, huge piles of trash were building up in the city. Mayor Loeb started hiring new workers to replace the strikers. These new workers were white and had police escorts. The strikers did not welcome them. Sometimes, the strikers even attacked them.

Support for the Strikers

On February 18, Jerry Wurf, the national president of AFSCME, arrived in Memphis. He said the strike would only end when the workers' demands were met. The union leaders made a new list of demands. These included a 10% wage increase, fair promotion rules, sick leave, and union recognition.

Mayor Loeb continued to refuse. He said he would not let the union take money from the workers' wages. He believed he was protecting the workers from the union. But many Black leaders saw this as a way to control them, like during slavery. The workers felt they were grown men who could make their own choices.

By February 21, the workers had a daily routine. They would meet at noon and then march from Clayborn Temple to downtown. On February 22, they held a sit-in at city hall. They pushed the City Council to recognize their union. The mayor again said no.

On February 23, a large protest turned violent. Police used mace, tear gas, and billy clubs on the marchers. Reverend James Lawson spoke to the strikers. He said, "You are human beings. You are men. You deserve dignity." This message was shown on the famous "I Am a Man!" signs carried by the workers.

On February 26, over a thousand people gathered at Clayborn Temple. They raised money to support the movement. They also talked about fighting police brutality and improving housing and education for Black people in Memphis.

— "Sanitation Workers' Prayer" recited by Reverend Malcolm BlackburnOur Henry, who art in City Hall,

Hard-headed be thy name.

Thy kingdom C.O.M.E.

Our will be done,

In Memphis, as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our Dues Checkoff,

And forgive us our boycott,

As we forgive those who spray MACE against us.

And lead us not into shame,

But deliver us from LOEB!

For OURS is justice, jobs, and dignity,

Forever and ever. Amen. FREEDOM!

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Role

Many national civil rights leaders came to Memphis to support the workers. On March 18, Martin Luther King Jr. visited Memphis. He praised the large crowd of 25,000 people. He said, "You are demonstrating that we can stick together." King encouraged them to continue supporting the strike. He promised to return to lead a protest.

King returned to Memphis on April 3. He gave his famous "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech. In this speech, he spoke about seeing a "Promised Land" of equality.

"I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land! And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!"

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The very next day, April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. His death made the strike even more intense. Many feared riots would break out. Government officials urged Mayor Loeb to give in to the workers' demands. But Loeb still refused.

On April 8, a silent march was held in King's honor. Over 42,000 people participated. This included Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s wife.

The Strike Ends

The Memphis sanitation strike finally ended on April 16, 1968. The city agreed to recognize the union. They also agreed to increase wages for the sanitation workers. This was a big victory for the workers. It was also a key moment for Black activism and union activity in Memphis.

Legacy of the Strike

The Memphis sanitation strike is remembered as an important part of the Civil Rights Movement. It showed the power of unity and peaceful protest.

In 2017, the mayor of Memphis announced grants for the surviving 1968 sanitation strikers. This helped them financially. In 2018, the surviving strikers received the NAACP Vanguard Award. This honored their bravery and their fight for justice.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |