Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 facts for kids

|

|

| Long title | An Act for the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the Poor in England. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 4 & 5 Will. 4. c. 76 |

| Territorial extent | England and Wales |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 14 August 1834 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repeals/revokes | Poor Act 1805 |

|

Status: Repealed

|

|

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 (often called the New Poor Law) was an important law passed by the British government. It completely changed how poor people were helped in England and Wales. Before this Act, local parishes gave money or food to the poor. This new law aimed to cut down on costs and change the system.

The Act was based on ideas that helping the poor too much would make them lazy. It suggested that people would rather claim help than work. So, the new law tried to make getting help less appealing. It wanted to make sure only those who truly had no other choice would ask for help.

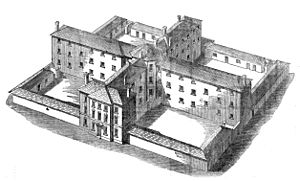

The main change was that poor people would only get help inside special buildings called workhouses. Conditions in these workhouses were made very tough. This was to discourage anyone who wasn't truly desperate from entering. The law passed easily in Parliament, but it caused a lot of anger and social unrest, especially in the industrial North of England.

Over time, the importance of this law faded. In 1948, it was officially cancelled by a new law that set up a modern welfare state system.

Contents

Why the Poor Law Changed

Before 1834, the old system of helping the poor was becoming very expensive. Especially in the farming areas of Southern England, it was common for poor workers to get extra money from the parish. This was known as the Speenhamland System.

In 1832, the government set up a special group called the Royal Commission to study the problem. This group found that the old system was badly managed and cost too much.

Key Ideas for the New Law

The Commission's ideas for the new law were based on two main principles:

- Less Eligibility: This meant that life inside a workhouse should be worse than the life of the poorest worker outside. The idea was to make workhouses so unpleasant that people would only go there if they had absolutely no other choice.

- Workhouse Test: This meant that the only way to get help was to go into a workhouse. No more money or food would be given to people in their own homes.

The Commission suggested big changes:

- Help given outside the workhouse (called "out-relief") should stop. Help should only be given inside workhouses. The conditions there would be so strict that only truly needy people would accept it.

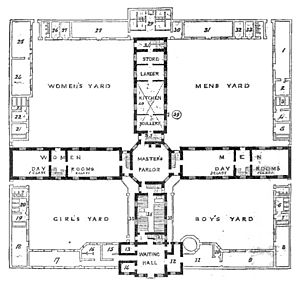

- Different groups of poor people should be kept separate. For example, men, women, and children would live in different parts of the workhouse. This even meant separating husbands and wives.

- A central group should be in charge to make sure all workhouses followed the same rules. This was to prevent different areas from treating poor people differently.

- Mothers of children born outside of marriage would get much less support. The law would no longer try to find the fathers to make them pay for child support.

Ideas Behind the Poor Law

The Poor Law Amendment Act was built on several important ideas from that time.

Population Growth and Poverty

One idea came from Thomas Malthus. He believed that the number of people would grow faster than the amount of food available. This would naturally lead to poverty. Malthus thought that giving help to the poor would only make them have more children. This would then lead to even more poverty later on. So, he argued against giving too much help.

Wages and Aid

Another idea was the "iron law of wages" by David Ricardo. This idea suggested that if poor workers received extra money from the parish, it would cause employers to pay lower wages to everyone. This meant that the old system was actually hurting workers who didn't get aid. It also made taxpayers pay more to support low-wage employers.

Greatest Good for Most People

Edwin Chadwick, a key person in creating the new law, was influenced by Jeremy Bentham's idea of utilitarianism. This idea says that the best action is one that brings the "greatest happiness for the greatest number of people." Chadwick believed that if workhouses were strict, fewer people would claim help. This would save money for taxpayers, which was seen as a "greater good."

Bentham also thought that people would always choose what was pleasant. So, to make people work, getting help had to be made unpleasant. This was why workhouses were designed to be harsh.

Rules of the New Poor Law Act

The Act itself didn't list all the detailed rules for workhouses. Instead, it created a special group called the Poor Law Commission. This group had the power to make the rules.

- The Poor Law Commission was made up of three men. They worked in Somerset House in London.

- Local areas still elected their own "Boards of Poor Law Guardians." These boards managed the local workhouses and paid for them.

- However, the Poor Law Commission could tell these local boards what to do. This meant local people had less say in how the poor were helped.

- The Commission could order parishes to join together to form "Poor Law Unions." These unions were large enough to build and run a workhouse.

- The Commission could also decide how many staff workhouses needed and what their salaries should be.

- They could order the "classification" of people in workhouses. This meant separating men, women, and children.

- They also had the power to decide when and how "out-door relief" (help outside the workhouse) could be given.

The Act gave the Commission huge power over how help was given to the poor across England and Wales. They could make rules for managing the poor, running workhouses, educating children in them, and even for training poor children as apprentices.

However, the Commission could not interfere in individual cases. They could only make general rules. These general rules had to be shown to the government and Parliament.

The Act also set penalties for anyone who didn't follow the Commission's rules. But it didn't have a way to punish areas that didn't set up a Board of Guardians.

The Act did give some rights to poor people. For example, people with mental illness could not be kept in a workhouse for more than two weeks. Also, workhouse residents could not be forced to attend religious services that were not their own. Children could not be taught a religion their parents objected to.

Putting the New Law into Action

The Poor Law Commission started putting the new system in place. They began in the Southern counties first, where the problems were biggest. At first, the cost of helping the poor went down, which was seen as a success.

However, there were also terrible stories of poor people being treated badly or refused help. Some poor people were encouraged to move from the countryside to Northern towns to find work. People in the North worried that the new law was just a way to lower wages.

By 1837, when the new system reached the factory towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire, the economy was struggling. Usually, during tough times, factory workers would work fewer hours and get less pay. They would then get "out-door relief" to make ends meet. But the new law wanted to stop "out-door relief."

Even though the Poor Law Commission said they wouldn't stop out-door relief in these factory areas, people didn't believe them. Many towns fought against the new rules, and some even had riots. Eventually, the resistance was overcome. But "out-door relief" was never fully stopped in many Northern areas.

Challenges with the Poor Law Act

The Poor Law Amendment Act faced many problems.

- One goal was to move jobless rural workers to cities where there was work. Another goal was to protect city taxpayers from paying too much for the poor. It was hard to do both at the same time.

- The idea of "less eligibility" made people look for work in towns. But old laws about where people could live (Settlement Laws) made it hard to move. These laws were also expensive to enforce.

- Building new workhouses and joining parishes into unions took a long time.

- "Out-door relief" continued even after the new law was introduced. The Commission had to issue more rules about it.

The Act was put into practice differently across England and Wales. This was a problem with the old law too. Different areas had different levels of wealth and unemployment. Local Boards of Guardians also interpreted the law in their own ways. This led to a very uneven system.

Poor working-class people, including farm workers and factory workers, strongly disliked the new law. They said the food in workhouses was not enough to keep workers healthy. The newspaper The Times even called it "the starvation act." The law also forced families to separate when they entered workhouses, which caused great distress.

Fighting Against the Poor Law

There was strong anger and organized opposition to the new Poor Law. Workers, politicians, and religious leaders all spoke out against it. This eventually led to some of the harshest parts of the workhouse system being changed.

A big scandal happened at the Andover workhouse. Conditions there were found to be cruel and dangerous. This led to a government investigation. The report criticized the Poor Law Commission heavily. Because of this, the government replaced the Poor Law Commission with a new "Poor Law Board." This new board was watched much more closely by the government and Parliament.

The famous writer Charles Dickens strongly criticized the Poor Law in his novel Oliver Twist. He described the tiny portions of food in Oliver's workhouse. He also made fun of the rule that separated married couples. Dickens showed how children in workhouses were denied exercise and forced to do useless tasks.

In the North of England, people strongly resisted the new law. They felt their old system was working well. They argued that because unemployment went up and down, new workhouses would be empty most of the time. This would be a waste of money. However, the protests eventually died down. In some cases, the protests were so successful that parts of the Act were changed, making the protests less needed.

What Was the Impact?

A study from 2019 looked at the effects of the 1834 Poor Law reform. It found that the reform did not change wages in the countryside. It also didn't affect how easily workers could move to new jobs or the birth rate among the poor. The study suggested that the suffering caused by the law didn't really help landowners or raise wages for the poor. It also didn't help people move to better jobs in cities. So, this big reform, meant to improve the economy, actually had little effect on economic growth in Industrial Revolution England.

See also

Images for kids