Sébastien Rale facts for kids

Sébastien Rale (also spelled Racle, Râle, Rasle, and Rasles) was a French Jesuit missionary. He lived from January 20, 1657, to August 23, 1724. Rale worked with the Abenaki people in North America. He encouraged them to stand up against British settlers in the early 1700s. This led to a conflict known as Dummer's War (1722–1725). Rale was killed by New England soldiers during this war. He also created an Abenaki-French dictionary while living in North America.

Contents

Early Life and Missions

Sébastien Rale was born in Pontarlier, France. He studied in Dijon. In 1675, he joined the Society of Jesus, a group of Catholic priests. He taught Greek and public speaking in Nîmes. In 1689, Rale volunteered to work as a missionary in the Americas. He traveled there with Louis de Buade de Frontenac, who was the Governor General of New France.

Rale's first mission was in an Abenaki village called Saint Francois, near Quebec City. After that, he spent two years with the Illiniwek Indians in Kaskaskia.

Queen Anne's War and Suspicions

In 1694, Rale was sent to lead the Abenaki mission at Norridgewock, Maine. This village was located on the Kennebec River. He built a church there in 1698. The New England colonists were worried about a French missionary living among the Abenaki. They thought he would encourage the tribe to be hostile towards them.

Queen Anne's War was a conflict between New France and New England. Both sides wanted to control the region. In 1703, Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley met with tribal leaders. He asked them to stay neutral in the war. However, some Norridgewock warriors joined French and Indian forces. They attacked Wells, Maine. The New England colonists believed Father Rale was making the tribe fight against them.

Governor Dudley even offered a reward for Rale's capture. In the winter of 1705, 275 New England soldiers tried to seize Rale. But Rale was warned and escaped into the woods. The soldiers then burned the village and the church. The French tried to make the local Native Americans distrust the British. This happened even though the Abenaki needed British trading posts for supplies.

The Treaty of Utrecht and Land Disputes

The Peace of Utrecht treaty ended the conflicts in North America in 1713. After this, the Native Americans swore loyalty to the British Crown at the Treaty of Portsmouth. However, it is likely the Native Americans did not fully understand what the treaty meant. The border between New France and New England was still unclear. The British claimed land all the way to the St. George River. But most Abenaki living there supported the French and the Catholic Church.

In 1717, Governor Samuel Shute met with Abenaki leaders in Georgetown, Maine. He warned them that working with the French would lead to their "utter ruin." Wiwurna, an Abenaki leader, complained about colonists building settlements and forts on their land. He said the land belonged to his people. Governor Shute insisted the colonists had the right to expand. New England settlers kept moving onto the Kennebec River. The Wabanakis responded by taking their livestock.

The Governor-General of New France, Vaudreuil, wrote in 1720 that Father Rale "continues to incite Indians... not to allow the English to spread over their lands." Governor Shute demanded that Rale be removed from Norridgewock. In July 1721, the Wabanakis refused. They also demanded that hostages, who were given during earlier talks, be released.

Chief Taxous died, and Wissememet became the new chief. Wissememet wanted peace with the colonists. He offered beaver furs to make up for past damages. He also offered four hostages to promise no future harm. But Rale kept encouraging some people in the tribe to fight. He said that any treaty with the governor was "null and void" if he did not approve it.

Rale asked Vaudreuil for more help. About 250 Abenaki warriors from Quebec arrived at Norridgewock. They were very hostile to the colonists. On July 28, 1721, over 250 Native Americans arrived in Georgetown. They were in war paint and flying French flags from 90 canoes. Rale and Pierre de la Chasse, a mission superior, were with them. They delivered a letter demanding that the colonists leave. The letter said Rale and his people would kill them and burn their homes and animals if they did not. The colonists stopped selling gunpowder, ammunition, and food to the Abenaki.

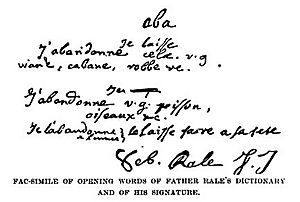

In January 1722, 300 soldiers led by Colonel Thomas Westbrook surrounded Norridgewock to capture Rale. Most of the tribe was away hunting. Rale was warned and escaped into the forest. However, his strongbox was found. It had a secret compartment with letters. These letters showed he was working for the French government. They also promised the Native Americans enough ammunition to drive the colonists away. His three-volume Abenaki-French dictionary was also found. It was later given to Harvard College.

Sébastien Rale and the Abenaki People

Rale had one of the longest and most important periods as a priest in this part of the New World. He focused on his mission work. He learned the Abenaki language to be a better priest. He also studied the Algonquin language. He even ran a mission in Illinois for a few years. In 1694, Father Rale was sent to the Kennebec mission in old Acadia. This was the westernmost mission in the area. Father Rale was the first permanent pastor in lower Kennebec.

Father Rale cared deeply for the Abenaki people. He wrote a long poem to his brother, saying, "My throat is white and it bleeds" and "I shook the chapel bell in tears/ And cried revenge!" He said this during the war, taking the side of the tribe against the settlers. Many French people and Jesuit priests at that time thought the Abenaki were wild and needed to be "civilized." But Rale did not think this way. He became a martyr for the Abenaki. He died while helping them fight against settlers taking their lands.

The Jesuit mission in Abenaki territory had been there since 1632, long before Rale arrived. The French created the mission around the time they took control of Quebec. Rale was put in charge of keeping the Abenaki from moving around. He wanted them to live a more settled life centered on Christianity. Many people in St. Lawrence looked to the Abenaki land for help with the fur trade.

The Abenaki people's land was very important to settlers because of the fur trade. Before Rale came to Norridgewock, the native people there had signed a treaty. This treaty made them British subjects, but they likely did not understand what this meant. This made the French seek out Father Rale and his Abenaki group for supplies needed for the fur trade.

The New England settlers said the native people in Norridgewock had verbally declared their loyalty to the British. But Father Rale denied this. He kept his loyalty to the French. Throughout his life, Rale remained a beloved priest to the people of the area. Many Abenaki still see him as a martyr. They believe he gave his life to help them resist the settlers.

At the start of the French and Indian War, the colonists asked the Abenaki to stay neutral. But because of their religious ties with the French, they could not fight against them. Father Rale was at the meeting for the native people. He said the Abenaki would be "ready to take up the hatchet against the English whenever he gave them the order."

Father Rale's War

After the raid on Norridgewock, the Abenaki tribe attacked. On June 13, 1722, they burned Fort George at the mouth of the Kennebec River. They took hostages, most of whom were later released. They wanted to exchange them for those held in Boston. Governor Shute then declared war on the eastern Native Americans on July 25. But he suddenly left for London on January 1, 1723. He was frustrated with the government assembly, which controlled money for the war. Lieutenant-governor William Dummer took over. More Abenaki attacks convinced the assembly to act. This conflict became known as Dummer's War.

The Battle of Norridgewock

In August 1724, 208 New England soldiers left Fort Richmond. They traveled up the Kennebec River in 17 whaleboats. They split into two groups, led by Captains Johnson Harmon and Jeremiah Moulton. At Taconic Falls, 40 men stayed to guard the boats. The rest continued on foot. On August 23, 1724, the soldiers reached the village of Norridgewock.

Father Rale was sent to North America with fur traders and fishermen. He was believed to be the reason the Abenaki planned to help the French against the British. This started in 1721 when Rale demanded the New Englanders return their Abenaki hostages. In response, the British stopped trading gunpowder and other supplies to the Abenaki. Then, in 1722, Colonel Thomas Westbrook raided Father Rale's mission to capture him. Rale escaped, but the soldiers found letters suggesting he worked for the French government.

To get revenge for this raid, the Abenaki burned Brunswick. Father Rale said, "they took care to not harm the settlers, but to destroy their property." Later, in August 1724, New England soldiers, along with Mohawk Native Americans, destroyed Norridgewock. They killed at least 100 Abenaki people and Father Rale himself.

Rale's scalp and the scalps of others killed were taken to Boston. Boston had offered a reward for the scalps of hostile Native Americans. Harmon was promoted. Two stories of Rale's death then appeared. The French and Native Americans said he died as a "martyr." They claimed he stood at the foot of a large cross, drawing soldiers' attention to himself to save his people. The New England soldiers said he was a "bloody incendiary" shot in a cabin while reloading his musket.

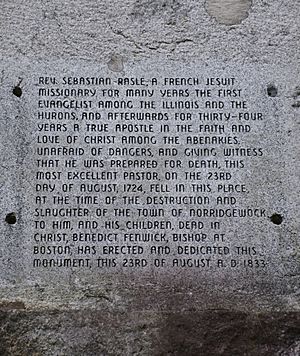

The 150 Abenaki survivors returned to bury the dead. Then they left Norridgewock for Canada. Rale was buried under an altar in the settlement. In 1833, Bishop Benedict Joseph Fenwick dedicated an 11-foot tall monument. It was built over Rale's grave in St. Sebastian's Cemetery in Madison, Maine.

Rale remains a figure about whom people have different opinions. Some historians, like W. J. Eccles, say that since 1945, some Canadian historians have changed their view of New France's history. They believe earlier views were biased against Catholic, French, and American Indian elements. However, this is a general view and does not change the specific details of Rale's life and actions.

Images for kids