Pastoral pipes facts for kids

|

|

| Other names | Union pipes |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Playing range | |

| 2 octaves | |

| Related instruments | |

|

|

The pastoral pipe is a type of bagpipe that was played using bellows (a device that pumps air) instead of blowing into it with your mouth. It's known as the ancestor of the uilleann pipes that are played today.

These pipes were built in a similar way to modern uilleann pipes. They had a special part called a "foot joint" that helped play a very low note. The pastoral pipe could play a wide range of notes, covering two full octaves, including all the sharp and flat notes (a chromatic scale). In 1745, a book called "Pastoral or New Bagpipe" by J. Geoghegan was published in London. It taught people how to play this instrument. For a long time, people thought Geoghegan might have exaggerated what the pipes could do. But after studying some of the old pipes that still exist, experts found that the pastoral pipe really could play all the notes Geoghegan claimed!

Contents

What are Pastoral Pipes?

The pastoral pipe is a bellows-blown bagpipe, meaning air is pumped into it with bellows, not by the player's breath. It's considered the early version of today's uilleann pipes.

How are Pastoral Pipes Different?

The pastoral pipe had a special "foot joint" at the end of its main melody pipe (called the chanter). This joint allowed it to play one note lower than other pipes. It also had small holes on its sides, as well as the main hole at the bottom.

Pastoral pipes create a continuous sound, much like Highland pipes. Players change notes using quick finger movements called gracenotes. Unlike the later union pipes, you couldn't stop the sound by resting the chanter on your knee because of those side holes. However, many pastoral pipes were made with a foot joint that could be removed. If you took it off, you could then play them like union pipes. Most surviving pastoral pipes have two or three drone pipes (which play a continuous background note) and usually one "regulator" (a keyed pipe that can play chords).

History of the Pastoral Pipes

These bagpipes were popular in parts of Scotland (the Lowlands and Borders) and Ireland from the mid-1700s to the early 1900s. They were the early version of what we now call uilleann pipes. Many famous instrument makers created these pipes in cities like London, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Dublin, and Newcastle upon Tyne.

Where Did They Come From?

It's hard to say exactly which country the pastoral pipe and its later version, the union pipe, came from first. However, the earliest known book of tunes for these pipes, "Geoghegan's Compleat Tutor" from 1746, mentions a maker in London. As the pastoral pipe changed and improved between 1770 and 1830, it became the union pipe. Makers in Scotland, England, and Ireland all shared ideas and helped improve the design.

Who Played Them?

Both the pastoral pipes and union pipes were often played by wealthy gentlemen in Scotland, England, and by Anglo-Irish Protestants in Ireland. These were people who could afford to buy an expensive, handmade set of pipes.

The term "new bagpipe" was used because the instrument could play more notes and had been improved. The word "pastoral" might have come from the "ancient pastoral airs" (tunes) played on the instrument. These tunes were often gentle and sweet, like the music shepherds might play. This style fit the soft sound of the pastoral and union pipes in the late 1700s, when books, art, and music often celebrated country life. Some people think the pastoral bagpipe might have been invented by a skilled instrument maker who wanted to appeal to this popular "Romantic" style of music. The pastoral pipes, and later the union pipes, were definitely favorites of the upper classes in Scotland, Ireland, and North-East England. They were fashionable for a while at formal social events, which is possibly where the name "union pipes" came from.

Early Mentions of the Pipes

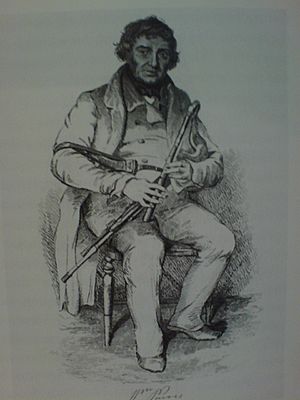

The first time we hear about a pastoral pipe is in popular plays of the time, like The Gentle Shepherd (1725) by Allan Ramsay and the English opera The Beggar’s Opera (1728). These plays used the pipes in their music. The Beggar’s Opera even had a big dance scene led by a pastoral pipe. This scene was drawn by William Hogarth (1697–1764), and his drawing clearly shows a bellows-blown bagpipe, similar to the one later shown in Geoghegan's teaching book.

The music in Geoghegan's book included songs by famous musicians like London organist John Ravenwood (1745) and composer John Grey (1745). It also featured music from William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius (1733) and arrangements from the Ossian cycle (a collection of epic poems). The pastoral pipes were seen as a classical instrument, played by gentlemen and popular among the upper levels of society. Joseph MacDonald noted in his 1760 book, "Complete Theory of the Great Highland bagpipe," that bellows pipes with a wider range were played across Scotland by that time.

The pipes were also mentioned in Ireland around 1760 by John O'Keefe, who said they were an instrument for polite society. The pastoral and early union pipes influenced folk music traditions in both Scotland and Ireland during the 1700s and 1800s. This shows a shared musical tradition that fit both formal concert music and the local music styles of Scotland and Ireland.

