Ring of Stones facts for kids

The Ring of Stones, also known as the Circle of Stones, is a mysterious arrangement of stones. Some people believe it might have been built by survivors from the Vergulde Draak, a Dutch ship that was wrecked in 1656. The ship went down about 100 kilometers (62 miles) north of where Perth, Western Australia, is today.

The Ring of Stones was first reported in 1875 by a surveyor named Alfred Burt and his friend Harry Ogbourne. They saw it on the coast of Western Australia. However, they didn't make an official report about it at the time. It wasn't until 1930 that Burt told the Western Australia Police about his discovery. He said the Ring of Stones was on the central west coast, between Woodada Well and the ocean, about half a mile (0.8 km) from the shore.

Contents

Alfred Burt's Discovery

Alfred Earl Burt was an important person in Western Australia. His father was the first Chief Justice. Alfred himself became the Registrar of Titles and Deeds.

On November 3, 1930, Burt wrote to the police commissioner. He wanted to report what he had found way back in 1875.

I was working for the Admiralty Marine Survey as a Draftsman in 1875. I was camped at a well called ‘Woodada’ on the old coast road from Geraldton to Perth.

One day, I needed to go to the coast, about nine miles away. I had to take supplies to Captain Archdeacon, who was camped there, and get instructions. I started with Mr Harry Ogbourne and a pack horse. When we got close to the ocean, we found a very thick bush area. As we cut our way through, we found a clear spot about 14 feet (4.3 meters) square. All around it was thick bush, and in the middle was a complete circle of stones.

Burt drew a simple map with his letter. He showed that the Ring of Stones was 4 feet (1.2 meters) wide. It was in a circular clearing that was 14 feet (4.3 meters) wide. Burt wanted to go back and look more closely, but Captain Archdeacon wouldn't let him. Before he died, Ogbourne said there were no other stones nearby. This made it seem like the Ring of Stones was not natural. It looked like it was made by people.

Burt told the police about the stones because he had just learned about the lost Dutch ship, the Vergulde Draak. This ship had sunk on April 28, 1656, off the coast of Western Australia. A journalist named Dircksey Cowan had told him about it. The Vergulde Draak was carrying a lot of money, 78,600 guilders, which sank with the ship. This money was not found until the wreck was located in 1963. Burt thought the Circle of Stones might mark the spot of a "Treasure Trove" from the Vergulde Draak. This was likely why he told the police.

The Search for Treasure

The police commissioner didn't do anything right away. But in early 1931, two boys, Fred and Alister Edwards, found 40 old coins. These coins were from 1618 to 1655, including Spanish reales. They found them in sand dunes north of Seabird. This discovery caused a lot of excitement. People started guessing that the coins were from the Vergulde Draak and its treasure.

Because of this, the police started a search for the Ring of Stones in May 1931. Constable Sam Loxton from Dongara led the trip. Alfred Burt, a local landowner named Mr. A. R. Downes, and another local, Mr. Parker, joined him. From May 8 to 11, they tried to find the Ring of Stones in the area Burt had described. However, this part of the coast has very thick scrub, rocky ground, and steep sand ridges. Burt said that in some places, the scrub was so thick "even a bullock could not penetrate it." The search failed.

People wondered if Burt remembered the location correctly. But in the end, they decided to try again after burning the area. This would make it easier to move around and search. So, another search happened in late February 1932.

The 1932 search was again led by Constable Loxton and included Downes, but not Burt. Local Aboriginal people, the Yuat, had burned the land before the search began. Some Yuat people also guided the group and burned more areas that the earlier fires had missed. For almost a week, the group walked up and down the coast and through the bush. Again, they found nothing. Loxton noted that the sand dunes "increase in size so quickly." He thought it was "quite possible that the Spot may have been covered up years ago."

More Treasure Hunts

The police didn't seem to do anything more after the second search. But in July 1932, a farmer named Fred King wrote to Constable Loxton. King told him about a line of stones that were "placed in a straight line running east and West for about one mile." These stones were about 150 yards (137 meters) apart. They pointed to a large sandhill on the coast and to Woodada Well on the east end, about 3 miles (4.8 km) from the sea. King noted that these stones were "hidden by thick scrub." Although King's letter was mentioned in a newspaper report about the Vergulde Draak treasure, nothing came of it.

In March 1933, Constable Loxton filed another report. A Mr. Stokes, who was sick in the hospital, claimed he had been with Burt and Ogbourne when they found the Ring of Stones in 1875. Things stayed quiet until a well-known author and bushman, J. E. Hammond, decided to try and find the Ring of Stones. Hammond was a friend of Alfred Burt's. It seems that in 1937, Hammond searched for two weeks. He even burned "several hundred acres of scrub" but didn't find anything. He concluded that the Ring had been covered by moving sand.

Talk about the Vergulde Draak treasure started again in March 1938. It was reported that more old coins had been found by children from the Baramba Assisted School. This was in the same area where the Edwards boys had found coins earlier. However, this seemed to be just a retelling of the 1931 find.

Then, in December 1938, Jack Hayes and Gabriel Penney found a Ring of Stones. They believed it was Burt's Ring of Stones. Their discovery was reported in The West Australian newspaper on February 10, 1939.

It seems Penney, who hunted wild horses, had seen a stone arrangement around 1931. But he hadn't looked into it further at the time. In December 1938, he told Hayes, who ran the Dongara Hotel, about it. The two men went to find the spot again. They drove their truck to within "about nine miles" (14.4 km) of the Ring. Then they walked the rest of the way. The "thorny bush" made it hard to move, but Penney led Hayes to the exact spot. Hayes described it:

There were three groups of stones in a cleared area ... One was in the form of a ring. The other two were rectangular in shape, located on each side of the circle. One of the rectangular areas had a base line of about 22 yards (20 meters) long, with sides about three feet (0.9 meters) long.

They took photos, but they weren't very clear. The photos showed the Ring and part of one of the lines of stones sticking out.

Hayes said the "whole formation was arranged in such a manner as to act as a pointer." The Ring was "at least two miles" (3.2 km) from the coast. But they didn't give more exact location details. They dug for the treasure, but only found limestone rock "under not more than two inches (5 cm) of sand." There were some potholes about six to nine inches (15-23 cm) deep. And so, the treasure hunt stopped there.

New Expeditions and Discoveries

In his 1994 book, And Their Ghosts May Be Heard, Rupert Gerritsen wondered about the Ring of Stones. He thought it might have been built by the lost sailors from the Vergulde Draak. Perhaps it was a way to show searchers that they were heading inland, in a northeast direction. This was suggested by the longer arm of the line of stones.

Other ideas for the Ring of Stones were considered. For example, it could be an Aboriginal stone arrangement or a marker for a cattle route. But neither of these seemed likely. The oldest cattle route went through areas with more water, about 15 km (9.3 miles) inland. Also, Aboriginal stone arrangements are rare in southern Western Australia. None seem to match the shape Hayes described. They are also not usually found in such difficult and out-of-the-way places. A recent idea linking the Ring of Stones to a supposed Aboriginal site, the Eneabba Stone Arrangement, is not supported by facts.

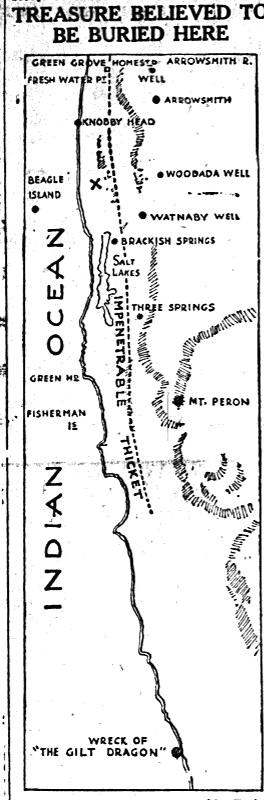

To find out more about the Ring of Stones, Gerritsen worked with Bob Sheppard. Sheppard is a researcher and runs Warrigal Press. They did a lot of research and looked for the site in person. They used newspaper reports and information from Malcolm Uren's book, Sailormen’s Ghosts. Gerritsen, Sheppard, and others went on a first trip to find the Ring of Stones in April 2004. They focused on an area based on a map from The Mirror in 1933. They also used the path Burt took in 1875 and the limited location details from Hayes and Penney.

The search area was hard to reach. It had coastal scrub and heath covering steep old sand dunes. They used two 4-wheel drive vehicles. However, the thick scrub caused problems. The vehicles' tires kept getting punctured. Before the day was over, the group had to go back to the small coastal town of Leeman. Every tire, including the spares, was flat or going flat.

Because of this experience, Gerritsen decided that the only way to search was on foot. He was about to start another trip in October 2008. But then, Sheppard found Burt's original letter, his simple map, and police reports. These were in the State Records Office of Western Australia. From these papers, it was clear that Burt's Ring of Stones was very different. It had a different shape, location, and size than the Ring of Stones found by Hayes and Penney. They realized that two different "Ring of Stones" had been reported!

With the documents from the police archives, including Burt's map, Gerritsen based his search on the distance from the coast Burt had given. He also used the Ring of Stones' position shown on the map. As a result, he found what seemed to be the site of Burt's Ring of Stone in just one day, on October 28, 2008. The next day, he confirmed this location. He did this by following the last part of the route Burt had taken from Woodada Well, as shown on his map.

However, while the location matched Burt's description, in the center of the clearing was a pile of stones. It was 2.1 meters (6.9 feet) long, 1.0 meter (3.3 feet) wide, and 20 cm (7.9 inches) high. It looked like a grave. Gerritsen took photos and GPS readings. He also used a metal detector to search the area. When he returned to Perth, he told Sheppard. Sheppard visited the site a few days later. He confirmed that the location seemed correct and that the pile of stones did look like a grave.

Continuing the Search

After this, attention turned to finding Hayes and Penney's Ring of Stones. Burt's Ring of Stones was "half a mile" (0.8 km) from the coast. It was 4 feet (1.2 meters) wide and a simple circle. But the Hayes-Penney Ring of Stones was "about" or "at least two miles" (3.2 km) from the coast. It was "eight feet" (2.4 meters) across and had a line of stones leading off it, making it look "like a pointer."

Besides the distance from the coast, there wasn't much specific location information in Hayes and Penney's story. It seemed they drove south from Dongara to the end of a dirt track. This was within "about nine miles" (14.4 km) of their Ring of Stones. Then they walked for "seven or eight miles" (11.2 - 12.8 km).

Based on the limited and sometimes unclear information from Hayes, and using maps from the time Hayes and Penney found their stones, people tried to figure out their journey. This placed the Hayes-Penney's Ring of Stones about 25 km (15.5 miles) south-southeast of Dongara. It was also about 30 km (18.6 miles) north of Burt's Ring of Stones.

To rule out other possibilities, Gerritsen also started looking into Aboriginal stone arrangements on this part of the coast. He checked the Western Australian Department of Indigenous Affairs Aboriginal Heritage Inquiry System. Specifically, he looked at sites called Eneabba Stone Arrangement (Site No. 4760) and Eneabba West (Site No. 15297). However, the Eneabba Stone Arrangement could not be found in its described location, even after a thorough search. When Gerritsen looked at the Eneabba West site, it clearly did not look like the Ring of Stones at all.

However, Gerritsen did find the remains of what looked like a man-made stone wall near the Eneabba West site on June 17, 2009. This wall overlooked a shallow valley. The structure is in a hard-to-reach and difficult place. It looks like it could have been a lookout or a defensive structure. Even after careful checking, digging test pits, and using metal detectors twice in 2009, no signs of human activity or presence were found. People are still thinking about what this structure might be. It could be an Aboriginal stone arrangement, or it could have been built by survivors from the Vergulde Draeck, runaway convicts, drovers, campers, or even people doing military exercises in the area.

The search for the Hayes-Penney Ring of Stone began in June 2009. A search area of 6.4 square kilometers (2.5 square miles) was marked out. The boundaries were based on trying to recreate Hayes and Penney's journey. They also used the location details in their story and the uncertainties that came with them. The search was also guided by the published photographs. These photos gave visual clues about the type of land where they found the Ring of Stones.

By July 2010, the search of the marked area was finished, but they found nothing. Gerritsen then contacted the archives of West Australian Newspapers in July 2010. He wanted to see if they still had the letter Hayes wrote to Uren in February 1939. He also hoped to find the "rough sketch of the locality" and at least one extra photo that Uren had said came with the original letter. This search was not successful.

So, the search for the Hayes-Penney Ring of Stones is still going on. Since the beginning of July 2010, other search methods have been used. These are based on different ideas about where the Ring of Stones might be and new ways of recreating Hayes and Penney's journey.