Siege of Limerick (1650–1651) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Limerick 1651 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland | |||||||

Henry Ireton. The English Parliamentarian commander who besieged Limerick in 1651 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hugh O'Neill | Henry Ireton (died of disease) Hardress Waller |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 | 8,000 soldiers 28 siege guns 4 mortars |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 700 soldiers killed 5,000 civilians killed |

2,000 killed | ||||||

Limerick is a city in western Ireland. It was the site of two important battles called sieges during the Irish Confederate Wars. The second and biggest siege happened between 1650 and 1651. This was part of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, when English forces took control of Ireland.

Limerick was one of the last cities still held by Irish groups called Irish Confederates and their allies, the Royalists. They were fighting against the English Parliament's army. The city's defenders were led by Hugh Dubh O'Neill. They eventually surrendered to Henry Ireton, a leader of the English Parliament's army, after a long and difficult siege. Over 2,000 English soldiers died during the siege. Henry Ireton, who was Oliver Cromwell's son-in-law, also died from a disease.

Contents

First Attempt: Ireton's Siege in 1650

By 1650, the Irish Confederates and their English Royalist friends had been pushed out of eastern Ireland. This happened because of Oliver Cromwell's army. They tried to defend a line along the River Shannon, and Limerick was a strong fort at the southern end of this line.

Oliver Cromwell left Ireland in May 1650. He put Henry Ireton in charge of the English Parliament's forces. Ireton sent Hardress Waller to try and capture Limerick. The city was defended by Hugh Dubh O'Neill and his experienced Ulster army. When Waller's first soldiers arrived, the city leaders also let James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven and his Royalist troops join the defense.

On September 9, 1650, Waller asked the city to surrender. Ireton joined him later. However, the weather became very wet and cold. Ireton had to give up the siege before winter arrived. He took his army back to Kilkenny for the winter.

Second Siege: Ireton Returns in 1651

Ireton came back the next year, on June 3, 1651. He had a much larger army of 8,000 men. He also brought 28 large cannons and 4 mortars for attacking the city walls. He again asked Hugh Dubh O'Neill to surrender Limerick, but O'Neill refused. The siege began.

Limerick's Strong Defenses

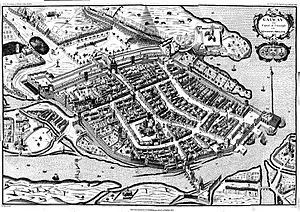

In 1651, Limerick was divided into two parts: the English town and the Irish town. The Abbey River separated them.

- The English town, which had King John’s Castle, was surrounded by water. The Abbey River was on three sides, and the River Shannon was on the other. This area was known as King's Island.

- There was only one bridge to the island, called Thomond bridge. It was protected by strong earth walls.

- The Irish town was more open, but it was also very well fortified. Its old medieval walls had been made stronger with about 6 meters (20 feet) of earth. This made it very hard to break through them.

- The Irish town also had many strong points called bastions along its walls. These bastions had cannons that could fire at anyone trying to get close. The biggest bastions were at St John’s Gate and Mungret Gate.

- The city's army had 2,000 soldiers. Most of them were experienced fighters from the Confederate Ulster army. They had fought well in the siege of Clonmel the year before.

How Ireton Attacked

Because Limerick was so strong, Ireton did not try to attack the walls directly. Instead, he tried to cut off the city's supplies. He also built earthworks for his cannons to bombard the defenders.

- His troops captured the fort at Thomond bridge. But the Irish defenders destroyed the bridge itself. This stopped the English army from reaching the English town by land.

- Ireton then tried to attack the city by water. A group of soldiers tried to storm the city in small boats. They had some success at first. But O’Neill’s men fought back hard and pushed them away.

- After this attack failed, Ireton decided to starve the city into surrendering. He built two forts nearby, called Ireton’s fort and Cromwell’s fort, on Singland Hill.

- The Irish tried to send help to the city from the south. But this attempt was defeated at the Battle of Knocknaclashy.

- O’Neill's only hope was to hold out until bad weather and hunger forced Ireton to leave. To save supplies, O’Neill tried to send the city's old people, women, and children out. However, Ireton’s soldiers killed 40 of these civilians and sent the rest back into Limerick.

Surrender and Aftermath

After this, O’Neill was pressured by the city's mayor and people to surrender. The soldiers and civilians in the city suffered terribly from hunger and a serious outbreak of plague. Also, Ireton found a weak spot in the Irish town's defenses. He managed to break through the wall, which meant a full attack could happen at any moment.

Finally, in October 1651, four months after the siege began, some of Limerick’s soldiers (English Royalists led by Colonel Fennell) rebelled. They turned some cannons towards O’Neill’s men. They threatened to fire unless O'Neill surrendered. Hugh Dubh O’Neill surrendered Limerick on October 27.

The people living in Limerick were allowed to keep their lives and property. But they were warned that they might be forced to leave in the future. The soldiers were allowed to march to Galway, another city still fighting. However, they had to leave their weapons behind.

Some leaders of Limerick, both civilian and military, were not given these easy terms. A Catholic Bishop named Terence Albert O'Brien, an Alderman, and the English Royalist officer Colonel Fennell were executed. O’Neill was also sentenced to death. But he was saved by another English commander, Edmund Ludlow, and instead imprisoned in London. The former mayor, Dominic Fanning, was also executed, and his head was placed above St. John's Gate as a warning.

The Cost of the Siege

Over 2,000 English Parliament soldiers died at Limerick. Most of them died from disease, not from fighting. Henry Ireton, the English commander, died about a month after the city fell. About 700 Irish soldiers died. An unknown, but likely much larger, number of civilians also died. It is often estimated that about 5,000 civilians died during the siege.

|