How Pastoral Pipes Are Tuned

It was once thought that pastoral pipes were hard to play notes in both the lower and upper ranges. However, recent studies and repairs of old instruments show this isn't true.

Playing Different Octaves

On modern uilleann pipes, players move from lower notes to higher notes by briefly stopping the chanter and increasing the air pressure in the bag. This makes the reed play a higher note. With pastoral pipes, you can get the same effect by increasing bag pressure while playing a quick gracenote. For example, to go from a low A to a high A, you can use an E gracenote. Old music written for pastoral pipes often has tunes that jump between these different ranges.

Being able to stop the chanter (which the union pipes could do) does help with playing. It also allows for more control over how loud or soft the music is, as the chanter can be lifted from or lowered to the knee to change the volume. This might have been a reason why the pastoral pipes changed into the union pipes, by removing the foot joint.

Pipe Design and Pitch

The pastoral pipe had a narrow opening (called a throat bore) of about 3.5–4 millimeters and an exit hole usually no bigger than 11 millimeters. Its design was very similar to the main melody pipes of later "flat set" union pipes made in the early 1700s. The reeds used were about 9.5–10.5 millimeters wide at the head.

These pipes were made to play in different musical keys, and a quiet sound with an E flat pitch was very common among the pipes that still exist today. Later versions sometimes had a sliding part on the foot joint. This allowed players to change the lowest note from a flat to a sharp when needed. Some sets even had a way to turn the drones on and off, with two regulators neatly placed at the top. A key was also added to the chanter to play more notes in the second octave.

The Chanter of the Pastoral Pipes

The chanter is the part of the pastoral pipe that plays the melody. It sounds similar to the chanters of later "flat set" union pipes.

How the Chanter Works

It has eight finger holes. When played with "open fingering" (meaning all holes are open or closed in a standard way), it can play notes like middle C, D, E, F♯, G, A, B, and C or C♯, D' in the first range of notes. Many other sharp or flat notes (accidentals) can be played by using "cross-fingering" (covering holes in a different pattern). A second range of notes can be played by increasing the air pressure in the bag. With the right reed, a few notes in the third octave can also be played. Later versions of these pipes had chanters that could play all the sharp and flat notes (fully chromatic), sometimes using as many as seven keys.

The chanter uses a complex reed with two blades, similar to those found in an oboe or bassoon. This reed must be made very carefully so it can play two full octaves accurately. Unlike an oboe or bassoon, the player can't use their lips to fine-tune the notes. Only the air pressure from the bag and the player's finger movements can be used to keep each note in tune.

Why the Foot Joint Was Removed

Over time, the pastoral pipes slowly changed into the union pipes. This happened as musical tastes changed, and people wanted instruments that could play with more expression.

Changes in Playing Style

The foot joint might have started to be used less as early as the 1740s to 1770s. Oboe players of that time, who often also played pastoral pipes, would frequently remove or turn the foot joint upside down. This allowed them to play the chanter by resting it on their knee, which was a different way of playing.

The change from an "open chanter" (like the pastoral pipe) to a "stopped chanter" (like the union pipe, which could be stopped on the knee) happened slowly. Pastoral pipes with removable foot joints were still being made until the 1850s and were played even after World War I. Eventually, the instrument was designed to be played on the knee rather than off it. Today, the small part at the bottom of a modern uilleann chanter is a leftover from where the foot joint used to be.

Makers of Pastoral and Union Pipes

Some of the oldest pipes that still exist today were made between the 1770s and 1790s. Famous makers include James Kenna from Mullingar, Hugh Robertson from Edinburgh, and later Robert Reid from North Shields.

How Makers Improved the Pipes

These pipe makers started to design the instrument so it would play best when rested on the knee. This allowed players to have more control over the sound. It's possible that for a while, there were two groups of players: union pipers who played without the foot joint, and old-style pastoral pipers who kept it and could play in both ways. Both "long" (with foot joint) and "short" (without foot joint) pastoral/union chanters were used in Scotland and Ireland until around World War One.

The development of the union and uilleann pipes (the term "uilleann" came about in 1904 from Irish nationalists) was also pushed by competition among makers. Throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s, pipe makers in Aberdeen, Dublin, Edinburgh, and Newcastle competed and copied each other's new ideas. It's now thought that the "regulators" (keyed pipes that play chords), which were already common on pastoral pipes, inspired the keyed Northumbrian smallpipes. These were likely first made by John Dunn, who made both pastoral and Northumbrian pipes in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Different Kinds of Pastoral Pipes

Old examples of pastoral pipes have been found in many different places, showing a wide range of designs. Several modern pipe makers have even tried to build new versions of these old pipes. They are not widely played today, but more and more people are becoming interested in them and researching their history.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |